Cartridge Board

.416 Weatherby Magnum

column By: Gil Sengel | August, 20

Thus, accumulating rifles for several applications can almost be seen as a duty. A bit puzzling, however, is the interest in real, honest-to-goodness, dangerous-game rifles. I am not talking about collectors here, but ordinary shooters who own, or are planning on buying, such rifles even though they know they will never hunt such animals.

What, after all, is dangerous game? Basically, these are animals with the size, quickness and especially attitude that causes them to not tolerate smelly little humans very well, particularly those who sneak around and shoot at them! Four of the African Big Five possess these traits in spades; the leopard makes up in speed and attitude what it lacks in size. Alaskan brown bears and polar bears qualify, as do the big wild cattle located in tropical areas of the world.

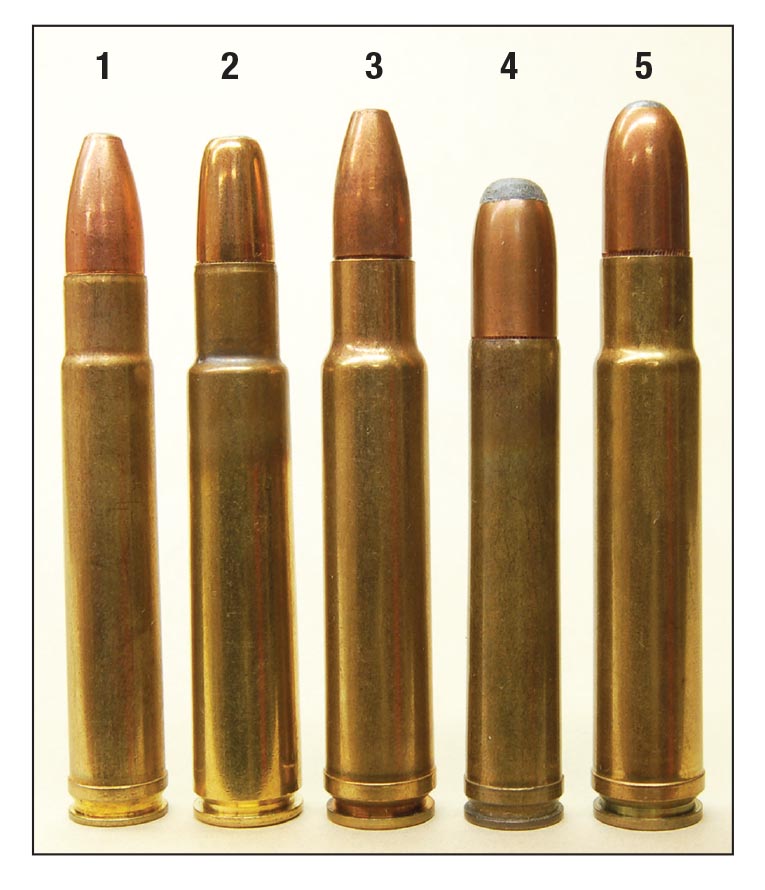

Cartridges suitable for such work are above .40 caliber, and when fired the rifle kicks like two Missouri mules. Most such cartridges are of British origin and thus tend to be pricey, even in well-used rifles.

The Europeans made a few such rifles and cartridges. Most notable is the 12.7x70mm Schuler (aka .500 Jeffery). European rifles are also quite expensive.

Wildcat cartridges, however, are numerous. Availability of new empty cases for .416 Rigby, .505 Gibbs and .577 Nitro Express 3-inch means anything is possible. Drawbacks are expensive custom rifles, costly custom loading dies and lack of pressure tested load data.

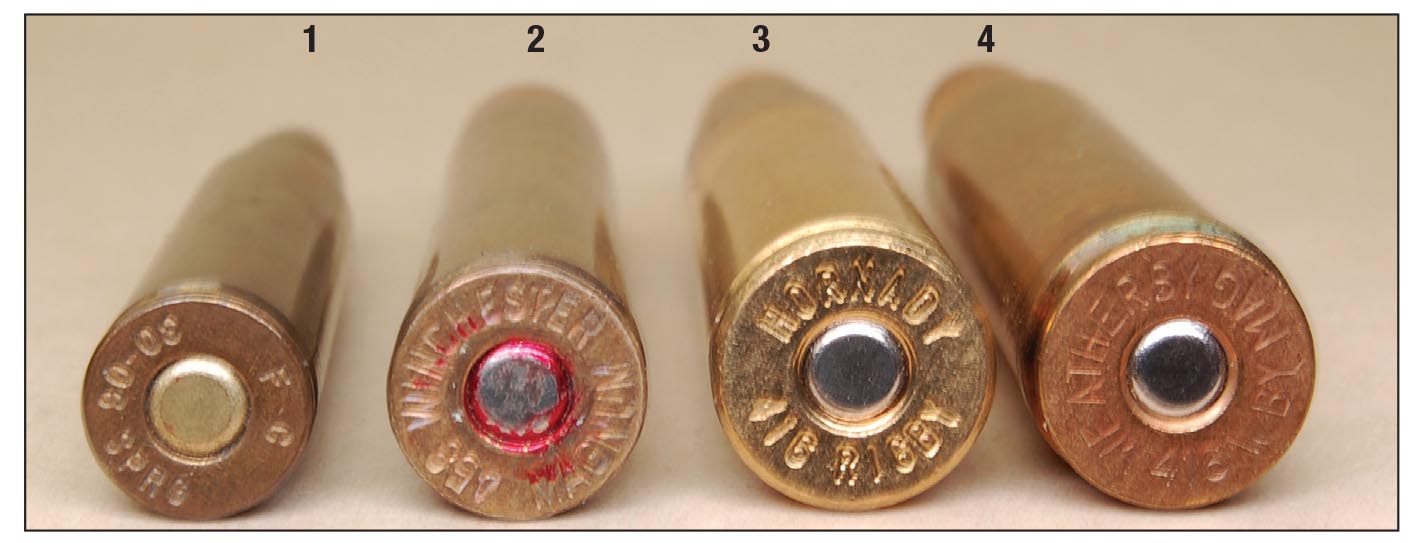

For most people, an American factory offering is the only way to own and shoot a real dangerous-game cartridge. Of these, the .458 Winchester Magnum is by far the most popular. So popular, in fact, that it has been opined that the number of them in gun safes across the country is greater than the total number of elephants killed by sport hunters since the advent of the metallic cartridge!

There are, however, a couple other dangerous-game cartridges that have none of the previously mentioned drawbacks. One is the .416 Weatherby Magnum. It is a big cartridge available in new, properly-sized bolt rifles that are not as costly as British bolt guns. Being a factory round, it also has none of the rifle building or ammunition-making problems of wildcats.

Riflefolk who hear the name Weatherby today usually think of a rifle because of the company’s many variations of rifles chambered for standard cartridges. Older shooters, however, think “cartridges” – Weatherby’s line of original rounds featuring big cases, lots of powder and screaming velocities. The .416 Weatherby Magnum is cut from the same cloth.

Everyone knows or can easily find the history of Weatherby as a company, so I won’t go into that here. Suffice to say that founder Roy Weatherby’s original interest was higher velocity, flat-shooting cartridges for deer, sheep, elk and the like.

When the cartridge line was expanded to fire bullets above .33 caliber, it was found that the standard full-length belted case didn’t hold enough powder. The solution was absolutely brilliant.

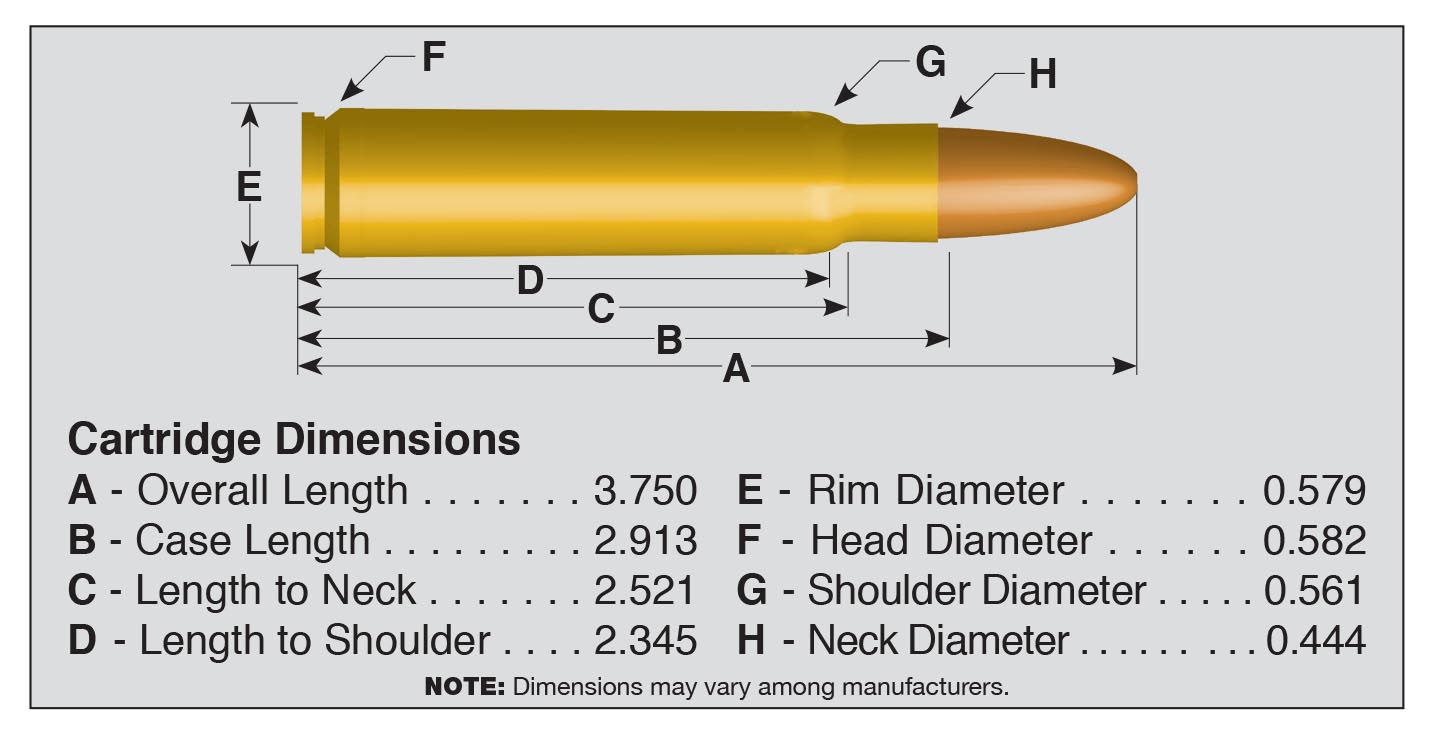

Weatherby did not reinvent the wheel with some kind of new case having supposed magical properties. Instead, he used a case well proven in properly-sized bolt actions. It was the much larger .416 Rigby, which had been around since 1911, and added a so-called magnum belt above the extractor groove. Powder capacity increased about 35 percent over standard belted cases.

The first cartridge built on the new case contained .375-inch diameter bullets and was called the .378 Weatherby Magnum. Adding over 300 fps to the same bullets used by the .375 H&H Magnum caused bullet failure at close range on dangerous game. While this was the late 1950s, much the same is true today. Premium bullets must be carefully selected for the cartridge.

Roy Weatherby fixed this problem in 1958 by necking the .378 Weatherby case up to .45 caliber. Measured muzzle velocities of 500-grain bullets showed an increase of 15 to 20 percent over the .458 Winchester Magnum. Perhaps a bit too much of a good thing, but use of a proper premium bullet tames the velocity on close-up shots.

Given the history of interest in dangerous-game cartridges and Weatherby’s desire to produce them, it is puzzling why the .416 Weatherby Magnum was the last instead of the first round built on the belted Rigby case. Research indicated Roy Weatherby’s son Ed was responsible for its creation and introduction in 1989, one year after the .416 Remington Magnum. The Remington cartridge pushed a 400-grain bullet 2,400 fps, or 100 fps faster than original .416 Rigby loads. Energy was 5,100 foot-pounds at the muzzle. Weatherby’s .416 cartridge generated 2,700 fps and 6,500 foot-pounds with the same bullet, and, yes, it kicks like two Missouri mules – maybe three!

It has been known for 100 years that impact velocity of large cup-and-core bullets could not exceed about 2,200 fps without deformation, which leads to lack of penetration. This is not acceptable for dangerous game. The .416 Weatherby’s blistering muzzle velocity makes modern trick bullets mandatory, either those designed for some expansion or brass-alloy solids.

The .416 Weatherby Magnum burns lots of powder, makes lots of noise and offers very flat trajectory. With its various 400-grain bullets at 2,700 fps muzzle velocity, it produces 45 percent more energy than the .458 Winchester Magnum and allows a dead-on hold out to at least 250 yards. The 350-grain Barnes TSX factory load at 2,880 fps stretches this to near 300 yards, where it delivers more than 4,300 foot-pounds of energy. Both distances are much farther than should ever be considered for any dangerous game!

Nevertheless, wood-stocked Mark V rifles compare favorably to new full-custom guns. They hold their value well (wood-stocked rifles) and are available without a two to three year wait. Best of all, if the recoil seems a bit brisk or power excessive, remember the .416 Weatherby Magnum is just a .416 Rigby with a belt. There is much tested Rigby loading data that will safely drop the Weatherby’s velocity and make it more manageable.

For that group of riflefolk who want a real fire-breathing, dangerous-game rifle, and one that can be throttled back for other than African dangerous game, the .416 Weatherby Magnum is a superb candidate.

.jpg)