Ruger No. 1

An All-American Favorite

other By: John Haviland | February, 26

The No. 1 was called the “Victorian” during its development. Roger Barlow refers to the rifle by that name in his article “Ruger’s Reactionary Rifle” in the 1967 Gun Digest. From the public launch in 1967 and onward, though, the rifle has been called the “No. 1.”

Hand-checkering of No. 1 stocks was converted to machine-cut checkering years ago. Gurney calls it “engraved checkering,” and he said stock wood is like March weather in New England. “Some of it’s good, and some of it’s bad. We separate and sort through it [as] best we can.” Lately Ruger has been paying more for better wood.

From the No. 1’s beginning, its major parts have been produced by investment casting at Ruger’s Pine Tree Castings in Newport, New Hampshire. The rifle’s receiver, breechblock, lever and lots of little bits and pieces are still investment cast.

Gurney said the late Stan Terhume started Pine Tree Casting in 1963. “I consider Stan as Ruger’s most important employee, right behind founder Bill Ruger, because long before there was e-mail and computers, Stan had Pine Tree Castings up and pouring steel in nine months,” he said. Terhume’s ability to take a product from conception to production was an immense help in quickly bringing the No. 1 to market in 1967 – and introducing Ruger firearms one after the other during the 1970s and 1980s.

Over the years Ruger catalogs have listed the No. 1 in a vast array of models. In the vicinity of 45 cartridges have been chambered in those models, from the .204 Ruger up through the .300 Weatherby Magnum and .458 Lott. Special runs of rifles chambered in such cartridges as the .303 British and .357 S&W Magnum have pushed the number even higher. Gurney said chambering the No. 1 action for different cartridges is relatively easy, because there is no worry about cartridges of different shapes and lengths fitting in or feeding from a magazine. “To chamber different cartridges, you just need the right chamber reamer,” he said.

Over the years many of these cartridges have been chambered in different models with blued or stainless steel and walnut stocks, stainless steel and laminated stocks, different recoil pads, etc., and a collector of No. 1s will be forever destitute.

In contrast, today few models and cartridges are currently available in the No. 1. The only options are the 1V (Varminter) .223 Remington, 1RSI (International) 6.5x55, 1B (Standard) .257 Weatherby Magnum, 1S (Medium Sporter) .30-06 and 1H (Tropical) .375 H&H Magnum. They are available only through Ruger’s distributor, Lipsey’s (www.lipseys.com). For the foreseeable future, the five No. 1 models will each be chambered in one cartridge every year, but exclusive runs of the rifle will also be made from time to time. “The No. 1 is waning,” Gurney said. One reason is a brisk market for used No. 1s. “People tend to take good care of their No. 1s,” he said.

However, Ruger must keep a few spare No. 1s in a back room. For this report the company loaned me a 1A Light Sporter .243 Winchester. The rifle weighed right at 8 pounds with a Leupold VX-3 2.5-8x 36mm scope on board in Ruger steel rings. The 1A’s 22-inch barrel features a barrel band for a sling swivel. The front sight is also on a barrel band and presents a brass bead for aiming. A quarter-rib holds a fold-down leaf rear sight in a dovetail and bases for connecting Ruger scope rings. Quite a bit of figure ran the length of the rifle’s walnut forearm and buttstock, with contrasting blonde across the buttstock grain. The panels of point-pattern checkering on both sides of the forearm and grip contain fairly well shaped diamonds that provide a sure grip.

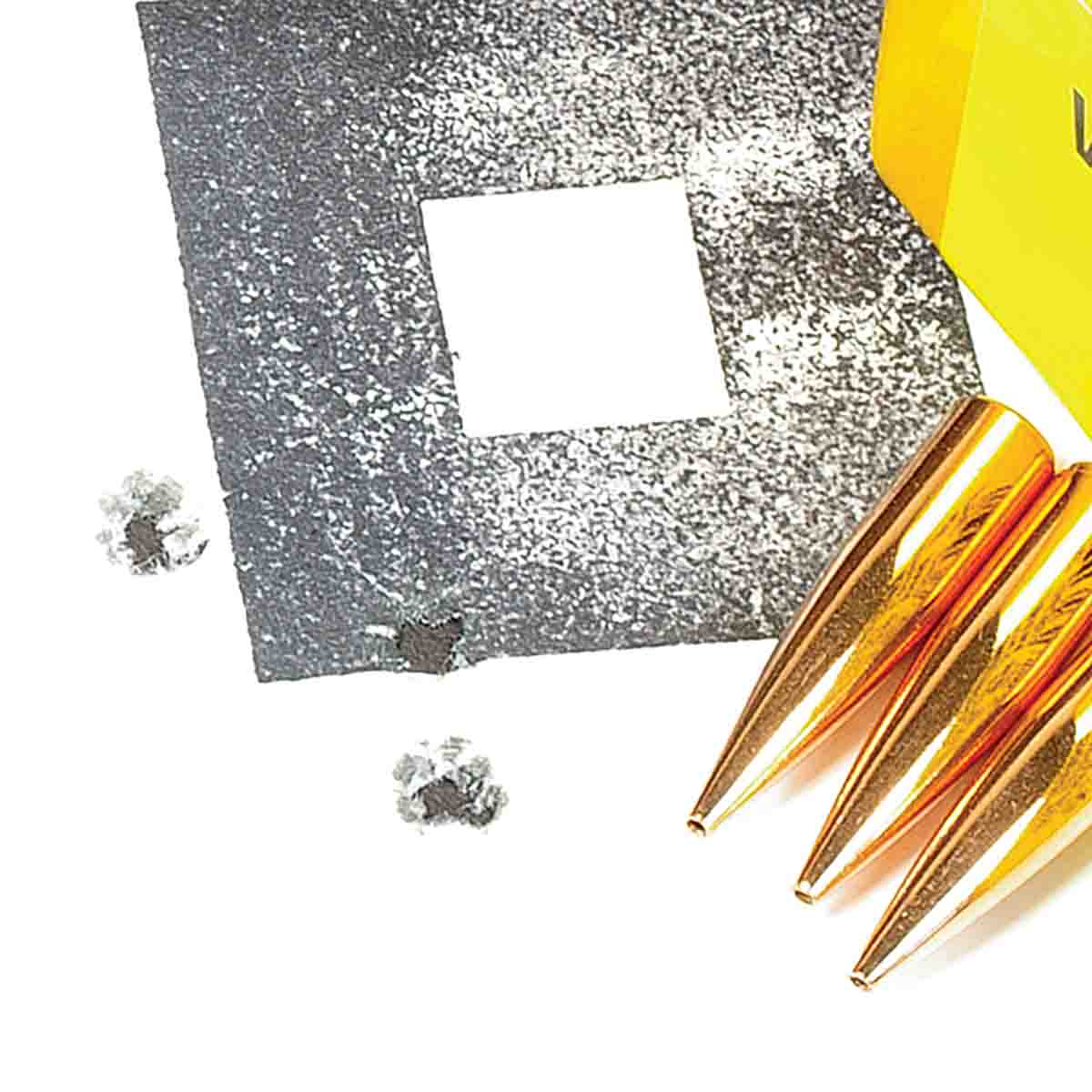

I shot the rifle over several weeks with numerous handloads and one factory load. Horizontal spread of all groups shot at 100 yards was less than an inch. However, the rifle strung its shots vertically 2 inches or more with a few loads. I thought that might have been caused by the receiver extension providing irregular tension of the forearm against the barrel, or that the forearm was too tight against the receiver and pushed against the barrel. Mostly, the reason was handloads that produced wide swings in velocity. For example, Sierra 70-grain Match-Kings had an extreme velocity spread of 136 fps when fired with Benchmark powder and a resulting group of 2.52 inches. The Sierra bullets fired with Accurate 4064, though, had a narrow spread of 40 fps and a 1.05-inch group. Federal Premium Vital-Shok 85-grain Trophy Copper bullets produced a velocity spread of 32 fps and shot a 1.07-inch group.

It was easy to hit patches of snow the size of a soup can at 100 yards shooting the Light Sporter offhand and sitting. A pronghorn antelope at 300 yards would be cinch shooting from prone with the rifle over a backpack.

A minimum amount of effort was required to work the lever to eject a case and chamber a fresh cartridge. I turned the rifle sideways while pushing the lever down to kick out a fired case. Cases either flew out of the chamber or hit the safety tab and fell on the ground. I used to think an ejected case that hit the safety button was a flaw of the No. 1, but Gurney said the safety was designed to stick above the loading channel to stop an ejected case from hitting the shooter in the face.

There is also a fascination and sentimentality to the No. 1. Gurney said he owns quite a few guns but few models of the same gun. “But I do own multiple No. 1s,” he said. When Gurney celebrated his 20th year at Ruger, the company offered him his choice of any Ruger firearm. He could have picked an SR-762 with a price tag of $2,200. Instead he chose a No. 1 .30-06.

Gurney bought another No. 1 purely for sentiment. A few years ago when sorting through Ruger’s Newport archives, he found a note on a No. 1B .270 Winchester that read “Stan – for One Shot Hunt.” He realized the rifle was intended for Stan Terhume to use on the famed One Shot Antelope Hunt in Wyoming that has been held for 75 years. Several people asked Gurney why he’d bought such a plain rifle. “I bought the rifle,” he said, “because Stan hired me in 1994, and he was my idol, because he was a gun guy and a casting guy.”

The No. 1 also stands for stalking within sure distance of game and finishing the hunt with a single shot. One October I guided a fellow from Milwaukee hunting pronghorn antelope on the prairie. Jack was a cheerful guy and completely laid back. It was really no surprise when he pulled a No. 1 .30-06 out of his gun case. During the course of a hunting day, we were in and out of the truck several times. Jack always dropped the lever on his rifle to show the rifle was empty before getting into the truck. When we walked, I noticed he closed the lever but without a cartridge in the chamber.

“You can load your rifle, you know,” I said.

“There’s plenty of time for that,” he replied.

On the third evening, we spotted a real nice buck with thick horns and tips with a deep hook. We stalked up on the buck in the minutes before sundown, but a close look with a binocular showed the bases of the buck’s horns were somewhat short.

“Why don’t you shoot the doe next to the buck,” I said.

“Right,” Jack replied.

In two seconds Jack had chambered a cartridge and lay prone behind the rifle. The shot was easy across a narrow coulee, and the doe fell.

The following day we spotted a buck in the distance. Through a spotting scope it was clear the buck’s horns were outstanding. The buck stayed in the middle of wide open flats and several stalks failed. In late afternoon, the buck and a band of does and smaller bucks lay in the middle of a basin. It was about a 500-yard shot, but Jack said there would be no fun in that.

At sundown the antelope stood and lined out for water. “Jack, this would be a good time to load your rifle,” I said. We stalked up a coulee below a stock water dam. Jack crawled to the crest. The buck stood at the far edge of the water, and Jack shot it. We hurried around the pond to the buck, and its horns were everything Jack had hoped. He ejected the ensuring cartridge from his No. 1. “Just like I had it planned all along,” he said.

.jpg)