Mike’s Shootin’ Shack

Favorite Casting Alloy

column By: Mike Venturino - Photos by Yvonne Venturino | September, 22

When my bullet casting career started in 1966, lead alloys were abundant. Besides the ubiquitous wheel weights, old sheet roofing, lead plumbing pipes and plain old scrap alloy were cheap and plentiful. Additionally, advances in printing caused newspapers to begin disposing of Linotype albeit its cost was a bit more than scrap alloys. Back in those days, if it melted in my lead furnace and something resembling bullets dropped from moulds it was shot.

My small hometown had a prosperous Western Auto store. In the late 1960s, I made a deal with its owner. If he would save his used wheel weights for me, I would buy all he saved at $6 per 5-gallon bucket. That was roughly 100 pounds and he kept me well supplied. For example: one college spring break, being too poor to head to a warm beach, I stayed home and cast 12,000 handgun bullets – .38s, .41s, .44s and .45s.

However, upon moving to Montana in the early 1970s, I neglected advising the Western Auto fellow of my leaving. At Christmas time in 1977, when back in West Virginia for a family visit and when walking down the street, I encountered the Western Auto owner. He said, “I wish you would come get those wheel weights. My storage shed is getting full.” Driving back to Montana, my pickup’s mileage was poor because of the half-ton or so wheel weights in the back.

Now fast forward about 15 years. That’s when I gave a friend three 5-gallon buckets of wheel weights just to get them out of my storage shed. (They didn’t come from West Virginia. That half-ton had long been shot away.)

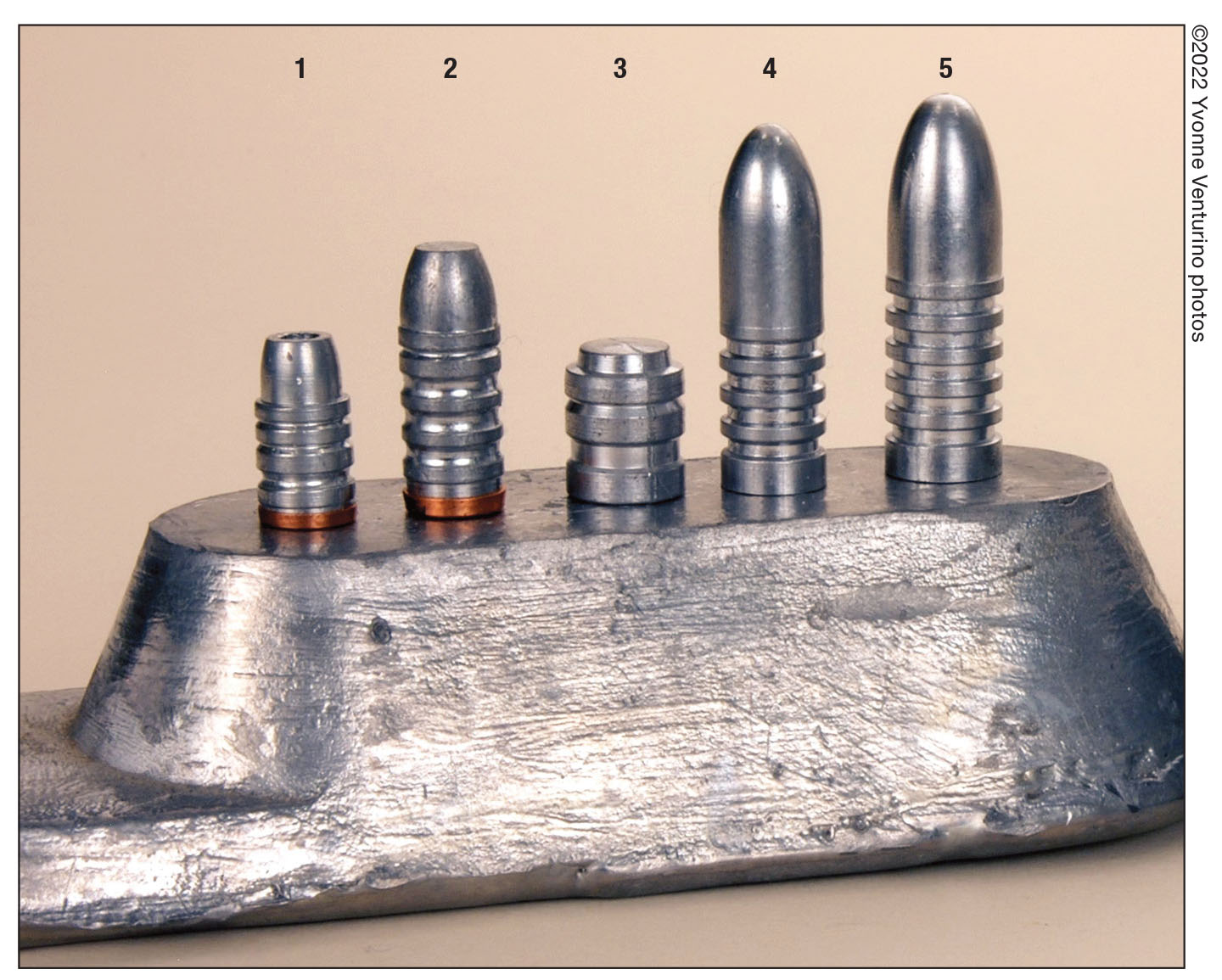

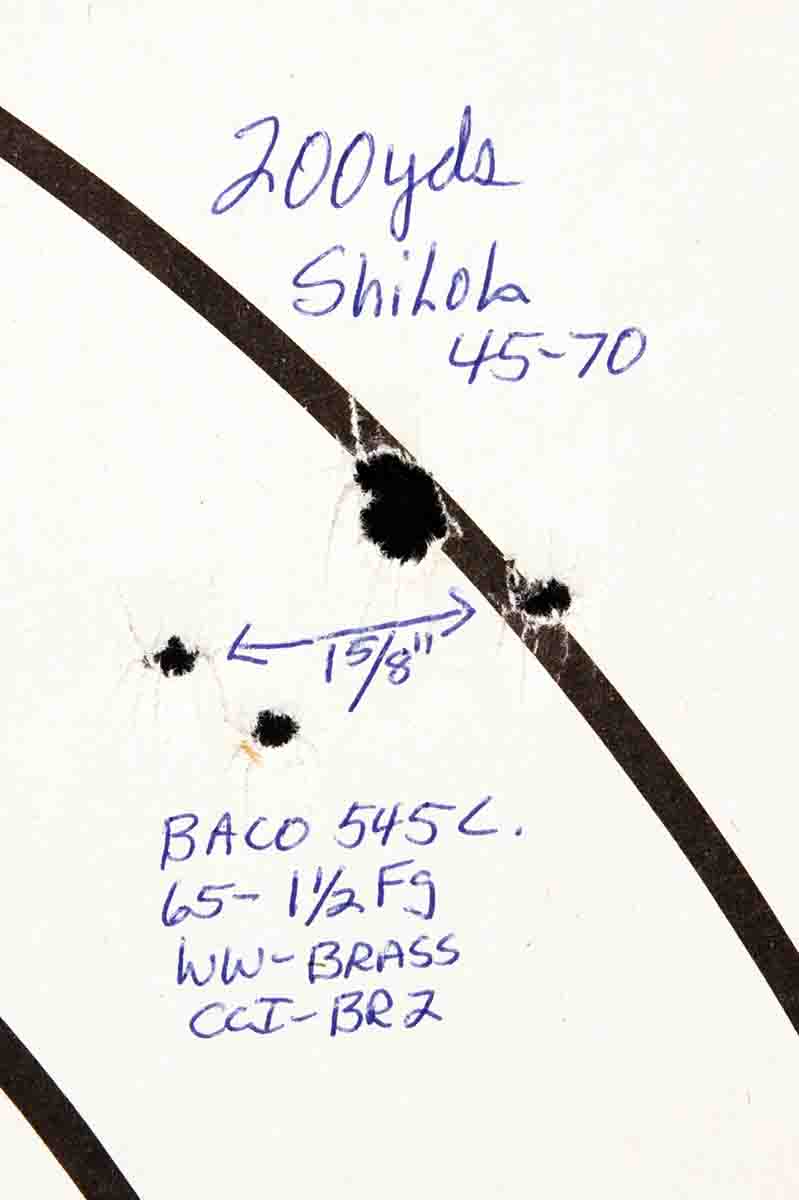

Why the change of heart? It stemmed from my near obsession with the then new NRA game of Black Powder Cartridge Rifle Silhouette (BPCR). After a few years of avid participation, I was faced with the fact that my scores varied from decent to poor. Also, my rifle barrels occasionally lead-fouled badly. Until then, I had relied on the usual hard blend of wheel weights with a little tin added to the lead pot. That roughly equaled Lyman’s formula for No. 2 alloy. At that time, I was using a RN/FP .40-caliber bullet nominally weighing 400 grains. Trying to figure out my problem, bullets from different casting sessions were weighed. They varied from 395 to 410 grains and I blithely did not bother to keep the batches separated. Obviously, my lack of consistency in mixing alloys was at fault. No wonder I was missing many of the 500-meter ram targets with dimensions from belly to backbone of only 12 inches.

Decades back, Elmer Keith wrote that for ordinary revolver cartridges, he recommended a blend of one part tin to 16 parts lead. For magnum revolver shooting, he used a “harder” blend of one part tin to 10 parts lead. Lyman’s various reloading and casting handbooks shows that 1:16 alloy is rated 11 on the Brinell Hardness (BHN) scale and 1:10 only a tiny bit harder at 11.5. (Lyman No. 2 alloy formula is rated at 15 BHN.) The blend of 1:20 rated 10, so with hundreds of pounds of that alloy on hand, I began trying them for revolver bullets. Results were superlative. Almost always, they shot very clean – as in little or no lead fouling. I will admit that with higher velocities, a gas check bullet design is preferable.

Another reason I gave away those buckets of wheel weights is that modern ones are no longer trustworthy. Never was a problem experienced with wheel weights back in those early years. They were melted outdoors, clips disposed, fluxed heavily to remove road grit and cast into ingots. Now some (or all) wheel weights are being imported and can contain mystery metals. Bullet casting friends have related that when some new wheel weights are added to a pot of good alloy, it is tainted. Bullets don’t fill out or have obvious voids.

Metals such as lead and tin can be found on eBay, but I’d rather trust better known sources for alloy now. Lead foundries have all but died out in the U.S., but there are still plenty of businesses selling shooters’ alloy. The well-known companies of Buffalo Arms, Graf & Sons and

MidwayUSA sell blended alloys and pure lead. John Walters, a long-time silhouette shooting friend (thetin wadman@cox.net) sells tin, pure lead or blended alloys. I’ve shot well over a half-ton of his product with nary a complaint. Surely, there are more sellers of which I’m not aware.

Not all my shooting is done with 1:20 (tin to lead) alloy, but it is used in the greater bulk of my casting. (Some shooting projects require the use of Linotype or pure lead but that’s fodder for another column.) However, a few hundred pounds of roofing lead and a few dozen bars of 50/50 tin-lead solder are kept on hand – just in case. I don’t plan to ever be without bullets.