Myths and Misconceptions

Boat-Tail Bullets

feature By: John Barsness | August, 21

Among the subjects often arising on the internet, that twenty-first-century source of information and myth, involves whether boat-tail rifle bullets increase barrel erosion compared to flatbased bullets. Some shooters claim they do, because the tapered boat-tail allows hot-powder gas to slip past the bullet’s base as it enters the rifling. Flatbase bullets form a far firmer gas seal, especially lead-core bullets, since they tend to “bump up” a little in diameter when powder gas boots them in the butt.

Many twenty-first-century shooters claim boat-tails don’t erode chamber throats any faster than flatbases, though few cite specific references involving controlled tests. In one heated internet exchange, three technical books about modern rifle ballistics were cited as “disproving” the boat-tail myth. It just so happened that I had all three books in my firearms library and after essentially rereading all three, the only discussions of boat-tails I found involved their ballistic advantages. Perhaps the folks who cited the books think absence of the erosion issue is proof it doesn’t exist.

I also knew, however, that somewhere in my reading, an “authority” mentioned accelerated erosion, so I started looking through my several hundred books on rifles. Luckily, it showed up quickly in my two-volume reprint of the monthly “Gun Notes” columns Elmer Keith wrote for Guns & Ammo from 1961-1982.

The December 1961, column includes an essay on barrel life. Keith was a member of three Montana or Idaho National Guard rifle teams that competed in the National Matches at Camp Perry, the first two in 1924 and 1925. In fact, Keith joined the Montana National Guard partly because the rifle team would be issued both rifles and ammunition from the Bozeman armory, the closest to his family’s ranch.

The National 1903 Springfield, with an “air-gauged” barrel, was the standard rifle, and in 1924, the then-new National Match ammunition was used. It featured a 179-grain bullet with a 6-degree boat-tail and Hercules Hi-Vel, an early, hot-burning, double-base powder known for being hard on barrels. Team members were allowed to purchase their issued rifles at a discount after the matches, but Keith passed in 1924 and 1925, claiming only 400 shots ruined their barrels for use on the long-range targets.

However, part of the problem was the primer. The early Army priming compounds were at least 40 percent potassium chlorate, which is hydroscopic, attracting atmospheric moisture. This resulted in rusty bores if not cleaned immediately after firing – and cleaning back then required water (preferably hot) to rinse out the potassium chlorate, and “ammonia dope,” a strong ammonia solution to remove copper fouling, which tended to etch bores slightly, like very fine bead-blasting.

Experiments have proven such etching tends to keep hot powder gas in contact with the bore longer, quickly resulting in the cracking of the steel just in front of the chamber often called “alligator skin.” These cracks allow even more hot gas to leak around the bullet, so the primers and cleaning methods tended to shorten barrel life.

“Ammonia dope” was developed due to the extreme fouling resulting from cupronickel bullet jackets made of a combination of copper and nickel. Cupronickel was used for jackets of many early smokeless-powder rifle bullets because it was hard enough to resist deformation, important both in non-expanding bullets, whether military full-metal-jackets or “solids” for hunting very large, big game, and softnose bullets for hunting smaller big game.

Initially, cupronickel left relatively little copper fouling in rifle bores because most smokeless military and commercial cartridges introduced until 1904 produced muzzle velocities around 2,000 feet per second (fps). In 1904, Mauser replaced the original 227-grain roundnose in the 8x57’s military load with a 154-grain spitzer, bumping the velocity up to around 2,800 fps and cupronickel fouling became more of a problem.

The same basic thing happened with U.S. military cartridges. Cupronickel fouling wasn’t a major problem with the 220-grain .30-40 Krag’s bullet at around 2,000 fps, or even when the 1903 Springfield boosted the same bullet to 2,200 fps. In 1906, however, the U.S. military followed Mauser’s lead, replacing the 220-grain roundnose with a 150-grain spitzer at 2,700 fps. Visible lumps of jacket fouling soon built up in the bore, and proved very difficult to remove.

Eventually, this problem was solved by switching to jackets made of gilding metal, a much softer combination of 90 percent copper and 10 percent zinc. However, years of experimentation in production methods took place before gilding-metal jackets became sufficiently hard to hold up to high pressure, especially important with boat-tail bullets.

The faster barrel erosion resulting from the first Springfield boat-tails was in comparison to the 1906 “full metal jacket” spitzers. These actually didn’t have a FMJ, due to the common method of making cup-and-core bullets, swaging a lead core into a cup of jacket material. Softnose bullets are swaged with the core exposed at the front end of the bullet, and flatbase FMJs so the core is exposed at the rear end. Consequently, the 150-grain 1906 bullets really “bumped up” in diameter, sealing the bore tightly against powder gas.

In contrast, full metal jacket boat-tail bullets are swaged with the core inserted in the front end of the jacket, and the sharp tip of the spitzer totally closed. As a result, the jacketed rear end prevents them from bumping up as much as flatbase bullets, especially when compared to exposed core flatbases.

Add hot-burning powders, corrosive primers and strong ammonia cleaning solvents and yes, boat-tails did result in faster bore erosion, which is noted in more than one reference book on the development of the 1903 Springfield and .30-06 military ammunition.

Eventually, non-corrosive primers and gilding-metal jackets helped reduce the erosion problem, but another major step took place in the 1930s, with the development of DuPont IMR-4895, partially for the M1 Garand. IMR-4895 worked so well, the powder remains popular among handloaders today, though it’s now made by General Dynamics Ordnance in Valleyfield, Quebec, Canada, using a formula close to the original DuPont powder.

IMR-4895 burned both cooler and cleaner than previous .30-06 powders, and became the standard both for military and match ammunition, reducing bore erosion and fouling. In the 1940 National Matches, Keith shot on the Idaho National Guard team and noted, “I found my rifle was still very accurate and still in very good shape, owing to the much cooler powder used in the 1940 National Match loadings.”

He doesn’t mention whether he purchased the rifle or not (by then he owned plenty of other rifles to play with), but began the very next paragraph with: “Modern boattail bullets are much harder on rifle barrels than flat-base bullets, for the very good reason that the pushing gas forms a wedge trying to get past the tapered base of the boattail bullet. It does escape past the boattail, as these bullets do not upset to fill the grooves as quickly as flat-base bullets. In so escaping the gas soon burns out the rifle throat.”

This seems to contradict his 1940 results, which were confirmed by tests made at Frankford Arsenal in 1945/46, indicating the accurate life of a typical .30-06 military barrel when used with boat-tail ammunition ran up to around 5,000 rounds. However, once Keith formed an opinion on any subject, he tended to stick to it, often despite evidence to the contrary.

This is exactly why he used 300-grain, cup-and-core Kynoch bullets in his .333 OKH on his first African safari in 1957. He believed in long, heavy bullets at moderate muzzle velocities, no matter their construction. Despite the steel jackets, the Kynoch softnoses blew up like varmint bullets, even on coyote-size Thomson’s gazelles. He finished the safari with Kynoch “solids,” which penetrated well, but the small wound channel didn’t kill larger plains game animals very quickly – the reason he concluded that all African animals were “as tough as an old gum boot.” He could have saved himself considerable trouble by using a .30-06 with 180-grain Nosler Partitions, which had been commercially available for a decade.

A more recent essay on boat-tail erosion was written in 1986 by D.R. Corbin, founder of Corbin Mfg. & Supply, the well-known maker of bullet-swaging dies. He lists several research sources, including Aberdeen Proving Grounds in Maryland and the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

Corbin explained boat-tail barrel erosion with far more detail than Keith: “Since gas pressure acts normal (at 90 degrees) to all surfaces… [this] tends to compress the boattail section of the jacketed bullet inward, peeling it away from the bore and allowing gas to channel its way into the rifling grooves, causing gas cutting of the rifling edges and the edges of the rifling imposed on the bullet. Micro-droplets of melted jacket material can be observed on most boattail bullet jackets along the rifling edges, especially toward the rear of the bullet shank, some large enough to see without a magnifying aid. The flat based bullet tends to compress in length so that the shank is expanded into the rifling, for a superior seal.”

Corbin advocated using a rebated boat-tail design, first developed by Lapua in the 1930s, with a definite “step” at the front of the boat-tail, reducing its diameter slightly. “When the gas reaches the rebated area…it forces the gas to act parallel to the bore rather than at a compressive angle… Internal pressure from the compressed, angled base area then pushes the lead outward, against the inside of the jacket, which in turn seals against the bore more tightly. The peeling-away of the base from the bore is eliminated.”

The rebated boat-tail also theoretically eliminates another problem, the burst of powder gas at the muzzle, which exceeds bullet velocity. With a standard boat-tail bullet, the muzzle gas flows around the outside of the bullet, destabilizing it slightly. This is why short-range benchrest shooters use flatbase bullets: The base deflects the gas to the sides, and the bullet doesn’t wobble as much after leaving the muzzle.

All of this may be why many hunters who rarely shoot groups beyond 100 yards often claim their rifles don’t “like” boat-tails. However, at ranges beyond 200/300 yards, the superior ballistic coefficient of boat-tails reduces wind drift, making them more accurate.

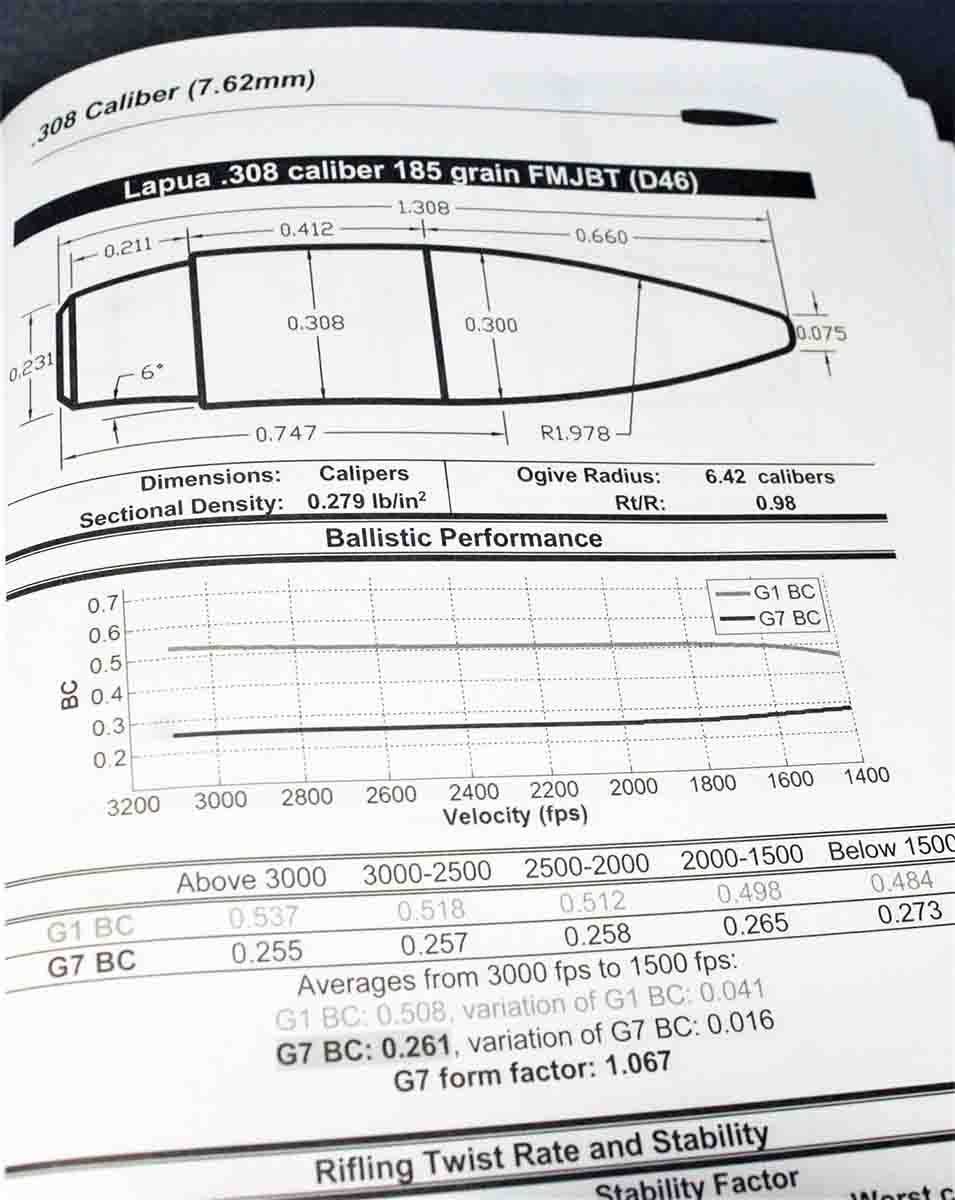

To many shooters, rebated boat-tails would intuitively appear to reduce ballistic coefficient, but Lapua makes 185-grain .308 diameter target bullets in both the rebated D46 and the standard boat-tail Scenar – and lists both the G1 and G7 ballistic coefficients of the D46 bullet as slightly higher than the Scenar. So does Bryan Litz, in his fine book Ballistic Performance of Rifle Bullets, which in my own range testing has provided more accurate ballistic coefficient (BC) information than supplied by some bullet factories. Yet, relatively few rifle bullet manufacturers make rebated boat-tails.

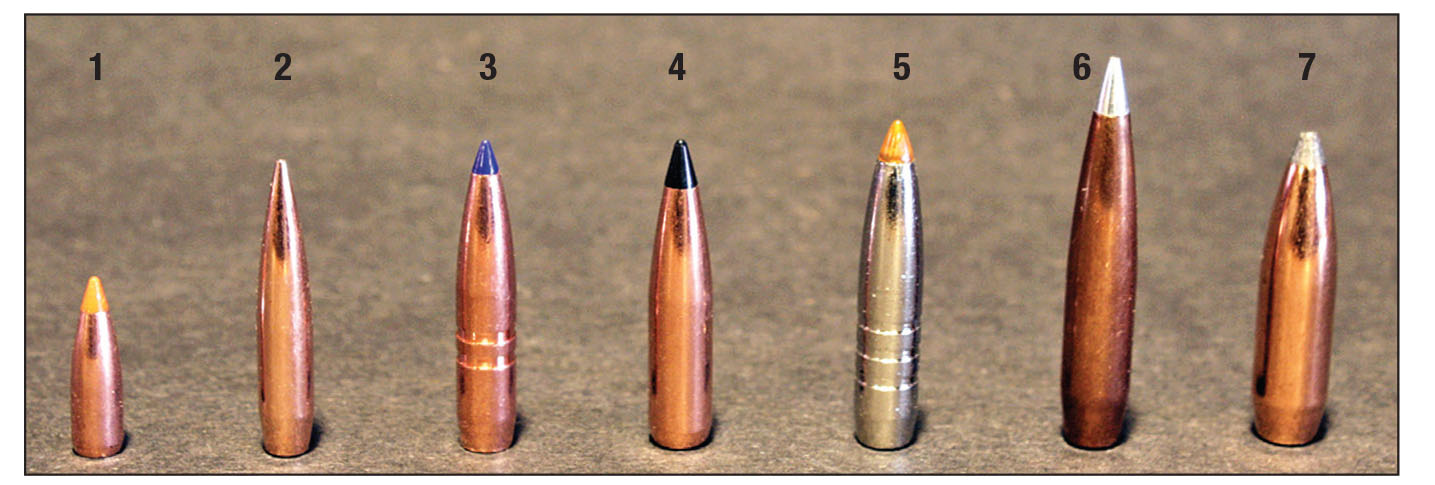

Berger, Hornady and Sierra are all well-known for making both target and hunting boat-tails, but none offers any rebated models. There are probably several reasons, but the biggie is rebated boat-tails are more difficult to manufacture, and hence more expensive. One example appears on the website of Graf & Sons, a well-known seller of handloading supplies: A 500-bullet box of Lapua 185-grain, .30-caliber D46 bullets lists for $535.99, while 500 of the 185-grain .30-caliber Scenars lists for $469.99, 12 percent less. In fact, when I looked through my supply of target bullets there were no rebated boat-tails from any company.

Litz is considered perhaps the preeminent rifle ballistician writing today, partly because he has his own long test range and ballistic lab in Michigan. He disagrees with some of Corbin’s statements in another of his excellent books, Applied Ballistics for the Long-Range Shooter.

Corbin claims “a typical…boattail has from nine to fifteen degrees (measured from the center-line of the bullet) and is about a caliber long. There is no great difference in the performance of any specific angle or length within this general range.” Litz states: “Tests have shown that the optimal angle for boat-tails is around 7-8 degrees.” This is pretty close to the 9 degrees Townsend Whelen arrived at in tests for the U.S. Army over a century ago.

Interestingly, Litz never mentions the supposed barrel-erosion problems of standard boat-tails, perhaps because powders, barrel steels and even boat-tail bullets have improved considerably. One major change in bullets has been the appearance of monolithics, made entirely of copper or gilding metal, such as Barnes X-Bullets. Many monolithics are boat-tails, but because their rear end is too hard for powder to compress it much (if at all), the gas also can’t “peel” the boat-tail away from the bore. I suspect the same thing is true with bullets like the Nosler Ballistic Tip, which features a much thicker jacket/base than typical cup-and-core bullets.

One example might be my old Remington 722 in .257 Roberts that traveled around the family until 1984, when I acquired it for Eileen after she decided to start hunting.

At that time, it had probably been fired less than 300 rounds, since nobody else in the family handloaded, or hunted varmints. I worked up a big-game load with Nosler 100-grain Partitions and a varmint load with 75-grain Sierra hollowpoints, and the rifle groups both well under an inch. Over the next couple decades we put over 1,000 rounds through the .257, and the chamber throat developed some gator hide.

After 2000, it mostly rested in our safe, but a few years ago I decided to take it pronghorn hunting and discovered the somewhat worn barrel refused to group 100-grain Partitions very well. Experimentation with other bullets found the rifle now grouped three shots with the Barnes 100-grain TTSX and Nosler Ballistic Tip about like the original Partition handloads. Is this due to the “hard” boat-tail of both bullets? I suspect so.

I also suspect typical cup-and-core boat-tails still have some effect on bore erosion, but with today’s primers, powders and barrels, the effect is so minimal that tens of thousands of both boat-tail and flatbase bullets would have to be fired through dozens of barrels to arrive at any conclusion. Plus, those shooters lucky enough to burn out plenty of barrels have already “voted” by using plenty of plain old boat-tails, because any difference in barrel life is so small to be inconsequential.

.jpg)