.219 Donaldson Wasp

A Benchrest Classic

other By: Stan Trzoniec | June, 25

Even while I was in the Empire State in the mid-1950s, the .219 Donaldson was already almost 20 years in development and most of it right out of Fultonville, New York. Reference material clearly shows that Harvey A. Donaldson had begun experimenting with high-speed, efficient small-capacity cartridges as early as 1935. He began with the .22 Niedner Magnum but theorized a much better .22-caliber varmint cartridge could be designed. This was Donaldson’s forte – he dedicated his whole life to the development of better, more efficient rifle ammunition.

The baseline for the .22 Niedner was the .25 Remington rimless case. Not completely satisfied, he later turned to the .219 Winchester Zipper. With a slightly larger capacity in concert with his specially designed Donaldson case that incorporated a more abrupt shoulder angle, he started to gain ground. Mind you, Donaldson was a very astute man when it came to cartridges.

According to Landis in his detailed account of the .219 Donaldson Wasp in his book Twenty-Two Caliber Varmint Rifles, to simply “alter a case by increasing its capacity to hold powder, without increasing the ability of that case to burn more powder, in no way constitutes an improvement.” He also goes on to say that Donaldson wanted to produce “a small, convenient, high intensity cartridge of great accuracy, economy and a very flat trajectory without going to the realm of long, heavy cases which often gave high erosion and, at times, considerable pressures at the head.” Furthermore, and again I quote from the book, “. . . the .219 Wasp design was worked out by Donaldson with the idea of having both bullet weight and powder charge so balanced that a case full of powder could be used without exceeding safe pressures or without having it fail to reach adequate burning pressures.” Donaldson surely had his act together, and the end result was the .219 Donaldson Wasp.

One day while checking out ads in a varmint magazine, I noticed a company called Bullberry Barrel Works (2430 W 350 N, Hurricane UT 84737) was chambering rifles in the .219 Donaldson. Talking to the folks out there, I realized this was a full-service operation. They not only rebarrel or rechamber rifles for over 100 different cartridges from the .17 Cooper to .50-caliber black powder, but they also offer a complete in-house gunsmithing service. Sights, muzzle brakes and stock work from bare bones to complete wood are listed in its catalog.

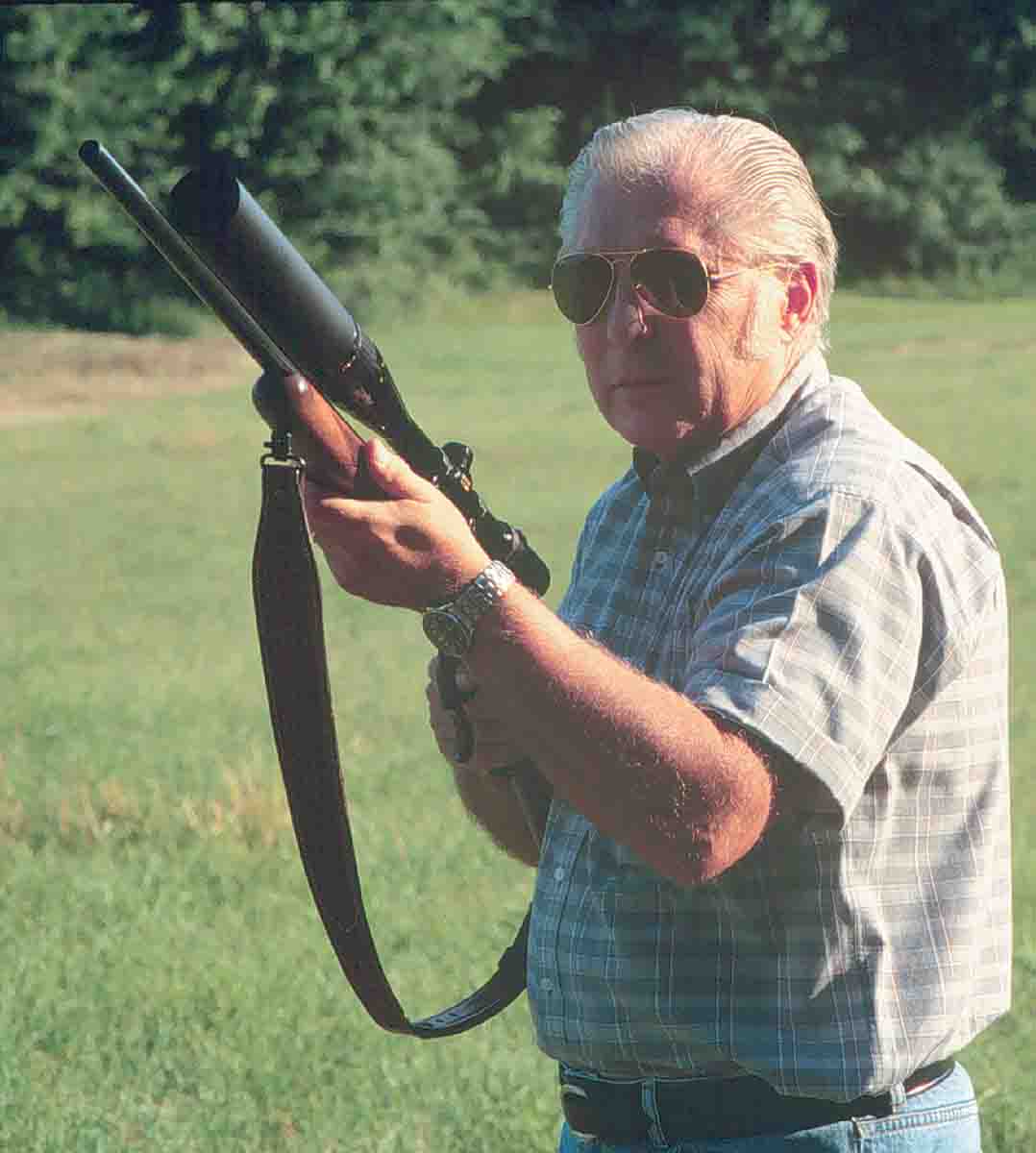

Because of its rimmed case, my choice for a rifle was the Ruger No. 1, and out it went to Bullberry. While it was there, die sets were ordered from RCBS, .30-30 Winchester brass from Winchester and a Bausch & Lomb 6-24x scope, complete with an extra extension that provides about 8 inches of lens hood on the front of the scope, which was taken from my personal stockpile.

Shooting the .219 Donaldson is the easy part. Getting to that stage is not hard, but it is time consuming as cases must be formed from readily available .30-30 Winchester brass. Prior experience shows that after all the preparations, set up, adjusting and die placement on the press, figure on doing at least 150 to 200 cases at a time to maximize both time and effort at the bench. For what it’s worth, do one step at a time, attack each part when you are fresh and go at it when you can assure yourself of complete concentration.

The first case-forming die pushes the shoulder back while still retaining the .30-caliber neck. It’s best to roll about a dozen cases on the lube pad, being careful to keep the lube off the shoulder. This prevents excess lube from forming case dents in and around the shoulder area, and while you can “blow” them out on the initial firing, it still is unsightly and, in my opinion, only starts the progression to weaken the case where the wrinkles or dents occur. After case lubing, I take every fifth or sixth case and place a minute amount of lube on the neck to ease the transition down the body of the host case. This not only keeps dents to a minimum – I only had two out of 200 cases – but also makes case forming a whole lot easier.

The next step is die number two. Here the parent .30-30 Winchester case neck is reduced from a .325 inch outside diameter (OD) to .290 inch OD. The shoulder will also start to show a more distinct profile.

The trim die is the last in this series of case forming. The first run-through reduces the neck to .255 inch OD with about a .227 inch inside diameter. Then the cases are trimmed. Using a common hobbyist or mini-hacksaw, trim the neck even with this trim die. Since this die is hardened, no harm will come to it. Finish off with a pass or two of the file, chamfer the neck for smoothness and run it through the full-length die to even the case out all around.

When using the full-length die for the first time, it’s a good idea to watch the die’s progression on the case. There is no need to push the neck or shoulder back any more than necessary, so I set this die to contact the shellholder or a little less. After running one or two cases through this die, check for chambering in the rifle. Depending upon the die set, you might need to adjust slightly, especially if the case is rather tight in the chamber. This will be the final step in achieving a snug fit to hold the bullet and establish proper parameters and specifications.

Check the cases for overall length and trim to end up with a case that is no longer than 1.765 to 1.70 inches before firing. One point here: If you check the Hornady Handbook 4th Edition reloading manual, you’ll note that while the case drawing shows a proper 1.750 inches as the maximum overall length, the written specifications show a maximum of 1.813 inches and a minimum of 1.800 inches. This was obviously not caught by the proofreader.

To make sure I was on the right track, CCI 200 primers were seated in 20 cases with 28.0 grains of H-4895 and capped off with 55-grain bullets. For the first run, the Speer 55-grain FMJ boat-tail seated to 2.20 inches did just fine with 10 shots running about one inch.

Upon arriving home with 20 fireformed cases, work started in earnest toward a uniform program of setting up the full-length die set to neck size only. Smoking the necks of a few cases, the die was adjusted so it sized the neck only while just coming to bear on the shoulder in a very imperceptible manner. To verify everything was okay, these few cases were cleaned, checked for length and chambered in the Ruger No. 1. Without fail they slipped into the recut chamber, and the action closed without a hitch.

Mussing over past hunts and the areas I frequent for ’chucks and crows, I settled on bullet weights in the 50- to 55-grain range. Velocities hopefully would be anywhere from 3,400 to 3,600 fps with most bullets, if the combination of powders and primers ran true. Most brands of bullets were represented, including a sample of the blue bullet (VLC) by Barnes, now discontinued.

Propellants were yet another hard decision, but research showed the Wasp seemed to be at its best with powders in the medium to medium-slow range. This would follow in the steps from the fastest Hodgdon H-4198 to medium-slow propellants like H-380. For a break-in charge to complete the fireforming operation, I used 29.5 grains of H-380 with CCI 200 Large Rifle primers. The choice here of H-380 was a wise one – filling 180 cases with a spherical powder makes life much easier!

After fireforming it was back to the bench to neck size only followed by a check for overall length. As expected, the cases did grow a little and were trimmed, deburred and chamfered both inside and out. Research continued into powder considerations by venturing into some older material by Landis, Page, Lyman and even by ol’ Donaldson himself.

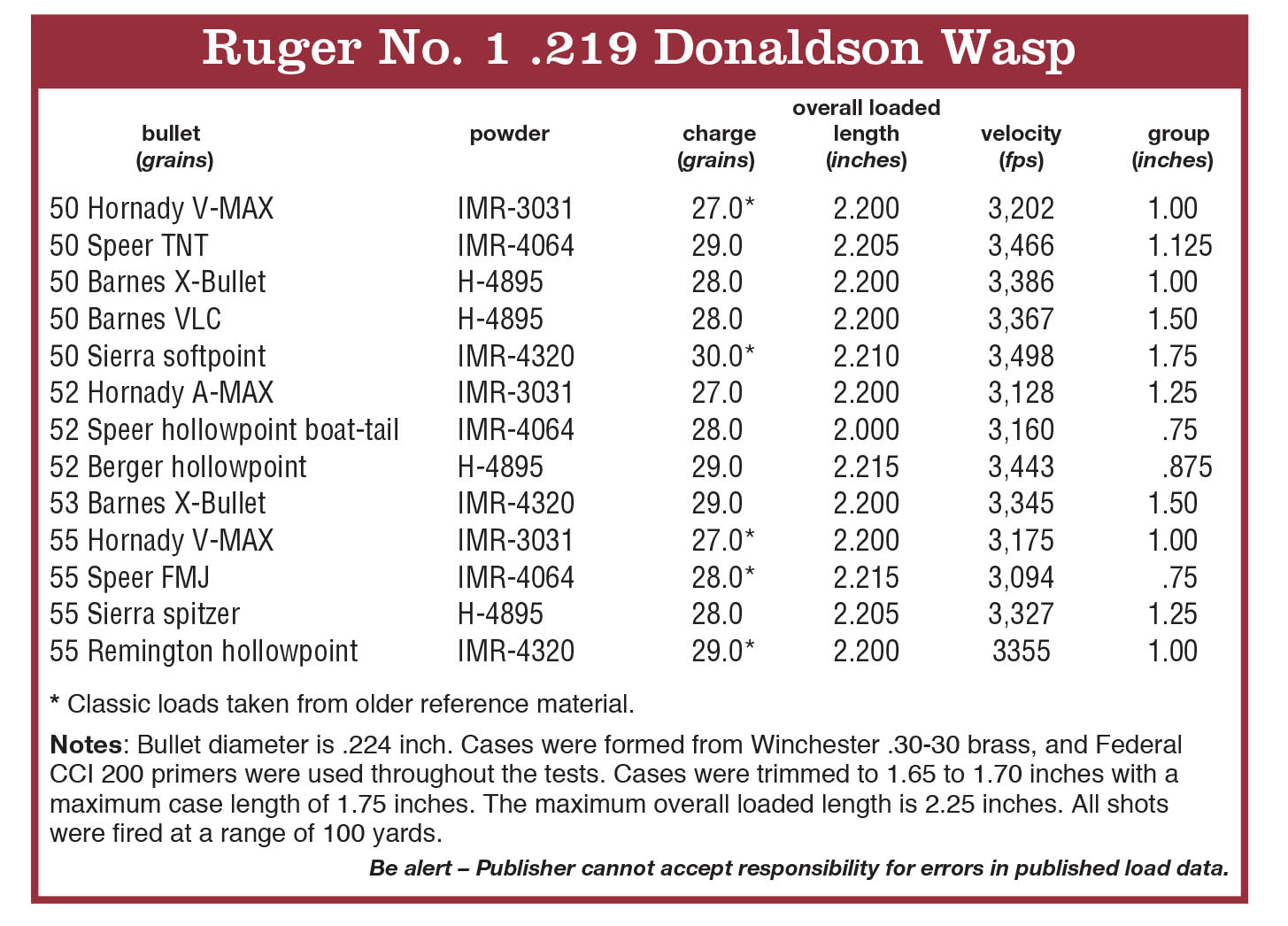

It’s amazing the way some things remain a constant. For instance, Donaldson, Warren Page, Lyman in its 39th Edition and Hornady in its recent loading manual all agree on 27.0 grains of IMR-3031 for a 50-grain bullet. However, using a 55-grain pill with the same IMR-3031, we see 27.0 grains (Donaldson), 26.0 grains (Page), 26.0 grains (Lyman) and 27.3 for the new version of the Hornady book. All are very close considering a near 50-year span in time. [Check current manuals for updated information. – Ed.]

Further investigation showed four powders seemed to stick out in the crowd. I found a trio of favorites: IMR-3031, IMR-4064 and IMR-4320. One of the newer suitors, H-4895, seems to find favor in both the

Hornady and Hodgdon loading manuals as one that also reaches favorable velocities. For primers I turned to CCI 200 Large Rifle primers and, considering the capacity of the newly formed Wasp case and powders it utilizes, nothing more powerful is needed. For the real accuracy sticklers out there, you might want to try CCI BR-2 primers.

In the final analysis, and if we really look close at this grand, old cartridge, it might have been overrated in years past to get the edge on the velocity race, especially when it came to barrel length. For instance, in the Hornady manual its test rifle has a barrel length of 29 inches. Hodgdon uses a 28-inch barrel, and I’m sure Harvey Donaldson never used a short barrel (or if he did I’d like to know, as barrel length is never mentioned in my reference material or his writings). So when it came to my testing, velocity readings from the Ruger were lower than expected on the first go-round. In subsequent testing I used two chronographs back to back just to verify these readings.

With a 50-grain bullet, Hornady reached 3,600 fps with 27.0 grains of IMR-3031, but I could only squeak out 3,202 fps. Using the same load with a 52-grain A-MAX, Hornady lists 3,500 fps; my 26-inch barrel generated 3,128 fps. Ditto on the 55-grain bullet: Hornady shows 3,500 fps with the classic load of 27.0 grains of IMR-3031; I made it to 3,175 fps. With Hodgdon, 28.0 grains of IMR-4895 hit 3,501 fps in its test barrel; my readings show 3,327 fps.

Landis quotes velocities of over 3,700 fps with 29.0 grains of IMR-3031. Usually two full grains of pro- pellant will give an increase somewhere in the neighborhood of 200 to 300 fps; here two more grains (according to Landis) boosted the velocity readings almost 600 fps! The only thing I can figure is that early chronographs were primitive at best (measuring bullet impact on steel plates, for instance) and again, a very long or target barrel was used.

My loads for the most part are right up there with the masters of the 1930s and 1940s. They are classic and safe and, to be fair, there are some that do approach 3,500 fps, but accuracy did suffer. Still another interesting angle of the velocity story relates to regular bullets and the VLC (Varmint Lubricated Coating) bullets by Barnes. Its 50-grain uncoated bullet actually beat the blue bullet by just about 20 fps and with better accuracy. No big thing, but with the controversy surrounding the merits of coated bullets, sometimes interesting things pop up that add to the sum of the whole equation.

If you’re looking for the best all-around powder, I’d pick IMR-4320; the best modern propellant, H-4895.

The best loads in the Ruger .219 Donaldson were those that fell below some of the maximum loads published. This is not earth shattering in itself and is usually the case with most cartridges. Two of the best loads under an inch – the 52- and 55-grain Speer bullets – were a little below maximum with velocities in the 3,000- to 3,200-fps range. The next best load would be my choice for an all-around ’chuck or varmint load in my area: a Berger 52-grain hollowpoint with 29.0 grains of H-4895 for a mean velocity of 3,443 fps. Groups ran under an inch, which is fine with me; velocity was the third best of the day.

In its heyday, the .219 Donaldson was a great cartridge and still is even by modern standards. For the most part the .219 seemed to gather its followers in the benchrest cir-cuit with a scattering of devotees using the same rifle in the field in order to capture both the velocity and accuracy advantages of the cartridge. This could be the reason I remember those sports using “heavy-barreled” guns in New York state.

Increasing powder charges could be the answer in some instances by a half or even a full grain, but I think in the long run the .219 Donaldson got beat out fair and square by the likes of the .222, .223 and the .22-250 Remingtons. To place yet another nail in the coffin, forming brass for the .219 Donaldson is labor intensive – something only true, dyed-in-the-wool fans (like me) would even think about doing.

So after 40 odd years of waiting, was the .219 Donaldson really worth it? To that question I have to answer yes. It was an itch I really had to scratch, something I wanted to work with and shoot if only for old-time’s sake. Nostalgia is a weakness of mine, and the .219 Donaldson falls right in. Am I going to continue to fine tune the loads even more? You bet. In the end, who knows, maybe a day in the future will find me over the state border on a chuckin’ foray just outside the village of Fultonville, shooting in the shadow of old Harvey Donaldson.