Black Powder Big Bores

The Evolution of Big, American Cartridges

other By: Mike Venturino, Photos by Yvonne Venturino | July, 25

The first factor to consider is: What constitutes a big bore? The answer to that is subjective and relative. A .22 rimfire shooter might consider a .30-06 a big bore. In years gone by, I thought of a .38-55 WCF as a “big bore.” As judged by my current shooting interests, a .38-55 is at most a mid-bore, as are all .40-caliber, black-powder cartridges, with the possible exception of the .40-25⁄8 Inch Sharps Bottleneck (aka, .40-90 Sharps).

For the purposes of this article, black-powder cartridges over .40 caliber are big bores, shooting with sufficient power to take game as large as bison or propel a bullet accurately to 1,000 yards in target shooting. There is also the consideration of duplicate cartridges, i.e., those actually being the same dimensionally but bearing different names. For example, what is generically called the .45-90 could be found by two names in the late 1800s. It started out as the .45-24⁄10 Sharps and was never loaded with bullets weighing less than 500 grains. Winchester adapted that same length case to its Model 1885 Single Shot and Model 1886 lever action using 300-grain bullets. Then its name was .45-90 WCF (Winchester Center Fire).

Some cartridges developed by lesser known companies will also be ignored. For instance, Ballard had its own proprietary cartridges, as did Bullard, Maynard and others. Cartridges such as Winchester’s .44 WCF (.44-40) will not be covered herein, because bullet diameter is large enough but its powder charge makes it nowhere near a true big bore.

Some readers might be thinking that doesn’t leave them much to consider. Well, yes, it does. Between Sharps Rifle Company, Winchester Repeating Arms, Remington Arms Company and Marlin to a lesser extent, there were plenty of big-bore, black-powder rounds developed and sold in significant numbers.

As with so many American cartridges that gain significant popularity, the genre of black-powder big bores began with one introduced circa 1866 by the U.S. government, the .50 Government (.50-70). Chambered in Springfield Models 1866, 1868 and 1870 for the U.S. Army, it was quickly adopted by Remington for its post-Civil War rolling-block design. The Sharps outfit followed in 1867 and 1868 by converting paper cartridge Models 1859 and 1863 rifles and carbines to it. The .50 Gov’t was also one of that company’s chamberings for its first sporting rifle, the Model 1869.

Government .50-caliber loads used 70 grains of black powder in 1¾-inch straight cases with 450-grain grease groove, conical-shaped bullets. Velocity was rated at 1,250 fps from 325⁄8-inch trapdoor Springfield barrels. It was one of the most fired cartridges by both sides during the Plains Indian Wars of the 1860s/ 1870s.

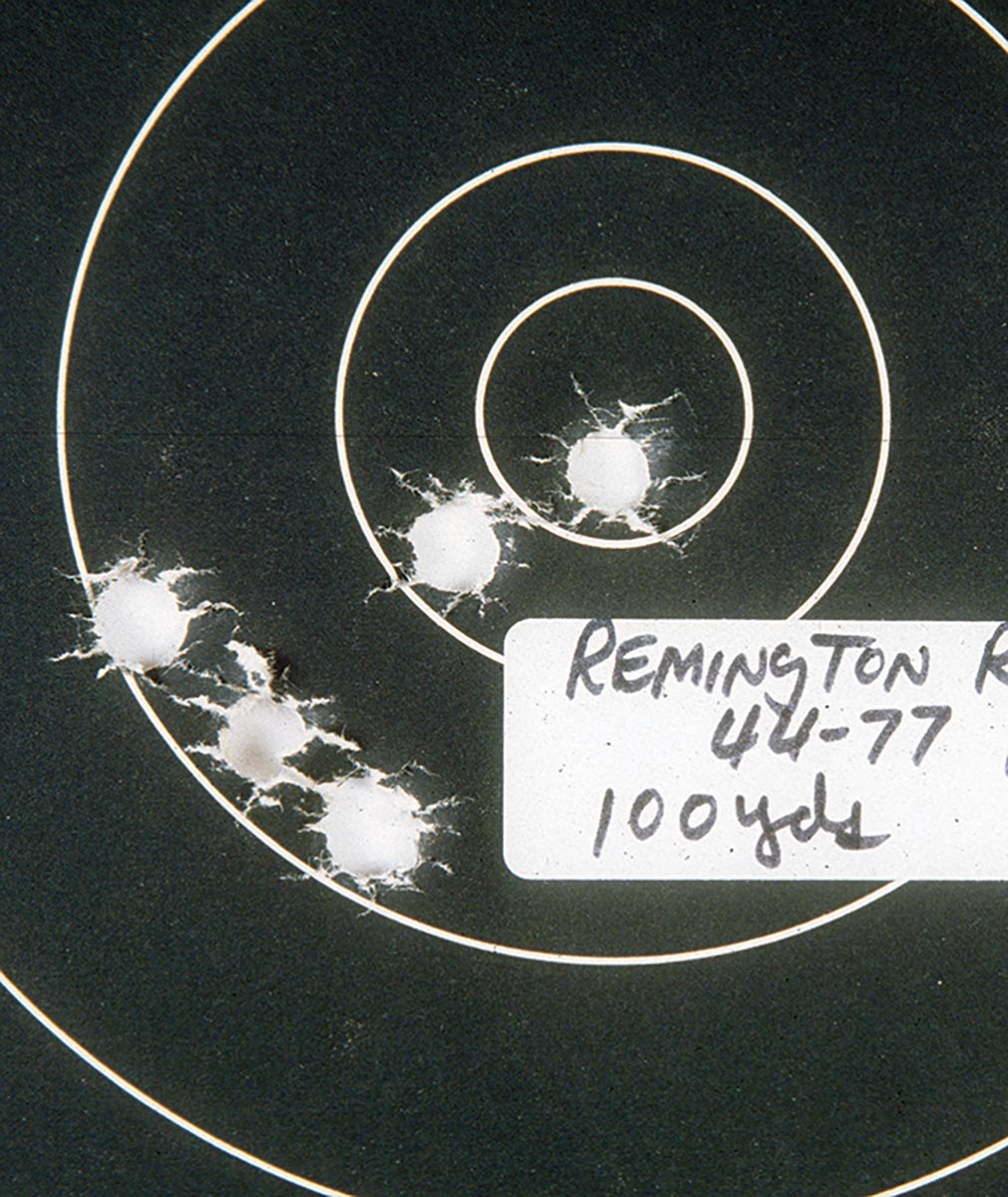

What most likely was the second big-bore, black-powder cartridge sold in numbers in the U.S. might strike readers as odd. It was the .43 Spanish developed by Remington primarily for military organizations of Spanish-speaking nations but also cataloged domestically. Loads differed by nations, but Remington’s factory load used .439-inch, 370-grain bullets over 77 grains of powder. Cartridge cases were 21⁄4 inches long and bottlenecked in configuration. Remington’s 1877 catalog listed military-style .43 Spanish rolling-block rifles at $16.50 and a 1,000-round case of factory ammunition at $38.00.

The great bison slaughter began in 1871 and caused the Sharps Rifle Company to develop several other big-bore rounds and introduce a new single shot. It actually was merely a remodeled version of the ’69. Usually the new rounds were merely lengthened versions of the .44 and .50 calibers mentioned above. For example, the .44-25⁄8 Sharps featured the same case head and bullet diameter as the .44-77, but the powder charge was upped to 90 grains and bullet weight increased to 450 and 500 grains in Sharps factory ammunition. The same method was used in .50-caliber rifles. The government-designed, 13⁄4-inch case was lengthened to 21⁄2 inches and filled with 100 grains of powder under 425-grain, grease-groove bullets or 473-grain, paper-patched types. Both the .44-90 and .50-90 rounds, as we know them today, were introduced in the early 1870s, but sources vary as to exact year. (The Sharps Company never loaded the .50-21⁄2 inch with less than 100 grains of powder. That .50-90 name we use today came in the 1890s, when Winchester loaded it with only 90 grains.)

Until the advent of .45-caliber cartridges, pioneered as usual by the U.S. government, the big-bore, black-powder cartridge situation remained static. Some evidence of this has appeared in the findings of archeologists digging at the Adobe Walls site in the Texas Panhandle. There in June 1874, a fight occurred between about 28 buffalo hunters and several hundred Comanche, Kiowa and Southern Cheyenne warriors. From behind the settlement’s walls, the buffalo hunters beat off the Indians, suffering only three deaths, all during the initial charge. Exact Indian deaths are not known, except that the bodies of 13 warriors could not be retrieved by them. Several more were. The archeologists recovered numerous fired cartridges and even loaded rounds from the building sites. Except for pistol cartridge cases, all were .44-77, .44-90, .50-70 and .50-90.

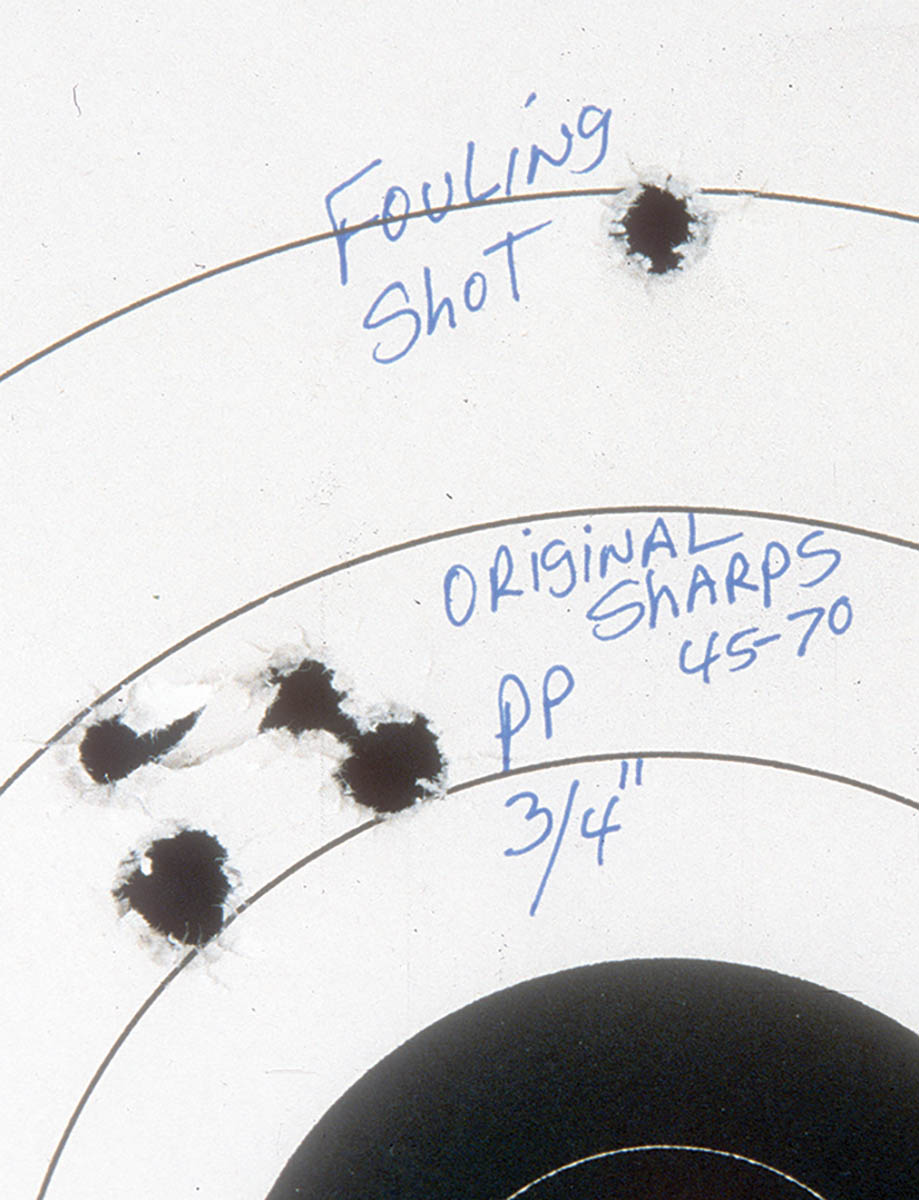

After years of experimentation, the U.S. Army’s Ordnance Board settled on a .45-caliber cartridge with a case length of 21⁄10 inches and a grease-groove bullet of 405 grains, .457 inch in diameter. Powder charge was 70 grains. During the next 20 years, a carbine load with only 55 grains of powder was adopted, and in the 1880s, a rifle load came with a 500-grain bullet over the 70-grain charge. Both Remington and Sharps quickly added the new cartridge to their sporting rifle options. Remington was happy to follow the government’s lead and varied little from the original loads’ components and ballistics. Sharps preferred to offer the new round with a 420-grain paper patch bullet and 75-grain powder charge.

Sharps Rifle Company then set about to “improve” on the government’s basic development, using case lengths of 24⁄10, 26⁄10 and even 27⁄8 inches. Interestingly, the first two “improved” cartridges were billed for target shooting, but the longest one, along with the original 21⁄10-inch versions, were sold in sporting rifles. Bullet weights for the “improved” rounds were (usually) 500 grains up to 550 grains. Their common names today, in the same order, are: .45-90, .45-100 and .45-110.

During the 1870s, Oliver Winchester must have felt sorely put upon. His new-fangled repeating rifles were popular except to those hunters going after truly big game, such as elk, moose, grizzly bear and, of course, bison. So by 1876 the Winchester Repeating Arms Company tried to upsize the Model 1876 so it could compete with Sharps and Remington single-shot rifles. Only two of its four cartridges barely make my self-imposed criteria for black-powder, big-bore status. They are the .45-75 WCF and .50-95 WCF. The Model 1876 was limited to cartridge length, so these rounds only have case lengths of 1.89 and 1.94 inches in the same order. Their factory load bullet weights were also light for their diameters at 350 and 300 grains, respectively. The Model 1876 Winchester sold in fewer numbers than any other Winchester levergun.

After the failure of the 1876’s cartridges to gain a solid following, Winchester stayed out of the big-bore rifle market until John M. Browning joined its engineering staff. When his Model 1885 single shot appeared, the company billed it as an improvement on the basic Sharps style of action, i.e., a falling block. Thusly it could accept any cartridge length, and among the 80-plus Winchester single-shot chamberings were two immense ones. The company lengthened the basic .45 and .50 Sharps rounds detailed above to 3½ inches. Today such rounds are called .45-120 Sharps and .50-140 Sharps. Neither were ever Sharps cartridges. They were also failures in Winchester’s single shot merely because they were too much of a good thing. Recoil was horrendous, and as said, their only advantage was to make a larger hole in the ground after their bullets passed through a game animal.

With the Model 1886 levergun, Winchester finally did enter the big-bore, black-powder cartridge market – barely. Marlin actually beat them to the punch with the Model 1881 and .45-70 Marlin cartridge. Special factory ammunition using flatnose bullets was developed for it due to magazine explosions with the government-style roundnose bullets.

Winchester first offered .45-70 and .45-90 chambers in that model but varied them greatly in one respect. The .45-70 had a rifling twist rate of one turn in 20 inches that would stabilize longer bullets up to 500 grains. The .45-90 ’86s were meant for light, 300-grain bullets and used one-in-32-inch twist rates. With a velocity of at least 1,500 fps, the .45-90 was suitable for elk and moose, but perhaps such a light bullet would not give suitable penetration on bison.

Winchester’s last attempt for a truly big-bore, black-powder cartridge was its .50 that came in both the levergun and single shot. The .50-110 Express used a 300-grain bullet over 110 grains of black powder. As best as my research has been able to determine, rifling twist rate was one turn in 60 inches. The second version used the same 2.40-inch case but with 100 grains of black powder and 450-grain bullets. Again, as best I can determine, its rifling twist rate was one turn in 54 inches. Both cartridges could safely be fired in rifles meant for either, but best performance would come when cartridges were mated with proper rifling twist rates. Neither of Winchester’s .50-caliber rounds sold that well in leverguns. Model 1886s chambered for .50-110 were made to the tune of about 6,000, but only about 10 percent were made for the cartridge using 450-grain bullets.

For nearly 30 years, a great portion of my writing career centered on reloading and shooting the rifles and cartridges mentioned in this article. That included casting bullets as close to factory original as possible and propelling them in original rifles by means of straight black-powder charges. Here and there some big-game hunting was also done with them. My book Shooting Lever Guns of the Old West is sold by Wolfe Publishing Co., and Shooting Buffalo Rifles of the Old West should be in Wolfe’s 2015 catalog. For load data to detail the black-powder cartridges described in this magazine, I have leaned on the work done for both of those books.

.jpg)