Colt's Single Ation Army

Fifty Years of Shooting Iconic Revolvers

feature By: Mike Venturino | August, 18

That was the summer between my first and second years of college when I was hustling freight on a dock for $1.60 an hour. Buying that .45 pretty much ate up two weeks’ take-home pay. It was fall before reloading equipment was purchased. The reason for the delay was that with a few weeks between my job ending and school beginning, I used my ready cash for a camping trip to Montana. Best money I ever spent!

sizing die and happily reloaded hundreds of rounds for both handguns with that single set of dies and one mould.

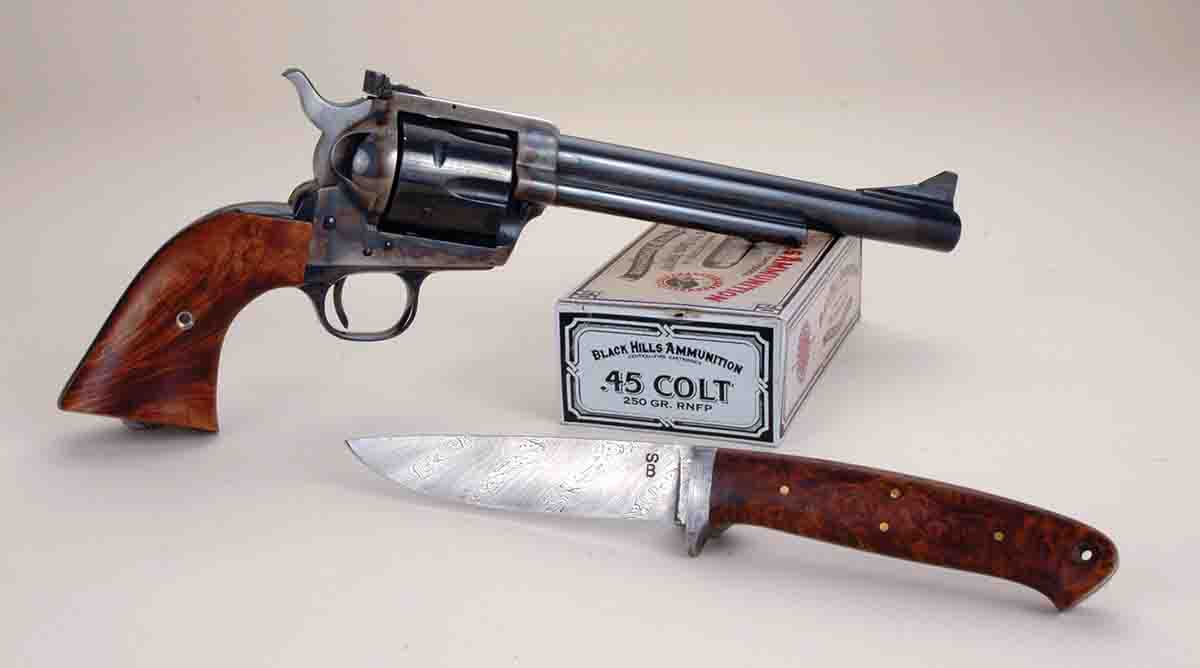

Now 50 years later my most recent Colt SAA cost 22 times more than that first one! It is also a .45, but from the 3rd Generation of production. It has a 7.5-inch barrel and is based on the misnamed “black powder frame.” To me that made it worth a premium. According to its serial number, it left the factory in 2008 and is every bit a nicely crafted revolver as was that first .45. Today I have a plethora of suitable moulds and reloading tools for it.

Since that fateful day in 1968, according to my handwritten notes, I have owned another 83 SAAs if a single .45 New Frontier is included. These have included all three generations, with some each of full-blued, full nickel-plated and blue/case-

colored frame finishes. The barrel lengths have included 3, 3.5, 4, 4.75, 5.5, 7.5 and 12 inches. The earliest SAA I have owned was made in the 1880s, but the exact year of manufacture escapes my memory. It was a .38-40, but interestingly there was a tiny “.44 CF” stamped on the trigger guard’s left side, meaning it

At this point, let’s nail down this matter of “generations.” According to Colt, there have been three. Running continuously from 1873 to 1941 was the 1st Generation. Serial numbers started at 1 and stopped at 357859. The 2nd Generation started in 1956 at serial number 0001SA and ran to somewhere between 73000SA and 74000SA. Almost all parts are interchangeable between 1st and 2nd Generation SAAs. After a hiatus of two years for retooling and some engineering changes, the 3rd Generation was introduced. Serial numbers took off at 80000SA and ran to 99999SA in 1978. Then the SA became a prefix, with numbers jumping to SA01001. For some reason, 1,000 numbers were skipped. In 1993 number SA99999 was made, so Colt’s move was to make “S” the prefix and “A” the suffix. Serial numbers started at S02001A. (Note this time a skip of 2,000 numbers.) Several 3rd Generation parts are not interchangeable with earlier production runs. The most recent 3rd Generation samples of which I am aware have been in the S75000A range.

A well-known fact is that Colt chambered the SAA for about 36 cartridges in the 1st Generation. Only five were truly significant: .45 Colt, .44 WCF/.44-40, .38 WCF/.38-40, .32 WCF/.32-20 and .41 Colt, in order of total numbers made. There were four choices in the 2nd Generation: .45 Colt, .44 Special, .357 Magnum and .38 Special. In the 3rd Generation, all of the above cartridges were offered at one time or the other, except .41 Colt. Over the last half century, I have handloaded all of the rounds mentioned in this paragraph to the collective tune of many tens of thousands.

When Smith & Wesson introduced its .357 Magnum in 1935, the company stayed with the same .357-inch barrel groove diameter used for .38 Special. I thought that surely Colt would also have moved from .354 inch to .357 inch for such a high-pressure round. It did not. My Colt SAA .357 Magnum’s barrel made in 1969 slugs exactly .354 inch.

If you are not confused yet, try this one on: When Smith & Wesson introduced the .44 Russian in 1872, followed by the .44 Smith & Wesson Special in 2008, specifications for barrel groove diameter was .4295 inch. Colt did not follow suit. It used .426/.427 inch minimum/maximum for the .44 Russian, .44 Special and .44 WCF/.44-40 barrel groove diameters. Something written many times is that 1st Generation Colt .45 SAAs (1873 to 1941) used .454-inch barrel groove diameters, but when the SAA was reintroduced in 1956, that specification was changed to .451 inch. I have a Colt factory specification sheet dated 1922 that lists .45 Colt, .45 Auto and .455 Colt barrels as measuring .451 to .452 inch across their grooves. That specification sheet also gives all calibers from .22 to .45 a rifling depth of .035 inch, making bore diameters .007 inch smaller than barrel groove diameters.

For the purposes of this article, I sat down with plug gauges and measured every chamber mouth on two dozen Colt SAAs of all generations. Here are some bare bone facts: Of nine .45s, chamber mouths varied from .453 to .456 inch. Of six .44-40s, the measurements ran from .428 to .431 inch. Five .44 Specials varied from .430 to .433 inch. Sometimes all six chambers were the same per revolver, and sometimes they varied within the range mentioned above. Now get this: All five of my .38-40s, ranging in age from 1904 to 2004, had uniform .400-inch chamber mouths.

Reloading manuals can give readers far more detail than I can in a couple thousand words. My only caveat about manuals is this: Be sure to refer to one that lists lead-alloy bullets. Of the cartridges listed above, only .32-20 and .357 Magnum might benefit from jacketed bullets because they can give velocities upwards of 1,200 fps from modern SAAs. Lead-alloy bullets will suffice for all other calibers.

Here are details on how I handload for more than two dozen SAAs after more than 50 years of experience. Admittedly, I no longer have a .32-20, .38 Special or .41 Colt, but if a bargain-priced sample was waved under my nose, I would not be averse to owning another in those calibers.

First consider bullet alloys, keeping in mind sometimes mismatching chamber mouth and barrel groove diameter variations. My experiences are that when using harder alloy blends of, say, a BHN of 15 and higher, bullets close to chamber mouths in diameter will give best results. For example, in .45 Colts that would be .454-inch bullets, even if the barrel groove diameter is .451 inch.

With that said, seldom do I use such hard bullets anymore in handloads for Colt SAAs. At sedate velocities of about 700 to 900 fps, soft alloys actually result in less lead fouling

What about bullet shape? I’ve told this story before but will repeat it here. The first time I went ground squirrel shooting with Colt SAAs, a .45 and a .38 Special accompanied me. The .45 Colt used conical – essentially roundnose – bullets. The .38 was used to shoot semiwadcutters. Several times the little varmints were hit well with .45s only to still run to their holes. Those hit solidly with .38 SWCs just sort of collapsed. There’s a lesson here: Roundnose bullets are fine for steel targets and plinking, but a wide flatnose is better for game. Because I also shoot many SAAs alongside leverguns, roundnose/flatpoint

Upon beginning loading for .45 Colt in 1968, Unique was the most commonly recommended smokeless propellant. It was almost always used, even after .44-40, .38-40 and .41 Colts were added to my list. Extensive machine rest testing over the years indicated that Red Dot often provided exceptional accuracy in .45 Colt, but about 6.8 grains of W-231 gave the best results in all three of those cartridges when the goal was duplicating factory ballistics. For the smaller bore sizes, Bullseye, Titegroup and W-231 all sufficed.

Then IMR’s Trail Boss arrived on the scene. It is simply a volume-filling yet fast-burning smokeless propellant. In large cases, usually those originally intended for black powder – as most Colt SAA big bores were – Trail Boss fills that volume well. It is virtually impossible to double charge a case with it, because it will overflow. I switched to it (nearly exclusively) for Colt SAA cartridges down to the size of .38 Special. (I’ve never tried it in the .41 Colt.) It gives perfectly adequate accuracy and velocity for casual shooting, and if my ears are to be trusted, its muzzle blast seems milder.

On the other end of the spectrum, if a handloader really wants Colt SAAs to buck and roar, use black powder. It will cause a .45 Colt’s muzzle to point skyward with every trigger pull and provide as much velocity as can safely be achieved in big bore, SAA-size cylinders. Until fouling gets heavy, black powder can also deliver decent groups.

My book Shooting Sixguns of the Old West is available from Wolfe Publishing: (800) 899-7810, wolfeoutdoorsports.com, and it covers black-powder handloading in detail.

Please note that in the accompanying extensive load table I’ve only included bullet designs cast by myself. These are bullets over which I had complete control in preparation, diameter sizing and lubricating. Results with commercially cast bullets can vary greatly from my findings.