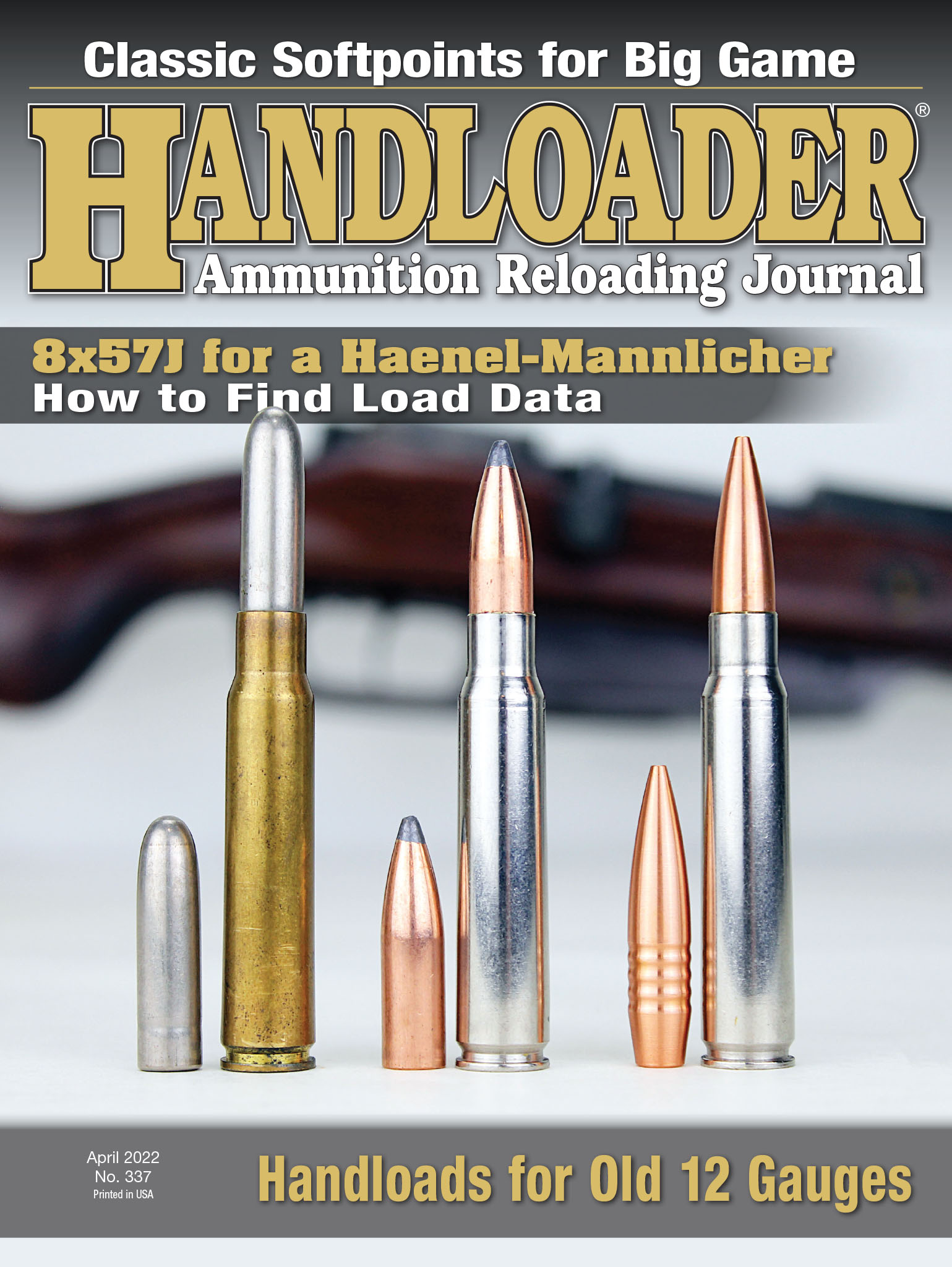

8X57J for a Haenel-Mannlicher

How to Find Load Data

feature By: Art Merrill | April, 22

Germany’s Rifle Testing Commission in Spandau approved the Commission Rifle of 1888, borrowing trigger, safety and firing elements from Peter Paul Mauser’s Model 1871, a box-type magazine from Ferdinand von Mannlicher and a bolt with dual front locking lugs from the French Model 1886. Though this military 1888 Mauser-Mannlicher action was quickly superseded, German arms makers in Suhl, Germany, produced and built commercial guns on it into the 1930s.

Among the better remembered are what we now call Haenel-Mannlicher-style rifles from firms like C.G. Haenel and V.C. Schilling; higher-end examples featured figured-wood stocks with cut checkering, butterknife bolt handles, double-set triggers and engraving. But there were many other Haenel-Mannlichers of more utilitarian bent as well, though these, too, sported aesthetic features like engraving and checkered bolt knobs. A latter example is presented here.

Most obvious to bolt gunners is the Mauser-Mannlicher action’s split receiver bridge, which allows passage of the bolt handle and cocking piece through the receiver. Not considered a detriment at the time, the split, however, is a weak point in the design compared to the Model 98 and other modern bolt actions. Cartridges of the day were loaded below the action’s accepted maximum working pressure of about 45,000 psi, and shooters of these old actions today should adhere to that same parameter.

One of the action’s undesirable features is the need for an enbloc clip that holds five rounds. The clip is designed to stay within the magazine until the last round is chambered, upon which, it falls out of an opening in the bottom of the magazine. The opening is a large entryway to admit dirt, debris, swarming bees and whatever else might be attracted to it. Military M1888 actions had a removable stamped spring steel plate to cover the opening, but these are frequently missing from surviving rifles. If this commercial Haenel-Mannlicher rifle originally shipped with one, it is gone, too.

This rifle’s maker may well remain forever unknown; the rifle bears not a single mark – neither maker, assembly, acceptance proof, caliber designation or importer marks. Slugging the 20-inch octagonal barrel revealed a bore diameter of .306 inch and groove diameter of .317 inch; twist rate is 1:9.5.

The rifle’s cartridge is a handloading challenge. Originally known as the 7.9mm Model 88 Cartridge – Germany introduced it concurrently with the Model 1888 Commission rifle – outside the military, it carried the moniker of 7.9x57mm, and when commercial enterprises got a hold of it for hunting, it became the 8x57 Mauser or 8mm Mauser. An excellent hunting cartridge still bears that name today, but it is a different beastie than the 7.9mm Model 88 Cartridge.

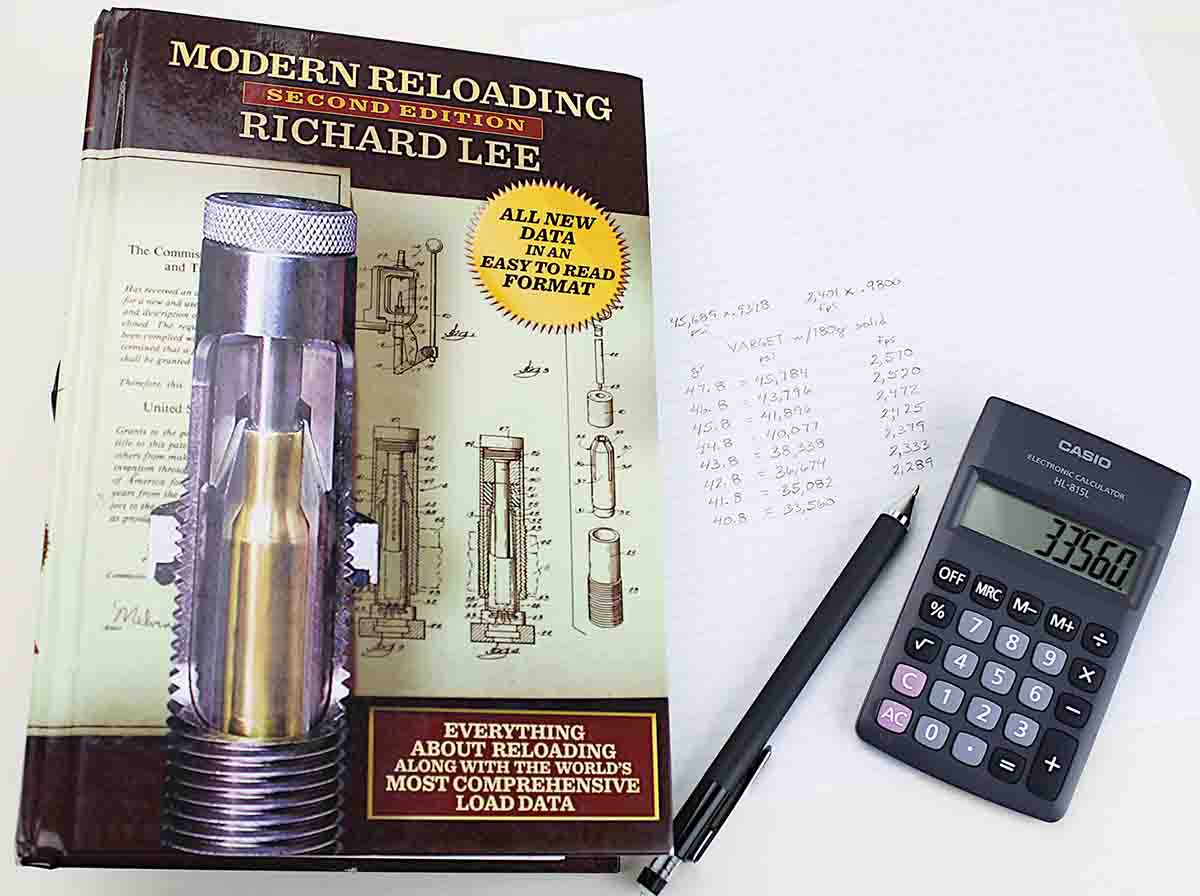

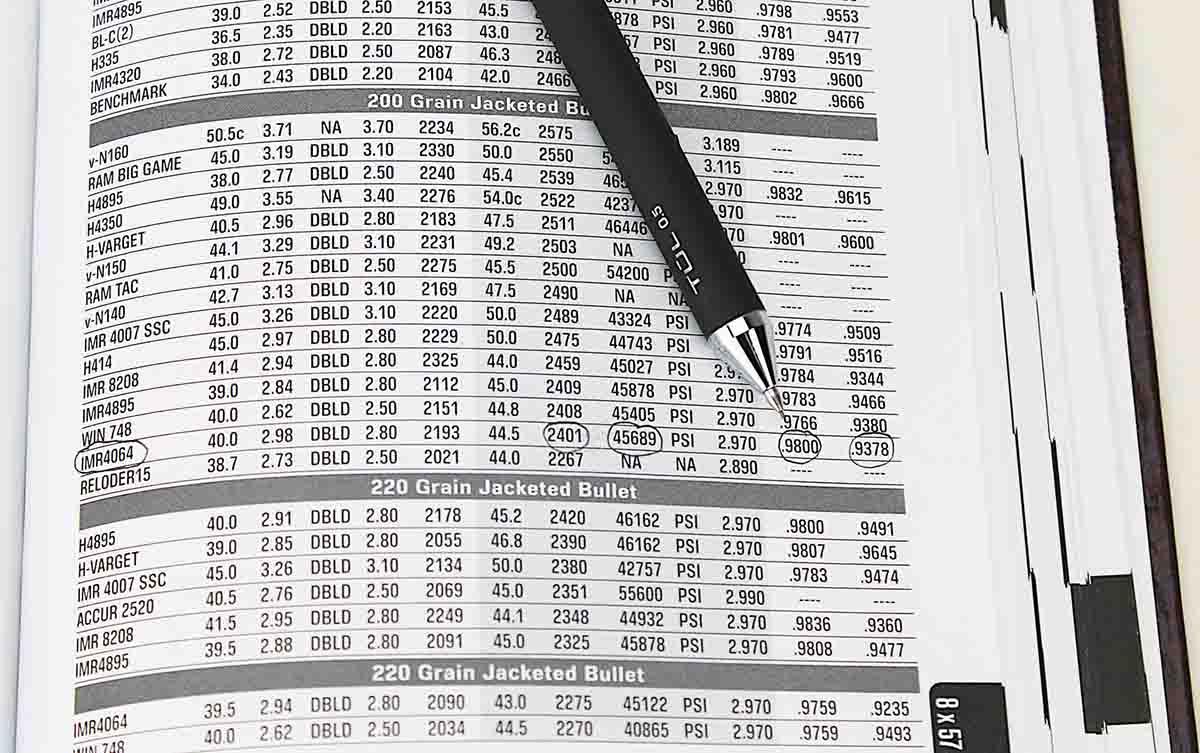

Modern load data specifically for the 8x57J is essentially nonexistent. Because the 8x57J utilizes the exact same case as the 8x57JS, and because .318 inch is mighty close to .323 inch, shooters can look to the 8x57JS for guidance, but they must be careful to keep estimated breech pressure well below 45,000 psi in deference to the Mauser-Mannlicher action design and age. Few reloading manuals list pressures, and simply assuming listed starting charges for nearly identical cartridges produce low-enough pressures can be a risky assumption. Modern Reloading Second Edition by Richard Lee, 2015, comes through as an excellent resource for delving into reloading the arcane 8x57J. For many cartridges among its load data, including the 8x57JS, Modern Reloading includes a “1 Grain Factor” that allows the handloader to estimate breech pressure with a simple calculator when stepping down a maximum powder charge one grain at a time with a specific powder and bullet weight.

Yes, pressures with the 8x57J .318-inch bullets will almost certainly be different than pressures listed for the 8x57JS .323-inch bullets – introducing any new variable to the loading equation will do that – but utilizing a chronograph and starting with charges estimated to produce about 35,000 psi, about 10,000 psi below the Mauser- Mannlicher action’s maximum, should keep reloaders out of trouble. Lee’s 1 Grain Factor will help us do that.

Bullets of .318-inch diameter are only slightly more common than altruism in politics. At this writing, Buffalo Arms Company has affordable jacketed softpoints of 150, 170 and 175 grains. Hawk, Inc. of New Jersey, makes a pair of hunters in 180- and 220-grain “round tip” configuration. Australian-bullet maker Woodleigh offers two, 200-grain, .318-inch bullets, a roundnose softnose and a PP SN (protected-point softnose); these are premium bullets retailing at nearly a dollar each. Hammer Bullets has a .318-inch, 185-grain bullet it calls the Hammer Hunter, a lathe-turned, pure copper bullet with a hollowpoint; lacking lead, it necessarily appears long for caliber. I ordered a sample packet of 15 of these Hammer Hunters to accompany the 200-grain Buffalo Arms jacketed softpoints I had on hand for testing.

Lee lists a starting charge of 40 grains of IMR-4064 with a 200-grain bullet delivering 2,193 fps in the 8x57JS, but what is the estimated pressure? Is it safe for the 8x57J in this old split receiver bridge action? To work Lee’s 1 Grain Factor, multiply the pressure given for the maximum listed charge with this bullet and powder combination (44.5 grains) by the constant .9378, which results in the estimated pressure generated by one grain less powder (43.5 grains). Note this figure of .9378 applies only to this bullet/powder/cartridge combination; do not attempt to apply it to any other combination.

Continue factoring in one-step increments until reduced to the desired pressure. As usual, pressure is inferred by bullet velocity measured with a chronograph, so the 1 Grain Factor also estimates bullet velocity in a similar manner (multiplying the maximum load velocity by the constant .9800).

Lee lists a maximum charge of 44.5 grains of IMR-4064 launching a 200-grain bullet at 2,401 fps and generating 45,689 psi in the 8x57JS. Applying Lee’s 1 Grain Factor to the maximum charge’s pressure, 45,689 x .9378, a one-grain charge reduction should result in 42,847 psi. Multiplying the maximum charge’s velocity of 2,401 fps by .9800 results in 2,352 fps. So, stepping down in one-grain increments with Lee’s 1 Grain Factor reduces estimated pressure and velocity as follows:

43.5 grains = 42,847 psi and 2,352 fps

42.5 grains = 40,182 psi and 2,305 fps

41.5 grains = 37,682 psi and 2,259 fps

40.5 grains = 35,338 psi and 2,214 fps

39.5 grains = 33,140 psi and 2,170 fps

38.5 grains = 31,079 psi and 2,126 fps

Lee’s 1 Grain Factor indicates the pressure for the published 8x57JS starting load of 40.5 grains of IMR-4064 is right at the maximum wanted for this 8x57J/Mauser-Mannlicher action combination, 35,000 psi. With this as a starting point, I loaded two test cartridges with 40 grains of IMR-4064 under the 200-grain bullets and fired those over a chronograph with resultant velocities of 2,061 and 2,067 fps, inferring a pressure just below 35,000 psi. Nice – now for the 185-grain bullet. Modern Reloading does not list that bullet weight, but it does list a 180-grain solid, so I used that data and Lee’s 1 Grain Factor for estimating pressure and velocity to establish a safe starting point with the 185-grain Hammer Hunter. Results for both powder and bullet combinations appear in the accompanying table and show that Lee’s 1 Grain Factor velocities are better than ballpark and so, as with all load data, pressures can be expected to be equally close to those as published. (Note the 185-grain Hammer bullets exceeded Lee’s velocity estimate with Varget for lighter 180-grain jacketed bullets. This is due to the Hammer’s solid copper construction.) Now with a place to begin and a method for estimating pressure, it’s safe to work up an accurate load.

The combination of the 8x57J cartridge and the Mauser-Mannlicher action make the Haenel- Mannlicher-style rifles fairly short-range propositions, especially as that split receiver bridge precludes common solutions for mounting a scope. A practiced marksman with excellent vision might take large game out to 300 yards with the iron-sighted rifle. But at that distance and started at 2,100 fps, a 170-grain bullet, for example, retains only about 561 foot-pounds of energy, well below the generally accepted guideline of 800 to 1,000 foot-pounds needed to reliably take a deer. Stepping up to a 220-grain bullet at 2,000 fps delivers about 1,167 foot-pounds at 300 yards – and at 42,800 psi edges the receiver’s pressure maximum of 45,000 psi. Shorten the range to 150/200 yards with the 220-grainer and elk-size game becomes a possibility at 1,400/1,500 foot-pounds. Heavy bullets and up-close shooting are apparently the real forte of the old cartridge and rifle.

Hunting, shooting and handloading aren’t always about maximum possible performance. Understanding firearms of the past through experience can bring shooters a greater appreciation for what we have today, and though we may never take it into the field, a Haenel-Mannlicher rifle and its obsolete cartridge are history in our hands, a connection to our grandfathers who hunted when it was cutting-edge firearms technology.

.jpg)