Cartridge Board

.38 Special Target Wadcutter

column By: Gil Sengel | October, 21

Results of this first shooting weren’t impressive, but many folks became interested. Within a year, guns, cartridges and shooting techniques improved to the point that the target was moved out to 50 yards. Matches became 50- and 100-shot affairs. Handgun accuracy suddenly became important.

The history of the .38 Special was covered in this column in Handloader No. 185 (February-March 1997). There was not, however, enough space there to do more than just mention the existence of specialized target loads. That oversight will be corrected here, because the work that went into the .38 Special target load makes it an entirely separate and unique cartridge from self-defense rounds.

Target shooting with revolvers became so popular that the range was cut to 25 yards and moved indoors. Now shooting could be done year-round. If there was not space for 25-yard targets, the distance was shortened to 30 to 60 feet. Called “gallery shooting,” guns used were all manner of .22 rimfire rifles and revolvers, along with centerfire revolvers. Because of bullet stopping concerns indoors, the centerfires could not use full-power ammunition. This led to a line of .38 Special target cartridges known as “gallery loads.”

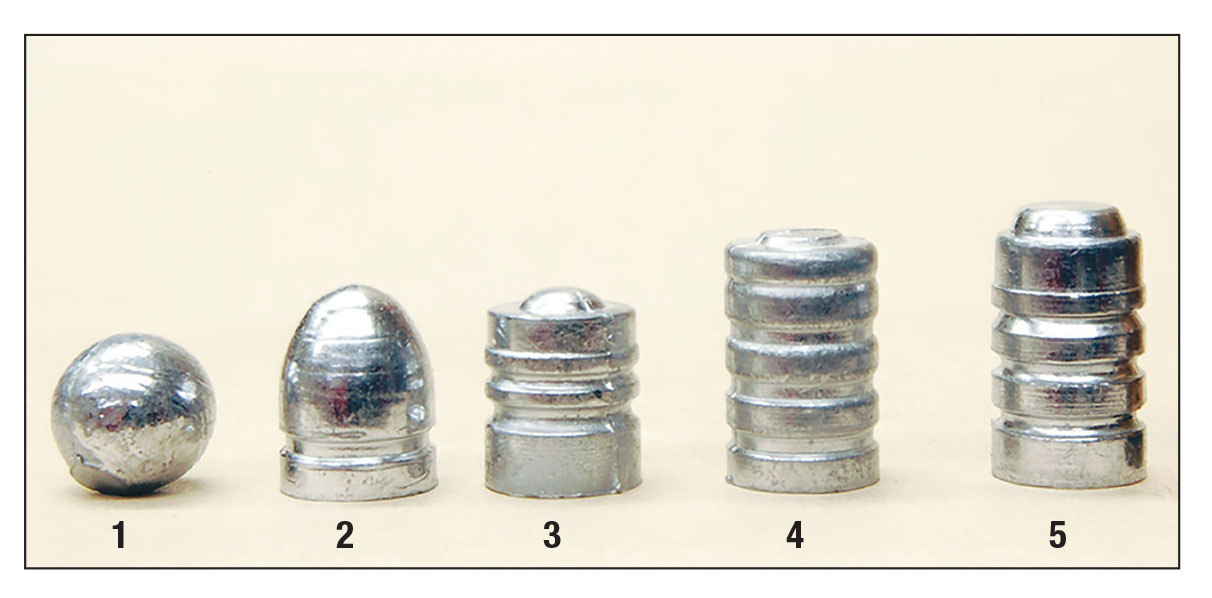

For the shortest distance, most ammunition companies offered a 70-grain roundball seated over a pinch of powder. For 25 yards, Winchester sold what it called a midrange load consisting of a short, blunt, 104-grain bullet. Both were listed using smokeless powder, but could also be had with black powder. Then in 1911, Winchester offered what it called a midrange Sharp Corner bullet of 123 grains weight. The nose was bore (not groove) diameter, flat, and protruded about .200 inch from the case mouth. A narrow band just forward of the case mouth was groove diameter to center the round in the chamber throat. Today, we call this bullet a wadcutter. Muzzle velocity was just over 600 feet per second (fps). The impetus for the design was that the low velocity made necessary by gallery shooting caused difficulty in scoring targets. Bullets did not make a hole or even remove any paper, but only linear tearing when passing through the target. Round balls were the worst offenders. The new bullet punched out a clean, full-diameter hole that was easy to score.

The adoption of the Colt Model 1911 .45 ACP by the army led many pistol shooters to become infatuated with it. It could not yet compete with big-bore revolvers at 50 yards, so 25-yard courses of timed and rapid-fire were adopted to favor it. Others allowed only the military gun.

Competitors now began asking for a .38 autoloader. It would seem simple to just chamber the M1911 for the already existing .38 Colt Auto and develop a target load. The chronicles indicate this was done, but the project failed for various mechanical reasons. A few dedicated individuals, however, continued to work on the problem.

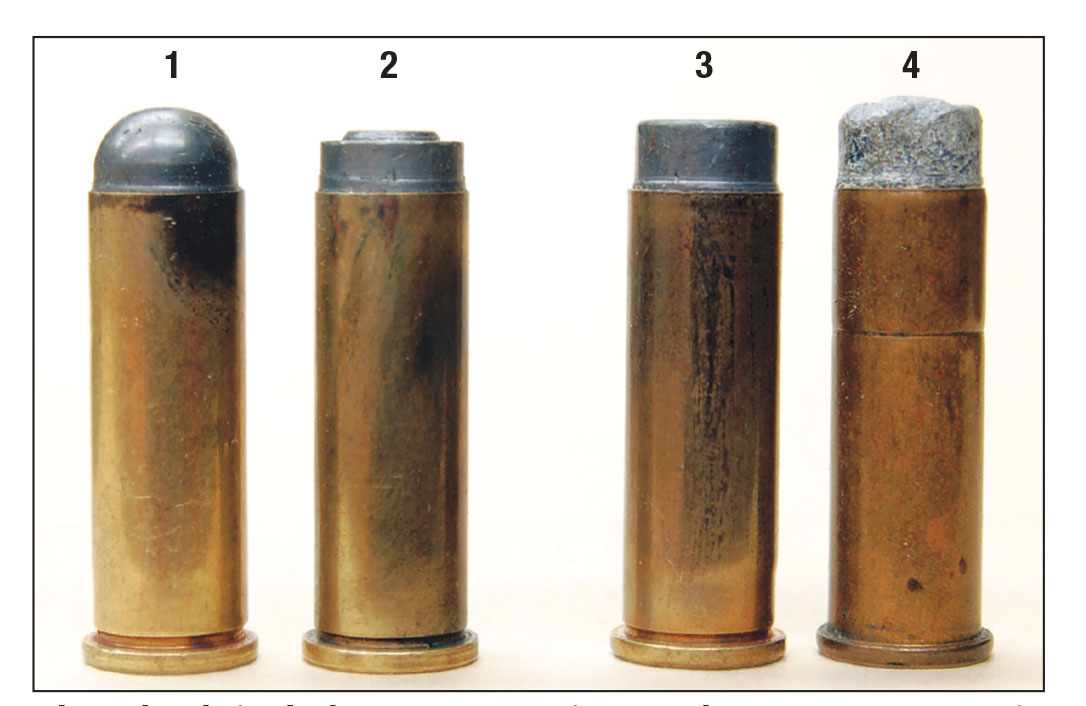

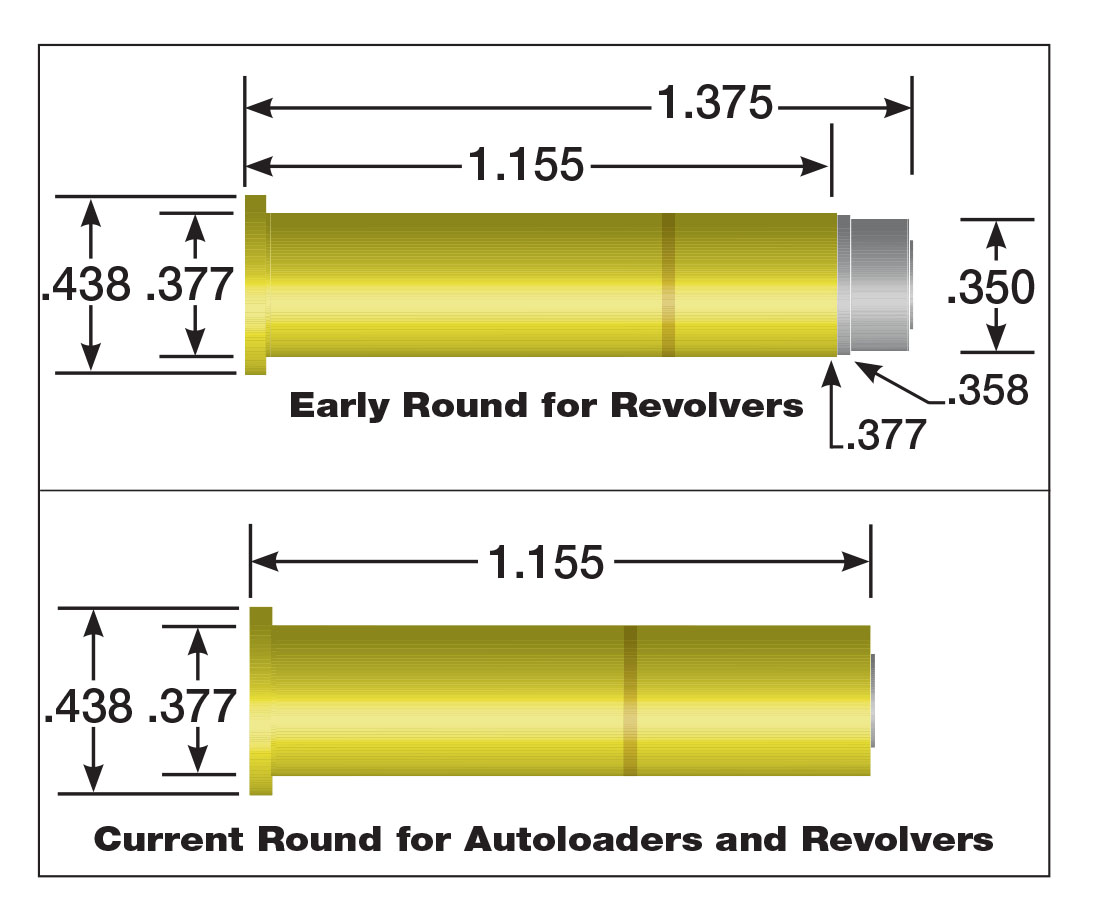

By the 1950s, the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit (AMU) at Fort Benning had modified the M1911 to fire a semi-rimmed .38 Special case using a wadcutter bullet seated flush with the case mouth. Remington and Western made special runs of the cartridge. Meanwhile, others had used an unaltered .38 Special case. This round won out over the AMU design.

In 1962, Colt announced its National Match .38 Special Gold Cup M1911. S&W followed in 1963 with its .38 Special M52 auto. Both fired only cartridges using 148-grain, flush-seated, hollowbase wadcutters traveling 770 fps at the muzzle. This new round became the .38 Special factory target cartridge.

The only drawback was handloading. All competitors use handloads for practice, but seating and retaining the flush-seated wadcutter is a challenge. Some suggest trimming cases back .025 inch, seating to factory overall length and lightly crimping. Careful case trimming is required, as is keeping the short cases segregated. A few “experts” counseled not to handload at all! Good heavens, it’s not that difficult.

Development of the 148-grain, flush-seated, .38 Special target cartridge has continued. Today, there are seven examples listed in the U.S., including Fiocchi, Magtech, Remington, Winchester, Black Hills, Sellier & Bellot and Federal. Muzzle velocities are all 700 fps, give or take a few feet. They are also shot in both autoloaders and revolvers.

Thus the .38 Special target wadcutter soldiers on in either flush-seated form or seated out conventionally in handloads for use in revolvers only. Despite being very accurate in most guns, and cutting clean holes in target paper and animal hide, most handgunners today have never heard of it. That’s too bad because it allows the fun of shooting a centerfire gun without the noise and recoil of modern defense loads.

.jpg)