My Journey with the .222 Remington

other By: Stan Trzoniec | April, 26

While the .222 Remington was introduced to the shooting public in 1950, it wasn’t until many years later I acquired my first rifle in that cartridge. As I recall, it was a used Remington 722 purchased when I came out of the Army as a helicopter crew chief around 1964. Topped off with a well-used Weaver scope, it did serve my purpose of varmint hunting in the northeast for years to come. Later, I got the bug for a really nice rifle in the triple deuce but I will get to that momentarily.

The .222 Remington was a “house” cartridge, meaning it was born within the hallowed walls of Remington Arms, by a dedicated employee and shooter named Mike Walker. Within a short time, this .22 cartridge took off to the point where the parent company had a hard time keeping up with demand. Evidence of that is in the copy of a letter that I received from then public relations manager Dick Dietz.

In the letter to their jobbers on March 30, 1950, by Sales Manager R.C. Swan, he mentioned that “orders to date have dwarfed even our own optimistic forecasts and have cleaned out our stock in an amazingly short time.” Swan went on to say that a revised production schedule will ensure better service in the future with reference to this cartridge. Along with the timing of the production of the cartridge in the Model 722 short action rifle, this is the perfect (Swan’s words) “combination for varmint shooting to include woodchucks, coyotes, wolves and other small game.” Later Sako would add the .222 to its L46 series of rifles. Praising the new .222 Remington in the same letter, he compares it to the Hornet with figures that overwhelming showed the

.222 Remington against the Hornet with velocity readings 20 percent higher and muzzle energy 62 percent better at the muzzle, all with a downrange factor that is 37 percent flatter at 100 yards than the .22 Hornet. Finishing up, Swan suggested that his jobbers order now for upcoming activities in the spring and summer hunting seasons. At that time, all this seems like it was only the beginning of this great addition to the small game world of shooting.

Looking back, the ballistics of the .222 Remington meant a lot to aspiring varmint hunters. They could shoot further, have less bullet drop at 100 yards, and have a production rifle to shoot, even for the budget-minded shooter. I had that Model 722 until 1976, when I traded it for Ruger No. 1 and the high-stepping .22/250 Remington. Even though some of the reports stated the Ruger No. 1 was not very accurate and to make it so resulted in placing rubber washers under the fore end screw. I never found

the Ruger wanting for accuracy, even without the rubber washer, and after some range time and trigger-tuning, I found that 33.6 grains of IMR-4320 under a 55-grain Hornady bullet gave me groups of around a half-inch at 3,500 feet per second (fps).

Now fast-forward to 1989 when I got the bug again for the .222 Remington and wanted something special and first class in a rifle. Working with Remington over the years and with my interest in custom rifles, I developed a relationship with Tim McCormack, then head of the Custom Shop in Ilion, New York. Tim was very knowledgeable person when it came to custom-built rifles and he helped me on a number of magazine assignments dealing with the shop. I expressed an interested in a specially built Remington Model 700 that I could use in the fields of upstate New York for woodchucks. Before I left the shop, I had the order form in my hands, filling it out in my mind as I drove home.

In short, an order was placed for a Remington Model Grade I Model 700 in .222 Remington with a 24-inch medium weight

barrel with all metalwork in a matte finish. To match my other “family” of rifles, I wanted a satin finish on the stock complete with ebony tips, a black recoil pad sans a white spacer (remember those?) and since this was a custom rifle, I desired the forearm be extended a few extra inches for ease of resting the rifle in the field. Naturally, I was hoping for a stock with a nice grain pattern if possible, and a few months later, the rifle was completed matching my requests perfectly. With the rifle in my hands, I mounted a Bausch & Lomb 12-32x power scope in Redfield rings and bases.

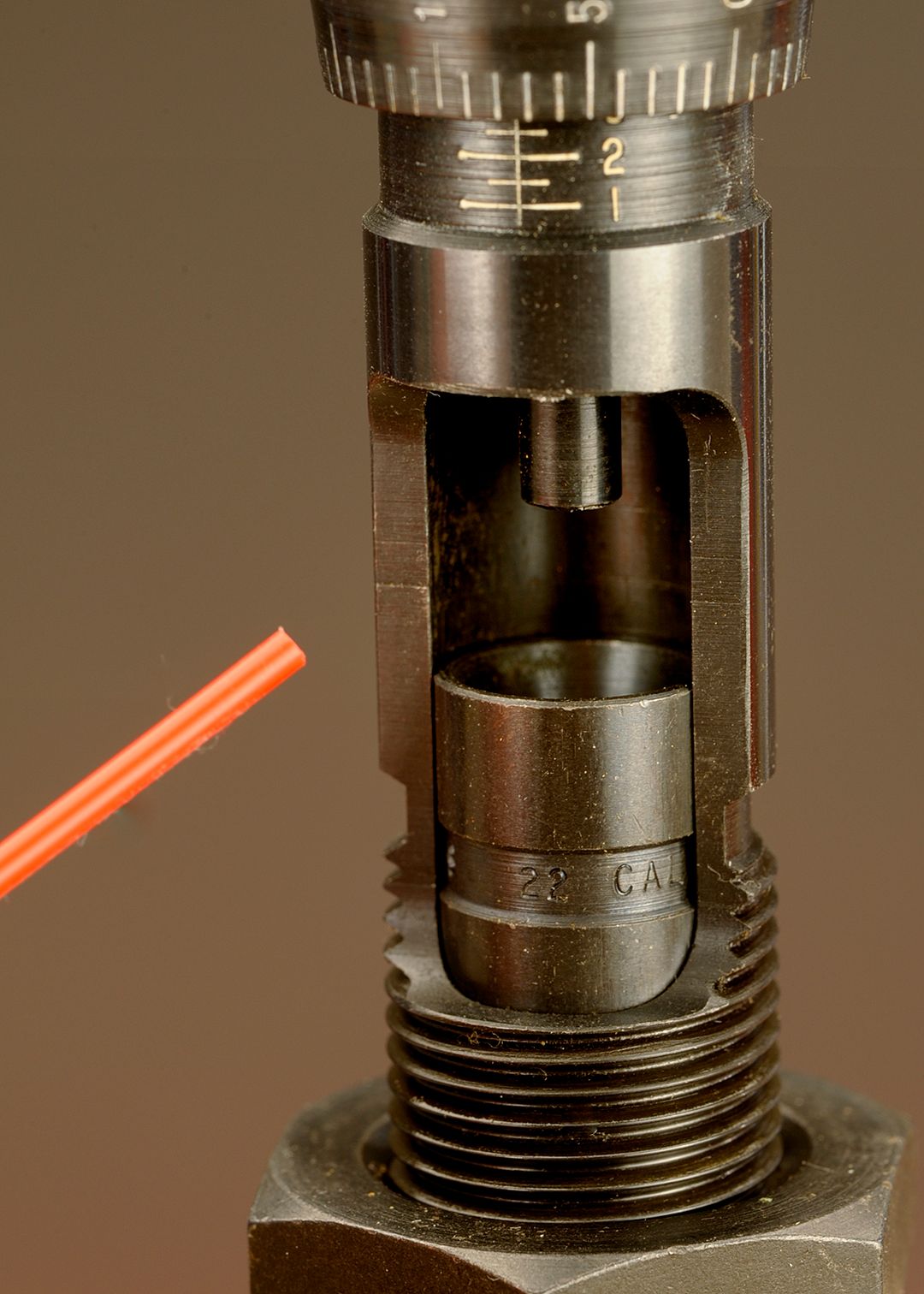

During the production time of the rifle, I gathered up some nickel-plated match Remington .222 brass from Federal for that special touch to my handloads. Along with all this, I purchased a set of special order RCBS Bench Rest dies with an interesting type of a micrometer adjustment at the time for seating bullets to the thousandths of an inch. The one thing I liked with this die set is the ability to insert smaller caliber bullets through the side of the die body instead of placing them on the mouth of the case under the die leading to tipping or even destruction of the case mouth. Quoting from RCBS literature, that stated, “The Gold

Medal Seater Die features a micrometer adjustable, free-floating and self-centering bullet seating system with a convenient bullet-loading window. This allows the bullet to be seated in precise alignment with the cartridge case.” This was just the set I was looking for and they still make it today. The .222 Remington takes small rifle primers and during the testing, I used regular and benchrest type, with the Federal 205M leading the pack after I was finished.

I looked into powders during the testing and I used Reloader 7, H-4895, Winchester 748 and IMR-4198 as recommended by my fellow varmint hunters for use in small capacity cases. Naturally, all your friends try to chime in when a new rifle comes, that is part of the deal with fellow shooters, but research showed most anything from IMR-4198 to IMR-4320 would fill the bill if you have enough time, patience and money to explore them all. Taking delivery of the rifle in the early spring proved that I had to get going with handloads if I wanted to extend my summer small game and varmint hunting.

Fireforming cases gave me an ample supply to which I neck sized all. Bullets were next and after all the testing with the gun; I found that bullet weights from 50 to 55 grains were going to be the best for my use. I found out early, and even with the No. 1, that these weights seem to balance .22 caliber rifles and the .222 Remington had what I was looking for in velocity, trajectory and of course, accuracy. Looking at all the .224 bullets available, it is certainly a buyer’s market and with the .222, a handloader could spend a lifetime getting that just right load for your pet rifle.

Bullets from Hornady, Nosler, Remington, Sierra and Speer all got a fair shake during the testing program and with the rifle broken in that summer; I had some good results to fall back on.

For powders, I burned a lot of midnight oil on research and if you read between the lines, there is a lot of information available. With the help of Ken Waters and his tome on Pet Loads (Wolfe Publishing), I was on my way to tightening my grip on a selection of the proper powders for my use in the .222 Remington. What I found in his massive work of 1,166 pages and other books and how it all worked out in the end with the recommendations of his on the .222 Remington.

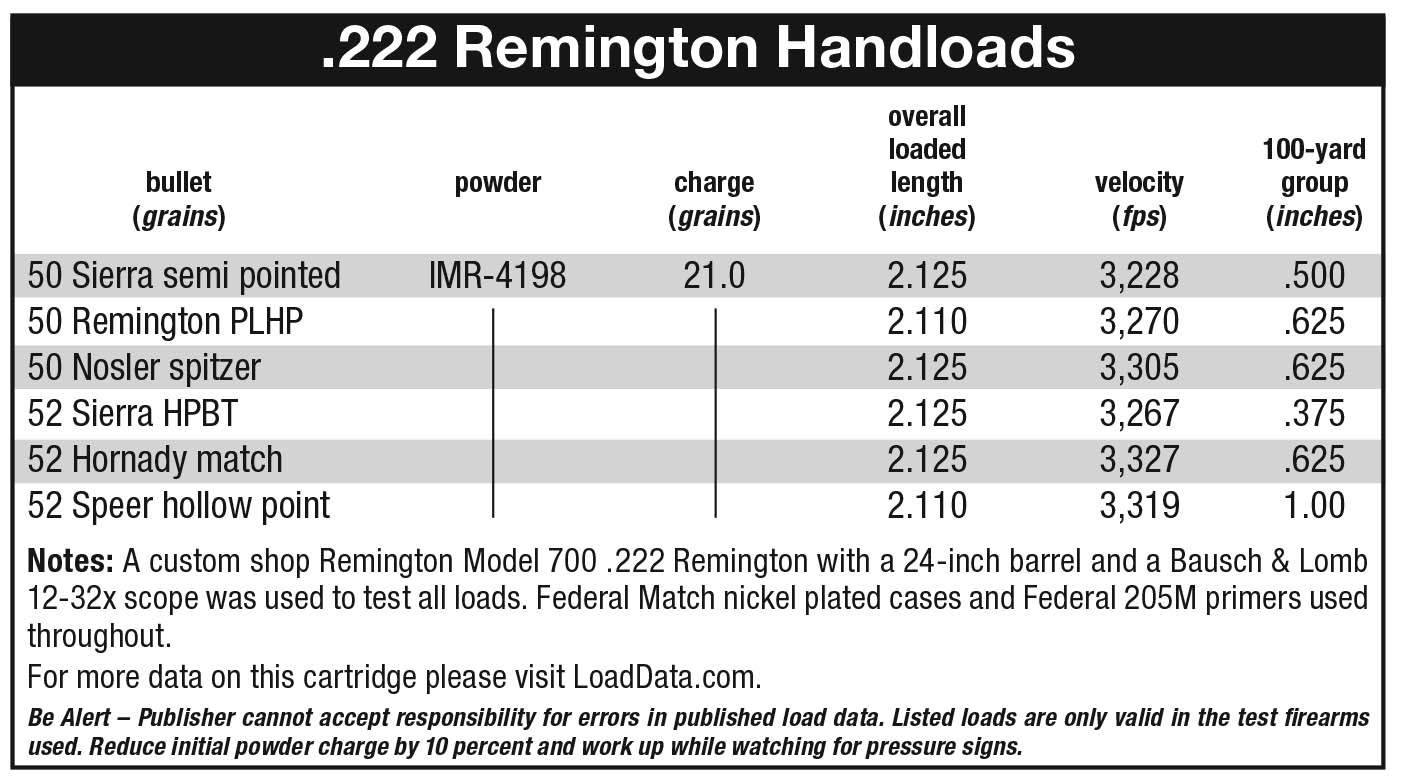

One of the first references was in the book titled, “Propellant Profiles,” where powders of all kinds are reviewed. Right there in his pet loads, John Wootters liked 20 to 21 grains of IMR-4198 under a 50-grain bullet for 3,230 fps with the latter. My testing showed I got 3,228 fps and later proved IMR-4198 did produce the highest velocities.

Moving on to the Waters’ book, Warren Page stated his preference to IMR-4198 for the 50 to 55-grain bullet. Starting out with 19 grains, he worked up to 20.5 grains for 3,200 fps. The late Townsend Whelen used 20.5 grains of IMR-4198 and found it very accurate with some of his tightest groups shot with that powder. Waters wrote that in using IMR-4198 in his .222 Remington Update, both 20.5 and 21 grains were used in the charts with one load consisting of the 21 grains, which were extremely accurate to the tune of 9/16 inch (.562”) for 3,297 fps. Finally, Mike Walker who had a big part in the design and the birth of the .222 Remington started out with 21.5 grains of IMR-4198 but later reduced it to 21 grains which proved to be the most accurate load in my rifle. In the end, reading about and researching a cartridge for the optimum powder charge always brings out interesting facts and will save time and effort at the range.

In reviewing my own experiences with the .222 Remington, all three of the 50-grain bullets from Sierra, Remington and Nosler came very close to each other in the accuracy department, in fact, to one-eighth of an inch apart. Velocity was very close and take note that I checked the weight of 10 each of the various bullets (for an average) just to show the close manufacturing tolerances we enjoy today. These 50-grain bullets averaged 50.1, 49.1 and 50.1 in weight right out of the box.

With the 52-grain Sierra, Hornady and Speer, the Sierra had the best of all with groups on a regular basis hitting the tight side of .375 inch time after time. Hornady’s 52-grain Match came in a notch over a half-inch while the Speer hit an inch. Later testing over the past summer showed the Speer getting better with 3-shot groups circling around .750 inch with another batch of bullets doing the trick. Factory ammunition from Hornady and Remington did their thing with Hornady being on the lower side (one inch) in the accuracy department and Remington higher around three-quarters of an inch.

Finishing up, the .222 Remington still has a lot to look forward in reloading and shooting. The cartridge is easy to reload, there are plenty of components out there to experiment with, recoil is light and accuracy can be fantastic. The cartridge may be in its senior years now, but still has a great following as both a varmint and benchrest cartridge. At 70 years on the market, for those who have never tried it simply because they might have been captivated by newer cartridges, get out in the field and give it a shot.