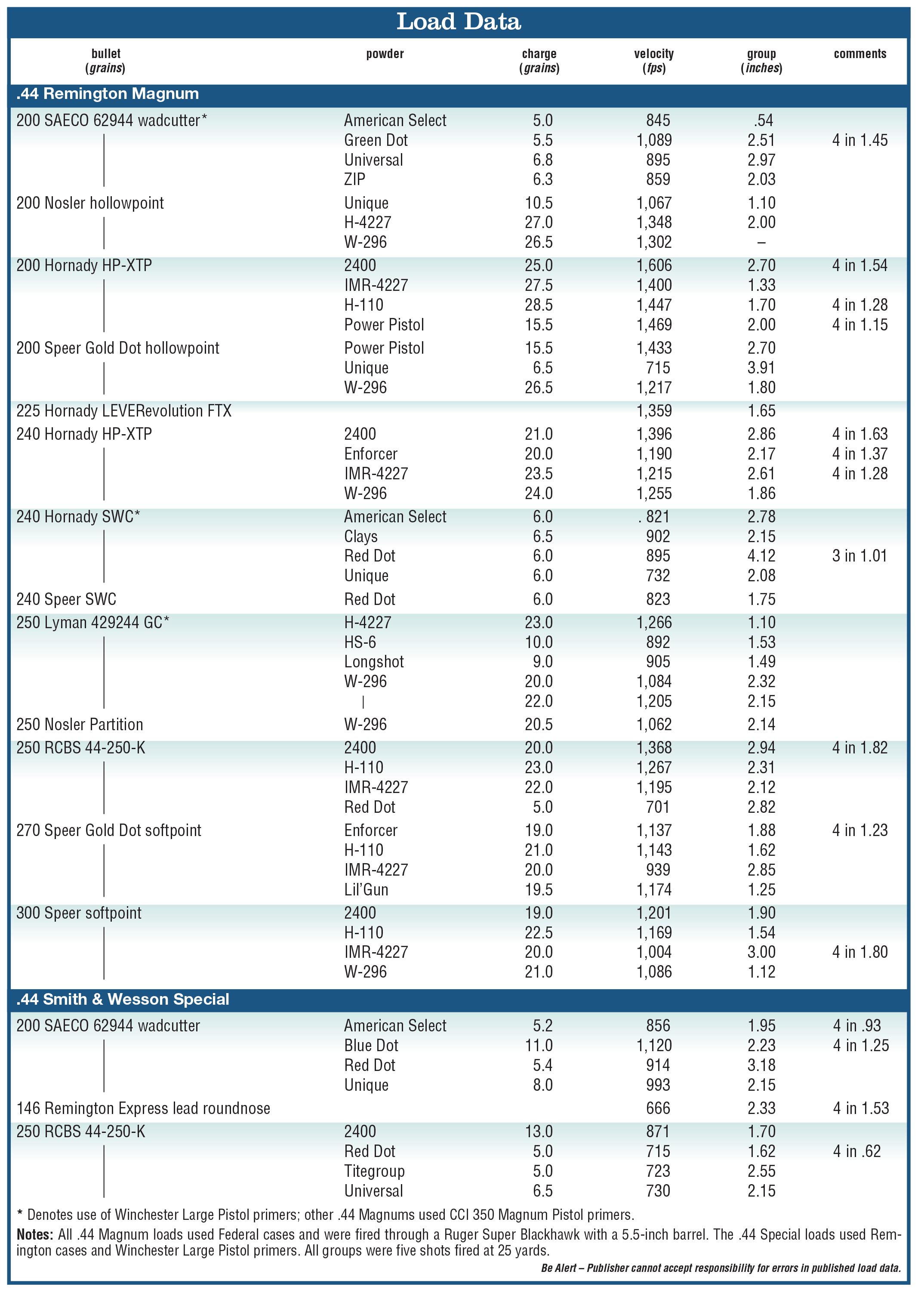

.44 Magnum

A Versatile Revolver Cartridge

other By: John Haviland | February, 26

Light and heavy and old and new loads make the .44 Remington Magnum an exceedingly flexible handgun cartridge for plinking and hunting.

I seem to have a Remington .44 Magnum revolver at hand every time I head to the shooting range or hunting field – for good reason too. By selecting different weights and styles of bullets and juggling powder charges, the .44 Magnum is an easy recoiling plinking and target gun, a hard hitter for big game or the last thing a marauding bear will ever see.

Short History

If you’ve read any of Elmer Keith’s writings, you know how he started in 1925 developing high-pressure .44 S&W Special loads that shot 250-grain bullets at

1,200 fps. You also know how he browbeat the Smith & Wesson and Remington people until they brought out a .44 Magnum revolver and ammunition in 1956. Keith never received a dime from all his work.

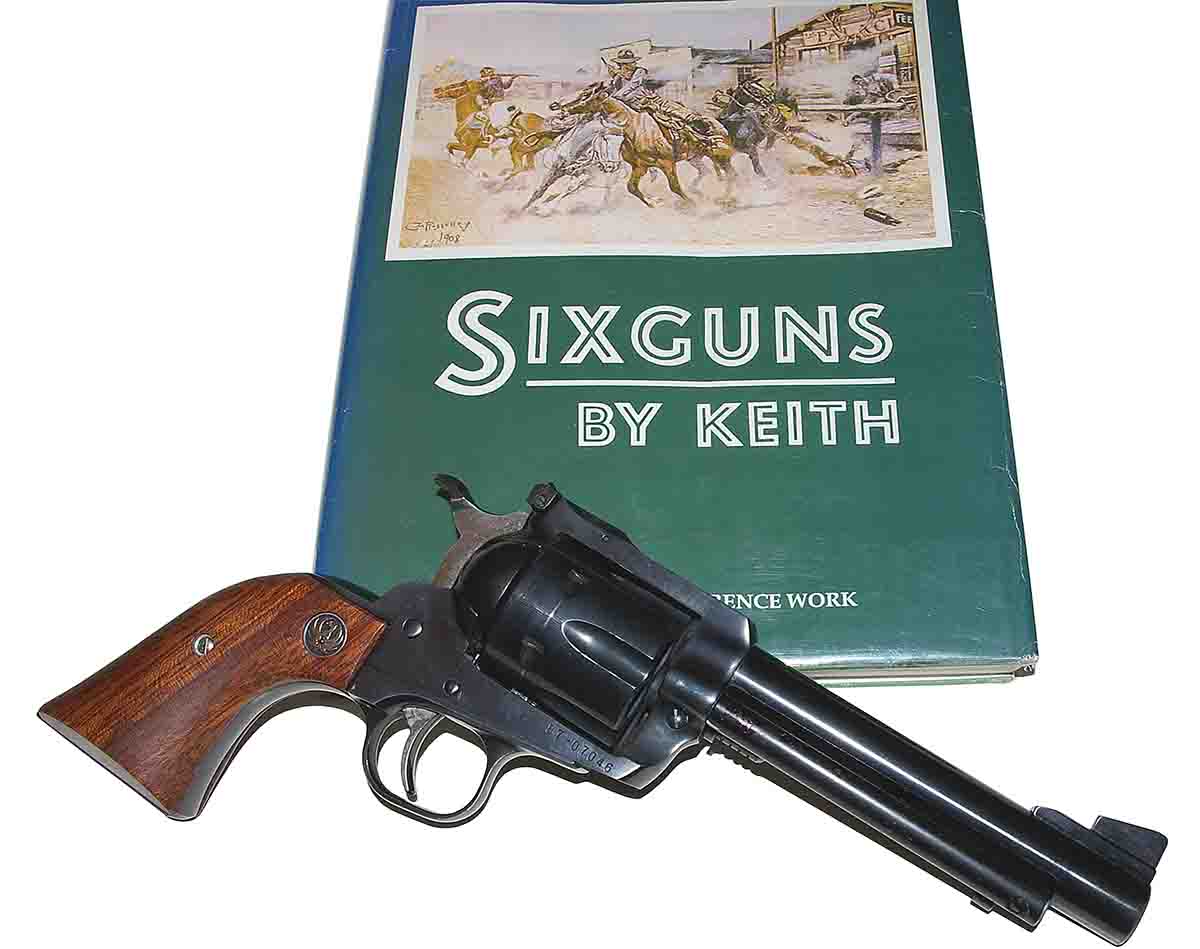

In the following years, however, he promoted the .44 Magnum at every opportunity and, if nothing else, told things the way he saw them. In his book Sixguns by Keith, he routinely describes driving the roads around Salmon, Idaho, and shooting out the window with his .44 at critters and rocks and such. Of course, his most well-known deed with his .44 was shooting a mule deer at 600 yards that his hunting partner had wounded. There is no doubt Keith did exactly that.

I used to live across the alley from Keith’s good friend and rifle builder, Iver Henriksen. Henriksen said one February he was at Keith’s home in Salmon when Robert Petersen, of Petersen’s Publishing, arrived at the door. Petersen was interested in hiring Keith to write for Guns & Ammo magazine, but first he wanted to see if the stories he had heard were true about Keith’s skill with a handgun. Keith was a bit put out that Petersen expected him to prove himself, but he relented and they went out on the prairie to shoot jackrabbits. Keith used his Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum to shoot some sitting rabbits at 100 to 125 yards. Once he got warmed up, he shot a few running rabbits. Petersen hired him on the spot.

Loads

The 1960 Lyman 42nd edition Reloader’s Handbook contains a short article by Keith on “Reloading the .44 Magnum.” In the

article he stated he liked the 250-grain Keith Ideal bullet 429421 in the .44 Magnum “. . . cast no softer than 1 to 16 tin to lead.” He liked a full-power load for this bullet at 1,400 fps with 22 grains of 2400 powder. For a “light gallery load,” he used 5 grains of Bullseye, and for “outdoor targets” 8.5 grains of Unique.

Lyman still sells the 429421 mould and RCBS has nearly the same bullet from its 44-250-K mould. These bullets are designed to place a good portion of their weight in the nose so the body of the bullet takes up less powder space.

Thirty years ago my friends and I used to shoot the exact full-power load Keith suggested from Ruger Super Blackhawk revolvers with 7.5-inch barrels. The bore of the revolvers and fired cases contained quite a few skeletal remains of kernels. So 22 grains of 2400 probably were required for the 250-grain bullet to reach 1,400 fps.

Today’s Alliant 2400 burns more completely, and less of it is necessary to reach that velocity. From the 5.5-inch barrel of my current Ruger Super Blackhawk, 20 grains of 2400 gave the RCBS 44-250-K bullet 1,368 fps 9 feet from the muzzle. Other fully burning powders like W-296 and IMR-4227 also work well with this cast bullet. I’ve shot two whitetail does with this bullet, and both punched holes right through the deer and left a 50¢-sized hole through the far ribs. There’s something about that wide, flat point and sharp shoulder of the driving band that causes considerable tissue damage.

Keith would be amazed at all the heavy jacketed bullets that have come along for his .44. The 240- and 250-grain bullets are

the standard jacketed bullet weights for the .44 Magnum. They clock up to 1,500 fps from a revolver with a 7.5-inch barrel. Even at that velocity, though, I could never get these bullets with a narrow softnose to expand. Years and years ago, I shot a black bear with several of these bullets until it finally gave up the ghost. When I skinned the bear, I found the bullets had penciled clear through, with little damage.

It’s claimed newer hollowpoint bullets readily expand on game. I was skeptical, though, because the .44 Magnum is a relatively weak cartridge, and I thought all its energy should go toward penetration. However, I shot some of these newer bullets into bundles of water-soaked newspapers at 50 yards, and they did expand and penetrate adequately. I used one of the Winchester 250-grain Black Talon bullets to shoot a whitetail doe broadside at 30 yards. It penetrated through the deer and made a nasty wound. I also shot a pronghorn buck at about 80 yards with a Nosler 250-grain Partition. The nose of the bullet expanded somewhat as it passed through the buck’s ribs and lungs and then stopped under the hide on the far side. The buck ran a short way and then fell over on an alkali flat.

All in all, though, these hollowpoint bullets perform no better on game than cast bullets

with a wide, flat point. If you don’t cast bullets, a few good jacketed bullets with flat points are the Hornady 265-grain Flat Point and Speer 270-grain Gold Dot softpoint and 300-grain softpoint. In fact, the Speer Reloading Manual No. 14 states its 300-grain bullet is for handgun hunters who want the performance of heavy cast bullets designed for deep penetration and minimal expansion. The Speer 300-grain bullet reaches 1,200 fps with 2400 powder from my Super Blackhawk, which is about 100 fps faster than the Speer manual states for a 7.5-inch barrel. That load develops all the recoil I care to endure.

I go even lighter for general plinking at cans and such. A 200-grain wadcutter bullet cast from a SAECO 62944 mould and 6.0 grains of Red Dot or 5.0 grains of American Select powder create gentle recoil and mild muzzle blast. My oldest son has also discovered this fun-to-shoot .44 load. That’s why my stash of .44 cartridges is always empty.

But that’s okay. These bullets are cast out of wheelweights, so they cost at the most 2¢ apiece. I used to drop them hot out of the mould into a bucket of water to quench and harden them. But at the slow velocity they’re shot, they really don’t need to be all that hard. So that step has been omitted. The bullets drop from the mould with a diameter of .431 inch, which is just right. I roll them in a jar with a few squirts of Lee Liquid Alox lubrication, spread them out on a piece of waxpaper to dry and then load them.

Did I mention a pound of American Select powder is enough to load 1,400 .44 Magnum cartridges with the 200-grain bullet? That powder can be stretched even farther in .44 Special cases. So my son can shoot cans all he wants.

One Point about Reloading

How much crimp a .44 Magnum case requires is open to debate. A firm grip of the case mouth on a bullet is supposed to check bullet movement for just a millisecond to build pressure, so Magnum cases full of slow-burning powders burn uniformly and completely. Even light amounts of fast-burning powders in large cases supposedly require a tight roll crimp to prevent squib loads. Most importantly though: A bullet without the proper amount of crimp may unseat due to repeated recoil when other cartridges in the cylinder are fired. A bullet that is pulled far enough out of the case may protrude out of the face of the cylinder, preventing the cylinder from rotating.

To establish how much of a crimp is required, I shot three different loads from the Ruger Super Blackhawk .44 Magnum with no crimp, a medium amount of crimp and a tight crimp that was just short of bulging the case. Velocity spread shrank the tighter the crimp with a jacketed Speer 200-grain Gold Dot bullet and 26.0 grains of W-296 and the Speer 300-grain softpoint and 21.0 grains of W-296. However, the relatively slow burning W-296 didn’t burn more completely to produce higher velocity with an increasingly tighter crimp. With the mild load of 6.0 grains of Red Dot powder and the Speer 240-grain swaged lead bullet, velocity spread was only about 15 fps between cartridges with no crimp to a heavy crimp.

I fired five shots with each load and then removed the sixth cartridge to measure its length to see if the accumulated recoil had pulled the bullet past the crimp. The recoil was substantial with W-296 and the 200- and 300-grain jacketed bullets. Yet with the three different amounts of crimp, the sixth cartridge with each load did not increase in length. That could be attributed to the reloading die’s expander plug that sized the inside of the case to .423 inch and put a tight grip on the copper jackets.

The swaged lead bullets did pull out of the cases, even though recoil was gentle. That’s because lead and the lubrication on them were slippery and provided little purchase for case walls. With no crimp, the lead bullet from the sixth cartridge pulled out of the case .10 inch. The medium and heavy crimp on the swaged lead bullet reduced bullet movement to an ever so slight amount.

I can shoot all afternoon without numbing my hands or my wallet with an easy recoiling load like that swaged lead bullet and light amount of Red Dot. The recoil of stout Magnum loads is also bearable, even though my .44 weighs one-half to a couple of pounds less than revolvers in larger caliber Magnum cartridges. That means I will pack a .44 on my hip when I need it close at hand, hiking in the summer after small game or with a watchful eye for bears while packing out a load of elk meat in the fall.