Cartridge Board

6.5x54mm Mannlicher-Schönauer

column By: Gil Sengel | April, 22

“You mean the year 1892?” asked the bureaucrat who had a major in history from a top American university. “Were there people here then?”

“Never mind,” said the boss, producing another secret algorithm and ordering, “Run this next, it will tell us how to end deficit spending.”

The bureaucrat rushed blindly away, flush with the knowledge he would now solve another history-altering problem. Suddenly, however, he realized he was in an undisclosed area of the undisclosed location and had no idea how to get back to his personal undisclosed location – obviously he never made it!

This may not be exactly how the new 6.5mm cartridges were created, but we do have insight into how their predecessors in the 1890s came about. Unlike today, where cartridge sizes are determined by a specific rifle design, the shape and caliber of early smokeless rounds were determined by the powders available.

Higher breech pressure came along with the new powders so they couldn’t simply replace black powder in existing military rounds. Cartridges and bullet diameters could, however, become smaller, but one thing that could not change was the result produced when the bullet struck its target. Keep in mind that all early smokeless powder and cartridge development was done by the militaries of national governments because of the cost.

At any rate, the first three smokeless military rounds (8mm Lebel, 7.92x57mm and .303 British) were essentially the same. All had bores of about 8mm, bullets of 180/200 grains weight pushed to 2,300/2,400 feet per second (fps). Obviously, this was far more power than needed for human soldiers. Then what were they intended to do?

Up until the middle of World War I, army transport in the field was by horse-drawn wagon. A few marksmen hiding along the enemies’ line-of-march could fire a few rounds killing a horse in each team. This would stop the movement of supplies or artillery to the front. Since there was no smoke-signature, the shooters could sneak away down the road and do it all again, provided their rifles were powerful enough.

A similar situation existed with the feared cavalry charge. There was little an infantryman could do against a guy mounted on a 900-pound horse swinging a saber. The only way to survive was to run or put the horse down quickly. This was probably similar to stopping the charge of a full-grown African lion. Heavy roundnose bullets from powerful rifles were required. Ever since firearms replaced swords and axes, governments have seen to it that their infantry troops were so armed.

Of interest is that the U.S. Navy adopted a 6mm round in 1895. It met the antipersonnel needs of ship protection when anchored in foreign ports and embassy protection. The navy didn’t have to repulse the cavalry charges!

As the first Romanian rifles were being built, some British gun writers and sportsmen were able to obtain these rifles and ammunition. This is strange because the performance of smokeless powder military rifles was a closely-guarded secret in most countries. Hunters immediately carried these guns and military ammunition to all parts of the Empire, killing everything that walked on four legs. Yes, this included lion, buffalo and elephant in Africa. The military lethality tests that selected the 6.5mm bullet of 160 grains were known to these sportsmen. So quickly popular did the 6.5x53mmR become that British gunmakers stopped using the millimeter designation, instead adopting the title .256 Mannlicher.

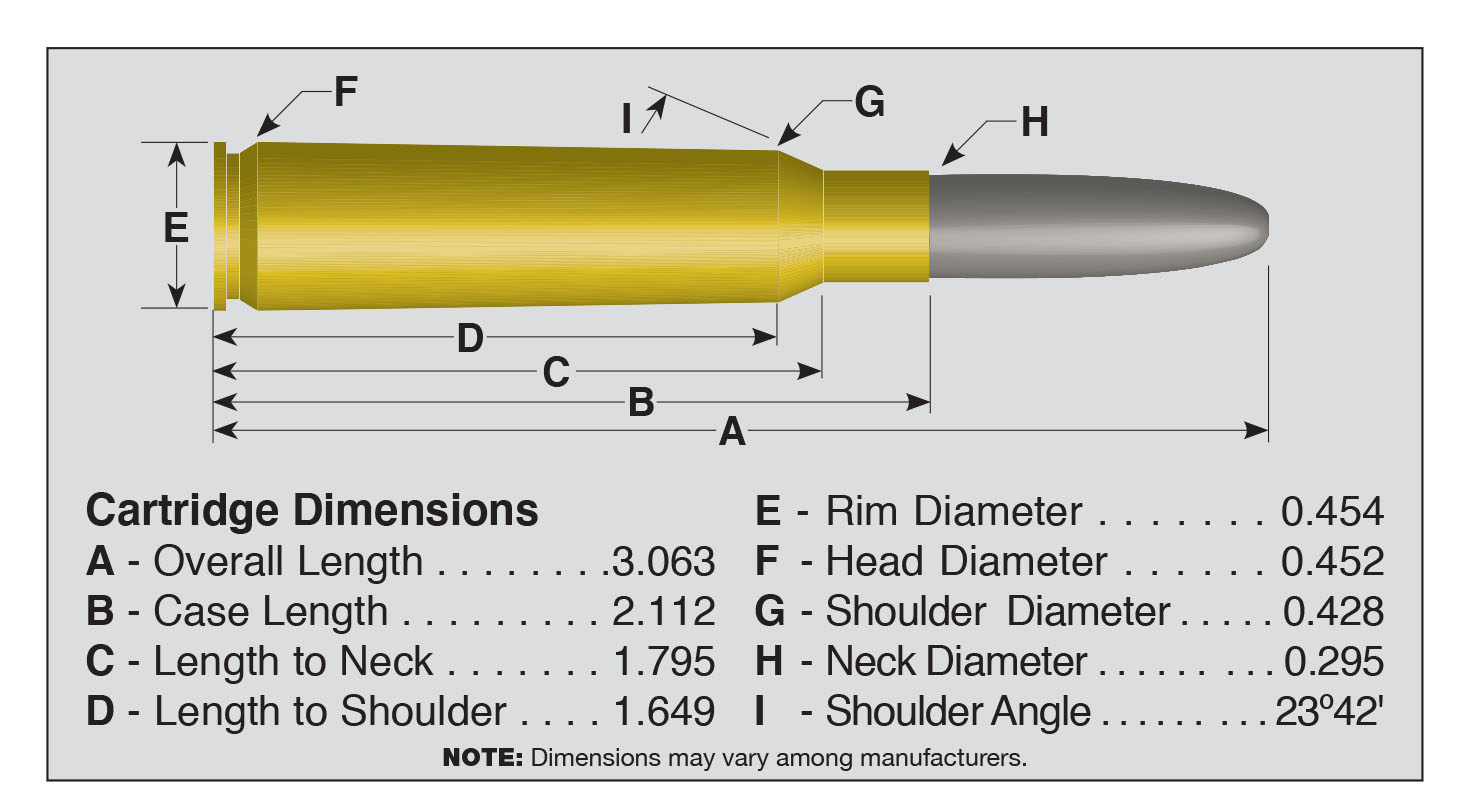

Thus, the stage was set for the 6.5x54mm Mannlicher-Schönauer (M-S). Otto Schönauer worked with Mannlicher at Steyr developing bolt-action military rifles. Around 1900, one of Mannlicher’s receivers was combined with Schönauer’s improved rotary magazine. This magazine was flush with the stock bottom instead of hanging down below it as did the five-round, in-line Mannlicher design. It did, however, require a rimless cartridge to function properly. Since the 6.5x53mmR was so popular in sporting circles, it was simply made in rimless form with no other changes, but was called 6.5x54mm to avoid confusion. In military guise, the rifle was called the M1903 Mannlicher, which appears to have only been adopted by the country of Greece. Steyr also introduced it as a hunting arm called the Mannlicher-Schönauer Sporting Carbine. It was an instant success.

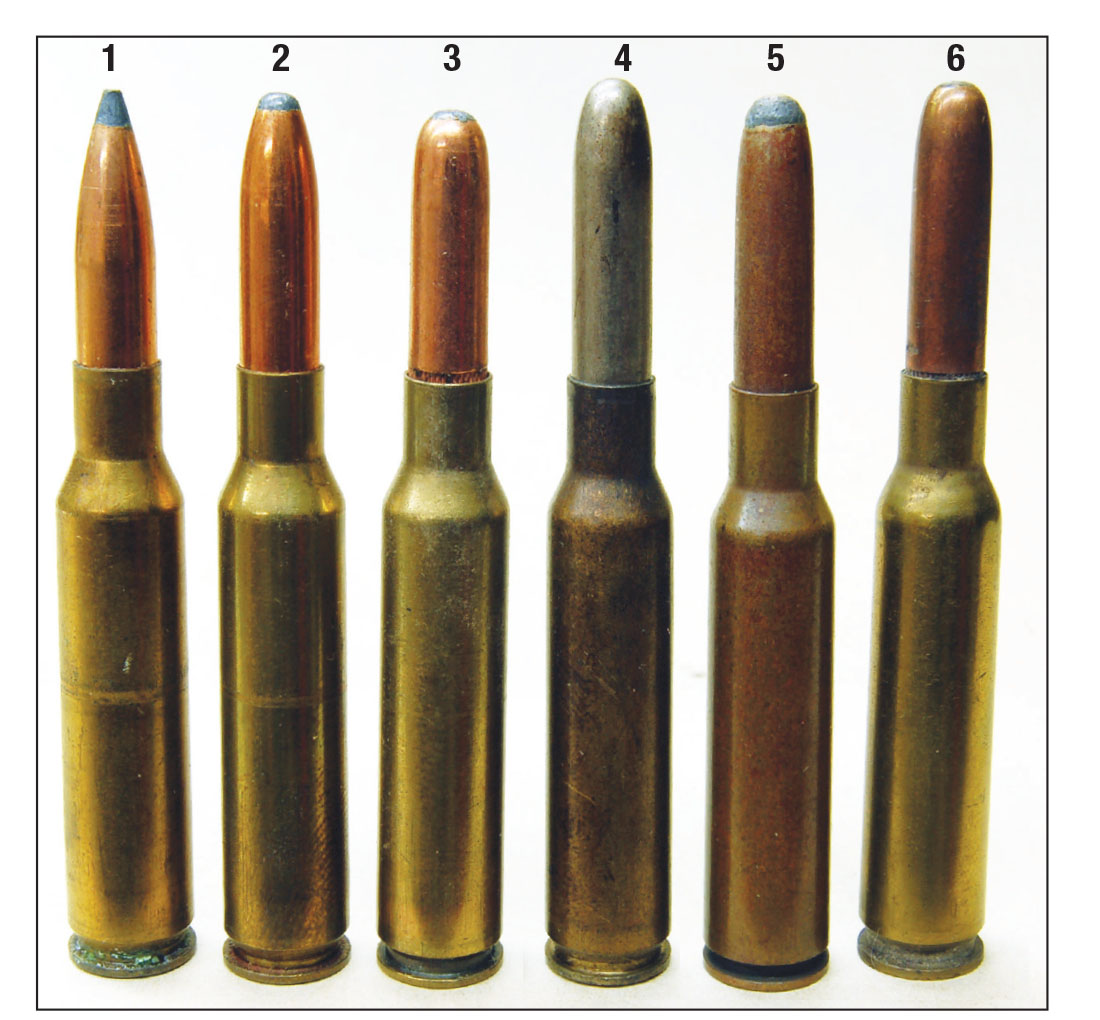

The little Steyr carbine featured a 17.7-inch barrel and weighed about 7 pounds. First ammunition was military loads using a 159- grain roundnose full jacket bullet rated at 2,350 fps (same as the 6.5x53mmR). The carbine was quickly carried to every part of the globe where wild game was hunted. This included Africa, where everything from plains game to elephant dropped to the long, hard bullet. No one was surprised because the 6.5x53mmR had already been there and done that!

Ammunition has since been loaded by most all European cartridge makers. Winchester and Remington even loaded it between World War I and World War II.

Today’s situation means it is wherever it can be found. The last I had was Norma.

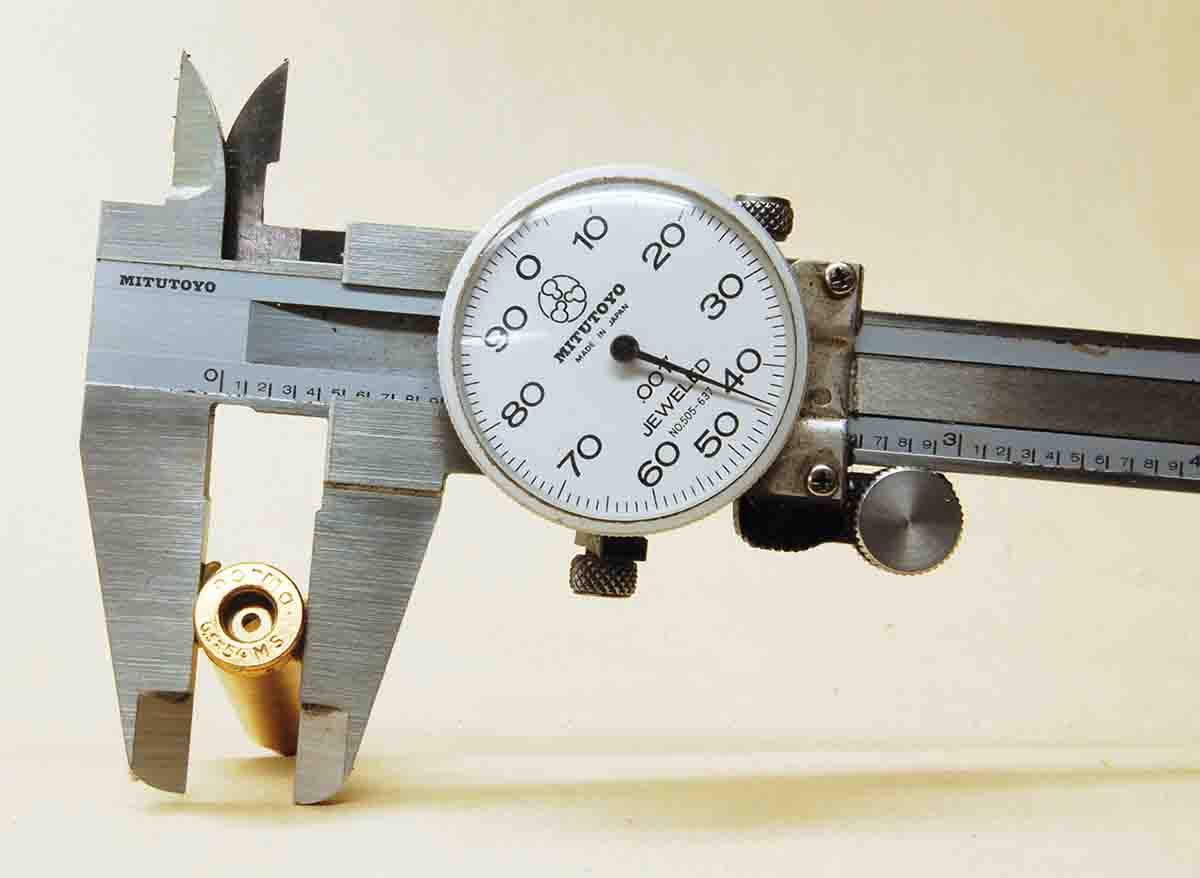

Those folks I know who handload for the 6.5x54mm all use Norma cases. Proper cases must be purchased because base size is smaller than, say, .30-06 and cannot be formed from anything else. Even though bullets from 124 to 160 grains are available, my own limited experience indicates only the 160 grain loaded to 2,200/2,300 fps in the carbine, produces good accuracy in the long chamber throat. This load yields 1,720/1,880 foot-pounds of energy at the muzzle, easily enough to take deer out to 200 yards, but I think it would be wise not to disturb lions. Fortunately, Hornady still lists its 160-grain softpoint. The iconic little M-S carbine and sporters built on Greek military rifles long ago can be happy for a long time to come.

.jpg)