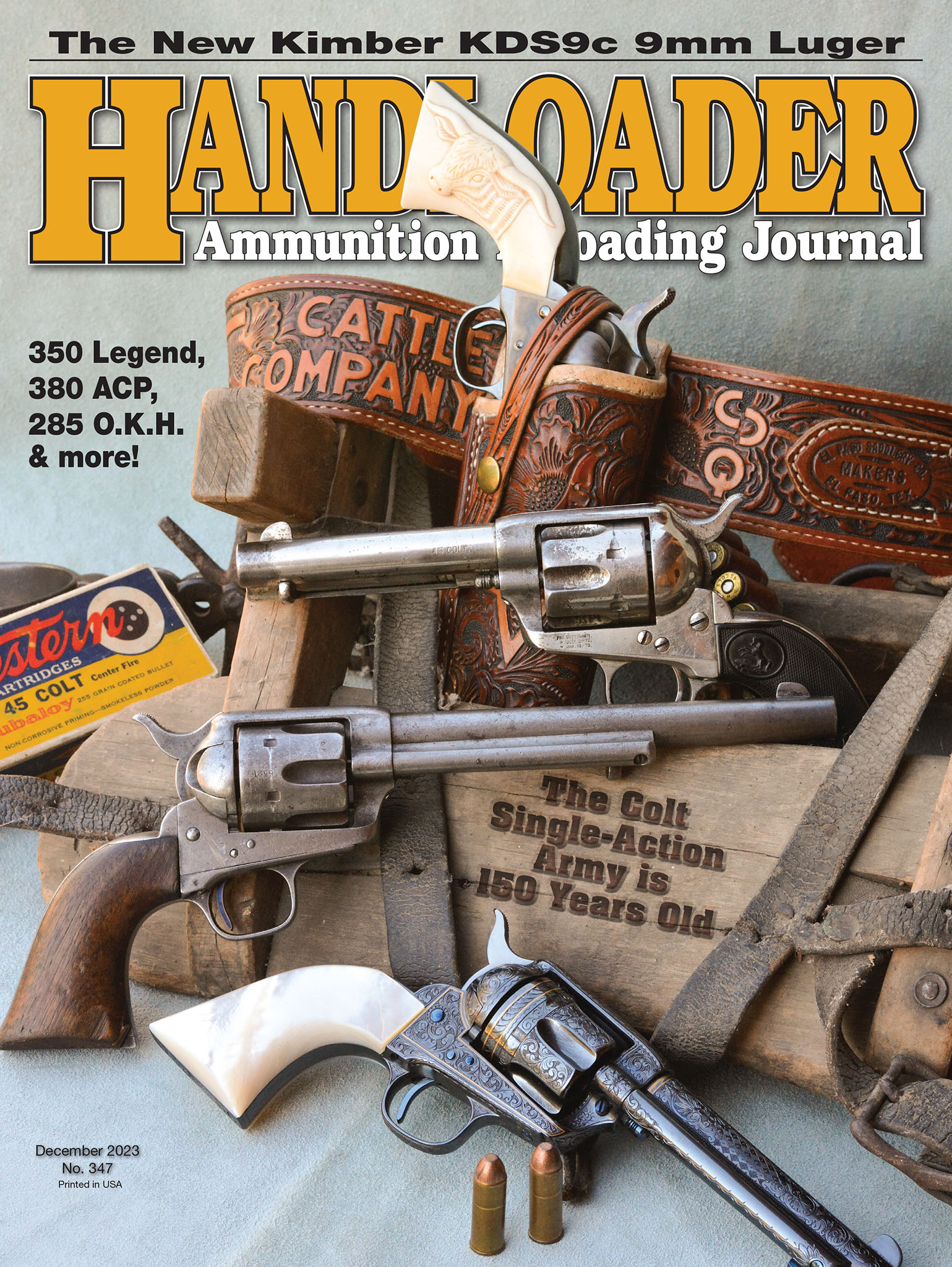

Handloading U.S. Military Handgun Cartridges

Duplicating Original Loads

feature By: Mike Venturino - Photos by Yvonne Venturino | December, 23

Like just about every American who grew up during the 1950s/1960s, I watched westerns that appeared on television and in movie theaters. My all-time favorites were those that dealt with U.S. Cavalry in the Plains Indian Wars through the early 1940s when American horse soldiers fought the Japanese in the Philippines. In my teens, I began seriously studying the actual fights that involved American horse soldiers. Their influence was so great that at age 19, I filled my sister’s VW Beetle with camping gear and traveled westward to see some actual battle sites in person. I visited places such as Wounded Knee, Fort Phil Kearny, the Wagon Box Fight, Fetterman’s Massacre and topped it off by visiting the field of the greatest western battle with Indians – the Little Bighorn.

With such enthusiasm, it is little wonder that as a shooter and handloader, the firearms carried by cavalry troopers also became a study for me. A total of six basic metallic cartridges were adopted by the U.S. Army for cavalry service. There was a later 45 Colt variation along with an odd experimental single shot, but I have no experience with the latter cartridge.

For those cartridges, six revolvers and one semiauto were adopted between 1870 and 1911, excluding the single-shot 50 Remington Rolling Block pistol and others tried in field trials. Of those I’ve owned, five originals albeit two were commercial samples; identical in all respects to the military issue but lacking martial markings. Also owned have been several modern-made replicas. The single original that never fell into my hands for shooting was a U.S.-marked Colt Single Action Army 45. Collector demand kept its prices higher than my finances. As will be shown later, a fine substitute is part of my current collection.

Smith & Wesson 44 AMERICAN (44/100 )

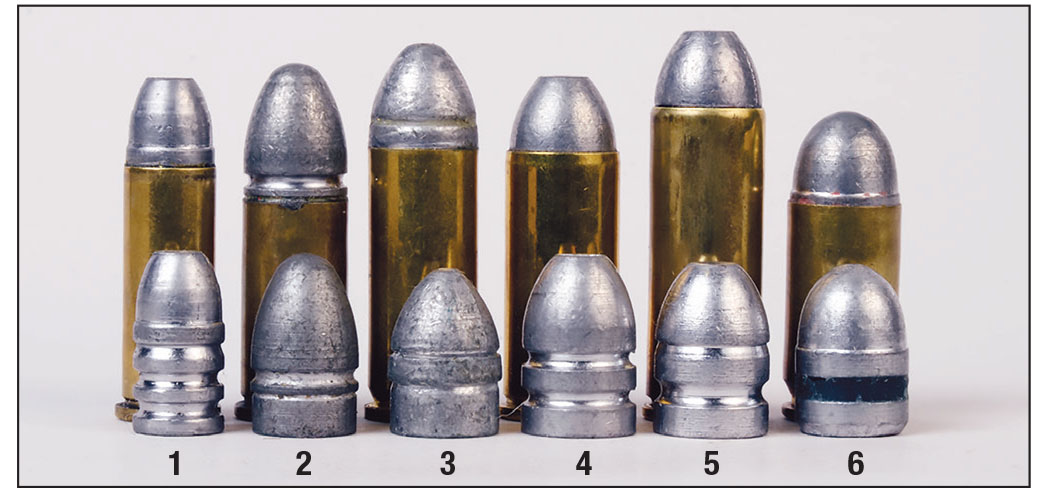

In May 1870, Smith & Wesson completed its Model No. 3 top-break revolver that was initially chambered for the 44 Henry Rimfire. It was submitted to the U.S. Army’s Ordnance Board, whose sitting officers liked the revolver itself, but not its rimfire cartridge. S&W then essentially only converted the 44 rimfire to centerfire. At first, its name was simply 44/100. The case length was .91 inch with a black-powder charge listed from 23 to 25 grains under bullets of 205 to 218 grains. The government gave S&W a contract for 1,000 of the new Model No. 3 revolvers with 800 having blue finish and 200 were nickel plated. The idea was to determine which finish best fit hard field use. All had 8-inch barrel lengths. That first lot of 44/100s was delivered by March 1871. The bullet diameter according to Cartridges of the World 6th Edition lists bullet diameter as .434 inch for the heel-base-style bullet. How did the name 44/100 segue to 44 American? By 1872, Smith & Wesson was selling No. 3 revolvers to the Russian government but the latter insisted on its own cartridge design. It was named the 44 Russian. Thus the 44/100 became 44 American.

My S&W No 3 44 American did not bear martial markings. Instead, it had been shipped to a New York City dealer in July 1873. Otherwise, it was identical to the military version. For handloading, I shortened 41 Magnum cases to .91 inch. At that time, RCBS sold both reloading dies, case forming dies and a bullet mould. All were special order items. (Note that RCBS does not accept special orders anymore.) As best I can determine, the velocity of military 44 American loads was around 700 feet per second (fps) give or take 25 fps. Details of my handloads will appear in the accompanying table. To my pleasant surprise, that old revolver grouped in the 2- to 3-inch range at 25 yards.

44 COLT

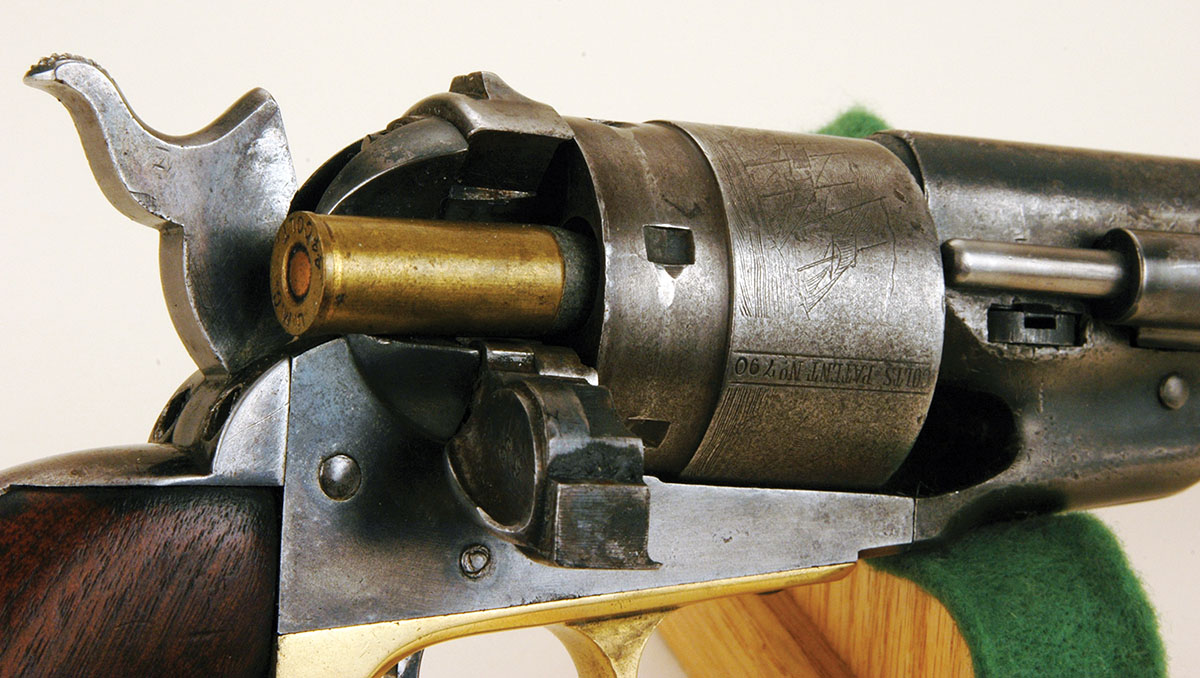

Evidently, the U.S. Army was not 100 percent satisfied with its S&W 44s, for in 1871, they bought 1,200 of Colt’s Richards Conversions chambered for 44 Colt. These conversions used parts originally made for Colt’s Model 1860 44 cap & ball revolvers but with newly-made cylinders. The barrel length was 8 inches. As with the above S&W No. 3, my 44 Colt also lacked martial markings.

Colt’s 44 cartridge case was somewhat larger than S&W’s. Its length was 1.10 inches, with a bullet weight of 210 grains over 28 grains of black powder. Again, bullets were of the heel design but with this round, they were nominally .451 inch. Some 44 Colt cartridges carried lubricant in grooves outside the case and some had 1⁄8-inch beeswax wads beneath bullets with a card wad keeping wax separate from bullets.

Finding brass for a 44 Colt is somewhat easier than with the 44 American because Starline offers it. My handloads used heel-based bullets from the now-defunct Rapine Moulds’ No. 451210. It drops .451-inch bullets weighing 208 grains when cast from 1:20 tin to lead alloy. Rapine Moulds is gone but custom moulds can be ordered from several makers. Groups ran in the 3- to 4-inch range at 25 yards.

45 COLT

The above 44s were rather feeble rounds compared to 45 Colt. By 1873, Colt’s engineers decided a top strap on its revolver frames allowed more powerful rounds. As said earlier, a martially marked Colt SAA has eluded me. However, I’ve been even happier with a U.S. Firearms Custer Battlefield 45. This special run was introduced at the 2004 SHOT Show, which is where I ordered mine and happily got the serial number 1876. In appearance, it almost duplicates the Colt SAA 45 that has long been on display at the Little Bighorn Battlefield museum. It has the additional benefit of being strong enough for smokeless powder factory loads and handloads. A long-lasting fallacy is that 45 Colt military loads contained 40 grains of black powder and 255-grain bullets that gave more than 900 fps from SAA 7½-inch barrels. They were not so loaded. Original loads had 30 grains of black powder with 250-grain bullets with a velocity of perhaps 750 fps. The case length was 1.285 inches.

What can be said about handloading the 45 Colt that hasn’t been said hundreds of times before? Personally, I can say that 30 grains of GOEX FFg black powder under NEI bullet No. 324 weighing 252 grains when cast of 1:20 alloy, provided about 760 fps. Those figures are from 7½-inch barrels. Lyman mould No. 454190 for 250-grain RN/FP is a good substitute for the NEI bullet. Reloading manuals are full of good advice for smokeless loads but for me, 6.2 grains of Trail Boss will suffice with any 250-grain bullets. That’s a mild load and easy on my aged hands

Worthy of mention here is the 1909 45 Colt. The U.S. Army knew that a 45 semiauto pistol was on John M. Browning’s drawing board and that as soon as perfected, it would likely be adopted. Therefore, as a stopgap measure, the U.S. Army selected Colt’s New Service revolver as its Model 1909. The cartridges developed for it were smokeless 45 Colts except the rim diameter was increased from .502 inch for black-powder loads to .534 inch. (Measurements were taken from original cartridges in my collection.) The reason for the wider rim was for sure extraction from New Service star-type extractors. The box of 1909 45 Colt rounds in my collection bears the information that velocity is 725 fps plus/minus 25 fps.

45 S&W SCHOFIELD (45 COLT GOVERNMENT)

This is where the history of the nineteenth-century American military 45s gets a bit convoluted. After the U.S. Army adopted its SAAs, S&W still wanted a share of the pie. A serving U.S. Cavalry officer named John Schofield liked the early S&W Model No. 3 44s but believed he could improve them with ideas for which he quickly gained patents. The remodeled No. 3 revolvers had 7-inch barrels with the most important difference from earlier No. 3s being the top-break latch. In 1875, the army began buying these handguns as a substitute standard for Colt SAAs.

Because the government only wanted 45-caliber revolvers, S&W brought out its first and only .45-caliber cartridge along with Schofield’s remodeled No. 3. It had a case of only 1.10 inches to fit its cylinder lengths. Government loads used 28 grains of black powder under 230-grain RN/FP bullets for a nominal velocity of 725 fps. These loads were also suitable for 45 Colt chambered revolvers.

Naturally, this led to much confusion when longer 45 Colt cartridges were shipped to army posts whose troops were issued S&W No. 3 Schofield revolvers. Soon, the army decreed it would only issue 45 S&W cartridges and did so well into the 1880s. In 2000, S&W introduced a new Schofield to celebrate the original’s 125th birthday.

I’ve owned both new and old Schofields and found them to be fine shooters albeit only black powder was used in the one whose factory letter said it was delivered to the U.S. Government in 1876. The brass is made by Starline and dual-purpose reloading dies for both 45s are offered by RCBS in its Cowboy series. The loads developed over the years for use in both S&Ws and the U.S. Firearms Custer Battlefield 45 Colt are too numerous to detail here. Please consult the accompanying table for details.

38 LONG COLT

Somehow, the U.S. Army’s ordnance folks were persuaded to give up 45-caliber handgun cartridges and so introduced its Model 1892 38 Colt. Although herein, I will refer to it as 38 Long Colt although the revolvers made for it never carried that caliber stamp. All were simply marked 38 Colt. The Model 1892s and later Model 1894 still used oversized bore diameters that were holdovers from the 38 Colt conversions and Model 1877Das. Those had barrel bore diameters of approximately .370 inch, give or take a few thousandths with groove diameters of about .375 inch, again with the give or take of a few thousandths.

The 38 Short Colt had a case length of .88 inches and used outside lubed heel-base bullets of about .380 inch. Eventually, the 38 Long Colt case grew into a 1.03-inch case length with inside lube bullets that required bullet diameter reduction to .358 inch. This change required 38 Long Colt loads to use hollowbase bullets.

Later Model 1903 Colt 38s were given corresponding barrels with groove diameters of .357 inch. Both Models 1894 and 1903 were rated safe with smokeless powders. A Model 1903 with a 6-inch barrel is what I owned and shot previously. However, my chronograph notes have been misplaced, so I’ve taken the liberty of substituting data taken with a Colt Model 1861 38 Conversion with a 7½-inch barrel for black-powder loads and a Colt SAA 38 with a 5½-inch barrel for smokeless-powder handloads. Again, please see the accompanying table for more details. I do want to say that whatever failure the 38 Long Colt was in Philippine Island combat, today it’s a fine round for simple recreational shooting.

45 ACP (45 Auto)

Handloading details need not be discussed as probably a million or more handgun shooters worldwide are reloading 45 ACP. I do want to say that to save wear and tear on my 1918 vintage Model 1911, only a mild load of 4.2 grains of Trail Boss powder under Oregon Trails’ 225-grain cast roundnose bullets is used in it. For more modern Model 1911s, full-power loads for 45 ACP using 230-grain jacketed bullets are an option.

Something I find amusing is that a young officer just entering the U.S. Army in 1871 would have been familiar with all these handguns if he stayed in the service until 1911. Think about that: he could have been issued a S&W 44 American revolver on his first day and then perhaps had a Colt Model 1911 45 semiauto on his last day.

.jpg)