All American .45s

Variations and Misconceptions

feature By: Mike Venturino Photos by Yvonne Venturino | April, 20

Almost 40 years ago when breaking into this business, I was thrilled to get an invitation to a writer gathering hosted by one of the major companies. One morning I was pitching an idea to this magazine’s then editor. As I spoke, a much older gent and

editor of other firearms magazines sitting nearby slapped his table and literally shouted at me: “I hate it when you young fellows call it .45 Long Colt! There never was a .45 Short Colt!” With what I considered great dignity, I calmly responded, “Okay, but can I finish talking about the .41 Long Colt?” The poor fellow was truly embarrassed, but all ended well. We became friendly and he gave me quite a few assignments thereafter.

With the knowledge I have all these years later, I wish that editor was still alive so I could inform him about two versions of “short” .45 Colt cartridges and several other .45 misconceptions.

Although the U.S. was not the only country to have .45-caliber handgun cartridges, we have had the largest variety. Both Colt and Smith & Wesson were responsible for their own .45 ideas, plus the ammunition maker Peters developed an offshoot of a Colt round and the U.S. government came up with another .45 Colt variation that only worked in some revolvers.

A fact that may surprise many readers is that the very first American .45-caliber metallic cartridge was not labeled as such. It was the .44 Colt, but in fact the barrel groove diameters of its revolvers were over .45 inch. How did such a mix-up come about? It was caused by the manner in which caliber designations were applied in those days. That was often by the diameter of a barrel’s bore.

For instance, Colt Model 1860 percussion revolvers all had bores smaller than .450 inch, but groove diameters were over that, hence they were known as .44s. For its Model 1871 Richards .44 Colt conversions, the company merely used barrels left over from manufacturing Model 1860 .44 percussion revolvers. Therefore, the Colt company called its first big-bore metallic handgun cartridge the .44 Colt. Factory loads varied. Bullets were usually around 208 to 212 grains, and powder charges varied from 23 to 28 grains.

By 1873, terminology had changed a bit because the new .45 Colt revolvers had barrel bore and groove diameters not identical to, but similar to, .44 Colts. However, the U.S. government decided that its new revolver cartridge would be .45, and so it was named.

At this point we need to cover one major .45 Colt misconception. It is often written that initial loads for .45 Colt included 40 grains of black powder under 255-grain (lead) bullets. The U.S. government began receiving its new Colt revolvers in November of 1873. A Frankford Arsenal .45 ammunition box dated two months later (January 1874) clearly states the load is 30 grains of powder with a 250-grain bullet. Commercial .45 Colt factory loads were heavier, but I’ve never encountered any documented information that in the 1873 to 1900 time frame any factory loads contained 40 grains of black powder.

Here’s another .45 Colt misconception. It has also been written that the .45 Colt served as the official U.S. Army revolver cartridge until 1892, when the .38 Colt was adopted. That’s not precisely so. As early as 1874, U.S. Army officials notified the Frankford Arsenal to discontinue manufacture of the “long” .45 in favor of a “short” version. That latter one was actually Smith & Wesson’s .45 developed for its top-break Model No. 3 revolver, commonly nicknamed “Schofield” today. Schofield cylinders were too short to accommodate the .45 Colt’s 1.60-inches overall cartridge length. Therefore, along with the Model No. 3, S&W designed a shorter round with an overall loaded length of 1.43 inches. Their cartridge cases were 1.29 inches and 1.10 inches, respectively. Also, the rim diameterof .45 Colt was .502 inch, and S&W’s round needed a .522-inch wide rim to function properly in the top break’s star-type extractor. In those days, the second .45 was often called the .45 Government.

All this happened because the U.S. Cavalry was receiving two .45 handguns: Colt’s solid frame single action and S&W’s top break. The shorter .45 Government could function perfectly in both revolvers, but not vice versa. This situation lasted until the early 1880s, when S&W’s No. 3 .45s were withdrawn from service and Frankford Arsenal production of .45 Government cartridges ceased. That arsenal returned to producing long .45s for the U.S. Army.

Military loads for .45 Government (aka .45 S&W, .45 Schofield) carried 28 grains of black powder with 230-grain bullets. Both Remington and Winchester later offered .45 S&W factory loads with 250-grain bullets and 30 grains of powder. Back in the 1870s the U.S. Army was evidently happy with low handgun velocities. With 28 to 30 grains of black powder and bullets from 230 to 250 grains, velocities from 7½-inch barrels ran in the 730- to 750-fps range. Incidentally, the .44 Colt with 210-grain bullets from 7½-inch barrels hit about 750 fps. These figures are not speculation. I’ve loaded and chronographed all.

The heaviest commercial .45 Colt factory load I’ve personally pinned down was in Winchester’s 1899 catalog. That was a 255-grain bullet over 38 grains of black powder. That one would have provided about 850 to 900 fps, depending on exact barrel length.

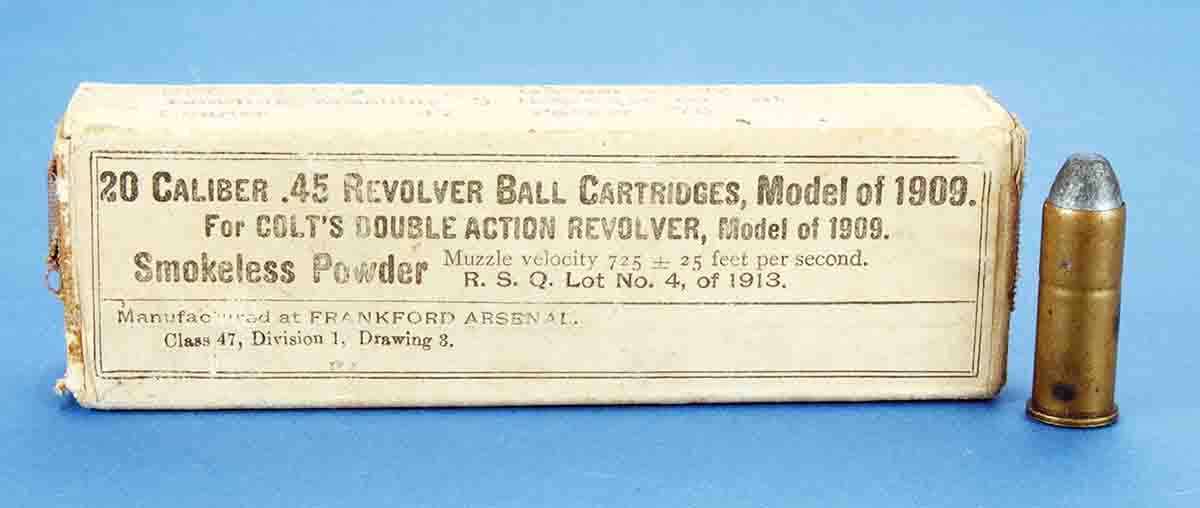

The U.S. government wasn’t quite done with .45 Colt in 1892. During the Philippine Insurrection of the early 1900s, thousands of .45 Colt single actions were withdrawn from storage and their 7½-inch barrels were cut to 5½ inches. As the story goes, the army’s .38s weren’t stopping drugged-up natives, so .45s were reissued. Then in 1909, even though the army was on the cusp of adopting a semiauto pistol, for a stop-gap measure it turned to Colt’s New Service .45 as the Model 1909. However, that tiny rim on early military and civilian .45 Colt cases was still a problem with star-type extractors. So the government went one better than the .45 S&W rim. Its .45 rounds issued specifically for the Model 1909 had rim diameters of .534 inch. Those cartridges could be fired in old single-action Colt .45s, but the rims were so wide they interfered with each other when put into neighboring chambers. Incidentally, my original box of Frankford Arsenal 1909 .45s lists muzzle velocity as 725 fps, plus or minus 25 fps.

One more .45 Colt misconception: It has often been written in firearms periodicals that Colt .45 barrel groove diameters between 1873 and 1941 were .454 inch. Yet when the model was resurrected in 1956, that dimension was reduced to .451 inch. Not so. As early as 1922, Colt listed .451/452 inch, minimum and maximum, for all .45 barrels. The Ideal Handbook No. 28 (1927) lists .452 inch as .45 Colt barrel groove diameter and .451 inch for .45 Auto.

Now back to the short/long .45 Colt controversy. As stated above, because .45 Government (.45 S&W, aka .45 Schofield) was used in .45 Colt revolvers, it could in the common vernacular be considered a “short” .45 Colt, but that’s not all. Remington-UMC did produce a short .45 Colt. It was headstamped .45 Colt but shared the .45 S&W’s 1.10-inch case length. What it did not share was the .45 S&W’s .522-inch rim diameter. Those UMC rounds had the almost negligible .502-inch .45 Colt rim diameter.

I have heard speculation that those were actually .45 S&W cartridges that were mislabeled .45 Colt. Nope, that’s not so either. I’ve had two original S&W Model No. 3 Schofields. I put those short .45 Colt rounds in their chambers and tried to eject them. About halfway up, the extractor slipped over that tiny rim and the cases dropped back into their chambers. The Remington-UMC boxes these short .45 Colt cartridges came in did not have “short” anywhere on them. However, a short .45 Colt cartridge existed in fact if not in name.

As early as 1905 Colt introduced a semiauto chambered for .45 Auto. Those early factory loads held 200-grain FMJ bullets instead of the later 230-grain versions. Comparative velocities were 910 fps and 800 fps, respectively. Today’s .45 Auto velocity is 830 fps for 230-grain FMJs. However, World War I boxes clearly state velocity as 800 fps with a plus/minus of 25 fps. Seems like the U.S. military liked staying in that 725- to 825 fps velocity range.

Just about every reader knows the story of how Colt and S&W supplied .45 Auto Model 1917 big frame revolvers in World War I. Extraction of rimless cases in revolver chambers was made possible by means of three-round, stamped steel “half-moon” clips. That worked fine for military purposes because empty cases were extracted and discarded in the field. Many post-war civilian

owners of Colt or S&W .45 Auto revolvers didn’t like fiddling with the clips. (I don’t either.) Therefore, as early as 1921 the Peters Ammunition Company introduced a .45 Auto-Rim. It was simply the basic .898-inch .45 Auto case fitted with a wide and thick rim. Although some factory loads in the past were loaded with FMJ bullets, for most of its existence .45 Auto- Rims predominately used lead alloy bullets. Most commonly they weighed 230 grains regardless of composition.

In handguns of similar strength, .45 Auto-Rims can be loaded to equal .45 Colt velocities with similar weight bullets. Powder capacity of the .45 Colt is much greater due to the fact that it was developed for black powder, and of course equally potent charges of smokeless powder require much less space. If a shooter is already handloading for .45 Auto, all that is required for .45 Auto-Rim handloading is a proper shell holder for the rimmed round.

Taking a look at .45 bullets for reloading, if they are suitable for .45 Auto they will be okay for .45 Auto-Rim. If they are okay for .45 Auto/.45 Auto-Rim, they will be okay for .45 S&W and .45 Colt. The reverse is not so cut-and-dry because 250-grain and heavier .45 bullets will raise pressures in the smaller cases. Their necessarily deeper seating depths reduce powder space. Except for very early Colt .45 revolvers with barrel grooves of .454 inch, bullets of .451 and .452 inch are correct for all modern .45s. With my personal handloading, almost all revolver-destined .45s get lead alloy bullets. So do my 1917 and 1918 vintage .45s, which will be mentioned again. Modern .45 semiautos are usually fed FMJs. (World War II vintage M1 and M3 .45 Auto submachine guns are very valuable, so I like to save wear on their barrels by using lead alloy bullets.)

Powders for all the .45s are likewise fairly interchangeable. From Bullseye to Unique, most any propellant works well. Best accuracy in .45 Colt and .45 Auto-Rim has been with Red Dot, and I’ve had great results with W-231 and Hodgdon HP38 with all of them. One might think that Hodgdon’s Trail Boss would not be suitable for the small capacity .45 Auto/Auto-Rim. Not so. I developed a fine, albeit mild, Trail Boss .45 Auto load for my World War I vintage Colt 1911s. There’s no reason to strain 100-plus-year-old pistols.

Let’s play the “if you could only have one” game for a bit. If I could only have one .45 handgun, it would be a single action with both .45 Colt and .45 Auto cylinders. On the other hand, if I could only have one .45 cartridge it would have to be .45 Auto-Rim. If only one bullet mould was permissible for all my .45s, it would have to be RCBS 45-230 CM. It may have a wide flatnose, but it functions perfectly in all my 1911-type pistols. If only allowed one propellant, I’d pick Red Dot due to its accuracy potential, or perhaps Trail Boss because it’s virtually impossible to double charge a case.

My .45 Colt and .45 Auto reloading began in 1968, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that I tackled the .45 Auto-Rim and .45 S&W. By my hand-jotted notes, I’ve owned 92 .45 pistols and revolvers. M1 (Thompson) and M3 (grease gun) submachine guns have been in the mix. All were fired primarily with handloads and mostly with cast bullets. If there is an All American caliber, it is .45.

.jpg)