Go-To Handloads

Bullet and powder combinatioins that work.

feature By: Mike Venturino | June, 17

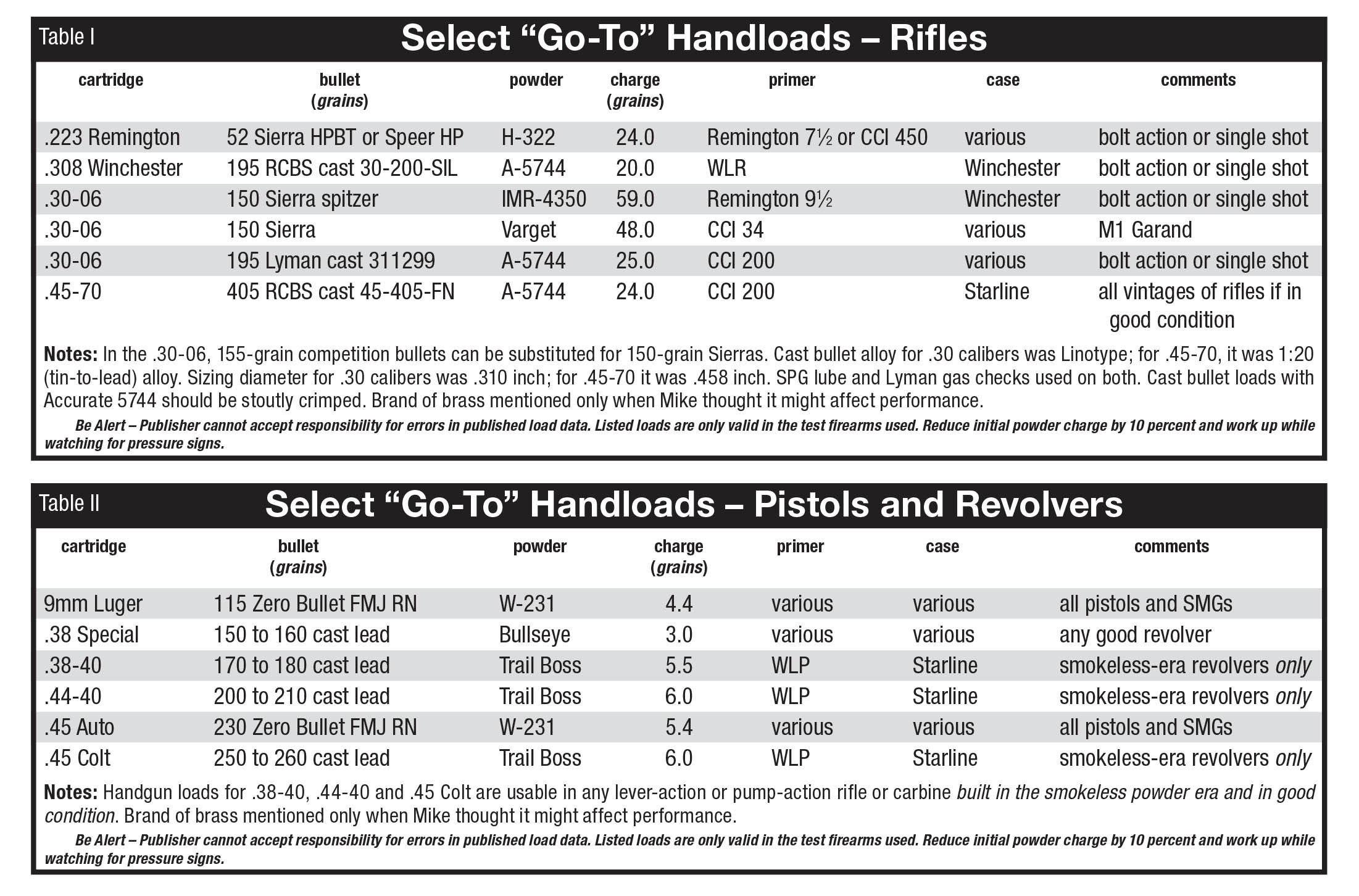

Like many readers, my first handloading for rifles began with .30-06 and Model 70 Winchesters. After a considerable amount of shooting, a charge of 59.0 grains of IMR-4350 with Sierra 150-grain spitzers became a go-to load. In current reloading manuals, that charge is over maximum, under maximum or at maximum – take your pick – but in the Lyman manuals I had back in the 1960s, it was a grain or two below maximum. Besides Model 70 and Model 54 Winchesters, that load has been used in Remington Model 721s and 700s, Savage 110s, Ruger M77s and likely others I’ve forgotten.

It is an accepted fact that M1 Garands should not be fed handloads with slower propellants, such as IMR-4350, for fear of

Like many .44 Remington Magnum shooters of the 1960s and 1970s, my starting point was Elmer Keith’s recommended 22.0 grains of 2400 with 250-grain semiwadcutters cast in Lyman mould 429421. In machine-rest testing, 21.0 grains of 2400 proved more accurate, as did Lyman’s gas-checked 255-grain bullets from mould 429244. That combination was the go-to formula for all .44 Magnums fired thereafter.

Powders are usually the heart of go-to loads. For instance, back in the 1970s and early 1980s, I went through a varmint rifle craze. After trying most every varmint cartridge from .222 Remington to .25-06, favorites became the .222 Remington, .222 Remington Magnum and .223 Remington. Go-to loads for the latter two included 24 grains of Hodgdon’s H-322 powder and either Sierra 52-grain hollowpoint boat-tails (HPBTs) or Speer 52-grain hollowpoints (HPs). The .222 Remington fell by the wayside, but it provided an educational experience.

With the derivative cartridges based on the .30-06 – namely .25-06 Remington, .270 Winchester, .280 Remington and one .338-06 owned many years back – IMR-4350 was always my go-to propellant. The same is true for the .22-250 Remington, .244/6mm Remington, .257 Roberts and 7mm Mauser. In fact, H-322 and IMR-4350 are easily my primary rifle propellants.

At this point I should stress that “go-to” does not translate into “always used.” In my military bolt-action .30-06s, the charge is reduced to 55 grains of IMR-4350 – not to ease wear on the rifles but because the lesser charge gives velocities duplicating M2 Ball military ammunition.

Some powders of which I’m not overly fond are central to one of my go-to handloads. A good example is H-110. It has never worked well for me in magnum handgun cartridges but shines in the .30 Carbine. On hand are three M1s and one M2 (select-fire), and a charge of 14.5 grains under any 110-grain FMJ or JSP bullet functions perfectly with adequate groups.

Now to some of the “Old West” cartridges of which I’m so fond. Three favorites for handguns are the .38 WCF, .44 WCF and .45 Colt. In their original configurations, their respective black powder factory loads, according to an 1899 Winchester catalog, were 38, 40 and 38 grains with 180-, 200- and 255-grain bullets in the same order. For many years my favorite handloads for those cartridges used 6.8 grains of W-231 or HP-38 with bullets of the same weights listed above, give or take 5.0 grains or so. Years ago bullets were cast of wheelweight alloy blended with 50/50 solder (half tin, half lead) to give a BHN of about 12 to 15. Today the same 1:20 (tin-to-lead) alloy as is used in my BPCR Silhouette handloads actually serves with less leading than harder alloys.

In the early twenty-first century, Hodgdon introduced a fast-burning propellant that took up far more volume in black powder cartridge cases. Whereas several charges of 6.8 grains of W-231/HP-38 could inadvertently fit in those huge cases, a double charge of this new powder comes close to or actually overflows from the case. Hodgdon named it IMR Trail Boss, and it quickly became my go-to powder for most handgun cartridges originally introduced for black powder. (A notable exception is the .38 Special, in which Bullseye is mainly used.) In the .38 WCF, .44 WCF and .45 Colt, my Trail Boss charges are 5.5, 6.0 and 6.0 grains, respectively. When I have time to cast bullets for those three cartridges, RCBS 40-180-CM, RCBS 44-200-FN and NEI 324 bullets are preferred. All are roundnose-flatpoint (RN/FP) versions sized .401, .428 and .454 inch, respectively. When time is short, Oregon Trail 180-, 200- and 250-grain RN/FPs are substituted.

Once early on, the 9mm MP40 revealed it was gummed with greasy, unburned powder by firing continuously after the trigger was released but until its magazine was empty. The culprits were a combination of mild pressures and cast bullet lubes. Its barrel also leaded severely when using lead-alloy bullets. For these reasons, my go-to 9mm and .45 Auto handloads use full-metal-jacketed (FMJ) bullets – 115- and 230-grain designs from Zero Bullet Company. Accordingly, they are .355 inch and .451 inch in diameter. Powder charges, respectively, are 4.4 and 5.4 grains of W-231 or HP-38. A Dillon Square Deal-B progressive press is set up for each of those cartridges, and settings are never changed but are checked often. Those FMJ handloads are also fine for my plethora of modern and vintage 9mm and .45 Auto handguns.

For every rifle owned, I’ve tried to also have at least one bullet mould for it, although I don’t have a mould for the 6.5x52mm Carcano or 7.92x33mm Kurz. I’m convinced, however, that the key to getting good accuracy across the board with just about any cast bullet rifle load is Accurate 5744 powder. Never have I experienced such accurate cast bullet handloads in rounds from .222 Remington to the .45-90 Sharps and Winchester as with this powder.

As an experiment a few years back, 20 grains of A-5744 was poured in .308 Winchester cases and RCBS 308-200-SIL and Lyman

The same Lyman bullet over 25 grains of A-5744 in several of my military .30-06 bolt actions gives 11⁄2-MOA groups at 100 yards. Putting 27 grains of it under a 190-grain Redding/SAECO 081 bullet sized .325 inch and gas checked cuts the same size groups from several 8x57mm military rifles. Results have been the same for at least a half-dozen other vintage military cartridges.

The same is true in big bores. In .45-70s with RCBS bullet 45-405-FN, sized .458 inch and using Hornady gas checks, 24 grains gives low enough pressures for good condition 1800’s vintage rifles, such as “trapdoor” Springfields, original Sharps Model 1874s, Remington No. 1 rolling blocks and Winchester 1886 and Marlin 1881 rifles. According to Lyman’s current Cast Bullet Handbook 4th Edition, .45-70 loads with A-5744 can be upped for higher velocities in “stronger” .45-70 rifles, but a 405-grain bullet at 1,200 to 1,300 fps has plenty enough recoil for me.

Handloaders need not concern themselves with any special antics when using A-5744, such as case fillers or wads to hold powder back near the primer. In fact, using fillers ensures the rifles’ chambers will be ringed sooner than later. The only step I take with any cartridge with cast bullets and A-5744 propellant is to apply a solid crimp on the bullet to help ensure clean burning of the powder.

Developing match-quality hand-loads for BPCR Silhouette shooting is a detailed endeavor about which I’ve written previous articles and even books. However, one go-to tip I can give in the space here is about bullets and .45-70s. When a new .45-70 single shot gets into my mitts, its first test rounds carry Lyman’s 457125 bullets cast of 1:20 alloy, sized .458 inch and lubed with SPG. That bullet, seated over whatever amount of black powder chosen, at the seating depth allowed by the rifle’s chamber and sparked by CCI BR2 primers will likely indicate if the rifle will be competitive. Or in plain language: Is it worth putting more effort into developing match loads?

There are many more go-to hand-loads, mostly for cartridges for esoteric rounds like the 8mm Japanese Nambu or 7.5x54mm French. Those listed in the tables are for more popular cartridges. By no means have I settled on go-to loads for each and every cartridge for which guns are currently in my vault. Hopefully in the near future there will be more to share.