Through careful handloading techniques and using proven load recipes, handloaded ammunition can be perfectly reliable in the 380 ACP.

The 380 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP) was designed by John Browning and formally introduced in 1908 along with the Colt Pocket Automatic Pistol. However, it was not introduced to Europe until around 1912.

In the past 115 years, its success around the world has been remarkable. It has been chambered in a variety of pistols, both foreign and domestic, and although it was officially adopted by several European countries for military use (prior to World War II) and found favor with officers using the Walther PPK pistol, its primary role has been in personal defense applications. But for the majority of its life, factory loads have been lacking in many respects, as they generally featured a 95-grain full metal jacket (FMJ) roundnose-style bullet that produced little shock or tissue damage. However, today’s factory ammunition has been vastly improved with loads designed specifically for defensive purposes. There are also many relatively new compact, lightweight pistols that have been introduced that are reliable and have gained widespread acceptance for concealed carry applications.

To cross-reference 380 ACP handloads for function and reliability, Brian used (top to bottom): a Ruger LCP, a Walther PPK/S and a Kel-Tec P3AT.

This combination has rapidly elevated the popularity of the little 380 to higher levels than at any time in its history. While it seems almost humorous, this explosion in popularity literally caused ammunition shortages, as the industry was not prepared for such a huge upswing. But ammunition companies have now, at least for the most part, added the necessary capacity to meet demand. Nonetheless, having dies and components on hand, along with proven handload recipes and the knowledge of how to assemble top-drawer ammunition may become important considering our seemingly endless turbulent political climate.

Due to the many different pistols in circulation, many of which are imported, it seems prudent to mention some of the other names for the 380. In the U.S., it is generally referred to as 380 ACP or 380 Auto, but in Europe and other parts of the world, it is known as the 9x17mm, 9mm Browning, 9mm Corto, 9mm Kurz, 9mm Short, 9mm Browning Court, which is Europe’s CIP official designation. The 380 ACP should not be confused with the 38 ACP – the latter being the predecessor to the 38 Super, which is more or less externally the same, but loaded to greater pressures and velocities.

While my love for big-bore sixguns is a poorly kept secret, I have tested and experimented with many 380 pistols and developed data, some of which has been used by select ammunition companies. One problem with some vintage pistols is that they fail to feed many hollowpoint bullets with 100 percent reliability. In these instances wherein a classic pistol is being used, handloaders will do well to use traditional 95- to 100-grain FMJ roundnose bullets pushed to 900 to 1,000 feet per second (fps). If barrel wear is of concern, roundnose cast bullets can be employed that offer minimal barrel wear (with data included herein), but I am getting ahead of myself.

The 380 ACP (left) is notably smaller and shorter than the 9mm Luger (right), which limits suitable bullet weights and powder

Another ammunition or case problem that has been observed is variations in rim dimensions and the width and depth of the extractor groove cutout. This variance has been observed with domestically produced and foreign-produced cases. When cases are out of the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) specifications, they can cause reliability issues with guns that otherwise function more or less perfectly. Plus, I have seen vintage guns originally produced for foreign trade and corresponding European ammunition that fail to function with modern U.S. specification ammunition. For today’s purposes, new Starline cases were used to develop the accompanying data that corresponded perfectly with several modern test pistols that were used to cross-reference function and reliability.

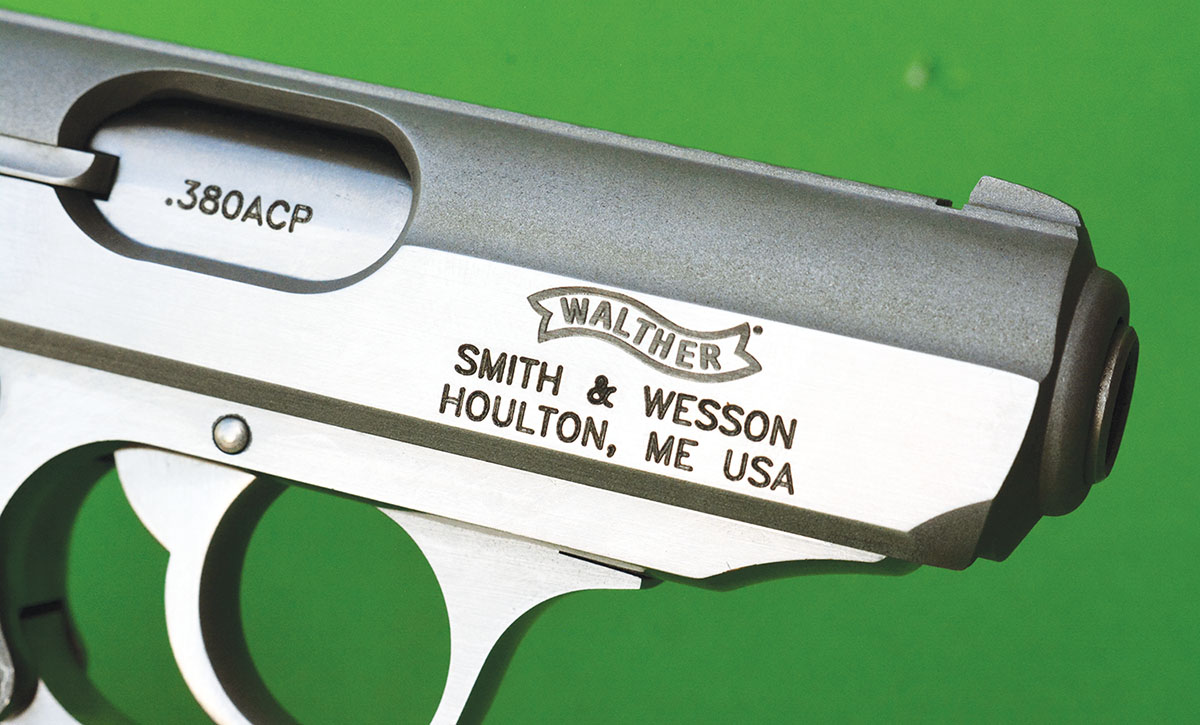

A Smith & Wesson manufactured Walther PPK/S chambered in 380 ACP was the primary pistol used to develop “Pet Loads” data.

While pressure guidelines have varied over the past 115 years, currently the 380 is listed by SAAMI with a maximum average pressure of 21,500 psi or 17,000 CUP. Traditional U.S. factory loads have pushed a 95-grain FMJ roundnose bullet at around 955 fps, however, in pressure tests, those loads are generally below industry maximum pressure guidelines. This conservative approach is probably due to early pistols that are still in circulation. However, when handloading for modern pistols, pressures and performance can often be increased when compared to factory loads, but loads should still be held to the industry standard pressure of 21,500 psi. Most of the accompanying data has been pressure tested and is within those pressure limits. Data should be used exactly as shown, as component substitutions can cause pressures to increase. It is especially important to seat bullets to the specified overall cartridge length. In essence, by seating bullets deeper than specified, even as little as .010 to .050 inch, pressures can rise substantially.

The maximum 380 ACP case length is .680 inch, while the suggested trim-to length is .675 inch.

After bullets are seated to the correct overall cartridge length, a taper crimp should be applied, which is generally best to be accomplished as a separate step. The crimp should measure no larger than .373 inch, but the accompanying “Pet Loads” data was crimped to .370 inch. For reference, several factory loads were measured that ran from .369 to .373 inch. The crimp is especially important as it serves to hold the bullet in place while the cartridge is being fed, but the case mouth serves to provide positive headspace control and must correspond with the chamber of the pistol. It should also be noted that there are variations in case thickness (by brand) that may require slight changes in crimp dimensions, however, generally .370 to .372 inch will be the targeted dimension.

Like other straight-walled (rimless) cartridge designs, carbide dies are highly recommended to eliminate the need for case lube, which saves time and hurries the handloading process along. When sizing cases, be certain that the die is properly adjusted to remove the bulge that can appear just forward of the case head, but (depending on individual sizing die design) the shellholder should not contact the carbide ring, which can cause it to break. If the carbide ring is “protected” or countersunk into the steel die body, the die can contact the shellholder and will not damage the carbide ring. However, some carbide rings are flush with the bottom of the die. In these instances, placing a .001-inch feeler gauge between the die and the shellholder as the die is being adjusted (down towards the shellholder) will serve to prevent breakage and allow the case to be full-length sized. RCBS dies were used to assemble the accompanying “Pet Loads” data.

Most 380 ACP pistols function reliably with ammunition that is around .960 inch. However, the overall cartridge length should never exceed .980 inch.

I have several reference dies from different manufacturers. It should be noted that after the case mouth is expanded, the sized portion of the case body that contacts the seated bullet is very short. This limits bullet pull, or case and bullet tension. For these reasons, I suggest that the expander ball measure no larger than .352 inch and .351 inch is preferred. Also, be careful to not expand the case mouth more than is absolutely necessary, which should be just enough to allow the bullet to be held by the case and “start” into the case while being seated.

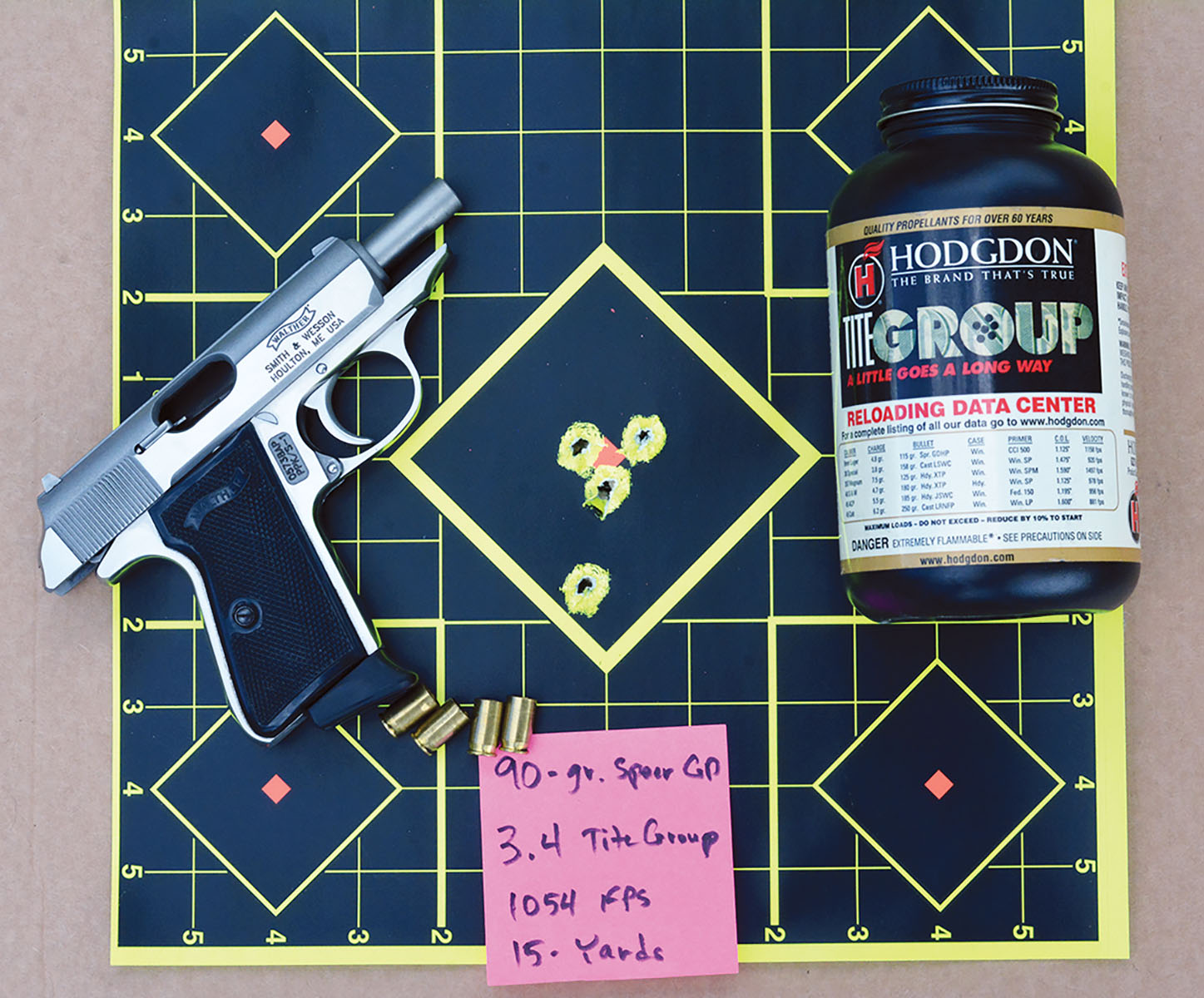

The primary 380 test pistol was a (stainless steel) Walther PPK/S that was manufactured under license of Carl Walther by Smith & Wesson. It features a 3¼-inch barrel and has been reliable with a variety of loads. The front sight is fixed, but the rear sight is drift adjustable for windage to allow sighting-in. Plus, the sight picture is good, which was necessary to evaluate accuracy potential of various loads. Many of the handloads were cross-referenced in a Ruger LCP, a Kel-Tec P3AT and a Browning BDA-380, which was primarily to establish proper function in a variety of pistols.

Most factory-loaded 380 ACP ammunition features a crimp that is .369 to .373 inch. Brian applied a taper crimped to “Pet Loads” data that measured .370 to .371 inch, which proved 100 percent reliable in the test pistols and provided positive headspace control.

It should be noted that many 380 pistols feature a very short action length that limits what loads will function with complete reliability. Loads with too little pressure may not have enough energy to fully cycle the action, while loads that are near maximum can even cause reliability issues due to the speed that the action works and can hang up on empty cases before they are fully ejected. I have seen both of the above problems with factory loads. In other words, some high-quality factory loads are perfectly reliable in one pistol, but less than reliable in others. On the other hand, those same pistols that are less reliable with a given load can work perfectly with a different load. With that thought in mind, it is suggested to experiment with bullet type, powder type, charge weight and velocity in a given gun to determine what load it favors for reliability, especially prior to loading up a quantity of ammunition. That said, load data that pushes 90-, 95- and 100-grain bullets at between 850 to 950 fps will generally cycle in most pistols.

Like the 9mm Luger, the 380 utilizes .355-inch bullets. However, due to its shorter overall length, shorter case length and reduced powder capacity, it requires lighter-weight bullets. If expansion is desired, generally 90-grain bullets or lighter should be used to reach a high enough velocity to allow bullets to expand reliably. Achieving reliable expansion has plagued the 380 since the introduction of jacketed hollowpoint-style bullets; however, new technology has substantially improved bullet performance. For example, the Cutting Edge 75-grain Raptor features solid copper construction, but with a large hollowpoint with precut petals that readily peel back upon impact and due to its light weight, it was easily pushed to more than 1,100 fps. The Barnes 80-grain TAC-XP bullet reached more than 1,050 fps and is likewise designed to expand at 380 velocities. A more traditional cup-and-core jacketed bullet includes the Hornady 90-grain XTP that the factory stated will expand reliably at 800 fps, but was easily pushed to around 1,050 fps with many different powders. The Speer 90-grain Gold Dot HP offers a bonded design that expands at speeds as low as 800 fps, but again easily reached more than 1,050 fps with several powders. Some tests were conducted with 115-grain JHP bullets designed for the 9mm Luger, but their low velocities limits performance and they failed to expand. Their use in the 380 is not generally recommended.

Due to the very small powder charges associated with the 380 ACP, an accurate scale is important and a powder measure designed to throw such tiny charges such as the Redding Competition 10X (not shown) is highly recommended.

The effectiveness of the Sierra 95-grain FMJ features a flatnose and the Winchester 95-grain FMJ (FN) should not be overlooked for self-defense purposes. Being an old handgun hunter, I understand the value of flatnose (meplat) bullets, as they create impressive wound channels, deliver shock to the nervous system and offer notably better penetration than comparable JHP bullets, and unlike many roundnose bullets, they usually offer arrow-straight penetration.

For those wanting to more or less duplicate traditional roundnose factory loads, Speer offers a 95-grain TMJ roundnose (not available at press time, but it can be used with Sierra 95-grain FMJ and Winchester 95-grain FMJ (FN) data). Hornady offers a 100- grain FMJ roundnose bullet that cycled in all test pistols without any issues.

Cast bullets were sized to .356 inch and included the Missouri 95-grain roundnose, the Rim Rock 100-grain Top Shelf flatpoint and the Lyman 121-grain No. 356242, all producing respectable accuracy. It should be noted that the Lyman 121-grain bullet reached between 850 to 900 fps, however, being lead-based, there was no concern of sticking a bullet in the bore, but suggested start loads should not be reduced. By comparison, 115- and 124-grain jacketed bullets gave a much lower velocities with maximum loads and due to their greater resistance in the bore, there was concern that they might stick in the bore, which further explains why they were omitted from the data.

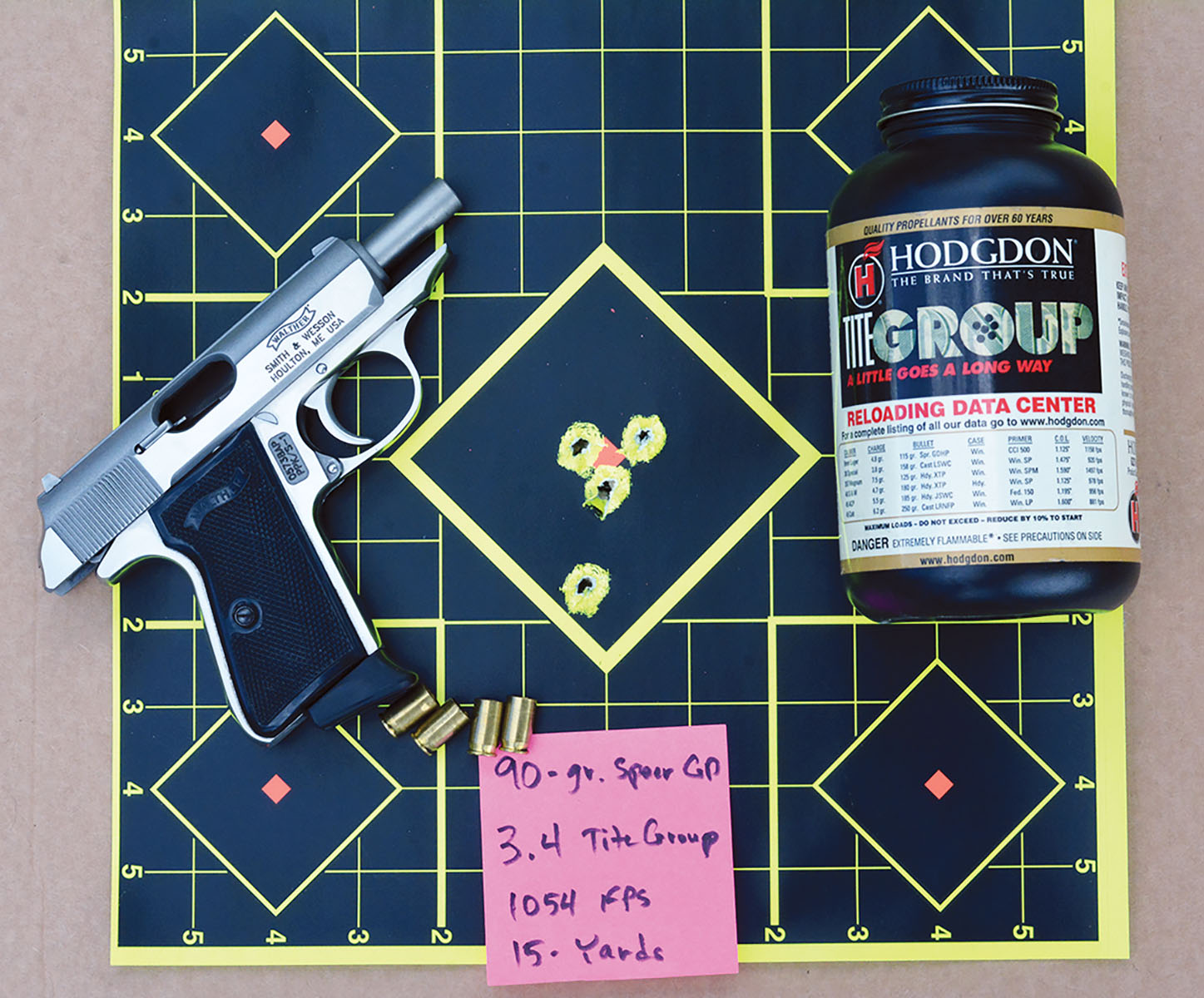

Choosing top-performing powders is very difficult, as all the loads in the accompanying “Pet Loads” data performed very well in terms of velocity, low extreme spreads, accuracy and reliability. However, some powders consistently gave higher velocities (if desired) while staying within pressure guidelines. Those included Winchester W-231, AUTOCOMP, W-244, W-572, Accurate No. 2, No. 7, Alliant Unique, Power Pistol, Hodgdon Titegroup, Longshot, Universal, CFE Pistol and Vihtavuori N-330. For the high-volume shooter desiring clean-burning propellants, Hodgdon Titegroup, CFE Pistol, Accurate No. 2, Alliant BE-86, Red Dot, Sport Pistol, Winchester W-231, AUTOCOMP, W-244 and others will be good choices.

While the 380 ACP is primarily used for defensive applications, accuracy can be respectable.

It should be noted that due to the 380’s tiny size, it is critical to precisely throw powder charge weights. Naturally, a high-quality scale will be important, which should be carefully checked and calibrated for accuracy. But a powder measure designed specifically to throw small charge weights will play a huge role in assembling consistent ammunition. A Redding Competition 10X powder measure was selected to aid with developing the “Pet Loads” data. The Competition 10X offers outstanding uniformity and generally throws accurate charges ranging from 1 grain (or less) up to 25 grains (depending on powder type). It should be noted that spherical (aka Ball) powders generally meter more precisely than extruded (including flake) powders, which is an advantage when handloading such a tiny cartridge.

As indicated, most 380 pistols are designed primarily for personal defense purposes and accuracy is not the focus. However, in a quality pistol, accuracy can be fairly good. Years ago, I had a pre-World War II vintage Walther PPK pistol that was capable of sub-2-inch groups at 20 yards, which is respectable and it could have served as a small-game gun in a pinch. But being in pristine condition and in its original box, it was better off being sold to a collector who would protect it from a shooter and ruffian like me!

With new guns, new powders and new bullets, the 380’s performance is better now than at any time in its 115-year history.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)