From The Hip

Sixgun Tips For Cast And Jacketed Bullets

column By: Brian Pearce | December, 17

There was a time when all sixgun bullets were constructed more or less of pure lead. The velocities associated with early sixgun cartridges such as the .45 Colt, .44 Special and .38 Special, as well as short rifle cartridges chambered in revolvers, including the .44-40, .38-40 and .32-20 Winchester, were generally under 1,000 fps. At these velocities, lead bullets worked very well and still do. Granted, all of the above cartridges started life as black-powder numbers and needed the relatively soft lead (around 5 to 6 BHN) so the base of the bullet would obturate and form a gas seal at lower pressures. This was essential to prevent fouling and obtain accuracy.

Handgun ammunition began to change with the development of autoloading pistol cartridges, such as the .30 and 9mm Lugers and .45 ACP, etc., the bullets for which received some form of jacket to help prevent fouling in the various pistol actions and bores. Sixgun loads changed little, however, until the advent of .38-44 High Velocity loads that appeared in 1930 (a high-pressure version of the .38 Special cartridge designed for use in heavy “44”-frame guns, that propelled a 158-grain bullet to around 1,100 fps from most revolvers). While factory loads contained lead bullets, select loads, such as the “metal piercing” versions, were first fitted with a special steel tip and alloyed lead bullet. These were soon changed to feature a steel jacket and eventually a copper jacket. Although the production costs were increased, ammunition manufacturers discovered that jacketed bullets were especially easy to load on their automated machinery and eliminated barrel leading.

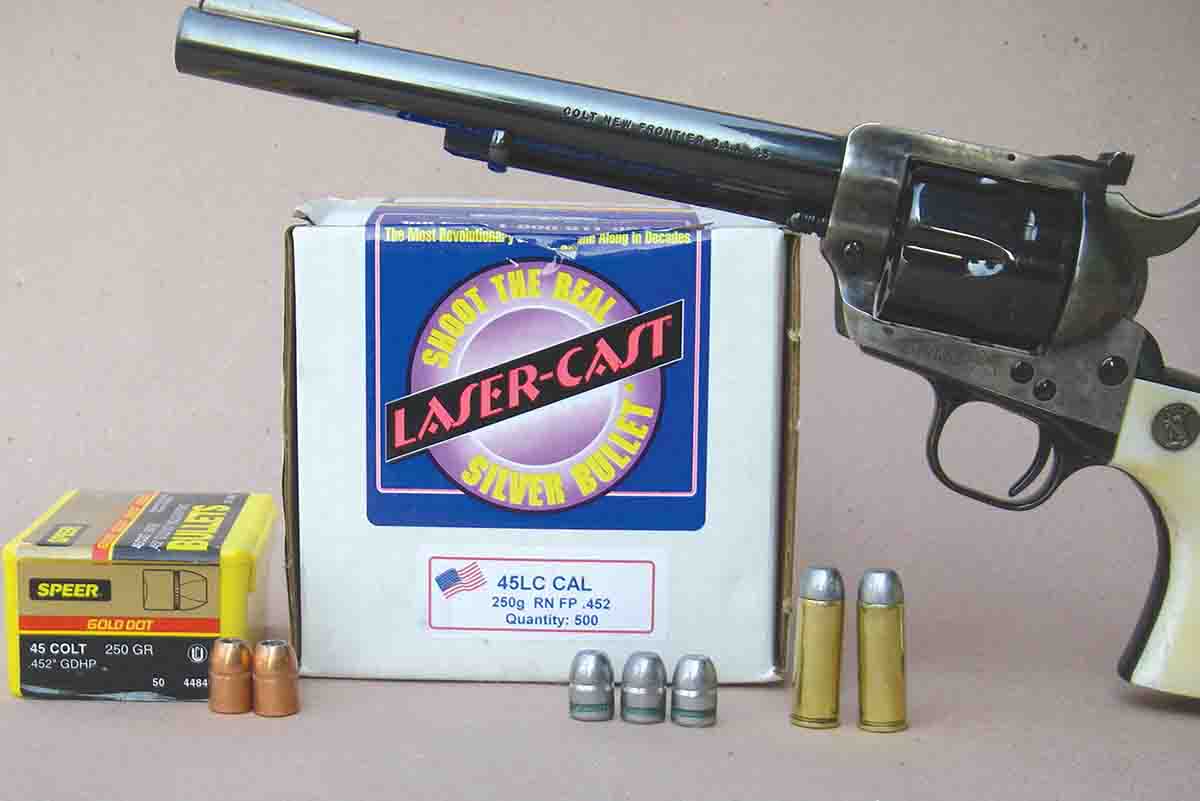

Of much greater concern is the possibility of sticking a jacketed bullet in the bore when fired from a low-pressure cartridge. This should be of special concern to handloaders, as there is a considerable amount of published data for .38 and .44 Specials, .45 Colt and others that will stick bullets in the bore or come very close. In short, the pressure energy is insufficient to reliably push bullets from the barrel, which is compounded when a revolver has a tight bore or a large or excessive barrel-cylinder gap (greater than .012 inch), which further reduces velocities. Usually the same powder charge can be used in conjunction with a cast bullet of the same weight that will reliably exit the barrel. The reason is simple: Jacketed bullets require much greater force to be pushed down a barrel, whereas comparatively soft lead and hard cast bullets will slide down the barrel with much less force. When lubricated with high-quality lube, their resistance is reduced even more. As a result, cast bullets generally reach notably higher velocities when used with the same powder charge and are far less prone to sticking in a bore. For these reasons, I generally favor cast (or lead) bullets in standard-pressure cartridges, or when magnum sixgun cartridges are loaded down to similar velocities and pressures.

Jacketed revolver bullets are generally manufactured with a crimp cannelure that, when seated and crimped accordingly, are within the overall cartridge lengths established by the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI). In other words, they will function in all guns, including bolt-action and lever-action rifles that sometimes will not function with longer cartridges. There are exceptions to this, such as the Hornady .44- and .45-caliber 300-grain XTP bullets that feature dual crimp cannelures and offer handloaders the option to seat bullets farther out to increase powder capacity.

Many cast bullet designs are intended to increase sixgun performance and seat to overall lengths that exceed SAAMI specifications. Common examples include Elmer Keith designs loaded in the .357, .41 and .44 Magnums, .45 Colt and others, as well as LBT Long Flat Nose (LFN) bullets and similar designs. In most revolvers, but not all of them, this is not a problem, as their cylinder lengths will readily accept longer cartridges. There are several advantages in seating to longer overall lengths, usually including better bullet-to-bore alignment, closer bullet proximity to the rifling to help reduce skidding, and increased powder capacity. The latter feature lowers pressure, but most performance-minded shooters prefer to increase the powder charge until maximum pressures are reached, which naturally increases velocities.

Cast and lead bullets are sometimes criticized for causing barrel leading, which can be a legitimate concern; however, much of this unjust reputation stems from magnum factory loads produced during the 1960s and 1970s. Factories loaded .357 and .44 Magnum rounds with swaged lead, plain base bullets that had minimal lubricant and were pushed to 1,400 fps or faster. I vividly recall shooting these loads in sixguns that had sparkly, clean bores, but after firing just six rounds the barrels were so badly leaded that accuracy was horrible, and the rifling was completely coated with lead.

If handloaders use the correct bullet design that is properly alloyed, leading can be very minimal or nonexistent, even when fired at magnum velocities. When a load is working properly, several thousand rounds can be

A few guidelines that might help achieve top accuracy and prevent barrel leading when using lead and cast bullets include limiting velocities to around 800 or 900 fps when loading comparatively soft, swaged lead bullets from Hornady and Speer, which can be very accurate. When using commercial hard cast, bevel-base bullets (typically with a BHN of 15 to 22), velocities should be held to 1,000 fps or less. To help prevent fusion and bullet tilting in the throat, they usually shoot best when fired in guns with throat diameters that are close to the diameter of the bullet. For velocities of 1,000 to 1,100 fps or slower, plain-base bullets cast with a BHN of 10 and sized close to the same diameter as the revolver’s throat will perform well. When plain-base bullets, such as the Keith design, are shot at magnum velocities of 1,200 to 1,400 fps, it is preferable to cast them with a BHN of 14 but not over 16, and use a high-quality, soft lube. Some barrels may still be prone to leading, which may be the result of a rough or improperly cut forcing cone, a rough bore or imperfect chamber-to-bore alignment. In these instances, switching to a gas checked bullet can be an excellent solution.

While cast bullets can be carefully alloyed and hollow-pointed to achieve perfect expansion, they

are mostly known for offering deep penetration. Notable designs featuring a flat point (meplat) are extremely effective for hunting big game.

Jacketed bullets from companies such as Hornady, Sierra, Nosler and Speer can offer outstanding accuracy and performance and are often very forgiving to imperfect sixguns. For example, years ago I had a Smith & Wesson Model 29-5 .44 Magnum with a 6-inch barrel, nearly perfect chambering, chamber and barrel alignment and a properly angled and smooth forcing cone. The bore, however, showed slight chatter (uneven waves) along about the last inch and a half. It wouldn’t shoot any cast bullet worth a darn but would commonly group Hornady and Nosler 240-grain jacketed HP bullets into around 2 inches at 50 yards.

If loading jacketed bullets in standard-pressure cartridges, due to their bore resistance, I generally choose lighter than “standard” bullet weights. In the .38 Special, for example, I drop from 158-grain lead bullets to 125- to not over 135-grain jacketed bullets. In the .44 Special, the standard 246-grain lead RN bullet is replaced with 200- to 220-grain jacketed examples, and the traditional 250-grain lead bullet in the .45 Colt is changed to a 200- to 230-grain jacketed bullet. These changes reduce the amount of bullet-bearing surface and allow velocity to be increased, reducing the possibility of sticking a bul-

let in the bore. Increased velocity also allows reliable expansion, which generally cannot be accomplished with jacketed bullets of standard weight, at least if pressures are kept within industry guidelines.

While jacketed bullets are often appreciated for reliable accuracy, they also provide predictable expansion at correct velocities. Over several decades, I have shot many mule deer and whitetail deer with Hornady XTP-HP and Speer Gold Dot HP bullets (now known as Deep Curl) at velocities from 1,300 to 1,400 fps that time after time have given picture-perfect expansion and predictable terminal performance. I have also had excellent results with jacketed sixgun bullets offered by Winchester, Sierra, Nosler and others.