Black-Powder Cartridge Target Bullets

Fine-Tuning for Accuracy

feature By: Mike Venturino | October, 21

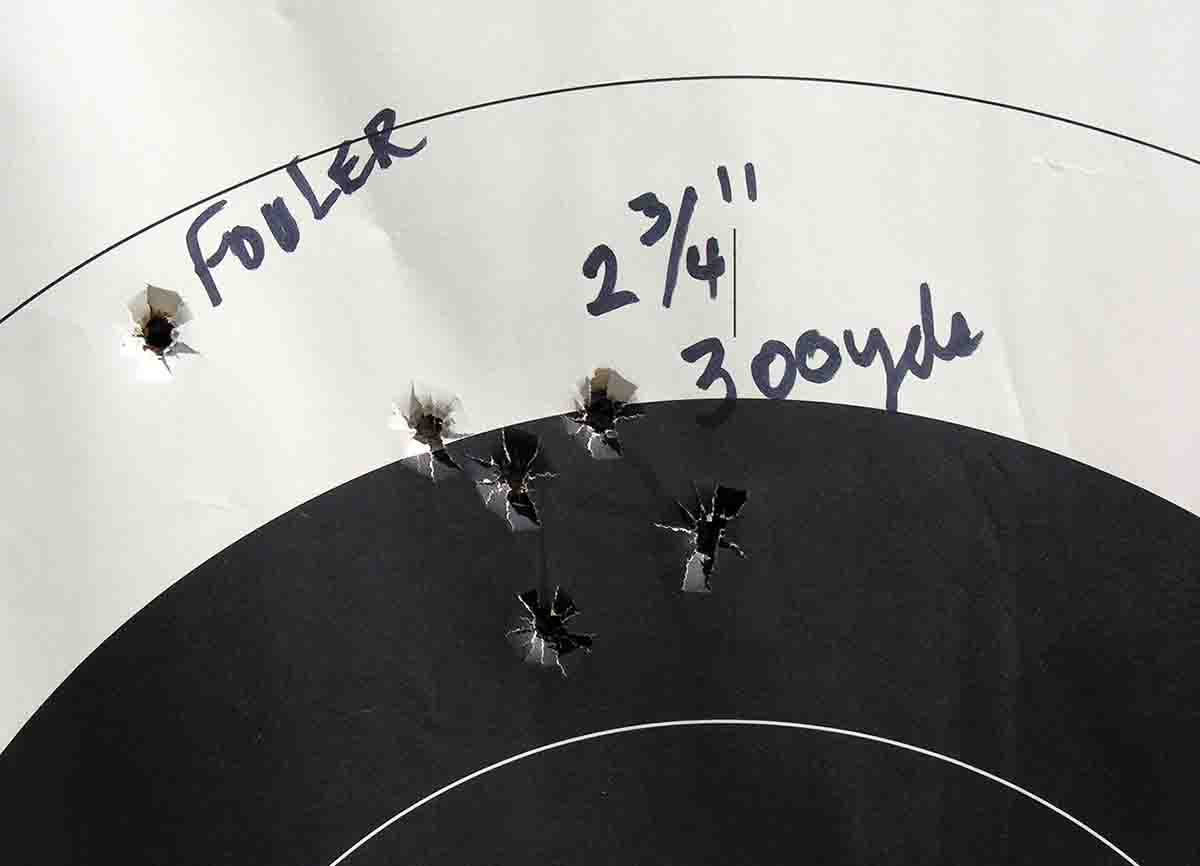

Before getting into bullet details, I’d like to briefly describe the demands of each type of competition. NRA BPCR Silhouette and BP Target (paper) games require precision. In the former, metallic targets are at 200 (chickens), 300 (pigs) 385 (turkeys) and 500 (rams). That’s in meters, with chickens shot offhand and the rest from sitting or prone with a crossed stick rest. The silhouette size details are too lengthy to cover here, so I’ll suffice it to say that rifles and handloads must be capable of less than 2 minute-of-angle (MOA) groups to be competitive. Paper targets for NRA BP Long Range at 800, 900 and 1,000 yards have a 20-inch, 10-ring with 10-inch X-ring. Likewise, they are fired at from sitting or prone with a cross stick rest. Accuracy requirements to be competitive are at least as stringent for this game as silhouette – probably more so.

The cast bullet alloy maxim I grew up with as a smokeless powder shooter was that harder was better. Lyman lists all its cataloged bullet weights as poured from its No. 2 alloy blend with a Brinell Hardness Number (BHN) of 15. Linotype has a 22 BHN. Conversely, my chosen alloy for black-powder cartridges is 1:20 (tin-to-lead) alloy with a BHN of 10. Many very successful competitors use even softer bullets of a 1:30 to 1:40 (tin-to-lead) mix. The BHN of the latter alloy is 8.5. (Note: These BHN numbers are borrowed from the Lyman 50th Edition Reloading Handbook, 2016.)

Smokeless powders ignite when fired and burn progressively as they pass down the barrel. How long their burn lasts depends on how “fast” or “slow” the propellant burns. Conversely, black powder is a low yield explosive. When ignited, it goes all at once, giving an explosive whack to the bullet’s base. Softer bullets obturate, i.e. swell to seal in rifle chamber leades. Thusly, they prevent gas blowby, which causes lead particle transfer from the edge of bullet bases to barrel interiors. Hard bullets don’t obturate as easily, hence contrary to most cast bullet logic, they lead foul badly when coupled with black powder. I know a passel of high-placing BPCR Silhouette competitors nationwide and have learned of none using antimony in their alloy blends.

There’s a side effect in BPCR cartridges with soft and long bullets, which is important when picking a cast bullet design. That is bullet nose slump. Significantly undersize, soft alloy, cast bullet noses will slump to one side or the other when bullet bases are slapped violently by black powder’s explosion. Here’s an example I experienced long ago. I had two Lyman moulds; both numbers 457125 listed as 500 grains of Lyman No. 2 alloy. Cast of 1:20 alloy, one shot very well from my Shiloh Sharps Model 1874 .45-70. From the same alloy, that other mould’s bullets all tumbled. Gaining some experience, I measured their noses. The good one’s nose measured .448 inch. The bad one’s nose measured .439 inch. The rifle’s barrel groove and land diameter was .458 inch/.450 inch. Upon firing, the .439-inch nose was actually bending. Bullets recovered showed rifling grooves only along one side of bullet noses. (I wish some of those bullets had been saved for photography.)

Now let’s consider bullet lubrication. Cast bullet designs from the late 1800s differ radically from those appearing in the twentieth- century. Earlier types had very wide and deep lube grooves, and many of them. Often, they were square at the grooves’ bottoms. Bullets designed in the smokeless powder era, especially in the last 50 years, generally have fewer grooves that are shallow, rounded at their bottoms and pencil line wide.

When I started casting in the mid-1960s, bullet lubes were universally soft, perhaps not putty soft, but still malleable at room temperature. Over the years, hard lubricants arrived; so hard at room temperature that heaters were devised to fit under lube/sizing machines. Hard lubes became even more popular when laws changed so that shooters could have their bullets shipped to them in bulk. A box of 500 hard-lubed cast bullets will arrive with the lube partially, or even fully, displaced from a modest number of bullets. Bullets shipped with softer lubes will arrive with lube everywhere except in grooves.

However, a significant reason bullet lubes changed over time was their purpose. With smokeless powders, bullet lubes are meant to prevent leading, period. All cast bullet shooters understand that leading can be ruinous to accuracy, not to mention difficult to remove. Black-powder lubes share that purpose but also have another, perhaps even more important chore. Black-powder bullet lubes must keep fouling soft. There’s a very simple test to determine if a black-powder bullet lube is doing its job. After firing a few rounds, run a finger over the firearm’s muzzle (unloaded of course). If the fouling is greasy, all is well. If fouling is hard, the lube isn’t working. With that in mind, most BPCR shooters want large lube grooves and sometimes plenty of them.

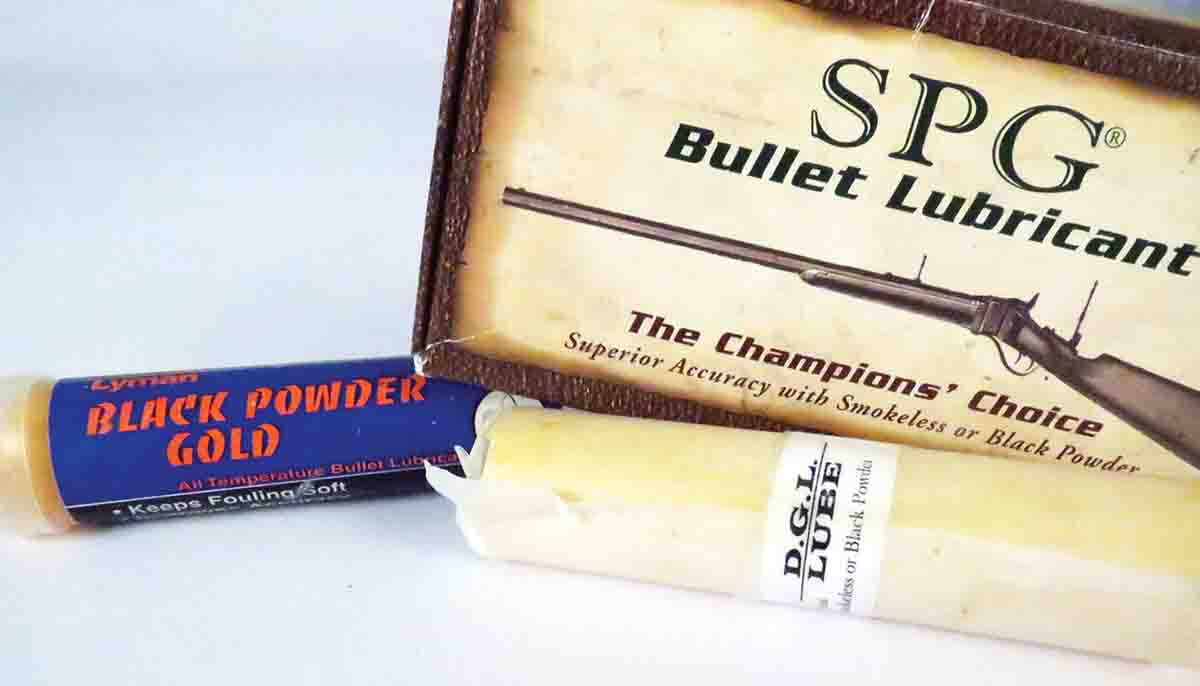

Back in 1986, I attended the second experimental BPCR Silhouette event put on by the NRA at the Whittington Center near Raton, New Mexico. My bullets were lubed with something given to me by Montanan Steven Paul Garbe. Using it, I did not clean my rifle’s barrel after every shot like other shooters were doing. Several people asked how I managed that and I showed them the grease ring at my rifle’s muzzle. That got the ball rolling and SPG Lube, now based in Missouri, is still very popular among BPCR shooters. Another black-powder specific lube making a name for itself is DGL. It was developed by an Idaho silhouette shooter named Fred Kase, and early in 2020, became the property of Johnny and Amber Spratling, also of Idaho. They are a very popular husband and wife silhouette shooting team. After they sent me a few sticks of DGL, I gave it a first try with my Lone Star rolling block .40-65 in August 2020, on the very difficult silhouette range at Butte, Montana. To say I was happy with its performance is an understatement, because after 22 years of trying on that range, I finally made a score of 30 hits on 40 targets. From the large reloading tool companies, to the best of my knowledge, only Lyman markets a black-powder specific lubricant. Named Black Powder Gold, it’s worked well for me also.

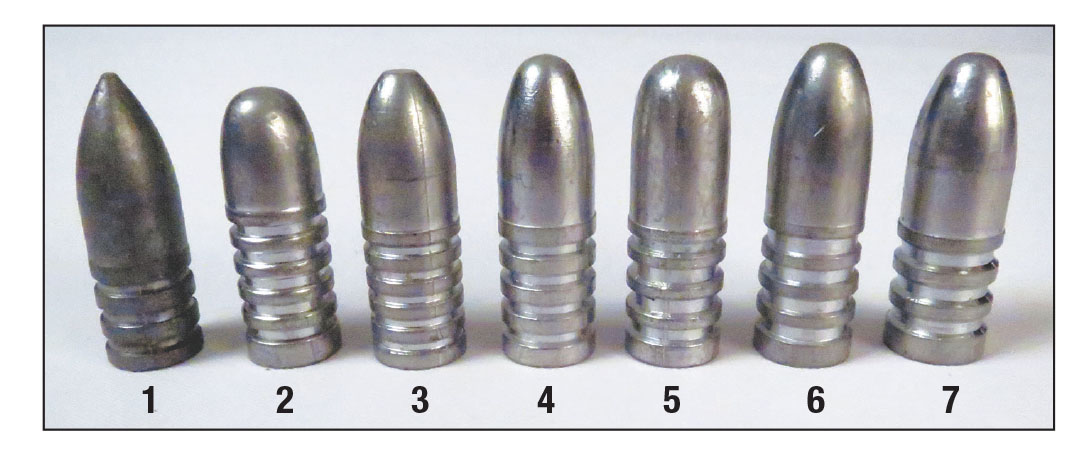

Considerable shooter experimentation has gone into developing finely accurate black-powder bullets for long-range shooting. Mostly because of the nose shapes, they carry a plethora of names: Government, Creedmoor, Postell, Money, Nasa, Schmittzer, Snover, Turkey Killer, etc. All have lube grooves except paper patch-types, which are another story entirely. I’ve shot bullets with three, four and even five grooves. I have off-the-shelf and custom moulds for many of the above mentioned designs. I’ve come to rely on Steve Brooks’ 425-grain pointed for my .40-65s and his 560-grain Creedmoor for my .45-70s.

Experience has led me to prefer heavier bullets than considered normal for the cartridge. For example, back in the late 1800s, 500-grain bullets were considered a heavy .45-70 (.45 Gov’t) bullet, but my pick mentioned above outweighs it by 60 grains. In most .40-caliber cartridges of the 1870s, 370-grain bullets were the heaviest available. My .40-65 bullet weighs 425 grains. The farthest I can shoot on my home range is 300 yards, and those bullets have been benchrest test-fired numerous times in five, 10- and even 12-shot groups at that distance. In calm conditions they will group in 1.5 MOA.

BPCR shooters are a gabby bunch. Entire dinner conversations often concern bullet details more often than their rifles. One thing garnered from being a part of such talk is that most of them dip their bullets from electric lead furnaces instead of using bottom pour pots. Why? The answer is bullet-to-bullet consistency. The theory is that molten alloy under pressure from the 20 or so pounds of alloy above splashes or swirls when hitting the mould cavity. Also, as the casting session increases in length the amount of alloy in the pot diminishes and changes the pressure by which molten alloy drops into the mould cavity.

Conversely, a dipper delivers the same amount of alloy for each pour no matter what level of alloy remains in the pot. Is this theory valid? Of course, I cannot prove how bottom pour pots cause bullet variation, but after weighing literally a couple tons of bullets, I’m convinced dipper pots rule. Here’s another question. What is acceptable variation? I’ve heard it bandied about that a plus/minus of one grain is okay. Personally, I think that’s a lot considering that variation in bullets probably comes from interior defects, which would affect flight characteristics over long range.

There are two other prevailing bullet mould factors I’ve determined from all the hundreds of conversations I’ve had with shooters these past 35 years. One is that the vast majority of BPCR competitors use single-cavity moulds. Again, consistency is the reason, and most people also use iron moulds. (However, I want to stress that a Spokane fellow named Dave Yount has beaten me in many BPCR Silhouette matches using an aluminum, double-cavity mould for his .45-caliber bullets.) Lyman, RCBS and Redding/SAECO all market BPCR-specific bullets. I’ve even had a hand in advising each company about what they need. Furthermore, there are several custom mould makers, such as Hoch, Steve Brooks and Buffalo Arms. The BPCR moulds produced by those three shops are top-notch. There are likely more custom makers out there, but I’ve owned and used many moulds from these three.

Lastly, there’s the question of “size or don’t size” BPCR bullets. That’s a tough one. Some great shooters do size in regular size/lube machines. Others say no; if your mould is good enough, it’s not necessary. Those folks pan-lube their bullets. I’ve tried both but ended up sitting right on the fence. For the sake of convenience, I’ve settled on the lube/sizing machine method but, using a die perhaps .001 inch over bullet diameter.

Here’s what I ask for in BPCR target bullets. A full diameter body of from .60 inch to .80 inch in length with four or five grease grooves at least .010 inch in width. Its body diameter should be at least the same as the rifle’s groove diameter to .001 inch over, and its nose should be no more than .002 inch under the barrel’s lands diameter. Any .45 bullets I use would be 530 grains and up, and my .40s would be 400 grains and up. As for nose shape, I don’t care. Just about every type mentioned or shown in this article can deliver fine accuracy.

.jpg)