.45-70 Cast Bullets

Solid Advice for Hunting and Match Loads

feature By: Mike Venturino | December, 18

The Marlin was okay. Known for its strength, of course I had to try one of Elmer Keith’s .45-70 handloads in it. That was a poor decision, and the first round’s recoil nearly convinced me to give up big bores. That rifle was sold not too long afterward. Conversely, the H&R single shot was a true joy. Whereas the “trapdoor” design is not noted for strength, it was used with more sedate handloads, and I grew to love the old .45-70. That carbine stayed around until I landed an original some years later.

Those experiences began a run that I hope has not ended. Hand-jotted notes show that I have now owned 40 .45-70 rifles and carbines. Plus I have used many more from various manufacturers for use in articles and then returned them. Most of the loaners were leverguns, and most of those purchased were single shots. Collectively, my .45-70 experience has ranged from an original Sharps Model 1874 that factory lettered to Dodge City, Kansas, during the great 1870s bison hunt, to a Japanese-made (Miroku) Model 1886 Winchester imported just a few years back.

I wish notes had been kept on all the .45-70 handloading I have done in the past 46 years. I am sure it would tally over 50,000 rounds. Prior to the advent of the NRA’s

What I can say with some assurance is that about 99 percent of those tens of thousands of .45-70 handloads also included cast bullets, about 99 percent of which I poured. The only jacketed bullets loaded for my .45-70s were used to gather information for articles. The same holds true for commercially-cast bullets used along the way. To perhaps let loose a little ego here, I’ll say that I know my home-poured bullets outclass any that can be bought, both in regard to hunting and target competition.

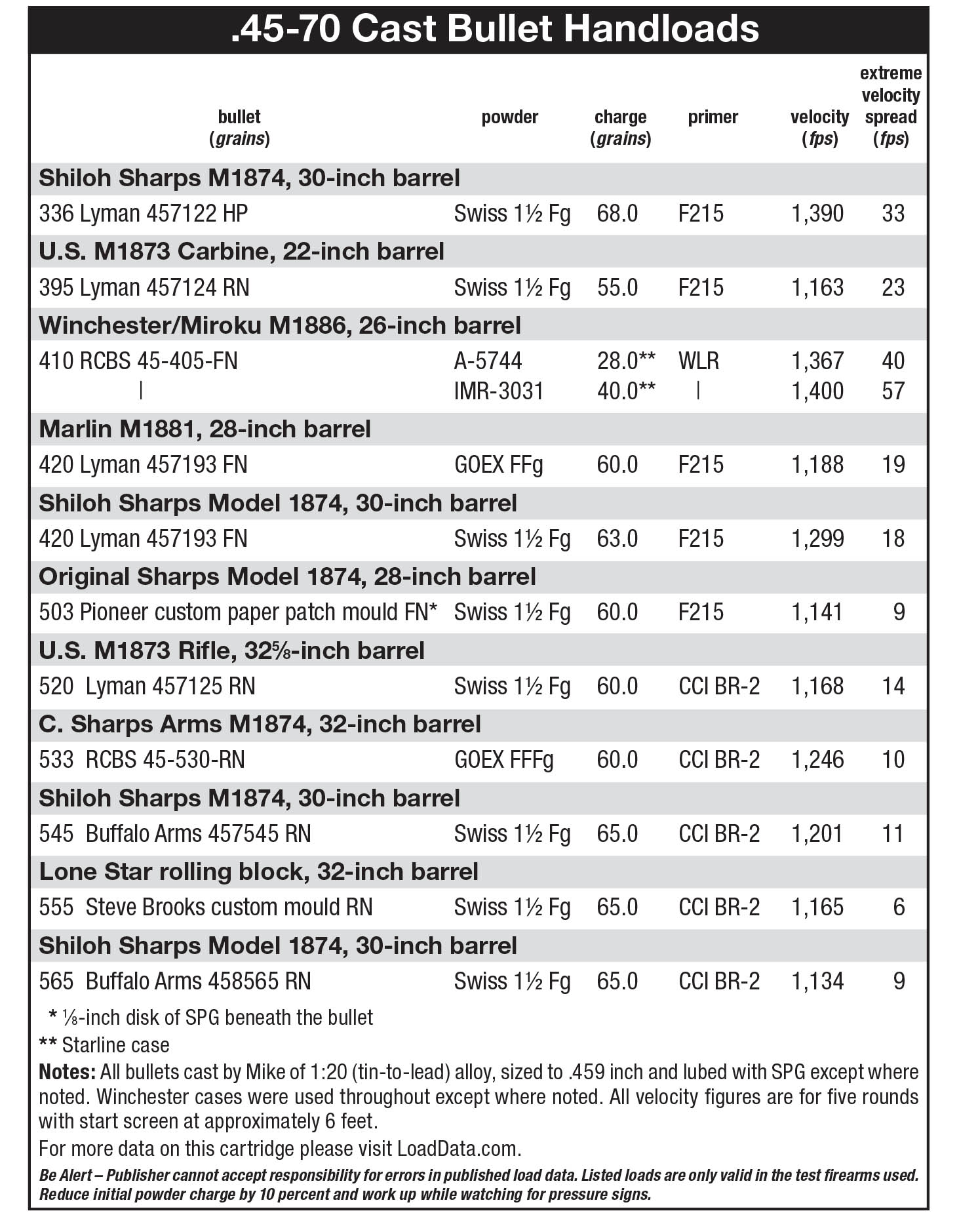

The .45-70 was first introduced as the .45 Government for the army’s new Model 1873 rifles and carbines. Case length was 2.100 inches for use with a 405-grain roundnose lead-alloy bullet of .457-inch diameter. The initial powder charge was 70 grains of black powder. There were complaints of the light carbines giving heavy recoil with that charge, and soon a special carbine load appeared using only 55 grains of powder with the same 405-grain bullet. In 1881 another load appeared for rifle use with a 500-grain bullet over 70 grains of powder. Interestingly, the government chose a 1:22 rifling twist rate. Civilian manufacturers such as Sharps Rifle Company and Winchester tightened that up to a 1:20 twist. Competition shooters today are using 1:16 or 1:18 twists.

My competitive shooting has not been stellar, but it has been thoroughly enjoyable. For instance, I’ve participated in all 32 BPCR Silhouette National Championships. Of those, I finished in the top 10 only three times. A .45-70 was used in each case. In regard to state and regional championships, when I’ve come home with one sort of trophy or another, it has most often been with .45-70s. (I have also shot some dismal scores with .45-70s, but

In all this casting for .45-70s, bullets have weighed from a light 292-grain Lyman No. 457191 to a heavy 565-grain Buffalo Arms No. 458560. Bullet shapes have included flatnose, hollowpoint, spitzer and a variety of roundnose designs. Cast bullet types have included plainbase and gas checked with grease grooves, and cupped base, paper patched designs. I would estimate that at least 100 .45-caliber rifle bullet moulds have passed through my hands – about 20 are still here. My .45-70 bullets have been poured of alloys as soft as pure lead with a Brinell hardness number (BHN) of about 5 to straight Linotype (BHN 22).

Early on I scrounged hundreds of pounds of wheelweights and added just a bit of tin so that the molten alloy perfectly filled every curve and crease inside the mould. The use of wheelweights ceased after becoming a competition shooter, wherein consistency is paramount. A contributing factor was that wheelweights became made of “mystery metals.” With knowledge gained from experience for all .45-70 shooting purposes, I have settled on a blend of 1:20 (tin-to-lead) alloy. BHN is about 8.5. (BHN figures drawn from Lyman Reloading Handbook No. 49.)

At this point someone has to be thinking, What about when .45-70s are handloaded into the lower realm of .458 Winchester Magnum velocities? Don’t they need hard alloys then? My answer is that such loads, regardless of how strong a rifle might be, represent an exercise in futility. A 500-grain 1:20 (tin-to-lead) bullet powered by nothing more than a case full of black powder will deliver about 1,300 fps, depending on powder type and barrel length, and such a load will completely penetrate a bison from about any angle. More velocity merely causes the bullet to make a bigger divot in the ground on the bison’s off side.

Such antics can result in horrendous lead fouling in rifle barrels – much worse than softer bullets. Soft bullets obturate, sealing the powder gases behind their bases. Hard bullets, especially those with bevel bases, allow gas to seep by, and in doing so melt minute particles of alloy onto the rifle’s barrel. As a general rule, my feeling is that softer alloys will only leave friction leading seen as long “strings,” usually in the corner of the rifling. Other times it may be flat pieces (not particles) resting in grooves just ahead of the chamber throat. Such leading is usually caused by lubricant failure.

For .45-70 levergun hunters, the two flatnose bullets mentioned are superlative. Their respective manufacturers list both at 405 grains. From 1:20 alloy, my moulds drop the Lyman at 420 grains and the RCBS bullet at 410 grains. The latter is also a gas-check design that sometimes groups better when smokeless powders are used. Furthermore, both bullets feature crimping grooves placed so that when seated and crimped, overall length is within 2.550 inches.

As to competition bullets for various BPCR games, the options between off-the-shelf moulds and custom moulds must range into the hundreds. I have tried bullet designs as light as 370 grains and as heavy as 565 grains, and have had more success with bullets on the heavy end, say from 530 grains up. The lighter-weight bullets are used for reduced recoil loads when firing offhand at 200 meter chickens.

As to which nose and body shapes are best for .45-70 competition bullets, I long ago decided to let a rifle reveal which bullets it would shoot best. Some shooters like fewer lube grooves so the majority of the bullet is seated outside the case to increase powder capacity. Others want more lube grooves because specific black-powder lubricants help keep fouling soft, and/or they want the bullet seated deeply to reduce powder capacity. Debates abound as to which nose shape is best. Some shooters argue that the U.S. Army did all the .45-70 bullet nose research for them back in the 1870s, so they like the very blunt roundnose used in .45-70 Government 500-grain cartridges starting in 1881. Lyman’s No. 457125 is a close copy, with bullets weighing 520 grains when cast from 1:20 alloy.

From personal observations collected from literally hundreds of BPCR Silhouette matches, the most commonly used .45-70 long-range bullet has the Creedmoor nose. It has a less blunt roundnose that has been copied from original Sharps factory cartridges meant for the famous Creedmoor matches of the 1870s. Right now I have Creedmoor-style bullet mould designs with three, four and five grease grooves and a custom Buffalo Arms four-groove bullet made with a longer, government-style nose. It weighs 565 grains. To be honest, I cannot see where any one of these bullet designs is superior to the others.

With the immense variety of barrel and chamber dimensions found in .45-70 rifles from 1873 to now, it is impossible to specify proper bullet body and nose sizes. An 1870-1880s .45-70 rifle from any manufacturer might have a barrel groove diameter as small as .457 inch and up to .462 inch. Modern .45-70 barrels are usually spot-on at .458 inch in the grooves and .450 inch across the lands. My rule of thumb is to slug the barrel and order a mould that will drop bullets measuring the same as groove diameter to .001 inch larger, and with a nose .001 to .002 inch smaller than the lands. For example, my current Shiloh Sharps Model 1874 .45-70 shoots bullets with a body diameter of .458 inch and a nose diameter of .448 inch cast with 1:20 (tin-to-lead) alloy. Dimensions vary with other alloy blends.

Properly seating cast bullets in cartridge cases is one of the most important steps. Many .45-70 shooters use custom neck expander/belling plugs. I’ve tried several, finding no improvement over Lyman’s .454 diameter plug. Case mouths should be expanded to the minimum amount to allow bullet bases to start freely. They must also be chamfered so lead slivers will not be peeled off during seating.As for crimping, all my smokeless loads, regardless of exact powder, get stout crimps while my black-powder loads get none. A slight exception includes black- powder loads for leverguns, for which case mouths are crimped just enough so a protruding edge doesn’t catch on anything during the cartridge’s travel from a tubular magazine into the chamber.

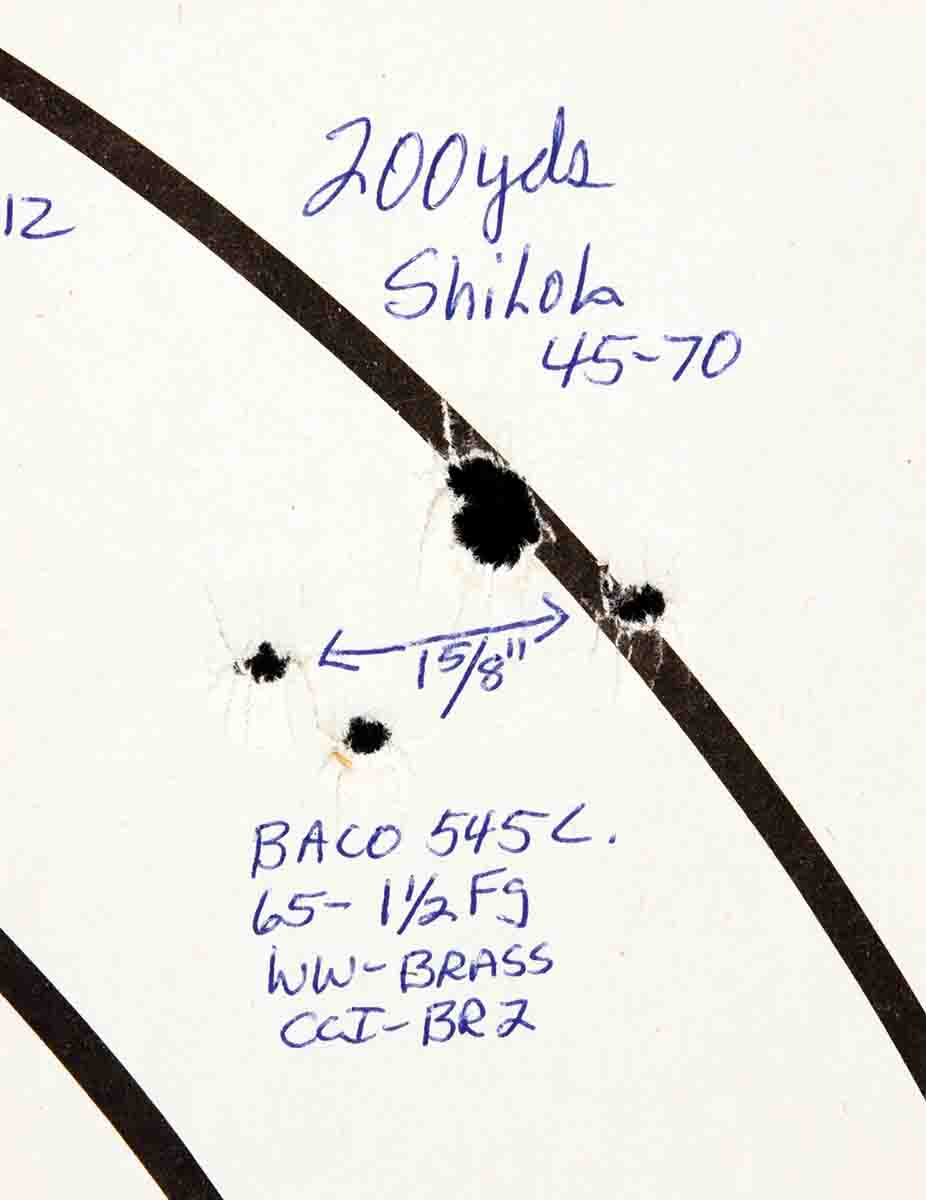

Lastly, what sort of groups should be expected from good .45-70 cast bullet handloads? When firing hunting rifles with open sights at 100 yards, groups of 2 to 3 inches should be expected. A tang-mounted peep sight with a good front sight can better that. With competition grade single-shot .45-70 rifles using carefully tailored handloads, groups of 1½ MOA should be easy under ideal conditions. Never think you are going second-rate by shooting cast bullets in any .45-70 rifle or carbine.