The .348 Winchester

Loads for a Winchester Model 71

feature By: R.H. VanDenburg, Jr. | December, 17

When it came to the cartridge, Winchester continued with an odd size. Bullet diameter was .348 inch; the .33 Winchester had a bullet diameter of .333 inch. The case decided upon was the .50-110 Winchester, which also served as host to the .50-105, .50-100 and .50-110 High Velocity, depending on powder charge and bullet weight. The .50-110, introduced in 1887, had a case length of 2.400 inches, a rim diameter of .610 inch and a base diameter in front of the rim of .553 inch. The new cartridge was simply shortened to 2.255 inches and necked down to accommodate a .348-inch bullet diameter with the other dimensions remaining the same. Body length became 1.650 inches, case body and shoulder together became 1.804 inches with a remaining neck length of .451 inch. Shoulder angle was 19 degrees, 4 minutes. These dimensions are from current sources such as the Hornady Handbook of Cartridge Reloading, 10th Edition. Some earlier sources listed the same cartridge overall length but with a neck in excess of .5 inch.

The rifle and cartridge were introduced in January 1936, with the .348 Winchester cartridge loaded with 150- and 200-grain bullets. Various reports of factory-original muzzle velocities for the 150- grain bullet range from 2,890 to 2,920 fps. Muzzle velocities for the 200-grain bullet have been reported from 2,520 to 2,535 fps.

In The Rifle in America, Phil Sharpe notes that he became aware of the new cartridge early on in its development during a visit to the Winchester factory. He was able to test fire the experimental cartridge as well. At the time, cases were headstamped “.34 Winchester,” and Sharpe kept a sample for his collection. Considering the two-digit designation old fashioned, Sharpe suggested the company go with three-digit nomenclature reflecting the groove diameter of the barrel, hence, the .348

It is interesting to note that at the time all this was going on at the Winchester plant, the company was developing a new bolt-action rifle to replace the Model 54 – the venerable Model 70, which was also introduced in January 1936. This explains how the Model 71 got its name. It was not named after its year of introduction like other Winchester lever actions; it was simply the next number available.

The Model 71 Winchester was only chambered in the .348 Winchester cartridge, and the cartridge was only chambered in the Model 71, with a couple of exceptions. The original load offerings of 150- and 200-grain bullets were met with a demand for a heavier, 250-grain bullet. In time, Winchester complied. The 150- and 200-grain bullets were introduced as part of the company’s Super Speed lineup. The 250-grain load was first offered with a Silvertip bullet. Eventually all three bullet weights were available as Silvertips. Other companies, such as Remington and Peters, produced .348 Winchester ammunition, with Peters offering a 210-grain Belted bullet.

In 1987 Browning began selling a Japanese-made replica of the Model 71, also in .348 Winchester. Parts were not interchangeable with the original, but the rifles were well received. Both rifle and carbine models were offered in standard and Deluxe editions. The rifles appeared in the 1988 Gun Digest with the notation that production would be limited to 3,000 rifles and 3,000 carbines. By 1991, Gun Digest no longer listed the model, suggesting the run ended in 1990. Despite its relatively short run and limited production numbers, the Model 71 and Browning look-alikes are held in high esteem in Alaska. Its lighter weight and handling characteristics have made it a favorite with those who hunt and fish where contact with big bears is likely.

Even though ammunition options are restricted to a 200-grain bullet, the demand for new .348 Winchester component cases is high. It would appear few cases have been the basis for so many wildcat cartridges ranging from the .348 Improved through the .375, .416, .458 and even the .50 calibers. The most well known is likely the .450 Alaskan.

My involvement in all this began a couple years ago when a good friend walked into his local gun emporium, spied a Model 71 resting in a corner and decided quite rightly that life would be better if he returned home with it.

Calling to celebrate the new purchase, he casually informed me he had for some years 100 new, unprimed .348 Winchester cases. He ordered loading dies and bullets, and I researched loading data. Upon arriving at his place with said data and a few powders, we set about loading cases for his “new” rifle. It was the standard version, sans checkering, sling swivels and pistol grip cap. The rear sight was a Williams peep. The levergun was in quite good shape; according to the serial number, it was manufactured in 1949. At his local gun club range, we hit a snag. Lowering the rear sight until the cross piece barely cleared the gun’s vertical locking lugs still left 200-grain bullets impacting more than a foot high at 100 yards. Clearly, the previous owner had shot it little, if at all, as such performance would be unacceptable under any condition.

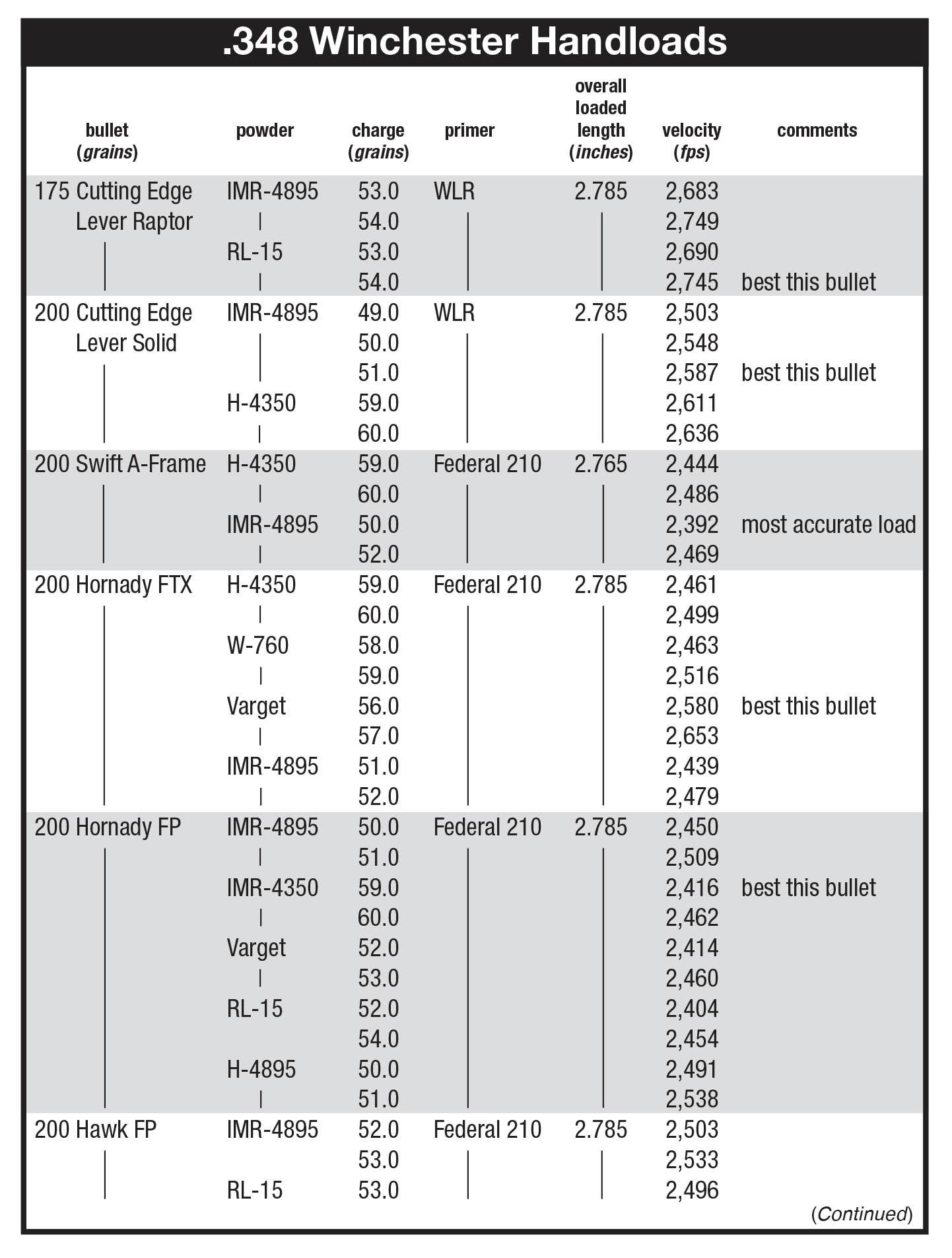

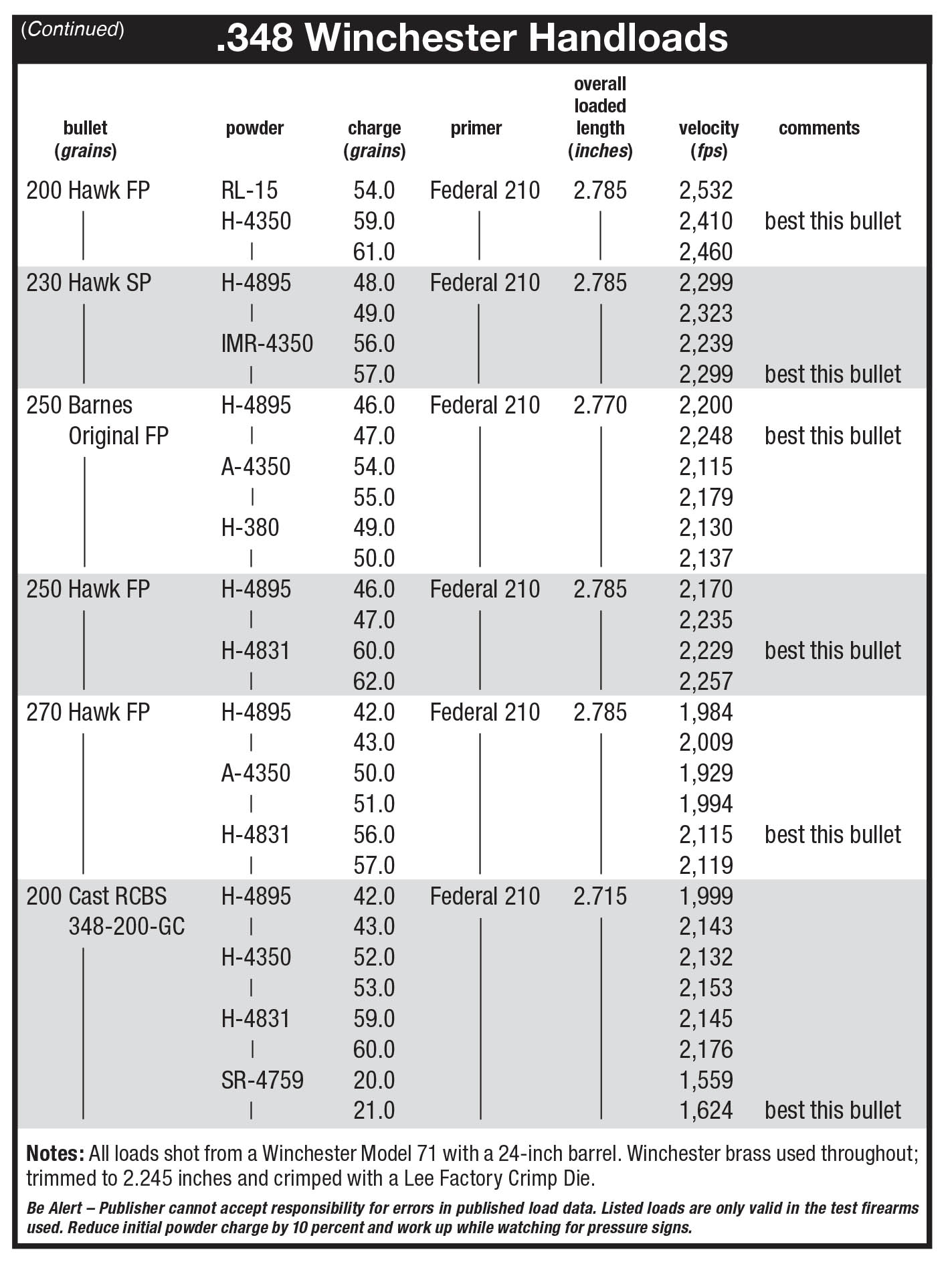

Powder selection began with IMR-4895. Especially with 200- grain bullets, it seemed about ideal, but since most load data developed with it was fairly old, there were now several powders with similar burning rates that needed to be explored. Eventually 11 were chosen.

Bullet selection turned out to be a surprise. I ended up with 10 jacketed bullets ranging in weight from 175 to 270 grains, plus one 200-grain bullet cast from an RCBS mould. Most were flatpoints, befitting the lever-action, tubular magazine design. There were two exceptions: a Hornady 200-grain FlexTip (FTX) bullet with its polymer tip, and a Hawk 230-grain SP developed, I’m told, because Ruger once chambered its No. 1 rifle in .348 Winchester. Cutting Edge provided two bullets, a 175-grain Lever Raptor and a 200-grain Lever Solid. Both are homogenous brass. Swift contributed a 200-grain A-Frame. Hornady makes two .348 bullets, the aforementioned FTX and a 200-grain InterLock FP. Barnes lists 220- and 250-grain bullets in its Original lead core series, but I was only able to obtain the 250-grain bullet. Hawk Bullets provided four: a 200-grain FP, 230-grain SP, 250-grain FP and a 270-grain FP. The company makes a 250-grain SP, but I did not have a large enough sample to conduct any tests (the Hawk 165-grain FP was not available at the time of my testing). And last, a cast RCBS 348-200-GC 200-grain bullet.

Eleven bullets and powders, with multiple powder charges of each, promised to be too daunting a task of little or no value, so decisions had to be made. IMR-4895, the long-time favorite, was the fastest-burning powder selected and performed extremely well across the board, but other slower powders, all the way to H-4831, had their moments. The powders I would rate best are IMR-4895 for most uses up through 200-grain bullets, along with IMR-4350, H-4350, Reloder 15 and Varget. For bullet weights above 200 grains, H-4831 produced the smallest groups and extreme velocity spreads. Also performing well in this group were IMR-4350 and IMR-4895. For cast bullets, several powders performed well, but the best in terms of extreme spreads and group sizes was SR-4759. As this powder was recently discontinued, I would fall back on either IMR-4895 or H-4895.

Another snag was discovered during the handloading and shooting process. Lever actions tend to lock up at the rear of the bolt, thereby allowing for a certain amount of flexing upon firing. This in turn leads to case stretching. If a handloader is not careful in the sizing operation, case separation is inevitable. That said, keeping cases trimmed to 2.245 inches, setting the shoulder back no more than is absolutely necessary to smoothly close the action and not seeking the maximum muzzle velocity not only solved the problem, but also ensured a reasonable case life of five or more loadings.

For example, it is easy to find load data for the popular 200-grain bullets showing a muzzle velocity in excess of 2,500 fps. Reducing this to 2,400 fps was all it took to minimize case stretching in the borrowed rifle. This backing off from maximum loads would hardly be noticed in the woods at peep sight ranges and frequently produced tighter extreme spreads and smaller groups. To be fair, some of these high-velocity loads shot very well, especially with Cutting Edge bullets, but the price was too high in case life, at least for me.

Crimping when loading cartridges to be used in lever actions is a necessity. A Lee Factory Crimp Die accomplished this chore well on bullets with and without cannelures.

Narrowing down bullet choice was difficult and best left to the individual shooter and his specific needs. That said, at least one load with each bullet performed very well. For game such as pronghorn and whitetail, I would not select bullets heavier than 200 grains. For heavier game, strongly constructed, 200-grain bullets and those of greater weight are a better choice, especially in close timber. Among the 200-grain choices, I became particularly enamored of the more lightly constructed Hornady 200-grain FP and the more strongly constructed Swift A-Frame. For heavier bullets, in this particular rifle, the Hawk 250-grain FP really stood out.

All bullets shot to the same windage. Vertical stringing at 100 yards was due to velocity variations. A 270-grain Hawk bullet might barely reach 2,000 fps, whereas a top-loaded Cutting Edge 175-grain Lever Raptor could slide over the screens at 2,800 fps. The most pleasant to shoot and most generally useful were 200-grain bullets at 2,400 fps or so. The best 100-yard, three-shot groups hovered around 2 inches – certainly adequate given the sights and likely uses.

Looking back, the Model 71 and its cartridge may well be anachronisms, relics of an earlier age. But for those of us who admire the handiness of the action type and the slower and quieter pace of hunting in the woods, there will always be a place for a good lever action.