.327 Federal Magnum

Duplicating Factory Loads, Increasing Accuracy and Versatility

feature By: Brian Pearce | October, 20

The .327 Federal Magnum was introduced in 2008 as a joint development between Federal and Ruger. To many shooters a high-velocity, high-pressure .32-caliber magnum cartridge was something of a surprise, and its success was certainly in question. Twelve years later, it has been offered in a variety of guns, including rifles, and it appears to be here to stay.

It was initially offered in the small-framed Ruger SP101 double-action revolver with a 31⁄16-inch barrel as a defensive cartridge that would offer less recoil than larger calibers while producing comparable or greater penetration in ballistic gelatins. It also increased cylinder capacity by one cartridge when compared to the same gun chambered in .38 Special or .357 Magnum. The cartridge has also gained acceptance among sportsmen wanting a flat-shooting, low-recoiling field cartridge, but chambered in revolvers featuring adjustable sights and longer barrels. Through careful handload development, factory load velocities can be duplicated and even exceeded, and accuracy increased. Special purpose handloads will increase the cartridge’s versatility and accuracy while offering substantial savings.

While the .327 is a lengthened .32 H&R Magnum case, which increases powder capacity, it is also loaded to much greater pressures and has some additional engineering features. For example, the .32 H&R has an industry maximum average pressure of 21,000 CUP (Piezoelectric pressure is not established at this time.) while the .327 has a maximum average pressure of 45,000 psi (CUP pressures not established). In order to load this case to such high pressures, it had to be strengthened (or thickened) in the web and in the sidewalls. While I won’t get into too many details, suffice to say that the case metallurgy was changed and is heat-treated to safely withstand the 45,000 psi pressure and permit normal extraction.

During the development of the .327, Federal discovered that many commonly available magnum revolver powders failed to perform as needed. Specifically, it was experiencing high extreme spreads. As a result, it had a special proprietary powder engineered that would reach the desired velocities and help to keep extreme spreads relatively low, which will be discussed further in a moment.

Federal factory loads listed an 85-grain Hydra-Shok bullet (listed as “Low Recoil”) at 1,330 fps, an 85-grain Hydra-Shok at 1,400 fps and the 100-grain American Eagle JSP load was advertised at 1,400 fps, but has now been increased to 1,500 fps. Sister company Speer lists its law enforcement load with a 115-grain Gold Dot HP at 1,300 fps while Buffalo Bore offers jacketed and heavyweight cast bullet loads. Again, handloaders can duplicate or exceed factory load performance.

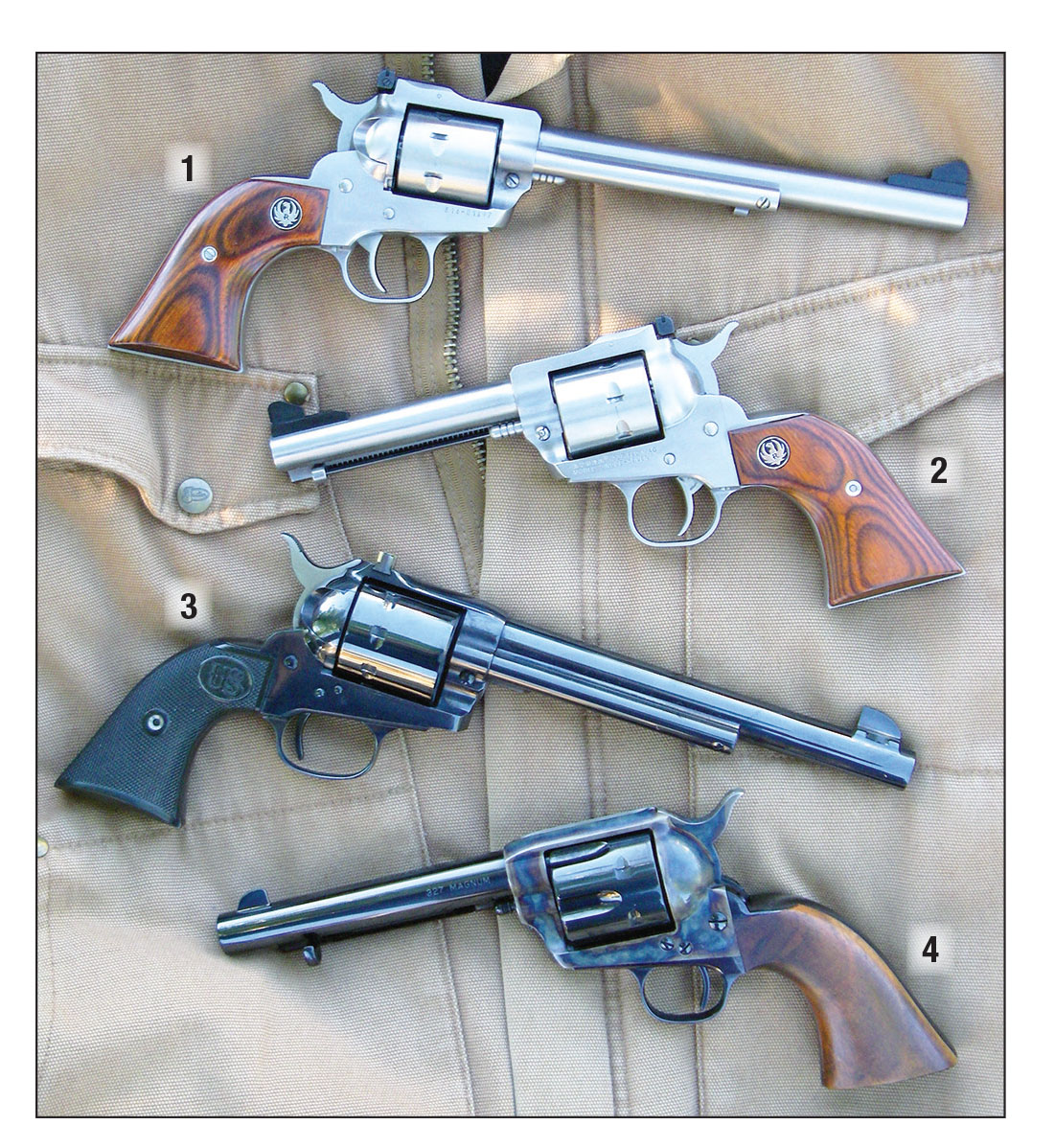

Manufacturers that have offered or are offering revolvers so chambered include Ruger, Freedom Arms, Charter Arms, Smith & Wesson, Taurus and U.S. Fire Arms (USFA); and Henry Repeating Arms offers a lever-action rifle. For developing this data, a Ruger Single-Seven with a 7½-inch barrel was selected. A 45⁄8-inch Single-Seven was used to cross- reference velocities with factory loads. Interestingly, factory loads only showed a slight velocity increase from the 7½-inch revolver versus the 45⁄8-inch gun.

For the record, throat dimensions of both Single-Seven revolvers measured .314 inch, while groove diameter measured around .3125. Ruger specifies a .313-inch groove and .304-inch bore, plus or minus .001 inch. My USFA Sparrow Hawk features .312-inch throats, while a USFA Pre War (probably the only one ever manufactured in .327) has .311-inch throats. Groove diameter for both is .312 inch.

The .32 S&W cartridge (circa 1878), the .32 S&W Long (1902) and the .32 H&R Magnum (1983) can each be fired in guns chambered for the .327. However, due to the long bullet jump, firing the above “short” cartridges in the long .327 chamber generally fails to produce good accuracy.

In thumbing through my correspondence from readers and others, it becomes clear that the .327 has given many handloaders considerable difficulty in producing loads that perform as they should. Some have reported stuck cases with loads that are well below maximum. Others have experienced chambering issues, and many report wild extreme spreads and poor accuracy. I have been handloading the .327 Federal Magnum since it first appeared, developed hundreds of handloads and have consulted with ammunition companies that have struggled with the above issues and used it in more than a dozen guns.

As indicated, cases are constructed of a special brass formula, then heat-treated to handle the 45,000-psi pressures associated with this cartridge. In testing I have found some cases will stick with a given load, while others from the same manufacturer offer normal extraction with the identical load. In at least one instance, cases left the factory without being heat-treated. I have tested recently-produced cases from Speer, Federal and Starline, and all performed properly. It seems that the above issues were mostly associated with early production cases. (Keeping chambers clean will help prevent cases from sticking.)

I recently received a call from a gentleman that was having occasional stuck case issues in his Ruger Single-Seven revolver with loads that were within pressure limits. Most cases extracted easily, but occasionally one would stick severely, and he had to pound the extractor rod with a plastic mallet to eject the case. I suggested that the next time this happens, remove the cylinder and see if the “stuck” case could be removed easily with a fingernail or pushed out using the cylinder base pin. He called me back and stated that the sticky case simply fell out when he removed the cylinder. Next, I had him measure the rim diameter of that case, which was slightly larger than the specified .375 inch. In other words, it was the overly large rim that was hanging up on the loading trough and was not from a high-pressure load. I might add that some of the early Ruger Single-Seven revolvers suffered from a too-small loading trough, which could cause cases to hang-up when being ejected, which again gave the false impression that the loads were producing excessive pressure.

As indicated, Federal had a proprietary powder developed specifically for this cartridge. Unfortunately, it is not offered as a canister-grade powder to handloaders. But with detailed load development and choosing a correct combination of components, handloaders can assemble loads that perform very well and fully equal or exceed factory load accuracy and velocities. (In spite of having access to a proprietary powder, even Federal has struggled with excessive extreme spreads, as early ammunition was recorded with around 200 fps variances for a 10-shot string.)

Incorrect die specification has been a bit of a problem for the .327. For example, carbide sizing dies from several manufactures fail to full-length size the case, even if the die is turned down until it contacts the shell holder. The problem is that the carbide ring has too much bevel or the die body is crimped too far over the carbide ring. In either instance, the die will not fully size the case all the way down to the solid head. This leaves a bulge just forward of the head that sometimes will not allow reloaded cases to re-chamber, or at least they must be pushed into the chamber, all of which is a problem. The best die in this respect is the carbide Lee Precision.

Another problem most dies feature is an excessively large expander ball that often measures around .312 inch and results in an insufficient case-to-bullet fit, or pull. I have lathe-turned expander balls to sizes measuring from .307 inch to .312 and then tested accordingly. Ideally, the ball should measure around .308 to not over .3085 inch, which seems to provide ideal bullet pull with both .312-inch jacketed and .313-inch cast bullets. This snug case-to-bullet fit helps in obtaining proper powder ignition, serves to lower extreme spreads and improves accuracy.

Industry maximum overall cartridge length is 1.475 inches, with almost all loads in the accompanying data being within that limit. The two exceptions included the Rim Rock 100-grain RNFP and Rim Rock 115-grain RNFP with gas check that were seated to 1.498 and 1.485 inches, respectively. Incidentally, the Ruger Single-Seven test revolver only allows a maximum cartridge length of 1.504 inches; however, most other .327 revolvers will accept cartridges with an even longer overall length.

A maximum roll crimp should be applied with all loads, with satisfactory results being obtained with RCBS and Lyman seat/crimp dies. Be careful to avoid over crimping, which can cause damage to the bullet and potentially decrease accuracy. Generally, best results will be obtained if bullets are first seated to the correct overall cartridge length, then as a separate step, the roll crimp applied.

Primer choice is especially important for the .327, which may even be controversial. Federal uses its No. 200 primer in factory ammunition, which is a small pistol magnum primer. I cannot express an opinion in regard to this primer choice used in conjunction with Federal’s proprietary OEM powder, as I have never worked with it. However, I have tried both magnum and standard primers from Federal, Winchester, Remington and CCI with many powder and bullet weight combinations. To keep the primer’s role in perspective, they need to provide proper ignition under all reasonable temperature ranges, and the cup must be strong enough (Note that I did not say “thick” enough.) to withstand the pressures of a given cartridge. Some powder and bullet combinations will show a distinct preference for standard primers, while a few select powders will produce a lower extreme spread with magnum primers. My testing has shown that standard primers usually produce lower extreme spreads, but not always. Even when using maximum charges of slow-burning, magnum revolver powders, the charge weights are usually 14.0 grains or less. These smallish powder charges do not require a magnum primer to obtain proper ignition. Many of the best loads utilize revolver powders with a medium burn rate and only require charge weights of around 6.0 to 9.0 grains. Again, magnum primers are not required to reliably ignite such small charge weights.

For this article, the standard CCI 500 Small Pistol Primer was selected. It offers enough strength to easily handle maximum loads generating 45,000 psi (without piercing or rupturing) and serves to reduce extreme spreads when compared to the same loads ignited with magnum primers. If a magnum primer is substituted with the accompanying data, the impulse time is shortened, pressures will be increased and maximum loads might produce excessive pressures.

Using a standard primer does not magically cure the extreme spread problems associated with the .327. Experimenting is still necessary to find the perfect load. For example, many (but not all) of the starting powder charge weights only gave mediocre accuracy and greater extreme spreads than I would normally be happy with. But as the powder charge was increased, at some point most powders would settle down and produce respectable extreme spreads and good accuracy. Many loads produced their best accuracy with powder charge weights that were in the “middle,” rather than starting or maximum charges.

A good example was observed with Shooters World Heavy Pistol powder with the 115-grain Rim Rock RNFP gas check bullet. The starting charge was 8.5 grains (1,223 fps) and extreme spreads were running nearly 100 fps. As the charge was increased to 10.0 grains, extreme spread dropped to just over 30 fps (outstanding for this cartridge) and velocity was just under 1,400 fps. After bumping the charge to 10.5 and 11.0 grains, extreme spreads increased and gas spitting from the barrel-cylinder gap was notably increased. Several other powder and bullet combinations showed a similar pattern. In extreme instances, velocity actually decreased as the charge weight was increased (those loads being omitted).

.jpg)

Pistol and revolver powders with a medium burn rate, such as Alliant Power Pistol, Hodgdon Longshot, Accurate No. 5 and No. 7, Ramshot True Blue and others, have proven top choices for the .327, as they usually duplicate factory load velocities, produce comparably mild muzzle report and are accurate. Although slower burning, Accurate No. 9 and Alliant 2400 are likewise excellent choices.

Jacketed bullet selection for the .327 is reasonable. The .312-inch 85- and 100-grain Hornady XTP bullets are proven, reliable performers that expand at impact velocities of 800 fps or higher, and they easily withstand the high velocities and pressures associated with maximum loads. Furthermore, they are especially accurate and have given many 25-yard groups that are well below an inch. I have used them many times on rockchucks and other pests, and even managed to take a coyote (with the 7½-inch barreled Single-Seven) at something over 70 yards offhand with the 100-grain XTP pushed to around 1,350 fps using 7.0 grains of Longshot powder. The Speer 100-grain Gold Dot HP is another outstanding bullet that offers consistent performance at all velocities. And being bonded, it holds together in practical mediums, even when pushed to high velocities. Unfortunately, Speer has discontinued (at least as a handloading component) the 115-grain Gold Dot bullet. In the event that readers still have some on hand or find some on dealer’s shelves, load data has been included that duplicates factory load performance.

Swaged lead and cast bullets can perform very well in the .327. The Hornady 90-grain SWC and Speer 98-grain hollowbase wadcutter work well when pushed at 800 to 950 fps. However, due to their soft nature and limited quantity of spray-on lubricants, if pushed to higher velocities they can cause excess barrel leading. Plain-base cast bullets, such as the 95-grain SWC from Redding mould 325, Rim Rock 100-grain RNFP and Hunters Supply 115-grain RNFP that are usually cast at between 14 and 16 BHN, can be pushed to 1,200 fps without leading, and in good barrels can be pushed even faster. For high-velocity loads a gas check is preferred, such as the Rim Rock 115-grain RNFP w/GC. Several powders pushed this bullet to 1,400 fps and up to 1,463 fps. Incidentally, select cast bullet loads produced the lowest extreme spreads of all loads (including factory loads).

The .327 Federal Magnum is a fun, fast and low recoiling cartridge, but it does require testing and experimenting to develop handloads that produce the velocity and accuracy desired by most shooters.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)