Cartridge Board

.310 Cadet

column By: Gil Sengel | October, 20

Students of the rifle know of the Boer War (1899-1902) between Britain and Dutch settlers in South Africa. This little dustup rudely illustrated, to even the dullest British officer, the capability of an accurate rifle when managed by a man skilled in practical marksmanship. Suddenly, marksmanship training, or “musketry instruction,” as it was then called, became a hot topic.

The upshot of this was the birth of the Rifle Club Movement to promote marksmanship in Britain. Two pillars of this endeavor were Lord Roberts and Lord Salisbury, the latter often quoted as saying he “would like to see a rifle in every cottage in the land.” If he could see his country today it would bring tears to his eyes.

Most of Britain was simply too populous for long outdoor rifle ranges. Indoor ranges of 25 to 50 yards were possible, however, and soon appeared in every important town and village. Finding low-powered training rifles then became a problem because in 1900, ammunition production was in flux. Most cartridges, except for military rounds, were still available only as black-powder loadings. Semi-smokeless (a blend of black and smokeless) worked well sometimes but was erosive, and primer compounds then in use rusted bores in a few hours in humid Britain.

Several British rook and rabbit rifles were tried, but they were hunting rifles shot offhand using black-powder cartridges. They fared poorly when fired hundreds of times at a paper target, fouling so badly accuracy degraded unless cleaned frequently. Gunmaker W.W. Greener stated in his book The Gun and Its Development, Ninth Edition, that he was the first English maker to meet this demand for an adequate small bore, short range target rifle. It was built on a scaled-down Martini action and of .310 caliber, the cartridge also being specially designed by him (Greener), and suitable for all ranges from 50 yards to 300 yards. The year was 1901.

Despite Greener’s statement, the .310 Cadet was overpowered for the short-range rifle clubs. It was much more suitable for military training ranges where targets out to 200 yards were available. Thus the word “Cadet” in the cartridge name? The rifle/cartridge combination would also make perfect sense as a training tool for British and Commonwealth troops issued the .577/450 Martini rifle.

Hard facts on the creation of the .310 Cadet cartridge are few. Why it used a heeled, outside-lubed lead bullet (like a .22 rimfire) at this late date is baffling. Retaining this type of bullet in the case has always been a problem since a conventional case mouth crimp can’t be applied. Kynoch rounds use what is called a stab crimp; a small flatnosed punch is pushed into the case a little way behind the mouth, driving metal into the bullet body. It’s hardly an operation that would add to accuracy!

Here we should mention the sometimes noted Australian ammunition using jacketed bullets, but of one diameter of .315 inch. The purpose was home guard use in Australia’s Martini Cadet training rifles in the event the Japanese could not be stopped from invading the country during World War II.

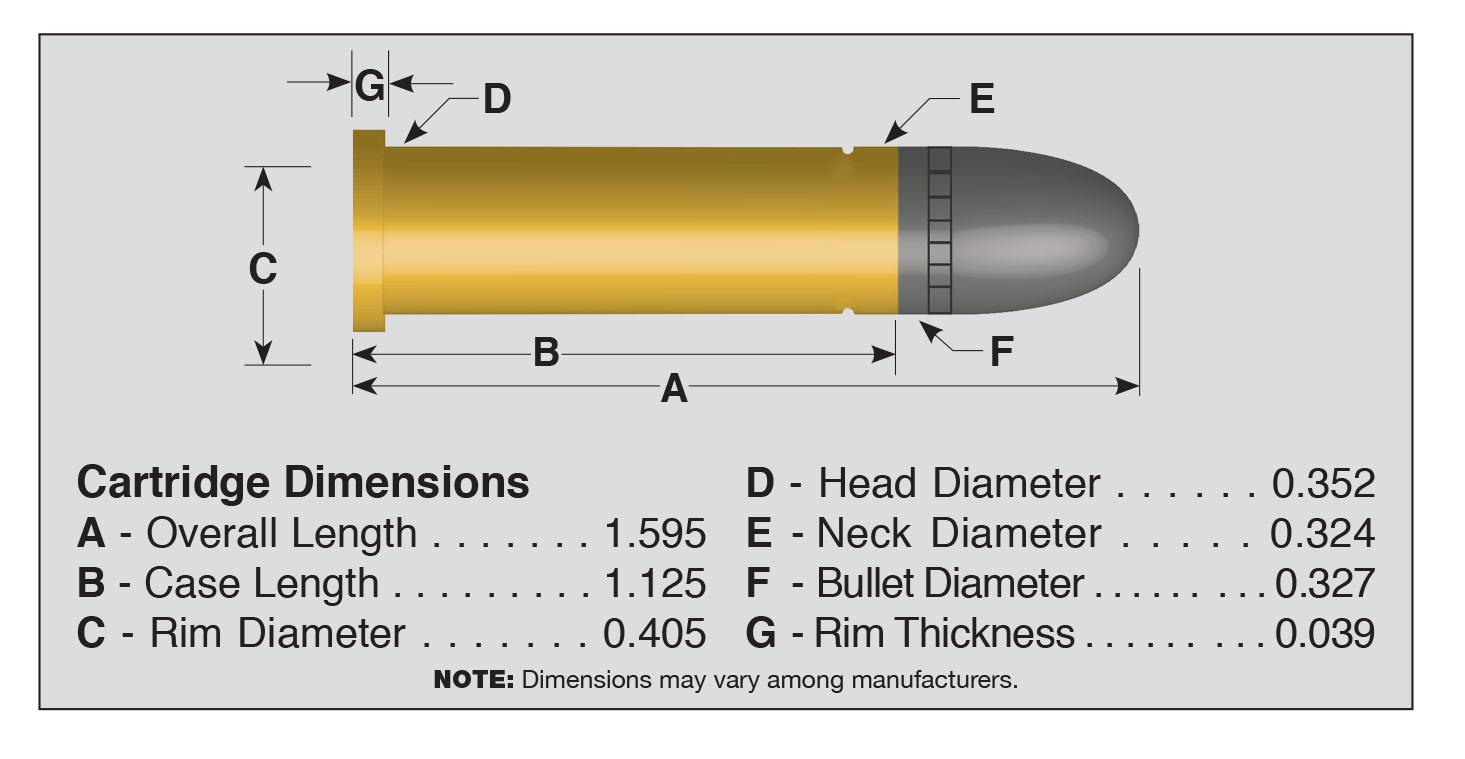

Another mystery is case length. Six references give different case lengths, only one of which equals the 1.125 inches of the Kynoch rounds in my collection. The others are up to .2 inch shorter. Cartridge maker Eley lists five different lengths.

Part of this stems from the existence of a device called Greeners Humane Cattle Killer. Intended for killing animals for meat production or veterinary purposes, it fired a “.310 caliber” cartridge. Design was such that different sizes were required “for killing horses, cattle, sheep, pigs or dogs,” according to Greener, but the cartridge remained “.310 caliber.” Three of the five case lengths listed by Eley are for this device.

References can’t even agree on the type of powder used. Some people insist only smokeless was loaded, but going back to Eley’s list, it shows a .310 Cadet (case length 1.095 inches) in both black and smokeless loadings. There is also a .310 Commonwealth Pattern (case length 1.046 inches) in smokeless only. Nothing could be found regarding what a Commonwealth Pattern might be.

One fact that is not in question is origin of the .310 Cadet case. Despite being “specially designed” (as Greener put it), it is just the .32-20 Winchester, which was then loaded all over the world for use in lever-action rifles. Granted, the case was shortened to allow for the outside lubed bullet, the rim was thinned to prevent chambering a .32-20 and bore dimensions increased to make a .32-20 bullet inaccurate even if the case rim was thinned to fit. Greener was a very smart guy when it came to firearms. What he created was such a screwed-up thing from an ammunition standpoint that no one would have considered handloading fired cases. Given the multiple case lengths and heeled bullet, few foreign ammunition makers would have been interested either. Only the British trade would supply cartridges. What a coincidence.

Factory cartridges were available using a 120- to 125-grain lead roundnose at 1,200 to 1,320 fps, the same bullet with a tiny hollowpoint at the same velocity and an 84-grain lead hollowpoint with no velocity data given. The 84-grain hollowpoint was reportedly not very accurate.

Speaking of bullets, another of the .310 Cadet’s mysteries is bullet diameter. References vary from .316 to .328 inch. The largest figures were obviously obtained by measuring the exposed driving surface of a loaded round and thus include dried bullet lube. The cartridge drawing with this article is from an unhandled Kynoch round; cartridges showing more wear are smaller. Since bullets were dip-lubed, thickness of the lube coating varies.

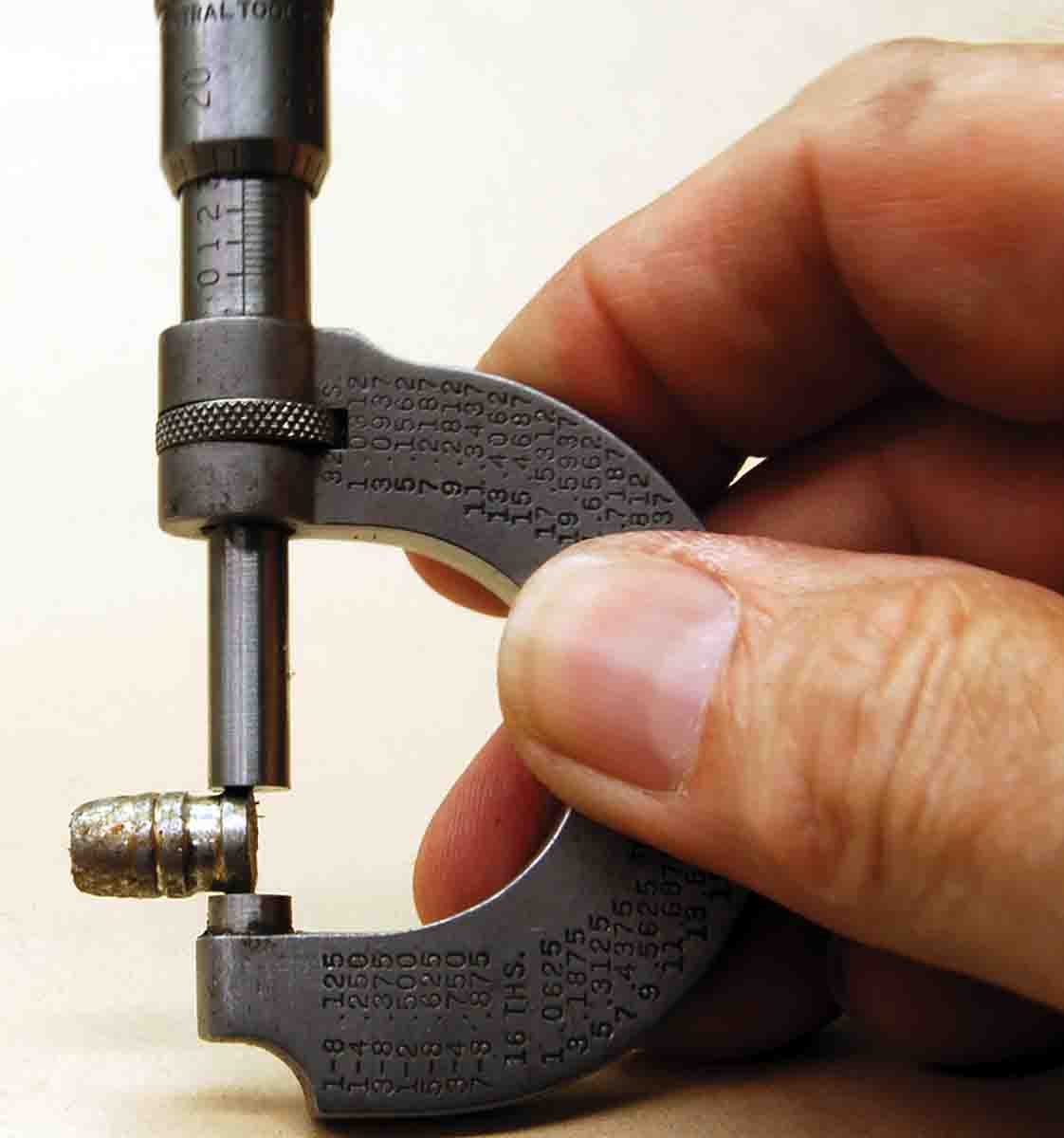

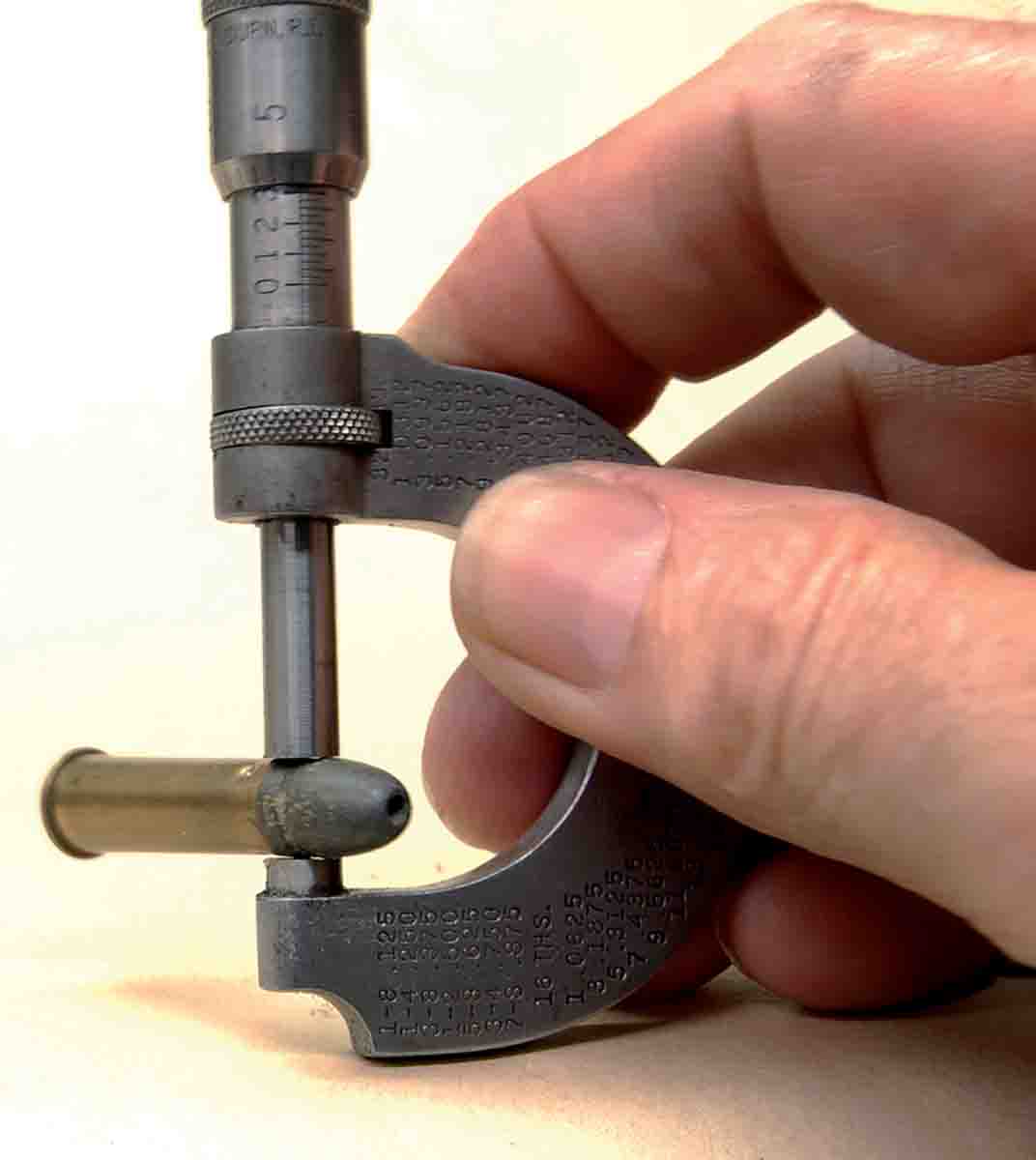

The only way to determine proper bullet diameter for a rifle is to slug the bore. This was done to the rifle shown, which has what appears to be a perfect bore. Bore diameter was measured, using plug gauges, at exactly .310 inch. Grooves are .3180 to .3184 inch.

The .310 Cadet would have disappeared if it hadn’t been for Australia buying thousands of the little Martinis for use as training rifles. They became available on the surplus market in the U.S. in the 1950s. Most were disassembled for their neat little actions, but a few were unaltered or rechambered to .32-20, which just deepened the rim cut, allowing that cartridge to be fired. Accuracy was poor due to the small diameter bullet.

Many owners would like to handload for their rifles. Proper cases, special bullets and even custom ammunition are sometimes seen on the internet. RCBS offers a heeled bullet mould, but because of the COVID-19 foolishness, I could not obtain one in time to try it. Some Lyman 313493 bullets were cast in an ancient mould that came out .317 inch in diameter, with a weight of 106 grains. These were loaded in unfired Starline .32-20 cases after the rims were thinned.

As the accompanying table indicates, accuracy was not very good. Some of this is due to the bullet, but a lot is the chamber throat, which like most British rook rifles, is just a tapered hole from somewhere in the chamber to somewhere down the bore. It is unbelievable. A target rifle cartridge?

The .310 Cadet is definitely a graduate school project for handloaders. Too bad it wasn’t designed using the .32-20 case firing a special target bullet in a proper chamber with matching rifling twist. It could still be popular today.

.jpg)