How to Develop Accurate, High Performance Handloads

Load Development

other By: Brian Pearce | February, 26

Priming is an often overlooked step of handloading, but plays an important role in how ammunition performs. Generally

Choosing the correct primer is also of paramount importance. Let’s say we are handloading the .44 Magnum. Naturally it takes a Large Pistol primer, but many deduct that since it’s a magnum cartridge it will require Large Pistol Magnum primers. Unfortunately it is not that simple. There are many excellent powders for loading the .44 Magnum that actually give better accuracy and less pressure when used in conjunction with standard primers. On the other hand, there are many other powders that need a Magnum primer to ignite correctly, and using a standard primer has proven (in laboratories) to produce erratic pressures and velocities. While the .44 Magnum has been used as an example, similar results can be seen with other cartridges, both pistol and rifle.

Developing Loads for High-Pressure Bottleneck Rifle Cartridges

After cases are inspected, sized, trimmed (if necessary) and primed, let’s begin developing a load. Unless one has education and experience at developing load. Unless one has education and experience at developing loads, published data should always be referenced. Do not use loads from unknown sources, which seems prevalent on the Internet. Most reloading manuals list powder charges that have been carefully pressure tested. The “beginning” or “starting” loads are usually at least 5 percent below maximum. Having experience at developing handloads for more than 150 different cartridges and many more guns than that, I must emphasize the importance of beginning with “starting” loads before attempting “maximum” loads. Not all guns for a given cartridge share identical dimensions. A short throat, an abrupt leade, tight groove diameter or other small

After charging cases with a “beginning” powder charge, seat bullets to correspond with suggested SAAMI overall cartridge length; they should more or less duplicate factory ammunition lengths. (More on bullet seating depth and overall cartridge length in a moment.)

Fire a few rounds, carefully checking each case for signs of excess pressure. (This is where achronograph is valuable in determining if a load is close to duplicating factory loads or the advertised velocity of the load you have selected. If speed is similar (and with correct powders), pressure is probably similar too. Contrary to what has been widely published, primer appearance is not always a good indicator of pressures, as there are simply too many variables. Nonetheless there should be no signs of rupturing. Primers that are pierced and/or cratered (wherein the firing pin indentation is pushed back) can indicate excess pressure but is often due to a rough firing pin that is incorrectly shaped or too long. Cratered primers are often the result of a poor fitting firing pin/firing pin hole or a firing pin spring that is too weak. Flattened primers do not necessarily indicate the load has excess pressure or is dangerous.

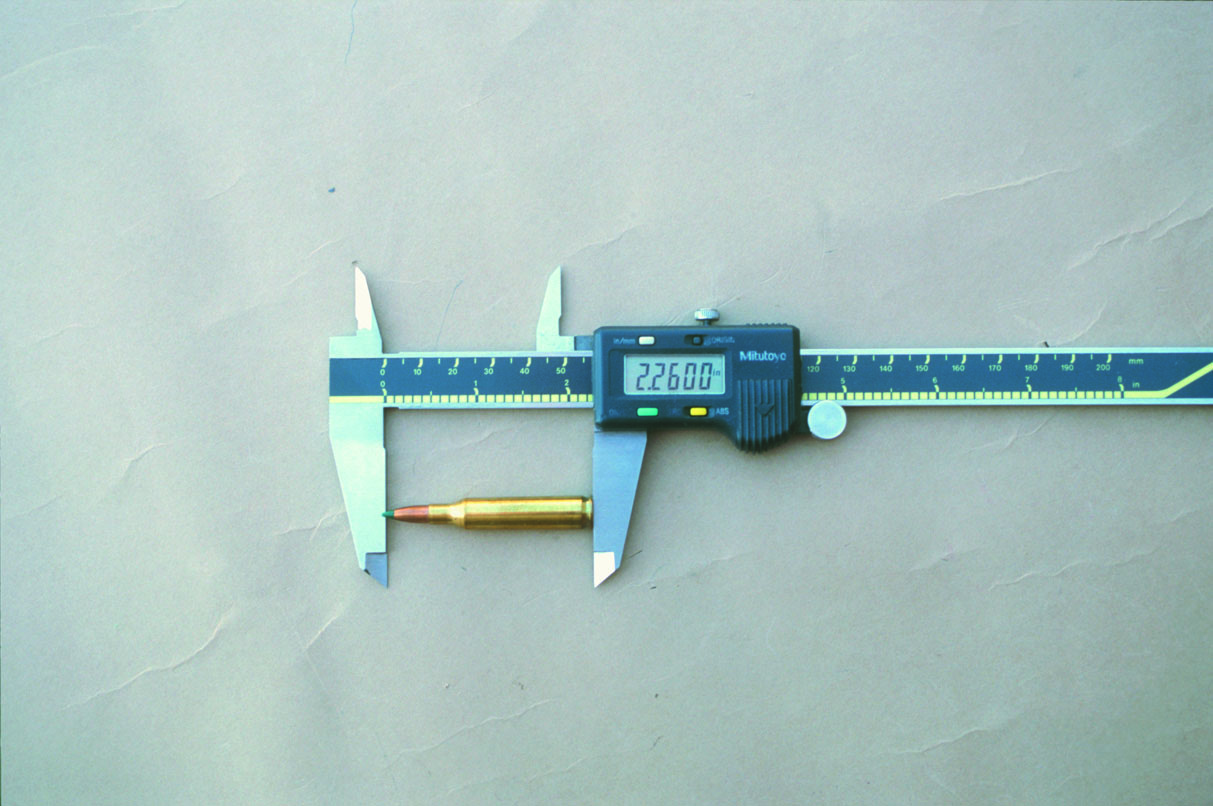

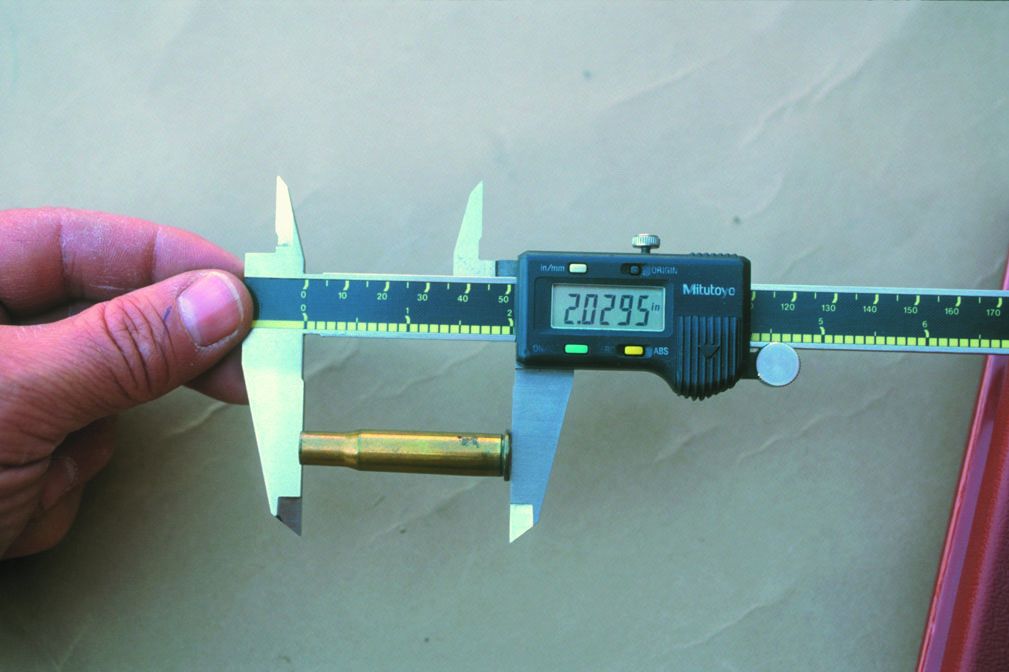

At this point a blade-type caliper that is capable of measuring 0.0001 inch will prove a valuable tool in determining the safety and approximate pressure of your handload. If you are using new, unfired cases to develop your new load, case head expansion may vary more than cases that have been once-fired prior to developing loads. It is better to begin with once-fired cases, as their webs will be settled and readings will be more accurate. Cases should be of the same make, as hardness varies by manufacturer and so will case head expansion. Measuring the diameter of the head, just above the extractor slot but below the case body in the web area, before and after firing will give an indication of pressure. Most modern high-velocity bottleneck cartridges, such as the .243 Winchester, .270 Winchester, .308 Winchester as well as the 7mm Remington Magnum and similar rounds, will expand case heads .0003 to .0005 inch and are generally considered to be around 50,000 CUP (not psi). This is approximately equal to most factory loads and is generally considered maximum.

Assuming your starting loads are below maximum pressures, fire a few groups (from a proper sandbag rest) to see how that load is performing in your gun, then record their sizes. In an attempt to fine-tune the load, seating bullets out closer to the rifling will often, but not always, increase accuracy. The maximum overall cartridge length (or just how far we can seat bullets out) is usually determined by two factors in typical bolt-action repeating rifles. First, bullets must fit and function correctly in the magazine, and second they must chamber properly. Single-shot rifles are only affected by overall cartridge length, while tubular magazine guns (leverguns, pumps, etc.) must feed correctly and are sensitive to overall cartridge length.

Seating bullets out until they contact the leade or rifling often results in problems such as a stuck bullet in the bore when a

Through trial and error, the exact maximum overall cartridge length can be determined for a specific rifle. The bullet should be at least .0010 inch off the rifling. Please note that the ogive profile of bullets varies considerably from one maker to the next and from one style to another. The point being the overall cartridge length will necessarily change from one bullet to the next to prevent bullets from contacting rifling. Again, record the group sizes after each change. (Seating bullets closer to the rifling often improves accuracy, but not always. Occasionally rifles will shoot better with bullets seated deeper.)

If this approach has not provided desirable results, and all possible accuracy problems with the rifle have been eliminated, the next step is to try different components including bullet, powder and primer combinations. Some guns will show a strong preference with given bullets but might not shoot particularly well with others. With experimentation, loads can usually be developed that will produce better accuracy than factory ammunition.

It should be noted that if ammunition is to be used in several rifles, loads should have similar overall specifications as factory loads to assure reliable feeding and chambering.

Tips for Developing Revolver and Pistol Cartridge Loads

The majority of pistol and revolver cartridges operate at much lower pressures than modern bottleneck rifle cartridges. For example, the .38 Special has an industry maximum average pressure of 17,000 psi, the .44 Special 15,500 psi, the .45 Colt 14,000 psi, while magnum rounds such as the .41 and .44 Remington Magnums generate 36,000 psi. The .45 ACP runs 21,000 psi or less. The point being, most handgun loads are low pressure when compared to bottleneck rifle cartridges and it is difficult to accurately assess pressures. The difference in case head expansion, at least on most cases, is undetectable using blade calipers (for example, a .38 Special load that is generating 15,000 psi versus another that is producing 25,000 psi). Careful examination of primers can help determine if one load is producing more or less pressure than another. A flattened primer is probably producing greater pressure than one that is “rounded” at the edges, but standard pressure loads in the .38 Special, .44 Special and .45 Colt cartridges will generally all have rounded edges.

Another common mistake includes incorrect seating of bullets. Hornady and Speer offer 300-grain .44 Magnum bullets with a double cannelure, and there has been much data developed for the Ruger Redhawk with the bullet seated out and crimped in the lower cannelure. If these bullets are seated in the upper crimp groove, pressures will increase substantially and will probably be dangerous if the powder charges are not decreased. Again, attention to detail will help assemble safe loads.

With the above warnings out of the way, following are some suggestions to develop accurate, high-performing loads for your favorite handgun.

Begin with dies that are correctly dimensioned. The sizer die must reduce cases enough to allow proper chambering and

One problem that occasionally surfaces with straight-wall revolver cartridges includes the case mouth “biting” into cast bullets during the seat/crimp operation, which is often performed as one step. First make certain that the case mouth is being expanded sufficiently, which will allow the bullet’s base to be started into the case at least 1/16 inch and sometimes as much as 1/10 inch. If the die is adjusted correctly and the problem exists, bullets will need to be seated without any crimp applied, then as a separate step the crimp applied.

Commercial bullet companies such as Hornady, Speer, Nosler, Sierra, Barnes (actually solid copper) and others offer top-rate jacketed bullets that generally shoot

When it comes to cast bullets, designs and quality, commercial offerings vary so much that results can range from extremely poor to excellent. A complete discussion could fill volumes, but suffice to say that using proven designs that have been around for many decades will generally give the best results. (There is a reason certain cast bullet designs and loads have become and have remained popular for generations.)

The same as rifles, handgun loads should be checked for accuracy from a proper rest or comfortable shooting position. Again, through experimentation of bullet designs, weights, powder types and charges, handloads can duplicate and even exceed factory load performance in terms of accuracy and velocity. This article was reproduced by permission from LoadData.com.