Non-Toxic Shotshells

A Toxic Experience?

feature By: Terry Wieland | December, 24

With the deadline in mind, I had about four weeks, so I set about assembling the wherewithal. First, of course, I needed some bismuth shot and given the state of the reloading supply chain, that proved to be neither easy nor cheap. Finally, I cornered a couple of pounds of No. 5 and No. 7. However, No. 6 bismuth, which is probably the most useful for upland birds, was nowhere to be found. That should have told me something.

Little did I know, that was just the beginning. In a rush of intuitive genius (okay, just common sense) I had them throw in two of their manuals: The Bismuth Manual, 7th Edition and the newest The 16-Gauge Manual, 12th Edition. I had an earlier 16-gauge book, but I wanted the latest edition, given the constant changes in components and load data. When they arrived, I read them cover to cover, and only then did I realize what I’d gotten myself into.

We’ll deal with the gauge itself only briefly, because this article is about non-toxic generally and bismuth in particular.

Ever since it was left off the list of gauges for competitive skeet, the 16 gauge has been the orphan in the crowd. There is nothing in the way of light target loads, not much in the way of vital components like reloadable hulls or a selection of wads, and load data itself is rather scanty. Hulls are the particular bugbear. American hulls are mostly older technology, intended for hunting and, the ammunition companies being what they are, attempt to make the 16 a ballistic match of the 12. It can’t be done, but they keep trying.

Fortunately for us all, Europeans love the 16 gauge and have for eons, and both Fiocchi and Cheddite offer excellent new hulls. Rather than scrounge around and try to figure out which salvaged hull was which, I bought several hundred primed Fiocchi hulls and went from there. This served a dual purpose, since a great deal of the load data in The Bismuth Manual calls for Fiocchi or Cheddite hulls.

Bismuth is very different than lead, not just in toxicity, but in its physical characteristics. Bismuth is an element (symbol: Bi) whose most familiar use is probably as an ingredient in Pepto Bismol, which gives you an idea of how benign it is. It’s less dense than lead, but heavier than the steel commonly used in non-toxic shot, and it appealed to shooters initially because it’s softer than steel and hence friendlier to barrels and chokes.

Since pure bismuth pellets have a tendency to crumble rather than compress like lead, it’s alloyed with tin to make it more malleable.

To combat all of these traits, manufacturers offer bismuth pellets not only alloyed with, but coated with, tin.

Great? Sort of. Bismuth is already more expensive than premium lead (roughly $14/pound vs. $2/pound while tin-plated bismuth ups that to $18/pound). At that point, the pellets going into a one-ounce load are costing more than a buck per shotshell.

There are other non-toxic possibilities. The original, steel (iron), actually costs the same or even less than lead, while “polished” steel costs more and “zinc-plated” steel is the most expensive at around $2.50/pound. Regardless, steel retains all the negative characteristics that caused us to look for others in the first place – less dense, meaning less penetration per pellet, yet very hard, resulting in possible damage to barrels and chokes.

Ballistic Products sells the wonderfully named “BPX Devastator Tin-Plated Tungsten” for about $31/pound, while the equally evocative “SpheroTungsten Super Max-18” is almost $45/pound. Consider that a pound contains 16 one-ounce loads, and you are looking at a cost of almost $3 a shell – just for the pellets. Shoot a round of trap with this stuff, and it will cost $100 in ammunition alone – always assuming the trap club would let you use it.

As you can see, non-toxic shot is a world of trade-offs, with your choice depending on whether you value ballistic performance over economy, or worry more about cost than you do potential damage to your gun.

So, back to bismuth, which in light of the foregoing looks both economical and benign to your treasured old gun, as well as likely to be lethal to anything it strikes. It is also a good example of the particular problems presented by non-toxics.

There is one immediate and immutable caution: Load data must be followed to the letter, with no substitutions of any kind, this includes primers, hulls, shot cups – nothing.

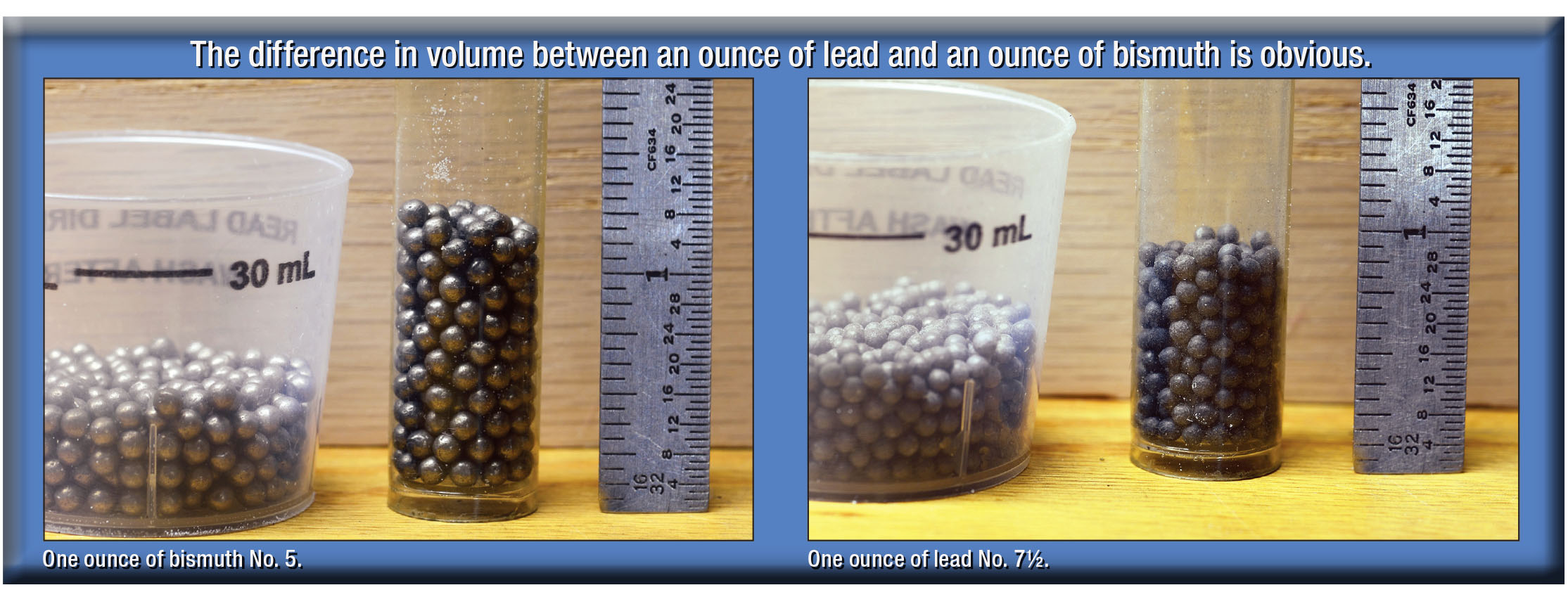

In order to create a shotshell that is both lethal and functions reliably in your shotgun, the components must fit perfectly and be tightly packed to allow a firm crimp. Because an ounce of bismuth occupies more space than an ounce of lead, we use different shot cups and may or may not need filler wads to occupy excess space.

Because of its physical qualities, bismuth shot needs to be treated differently both in the loading machine and in the shell itself. In the loading machine, uncoated bismuth-tin alloy still tends to bunch together and clog, unlike lead that rolls around. As well, the tendency of pellets to crush and break, or get out of round, also contributes to such jamming.

I found that each time I dropped a charge of pellets, I needed to rap the loading tube a few times to jar loose any that were stuck and even that did not always work. Often, the pellets would shake loose as the ram was raised, spilling bismuth all over everything. Looking on the bright side, unleashed in this way, it does not bound and roll as far as lead.

When next I make a purchase, it will be for the tin-plated bismuth in an attempt to forestall this. It costs half as much again, but worth it for the amount I’d be using.

In the interests of all the components moving freely and fitting together, Ballistic Products recommends shaking the shot cups with Mica Wad Slick to reduce friction. They seat in the hull more easily and it also reduces friction in the bore. Presumably, the slicker interior walls on the cup contribute to the bismuth pellets seating themselves comfortably. I can’t attest to this, but I used it and everything went together just fine.

A small scoop full is added after the shot charge is dropped, and the case is gently tapped to distribute the buffer among the pellets. (The actual amount of buffer varies from load to load and gauge to gauge, but a set of Lee scoops solves every problem.) Having done this, an over-shot card is added to keep the buffer from leaking out. A final touch that is not required but strongly recommended is a dab of crimp sealant. This prevents the crimp creeping open and the pellets dribbling out and also seals the case against moisture.

There are other requirements if you are loading steel or tungsten, such as the use of Mylar or Teflon wraps to provide an additional barrier between the shot and the barrel walls, but these are not needed for bismuth. I mention them just to show how individual the requirements can vary for one type of non-toxic versus another, as well as to illustrate why a progressive press is not much help in such specialized, small-scale loading, which requires considerable hand labor.

One problem you will run into, especially if you load a variety of non-toxics, is measuring. Shot is measured by ounces in the load charts, but by volume in the loading machine. MEC machines have charge bars graduated to an ounce (or whatever amount) of lead shot, and trying to find one that works with an ounce of bismuth (greater volume) or tungsten (less volume) will drive you mad. Ballistic Products offers an adjustable bar that solves all the problems. You only need one, so at $100, compared to $25 for individual bars, it’s a bargain.

Still related to volume, often you will need wads of different thicknesses to occupy any extra space and ensure the load fits snugly. After trying to figure out what was what, I just bought a bag of everything available for each gauge I was loading.

As for measuring the buffer, which is always needed with bismuth, I purchased a complete set of Lee scoops. Like the selection of wads and fillers, that way you always have the size you need right at hand.