America and the .32 Revolver

Shooting Five Classic Cartridges

feature By: Gil Sengel | September, 22

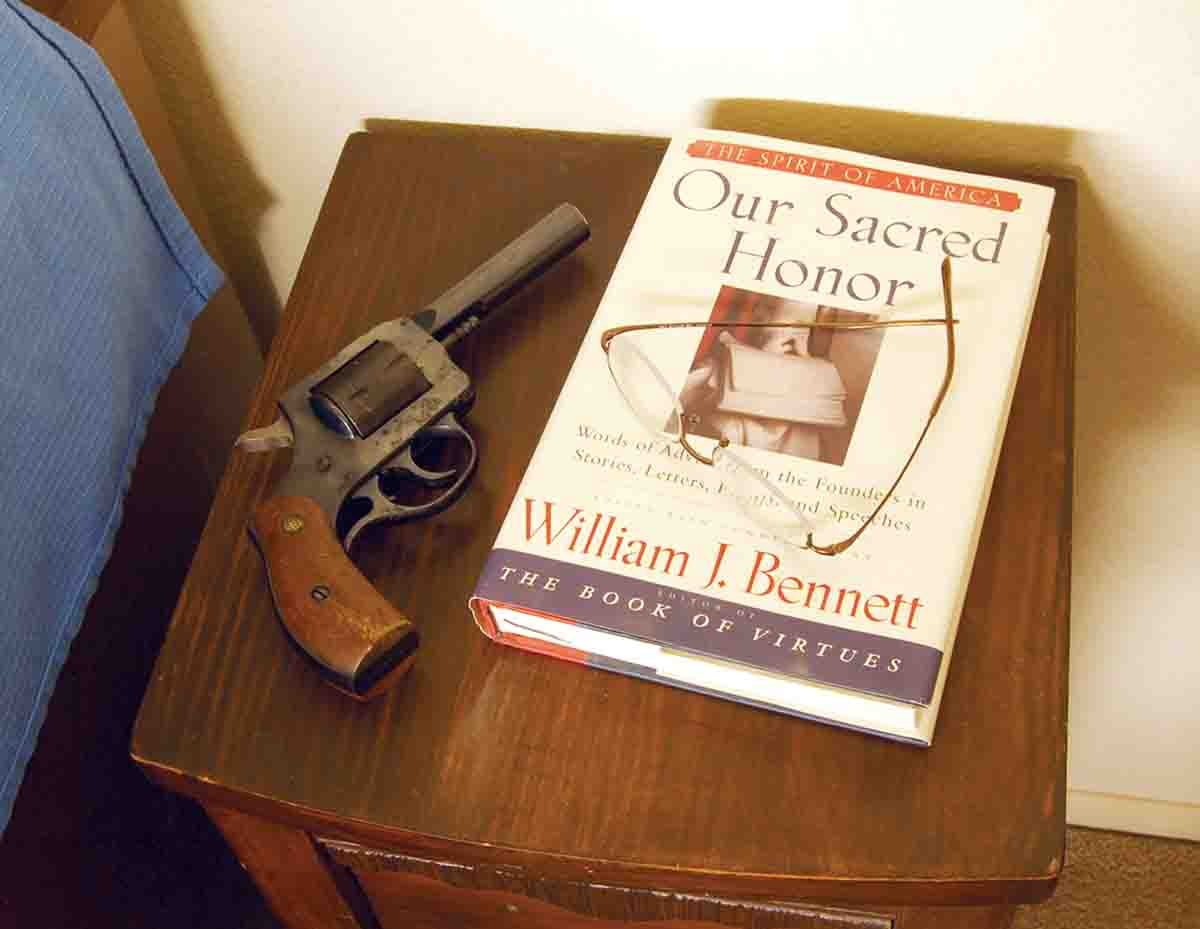

Such history is exposed when we look at the story of America’s so-called .32-caliber revolvers. It began with Samuel Colt’s small .31-caliber percussion pocket pistols. Collectors tell me that the guns fired a .310-inch diameter roundball (which would make it only about .30 caliber). By 1857, Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson had created the .22 Short rimfire. Then, in 1861, the .32 rimfire appeared, which became the .32 Long rimfire when a shorter-cased version (.32 Short rimfire) was loaded for very small pocket pistols beginning in the mid-1860s.

.32 S&W

By 1899, Harrington & Richardson was offering 10 revolver models in 23 variations for the .32 S&W. Iver Johnson had sold three million in the chambering by 1910. Even Sears, Roebuck and Co., sold 13 models in 1908, including S&W, Colt, imports and house brand A.J. Aubrey.

All of this puts doubt into our American history. There was absolutely no purpose for these millions of inexpensive .32s other than personal self-defense. None – and, yes, I am familiar with the term “Saturday night special,” indicating a criminal would buy the cheapest handgun he could find to use in burglaries and Saturday night robberies when folks who worked six-day weeks got paid. Absurd. Why wouldn’t the gun just be stolen in the normal course of activities, in which case, it could as well be a .45 Colt or .44 S&W as a .32 Iver Johnson?

Given that these early guns were made in the U.S. by the millions and imported in seemingly equal numbers, it’s not surprising they are commonly seen today. Almost all are of hinged-frame design. In other words, when a lock at the top of the frame is released, barrel and cylinder pivot up like a double shotgun. If bore and chamber are not pitted, it is great fun to shoot them a little. As handloaders, we can do this.

The original load for the .32 S&W was an 85-grain lead bullet ahead of a case full of fine black powder. Muzzle velocity was said to be in the 600/650 feet per second (fps) range. Early smokeless loadings use the same bullet at 650/680 fps.

Surprisingly, Lyman still sells the proper mould for the .32 S&W. It is number 313249. Mine drops an 84-grain bullet when cast of pure lead and unsized, using Lee Liquid Alox. The 3-inch Iver Johnson shown in the photo only gives 435 fps from a Starline case full of GOEX FFFg and 462 fps using Pyrodex P. Table I shows this as well as load data for smokeless powders collected over the years from sources who insist it is maximum for break-open guns.

.jpg)

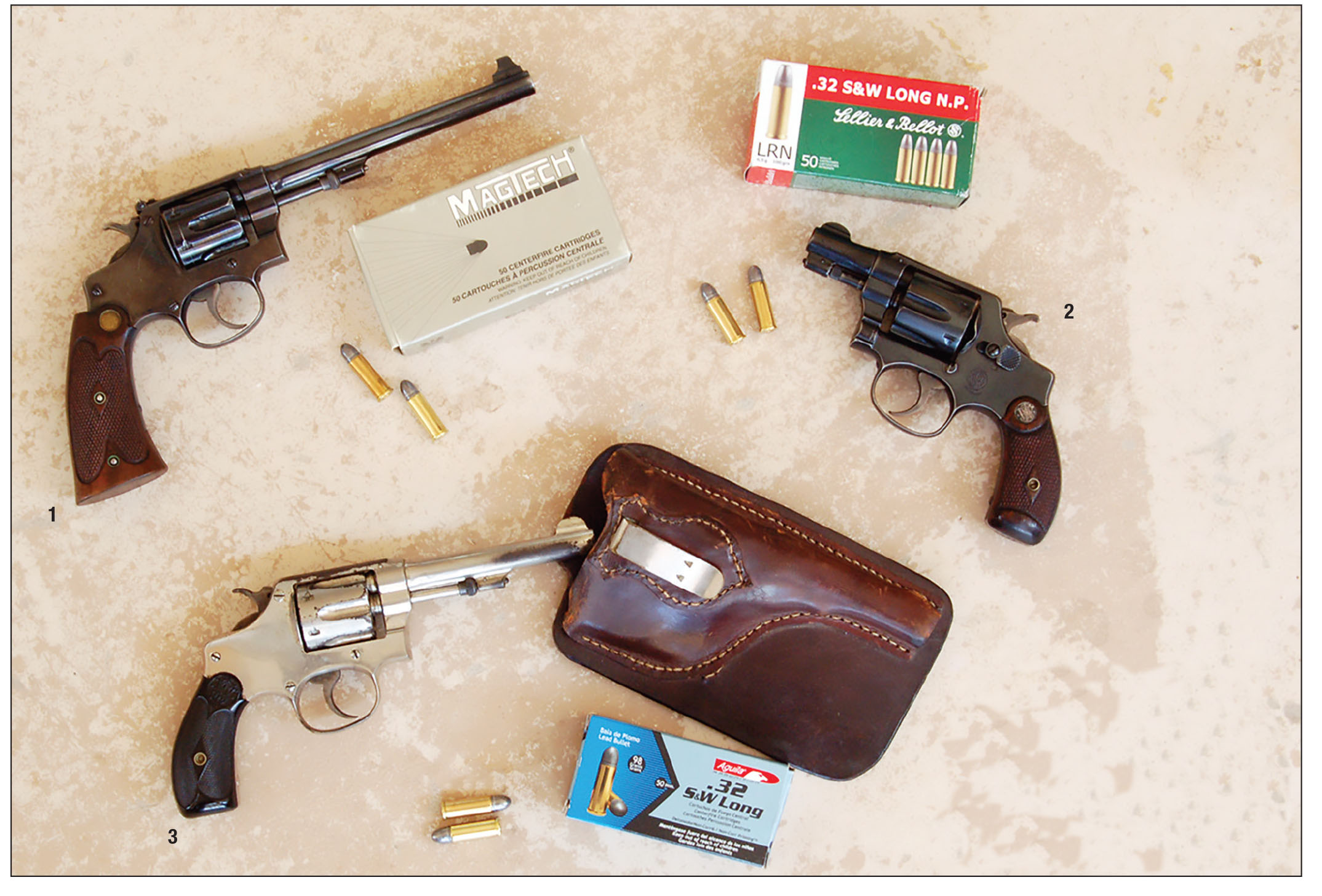

.32 S&W Long

A few more powerful .32 revolver rounds appeared in the 1880s. They were either outside lubed or chambered in revolvers that did not become popular. This changed in 1896 when S&W lengthened its old, .32 S&W case to .910 inch and increased its bullet weight to 98 grains. The cartridge was called .32 S&W Long.

Citizens bought countless revolvers for the .32 S&W Long, as did metropolitan police departments. Thus, these used guns are easy to find today. Early Colts and S&Ws were built on small frames like .22 rimfires and so they are a bit hard to shoot accurately for anyone with large hands. The pick of the litter is the S&W K-32 built on the larger K-frame. If there is a finer centerfire plinker and small-game revolver, I don’t know what it could be. An S&W 6-inch Hand Ejector of 1907 was used for Table II.

.jpg)

.32-20 Winchester

.jpg)

Something rather strange happened in the history of .32 revolvers in 1899. That year, S&W introduced the .38 S&W Special cartridge and a heavier frame revolver with longer cylinder to accommodate it. This same gun was also chambered in .32-20 Winchester (.32 WCF), a rifle round originally designed for the Winchester M73 rifle in 1882. Colt did the same the following year. The reason for doing so is far from clear. The bullet weight was 115 grains and muzzle velocity about 1,000 fps from a 6-inch barrel, raising energy some 65 percent over the .32 Long.

The bullet used was Lyman’s copy of the factory slug, 115-grain No. 311008; the mould is still listed. Commercial cast bullets from this mould are also readily available. If using other data, be certain it does not exceed The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) maximum pressure of 16,000 CUP. Do not use data for T/C Contender! Loaded to 1910 specifications, the .32-20 performs much like our next American .32 round. Current .32-20 factory loads, however, are significantly reduced.

.jpg)

.32 H&R Magnum

After nearly 106 years of existence, it seemed that America’s smallest centerfire revolver would soon be forgotten. Then, 1984 saw Harrington & Richardson Arms (H&R) begin selling its lightweight, inexpensive

revolvers firing a new cartridge called the .32 H&R Magnum. The round was a joint venture of Federal Cartridge and H&R. It was also the first new round in a long time to fill a real need, even though it didn’t blow paint off the walls or cause instant hearing loss. Modern gun writers didn’t know what to make of it. They called it “underpowered.”

The .32 H&R is not intended to shoot through auto bodies, 10 sheets of drywall or 28 inches of Jell-O.

It’s also not intended for 50 yards or even 25 yards, but rather 25 feet. Both the H&R revolver and the recoil produced are light enough to be handled by most anyone. H&R guns are dead reliable and cost one-third or less of other brands. A textbook example of a win-win situation for home protection.

Most all makers of revolvers sold at least one model chambered for the .32 H&R. The gun used here was an original H&R with a 4-inch barrel. It easily delivered 1½-inch groups at 30 feet, perfect for its intended purpose. Loads shown in Table IV were shot in the original H&R loaned by friend John Gannaway, who also provided some of the others pictured. There is much data available, but be careful here. Pressure limit for the .32 H&R is 21,000 CUP, well below the .357 Magnum in deference to the light H&R revolvers. Much data is intended for stronger guns. Be certain of the pressure before using.

.jpg)

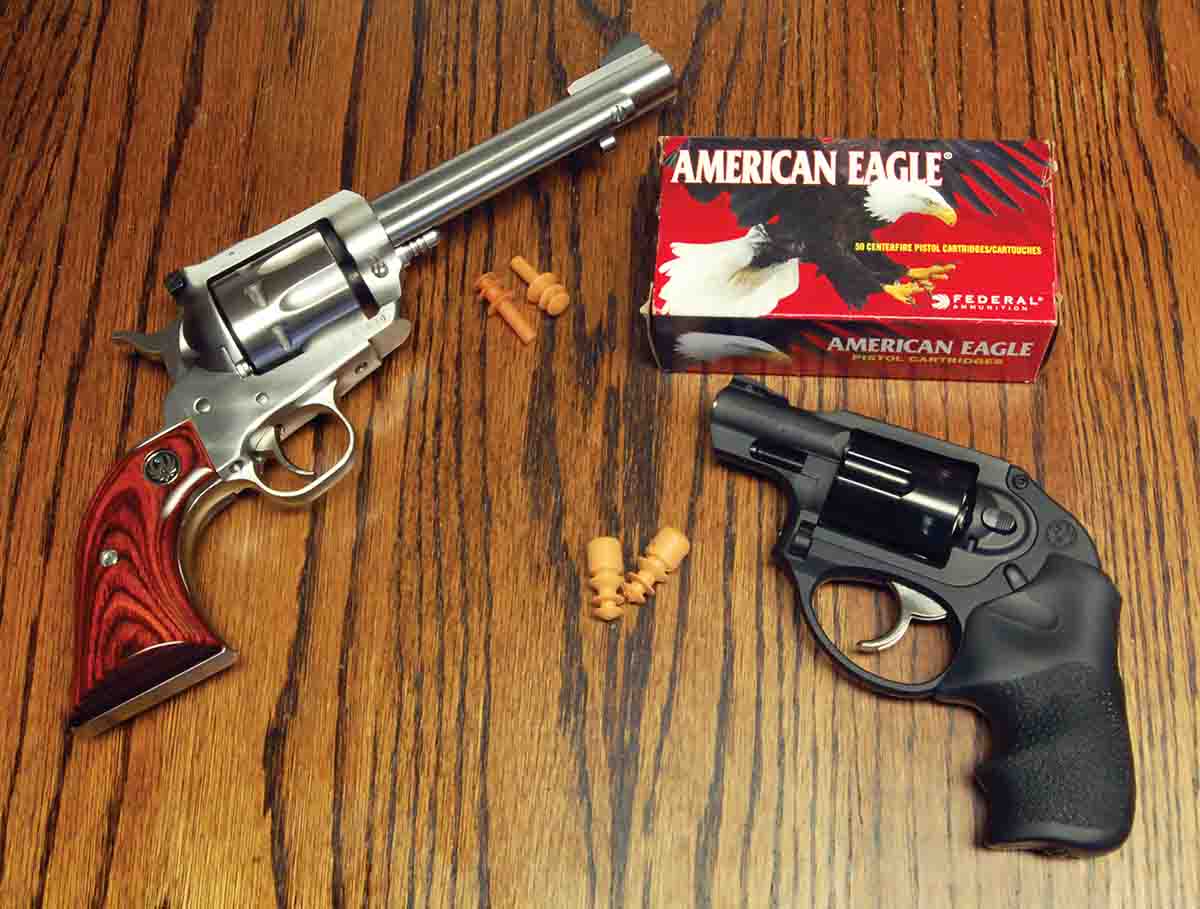

.327 Federal Magnum

After the “experts” opined that the .32 H&R was underpowered, the appearance of the .327 Federal was a foregone conclusion. In 2007, it became reality. By stretching the .32 H&R case .125 inch and vastly increasing breech pressure (45,000 psi), muzzle velocities from 4-inch barrels were advertised as 1,400/1,500 fps for various 85/100-grain bullets. Now, according to the experts, we had a useful revolver cartridge!

The 8-shot Ruger Blackhawk is much better. It shot the loads for Table V. Here is a handgun giving higher velocities than the original .32-20 did from a rifle. It’s 51-ounce weight reduces recoil to a manageable degree for most folks. It’s still not enjoyable. Sniping at tip-over steel silhouettes at 100 to 150 yards is fun for a while. Some will like it, but the blast and small caliber make it questionable for hunting and single-action revolvers are questionable for home defense for about a dozen reasons.

Thus, we come to the end of America’s popular so-called .32-caliber revolvers. All but the last one are a part of the history of self-defense handguns that is never told today. With loading dies, Starline brass and other components commonly available, handloaders can experience shooting a real piece of history – despite what today’s historians say.

.jpg)