7mm Remington Magnum

New Bullets and Powders

feature By: John Barsness | August, 20

Two thoughts come immediately to mind: First, back then many hunters still believed roundnosed bullets worked better when hunting in heavier cover, due to less deflection when “bucking brush.” In fact, some of the era’s other new belted magnums came saddled with roundnose bullets, including the .257 Weatherby’s 117-grain factory load.

Also, Remington might have had a bunch of 7mm roundnose 175s on hand, due to shrinking demand for the 7x57 Mauser, the only other cartridge Remington ever loaded with that bullet. Before World War II, the 7x57 had been relatively popular in the U.S. – Winchester even chambered it in the pre-’64 Model 70 – but faded after the war. The factory ammunition lists in the 1963 Gun Digest annual (where Ken Waters reviewed Remington’s new 7mm cartridge) did not include any Remington 7x57 ammunition.

Some reviewers mentioned this ballistic anomaly, but Remington didn’t fix the problem for a few years, perhaps after finally loading the last of its roundnose 175s. The factory ammunition tables in the 1966 Gun Digest listed a “PCL” (Pointed Core-Lokt) 175-grain load, rather than the 175-grain “SPCL” (Soft Point Core-Lokt roundnose) in earlier editions. Listed velocity also rose from 3,020 fps to 3,070 fps, due to DuPont developing a new, slow burning powder named IMR-7828, apparently at least partly for the 7mm Remington Magnum, which for some unknown reason Remington did not sell to handloaders until a quarter-century later.

The 7mm Remington Magnum solved both problems because it appeared in the new 700 rifle priced to compete with the Model 70. As a result, the cartridge soon became a standard worldwide chambering, filling the slot between the .270 Winchester and various .30 calibers.

The sales surge resembled the combined popularity of the most successful pair of twenty-first-century centerfire rifle cartridges, 2002’s .300 Winchester Short Magnum and 2007’s 6.5 Creedmoor, but the 7mm Remington Magnum surge lasted longer. The .300 WSM peaked within a few years, and friends in the retail gun business even say the Creedmoor craze has started to slow. Fellow gun writer John Haviland worked for a pulp mill in western Montana from 1979 to 1987 and has joked that “every worker was issued a hard hat and a 7mm Remington Magnum.” Lunch break conversations often consisted of guys bragging on their “Big Seven,” sometimes as obnoxiously as some 6.5 Creedmoor fans (and detractors) today.

Remington pointed out that the 150-grain load beat the .270 Winchester by a considerable margin, and the 175-grain load beat the 180-grain .30-06. This was true, even though the 7mm ammunition was tested in 26-inch barrels while most factory rifles (including Remington 700s) had 24-inch barrels. Speer chronographed a bunch of factory loads in a Remington 700 for its Number 6 Speer Manual for Reloading Ammunition published in 1964: the 150-grain load got 3,135 fps and the 175 recorded 2,990.

However, during John’s pulp-mill period, published velocities of Remington factory ammunition dropped considerably, particularly for the 175-grain load. The 150-grain load lost 150 fps, dropping to 3,110 fps, and the 175 lost 210 fps, down to 2,870 – but these still beat the .270 and .30-06.

The drops apparently occurred due to changes in pressure measurement by the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturer’s Institute (SAAMI), consisting of companies (not all American) to make sure all factory ammunition is safe in all factory rifles. The standard bolt-action test barrel shrank from 26 to 24 inches, and more sensitive electronic pressure measurement started to replace the copper-crusher system.

Since the major handloading component companies publishing pressure-tested loading data also belonged to SAAMI, listed velocities in manuals also dropped. Even in the twenty-first-century, when new (and improved!) rifle powders seemingly crop up every month, my search of up-to-date loading data did not reveal any 7mm Remington Magnum handloads significantly beating the piezo-electronic velocities of Remington’s 150- and 175-grain Core-Lokt factory ammunition.

When writing handloading articles, my standard methodology is to use powders with the highest listed velocities for specific bullet weights, along with a few others listed by loading manual publishers as the most accurate during their testing. Barnes and Nosler, for instance, have long noted the most accurate powder for each bullet weight. Most modern handloaders (unlike those addicted to ancient cartridges, whether smokeless or black powder) tend to demand a minimum muzzle velocity, especially for “magnums.” Otherwise their magnum rifle cannot really be regarded as a magnum, whether by their friends or otherwise.

My definition of “new” includes powders and bullets introduced from 2000 on. This may seem arbitrary, but the cutoff had to be made somewhere. The test “platform” was my own Mauser M18, partly because of being typical of many twenty-first-century factory rifles, including a finely adjustable trigger, smooth hammer-forged bore and an excellent (if somewhat unconventional) stock-bedding system. However, its detachable magazine also holds five rounds, not the three rounds traditional in magnum bolt actions. This may never make a difference in the field, but over the decades I have found a hunting rifle’s magazine tends to be handier for carrying “extra” rounds than anyplace else.

The tests used Hornady brass for two reasons: The consistency is very good and Hornady cases can be purchased relatively inexpensively in several local stores. I started by buying one 50-case box, and after weighing and measuring all 50, found they were essentially match grade, with neck diameters varying no more than .001 inch. I then went back and bought another box with the same lot number. I loaded the test ammunition with Redding dies.

As can be seen in the table, both the M18 and the new powders and bullets performed very well. Some combinations obviously did not agree with the rifle, for whatever unknown reason, but some did. One mild anomaly involved Alliant Reloder 26, considered by many handloaders the new “Wonder Powder,” capable of substantially more velocity in some cartridge/bullet combinations than any other, such as 150-grain bullets in the .270 Winchester, producing muzzle velocities over 3,000 fps even in 22-inch barrels.

In the 7mm Remington testing RL-26 worked very well with bullets up to about 140 grains, but accuracy fell off with heavier bullets, perhaps because the charges did not fill as much of the case, resulting in slightly less consistent powder ignition. The listed 67-grain charge with the 160-grain Nosler AccuBond has already proven popular among 7mm Remington Magnum handloaders. While it certainly grouped well enough for big game at typical ranges, two other powders shot more accurately, especially IMR-8133, which filled noticeably more of the case.

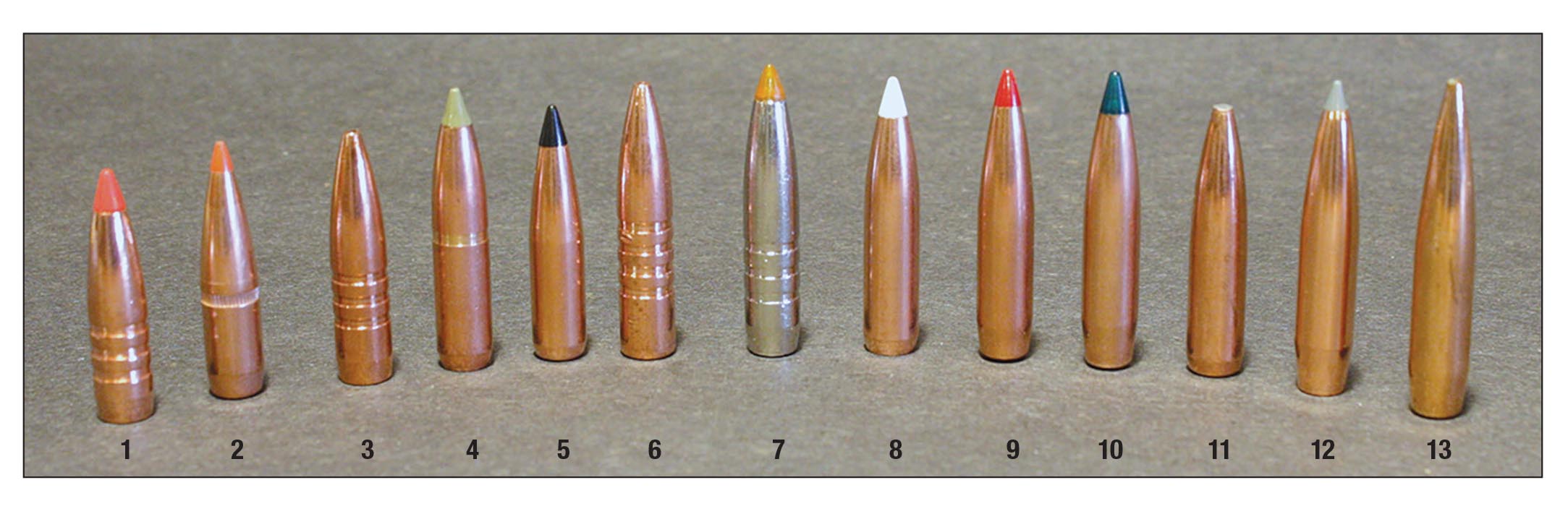

I tested more bullets in the 160- to 165-grain range than any other, partly because just about every bullet company makes them, and partly because many 7mm magnum fans believe bullets around 160 grains result in the best all-around ballistics for big-game hunting with around 3,000 fps at the muzzle. (My late Idaho friend Stu Carty used to say: “There’s just something about all those zeros!”) Other hunters might choose the initially super-flat trajectory of the 120-grain Barnes TTSX at over 3,400 fps, or the super-high .387 G7 BC of the Berger 195-grain Extreme Outer Limits Hunter for less wind drift and more retained energy at very long range.

Velocities tended to be slightly lower than the published data, not unusual when factory barrels are compared to pressure barrels, which tend toward minimum chamber and bore dimensions. None of the loads showed the slightest indication of excessive pressures, whether in velocities or traditional signs such as bolt lift.

Alliant Reloder 26, IMR-8133 and Vihtavuori N560 all contain decoppering agents, and I alternated their loads with the other powders through the tests, looking through the barrel with my Gradient Lens Hawkeye bore scope after each range session to see how much copper fouling built up. Only a minor trace appeared during the first session, and never increased during the tests, so I did not bother cleaning the bore except by swabbing with a few patches soaked in rubbing alcohol to knock back the slight powder fouling before inserting the Hawkeye. The rifle kept shooting well.

These days, some younger shooters tend to regard the 7mm Remington Magnum as antique, partly because of the belted brass. One of my younger friends, in fact, describes it as a “geezer cartridge.” I became curious enough to initiate a survey on the internet chat room 24hourcampfire.com, asking fans of the 7mm Remington Magnum to respond with comments and their age. This eventually devolved, of course, into a heated debate about the pros and cons of the cartridge, but before then I got enough data to firmly indicate the 7mm Remington Magnum remains a popular choice among all big-game hunters, not just those of a certain age.

The average age turned out to be 56.8 years, a year or so younger than the cartridge itself, obviously not all “victims” carried along by its initial popularity. The respondent’s ages ranged from 34 to 77, with over half in their 40s and 50s. This happens to correspond with a 2019 study of the ages of Americans who bought hunting licenses, where about half ranged from 45 to 64 years old. (My friend who called the 7mm Remington Magnum a geezer round is 58 – but like a lot of hunters – apparently feels younger.)

I bought my first 7mm Remington Magnum during my 30s, a used Whitworth Mark X Mauser with a nice walnut stock, priced too low to resist, and have since owned four others, one custom built on the 1909 Argentine military 98 action, a Remington 700, Browning A-Bolt and a Mauser M18. All shot very well, as have various other 7mm Remington Magnums I have handloaded for, whether factory test rifles and or belonging to friends, one a post-1963 Model 70 Winchester owned by my late outfitter friend Richard Jackson.

I have seen the 7mm Remington Magnum at work on big game from Alaska to Africa, especially on numerous deer-sized and elk-sized animals. When the shooter shot well, the rifle did the job well – and I have only encountered one shooter who couldn’t handle the 7mm Remington Magnum’s recoil. This happened in the 1980s, when I guided hunters for a central Montana outfitter, mostly after pronghorns and mule deer. This client had purchased the rifle specifically for an antelope hunt, rather than bring the .243 Winchester he had used for decades on whitetails back East, where he lived. He did not shoot his new rifle much before the hunt, and during the scope-check session obviously flinched pretty hard, but some coaching solved the problem and he got a big buck with one shot.

In contrast, I have encountered many hunters who could not shoot various .300 magnums very well – yet insist on using one in preference to a 7mm magnum. As a result, I eventually concluded that many hunters rate the “killing power” of cartridges by how hard they recoil, not by how they actually kill. Bullets and placement have always been the two biggest factors in killing power, and since the 7mm Remington Magnum recoils more like a .30-06 than a .300 magnum, most hunters shoot them well, whether on pronghorns and impala, or elk and gemsbok. No wonder Remington’s Big Seven remains such a popular choice among hunters of all ages, all around the world.

.jpg)