.44 S&W Special (Pet Loads)

Bullets and Powders for Standard Pressure Loads

feature By: Brian Pearce | June, 17

In spite of the frequent criticism of the .44 Special for being somewhat underpowered, it can be amazingly accurate, has been chambered in many top-notch guns and when handloaded offers power and unusual versatility that make it capable of hunting big game, defense or target work. During the past 40+ years, I have shot dozens of big game from pronghorn to black bear and elk with the .44 Special, all with handloaded ammunition. It often produces tight groups and, when developing top-notch handloads, is one of the least finicky cartridges. It ties with two others as my favorite sixgun cartridge.

The .44 Special is based on the black-powder .44 Russian case that earned a superb accuracy reputation in domestic and international target competition. The Special case was lengthened from .97 inch to 1.16 inches and originally loaded with black powder, receiving 3 grains more than the Russian cartridge for a boost in velocity. Early ammunition contained 26 grains of black powder that pushed the 246-grain, lead roundnose bullet 780 fps. Smokeless-powder ammunition soon appeared, and velocities were eventually standardized at 755 fps with the same bullet. For many decades this was the standard load from Winchester and Remington and is still available. Eventually Federal Cartridge offered a 200-grain lead SWC-HP at 900 fps (recently reduced to 870 fps), while Winchester followed suit with a 200-grain Silvertip HP and Remington with a 200-grain LSWC at the same velocity. With a resurgence of interest in the .44 Special, along with outstanding new guns, several smaller ammunition companies are now offering loads with bullet weights that range from 135 to 255 grains at a variety of velocities.

As smokeless powders progressed and improved, by the early 1920s handloaders began developing loads that enhanced the performance of the .44 Special. Most famous was Elmer Keith. During 1927 and 1928, he designed the now-famous Lyman/Ideal .44-caliber bullet 429421 that weighed 250 grains in solid form and 235 grains in hollowpoint form.

In 1953 Keith traveled to the Smith & Wesson and Remington plants to further discuss the matter, at which time he suggested they lengthen the case and make it a .44 Magnum, which became a reality in late 1955. Unfortunately, the .44 Magnum’s greater power pushed the Special from the stage. Nonetheless, many shooters still recognized the virtues of the .44 Special, especially when handloaded, because it offers low extreme spreads, lower recoil and muzzle report, and fired cases clear the chambers with ease. By comparison, revolvers typically chambered for the Special are lighter, handier and better suited for everyday belt carry.

Skeeter Skelton was perhaps most influential for helping to renew interest in the .44 Special, with articles appearing in the late 1960s and 1970s that ultimately helped influence Colt to reintroduce the Single Action Army and New Frontier during the late 1970s (both of which are currently available again), while Smith & Wesson produced its Models 24 and 624 (1950 Target) during the mid-1980s. Many other manufacturers, including USFA, Freedom Arms, Ruger and several foreign companies have offered good-quality sixguns. Skelton’s favorite handload consisted of the 250-grain Keith bullet pushed around 950 fps (4-inch barrel) using 7.5 grains of Unique powder. This load significantly increased the effectiveness of the cartridge while still being easily managed when shooting fast with double- action sixguns. With variables, this load generally produces around 18,000 psi and is a +P load.

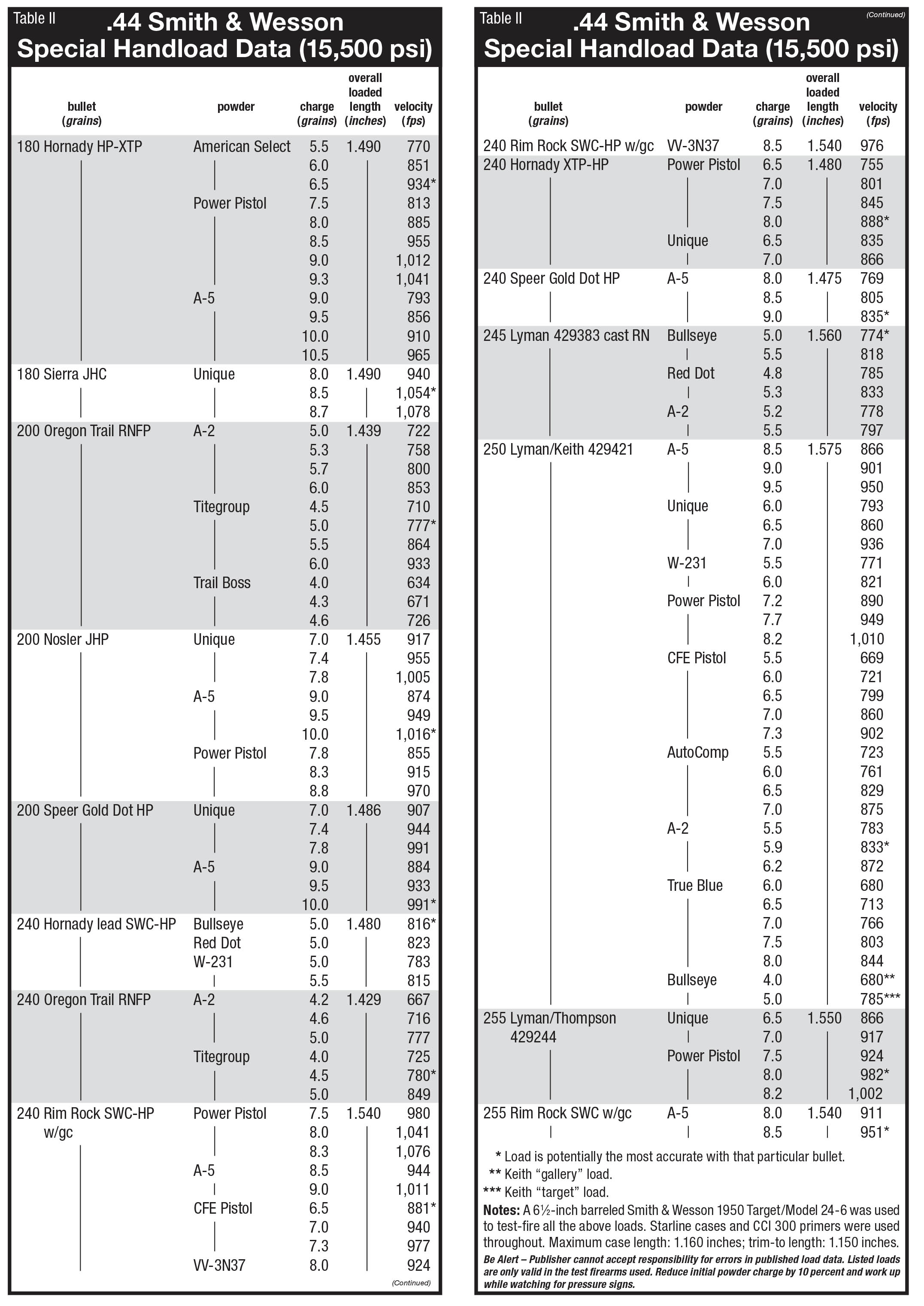

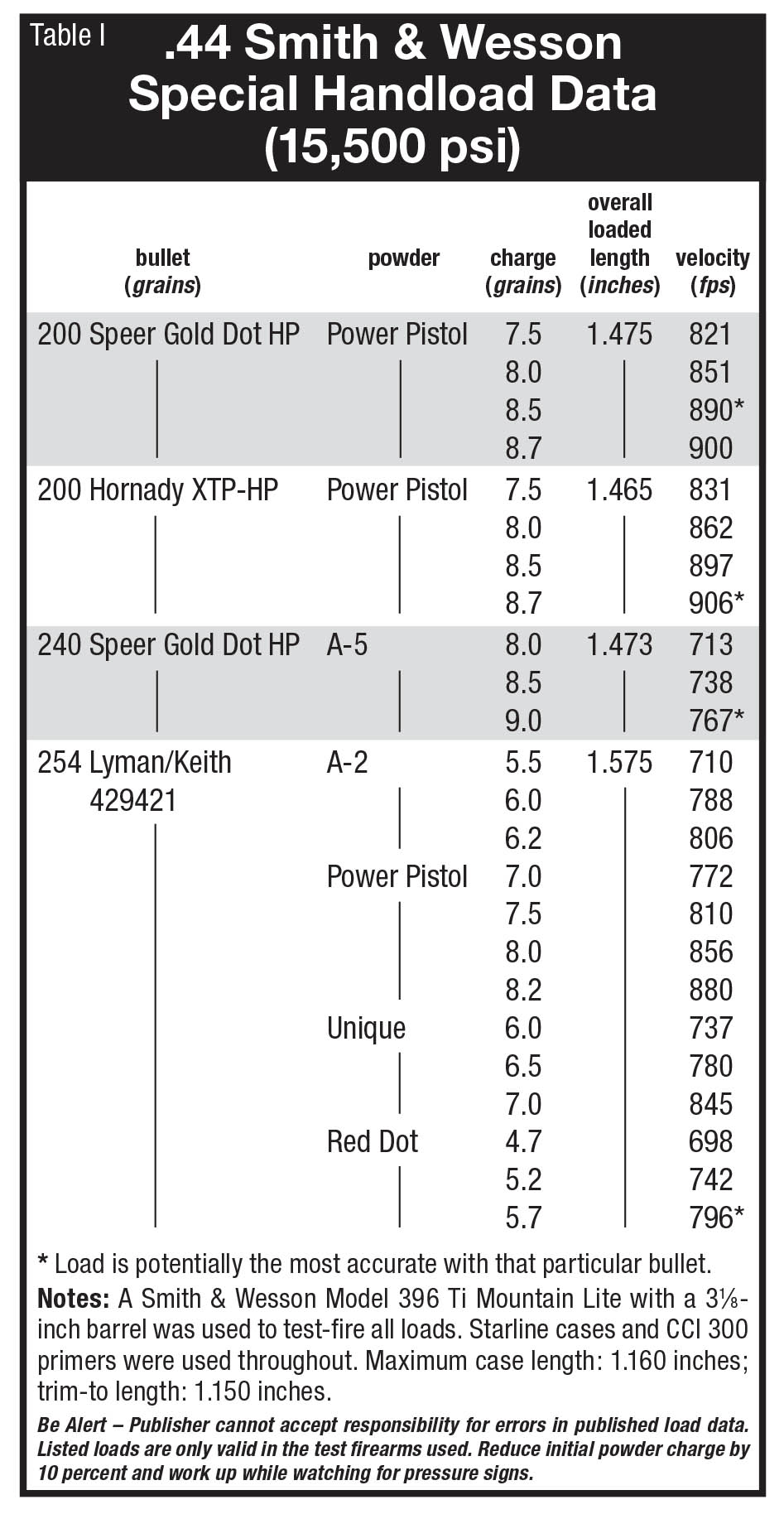

The .44 Special is a joy to handload, but there are some important points to be aware of that will help handloaders assemble top-notch ammunition tailored specifically to their guns. First, not all guns are of equal strength – some will handle significantly greater pressures, while others cannot. Current industry maximum average pressure is established at a rather low 15,500 psi, which is in deference to early sixguns and select U.S.-manufactured and imported guns. This is not a handicap, as many powders are capable of pushing 250-grain bullets 850 to 900 fps (roughly equal to the .45 Colt factory load), while a few select powders can push the same bullets over 1,000 fps while staying within pressure guidelines. Many guns will easily handle loads that generate 22,000 psi, 25,000 psi and even more; those loads will be discussed here in a future “Pet Loads” article. Standard pressure loads are suitable for all guns and are within SAAMI specifications of 15,500 psi.

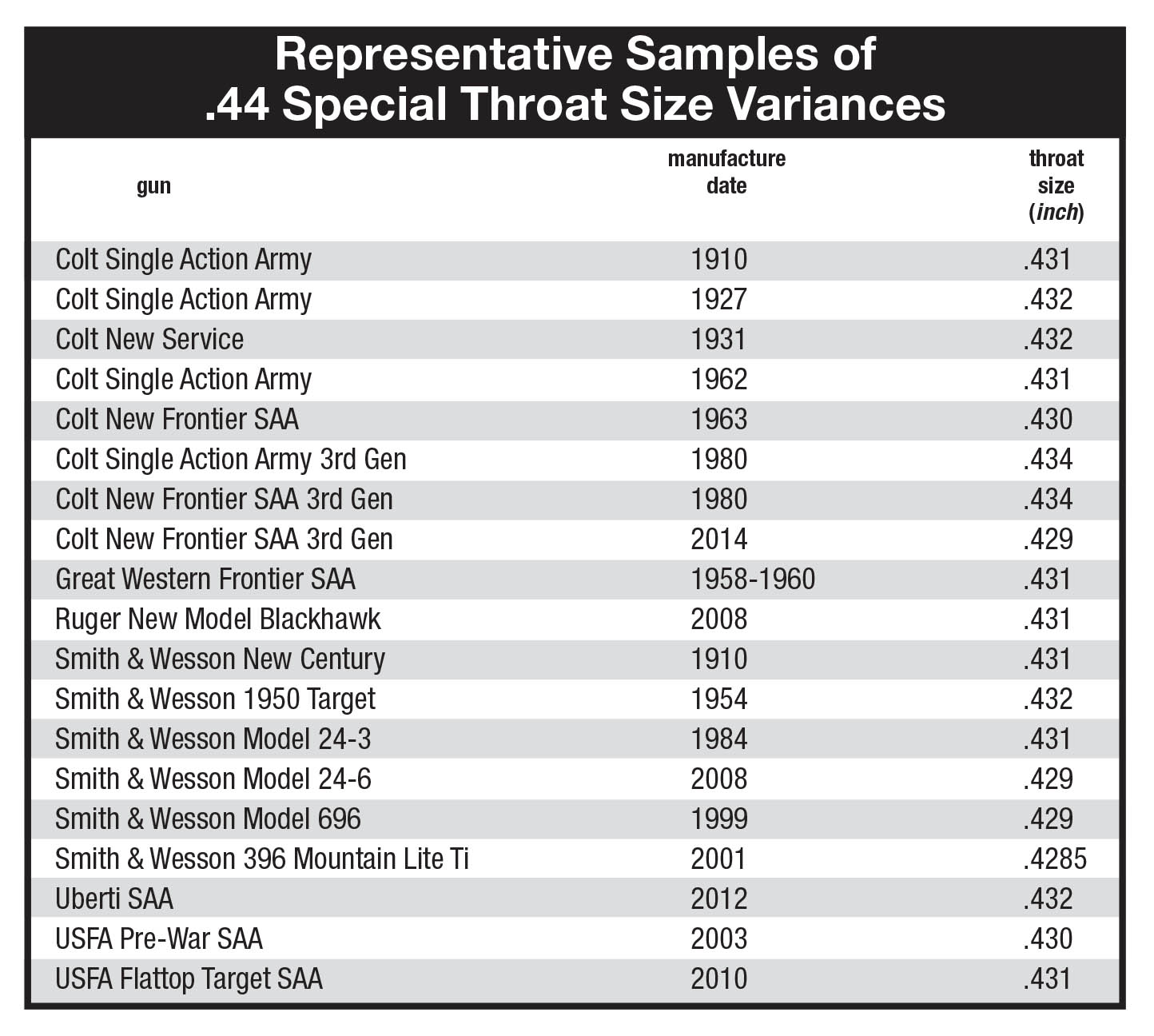

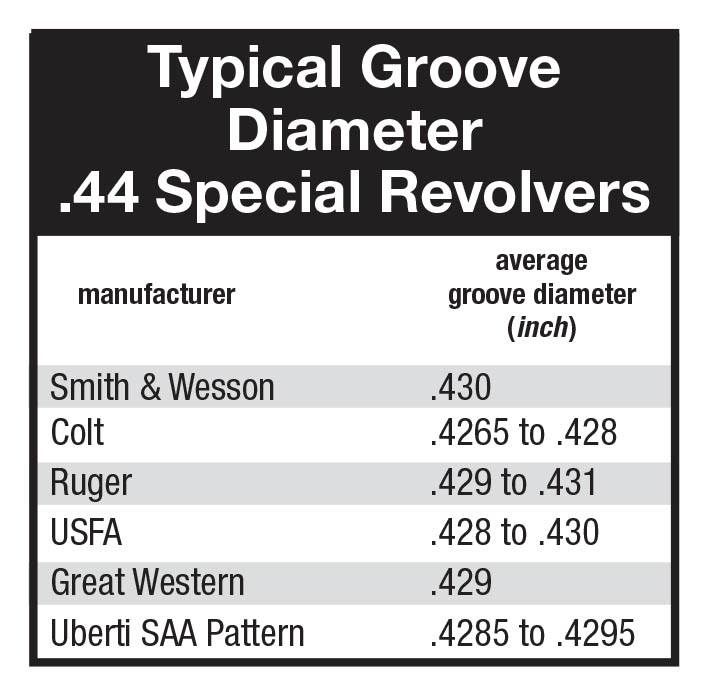

Internal gun dimensions can vary significantly, including barrel groove diameter and throat dimensions. To help illustrate this information, sidebars are included containing sample dimensions from a variety of guns. Study them carefully, as measurements vary even from the same manufacturer. For example, Smith & Wesson N-frame revolvers have historically featured throats that measure .431 to .432 inch, though two L-frame revolvers and a recently manufactured Model 24-6 measured .4285 to .429 inch. A Colt Single Action Army dating back to 1910 measured .431 inch, while a 1963 New Frontier SAA measured .430, a 2014-era New Frontier SAA ran .429 inch, and a 1980 3rd Generation Single Action Army measured .434 inch.

Much has been written about sizing cast bullets to correspond with groove diameter. Tests have shown, however, that using bullets that are close to throat diameter to begin with usually yield best accuracy while increasing pressures very little, if at all. For a general-purpose, one-size-fits-all approach, I usually size cast bullets from .430 to .431 inch.

The .44 Special is an ideal cartridge for cast-bullet loads, with literally dozens and dozens of designs and weights readily available. A few of their advantages include lower cost – especially if you cast your own – substantially reduced barrel wear, greater velocities with less chance of sticking bullets in the bore, straight and deep penetration on game with the added shock associated with a large meplat and good accuracy, especially when loads are tailored to a specific gun.

The 200- and 240-grain Oregon Trail RNFP bullets are good choices for cowboy action competitors. To duplicate vintage factory loads, the 245-grain roundnose from Lyman mould 429383 is a top choice that is fine for small-game hunting. I still favor genuine Keith designs for general use, as they are accurate, perform well on game, are easy to cast, and without a gas check, they are especially economical. The 255-grain Lyman Thompson-designed mould 429244 with a gas check also produces excellent terminal performance and minimizes barrel leading. For those seeking rapid expansion, the Rim Rock 240-grain HP-SWC with a gas check (cast with a BHN of 11 to 12) will expand at around 950 fps, a velocity that can be surpassed with select standard pressure data.

Most modern jacketed bullets must be traveling at least 850 to 900 fps to achieve reliable expansion, a velocity that was easily reached with most 200-grain bullets using standard pressure loads. On the other hand, when pressures are held to 15,500 psi, most powders cannot push various 240-grain jacketed bullets fast enough to expand reliably. For these reasons, 240-grain bullets are best when used in conjunction with load data that exceeds industry maximum pressures. A few loads are offered, however, that utilize the Hornady 240-grain XTP-HP and Speer 240-grain Gold Dot HP.

Excellent results were obtained with fast-burning powders such as Hodgdon Titegroup, Accurate No. 2, Alliant Bullseye and Red Dot. Medium-burn-rate powders, such as Alliant Power Pistol, Unique, Hodgdon CFE Pistol, Winchester AutoComp and Accurate No. 5 are top choices for loads that push standard weight (250-grain) bullets between 900 to 1,000 fps.

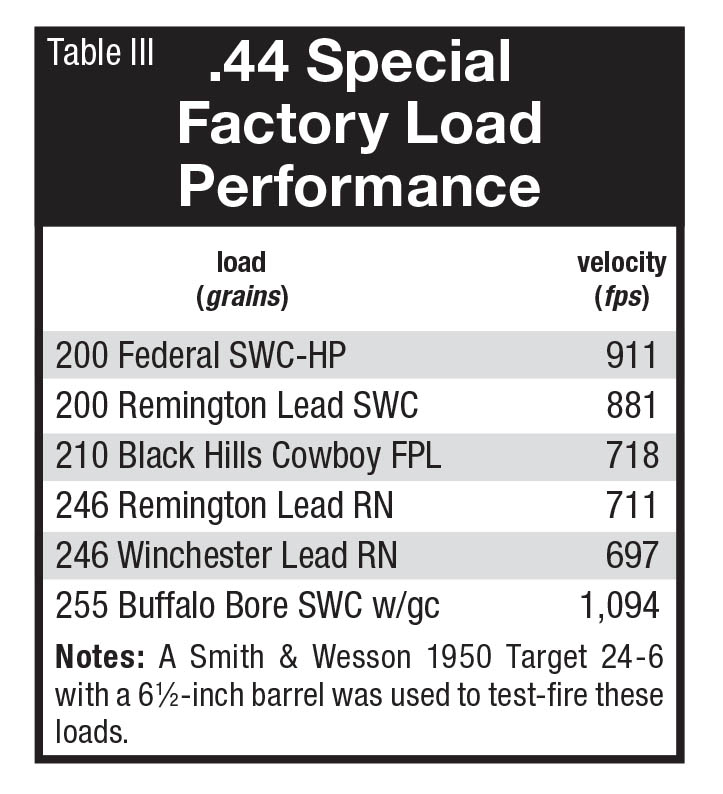

The data in Table II was developed in a 2008 Smith & Wesson Model 1950 Target 24-6 revolver with a 61⁄2-inch barrel. This gun differs from previous models in several areas; most notable is a cylinder length that is the same as the Model 29 .44 Magnum, which results in greater bullet jump or free-bore. The rifling is EDM (Electric Discharge Machining) rather than the traditional Smith & Wesson cut style that was present on all the company’s sixguns manufactured prior to 2000. Also, as previously indicated, the chamber throats measure a comparatively snug .429 inch. All this resulted in changes in muzzle velocity with many loads. What is most interesting is that sometimes velocities were faster than those from an original Model 1950 Target with the same barrel length, but other loads recorded lower speeds.

For general-purpose plinking, target work and even defense, using one of the various 245- to 255- grain cast SWC profile bullets pushed around 850 to 875 fps will prove effective and pleasant to shoot. For a bit more horsepower, including hunting deer-sized game, the load I prefer consists of 8.2 grains of Alliant Power Pistol with the 250-grain Keith bullet, which generally produces around 1,000 fps in most revolvers with barrels of 43⁄4 to 61⁄2 inches (or 950 to 975 fps with 4-inch barrels). It is within industry pressure guidelines at 15,500 psi, while offering moderate recoil and good accuracy.