Powder Coating Cast Bullets

The Benefits and Downsides of Coating Your Own

feature By: John Haviland | February, 18

Powder-coating material is essentially plastic that has been ground into a fine powder, with resins, color and other ingredients added to provide the desired coating film. Polyester powders are the most common. Heat is applied to melt the powder that cools as a hard film, enclosing the bullets.

Powder can be applied to bullets by several methods, from complicated to quick. Harbor Freight sells a powder coat gun for $70. An air compressor that provides 10 to 30 psi of air pressure is also required. The gun blows negatively charged powder onto positively charged bullets. This electrostatic attraction adheres powder to bullets. This method requires standing bullets upright with enough space between them to spray an even coat all around the bullets, but leaves the bullets’ bases uncoated. Standing up a bunch of slender rifle bullets requires nimble fingers.

Simply tumbling bullets and powder together in a container turned out the cheapest and easiest way to coat bullets evenly. Putting bullets and powder in a Ziploc bag, closing the bag to contain the powder dust and gently tumbling the bag coated bullets fairly well. The clear plastic allowed me to see when bullets where suitably covered, but the bags eventually split and leaked powder.

This adhesion of powder to bullets relies on electricity, just like the powder coating gun. The polyethylene surface of Ziploc bags and soft plastic tubs tends into attract electrons when brought into contact with other materials. In this case, the material is lead-alloy bullets that give up electrons when brought into contact with polyethylene.

Some handloaders who powder coat bullets attempt to increase static electricity by adding plastic Airsoft BBs or copper-coated BBs to powder. Others tumble bullets while wearing wool socks and dragging their feet across carpet.

Bullets must be clean for the powder to stick. Nothing is freer of contaminates than freshly cast bullets, or bullets stored in a sealed container.

Some advice I read suggested to shaking a container with powder and bullets like a paint-shaking machine. Some handloaders even place a container in a vibrating case tumbler. All that vigorous shaking did for me was knock the powder off bullets. Gently turning a container end over end from a few to five minutes evenly coated bullets.

Transferring powder-coated bullets onto a pan to heat the bullets and melt the powder is a delicate process. Some folks use tweezers to pick up each bullet and set it in a pan, which is time consuming. Wearing latex gloves and picking out bullets is slightly faster, but touching the bullets in any way removes some powder. I gently rolled the bullets into a strainer positioned over a pail and lightly jiggled the strainer to drain excess powder. From there the bullets were slowly rolled into a pan lined with nonstick aluminum foil. Whether the bullets are standing up or laying on their side does not affect how evenly the powder cures. A slight space between bullets prevents them from sticking together and eliminates rough spots from forming where they touched.

Powder coating is a fairly clean process. I wore a dust mask and latex gloves while handling the powder. After shaking bullets,

A toaster oven is the most common heat source for melting powder onto bullets. A toaster oven was purchased for $20 at a local store, with a coupon and a discount. The oven rack holds an 8.5-inch square pan with some room to spare. Suggestions for oven temperature settings and baking time vary. I’ve read everything from 400 degrees for 20 minutes to 300 degrees at half that time.

I set the oven at 350 degrees and kept an eye on the powder as it began to melt on a batch of .30-30 bullets. After 15 minutes the powder had melted and a shiny coat of paint appeared on the bullets, but some of the bullets looked weird – as in they had started to melt and flatten. It was finally determined that the melted bullets had been directly over the heating element. A flat pan placed over the heating element spread the heat more evenly.

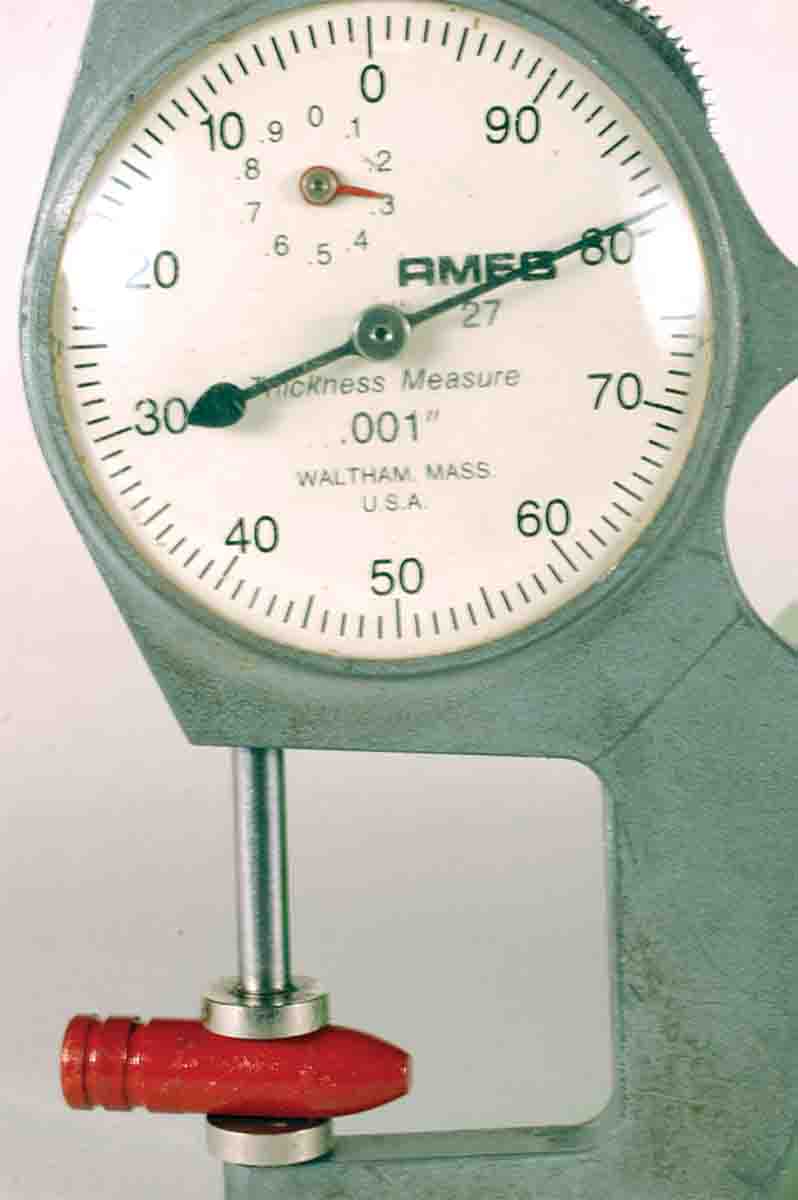

After some experimenting, an oven temperature of 350 degrees and a baking time of 15 minutes was settled on. Bullets that were laying on their side came out of the oven with an even coat. Some thin spots appeared here and there on some bullets coated once. The driving band diameter was .310 inch of as-cast RCBS 30-150-CM bullets. Diameter increased to .311 inch with one coat of powder.

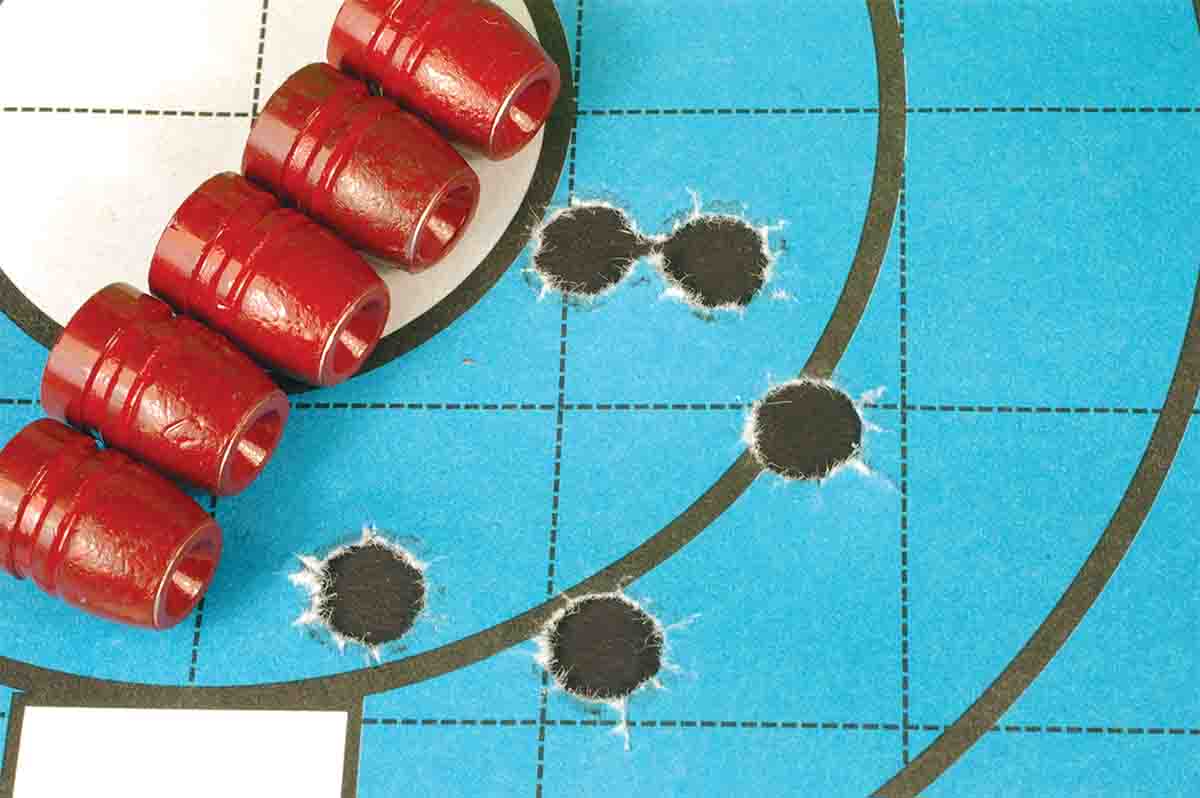

The finish on the bullets was slippery, and the bullets easily pushed in and out of a .309-inch sizer die. I shot 20-some of these bullets through a .30-30 at a velocity of 1,267 fps. A Lyman borescope showed a smear of red at the beginning of the rifling and a few streaks in the bore. They wiped out with a few brush strokes followed by two patches. There was no visible sign of leading.

The increased thickness made me leery of the coating; it might have filled crimp grooves enough to prevent applying a sufficient case mouth crimp on bullets to keep them in place during hard recoil. To put that worry to rest, I applied two coats of Harbor Freight Red Powder to bullets cast from an LBT 358-200-FN mould and crimped the bullets in .357 Magnum cases over 14.0 grains of Accurate No. 11FS powder. The bullets had a velocity of 1,163 fps fired from the 6-inch barrel of a Smith & Wesson Model 686 .357 Magnum revolver. Recoil was sharp. I left one cartridge unfired in the cylinder while firing ten rounds. Measuring the cartridge showed its length had remained unchanged.

Powder coating provides a hard surface on bullets. The paint does not crack or peel off when sizing bullets. Some of the NOE 453-210-RF bullets were shot from a .45 Auto into a stack of dry newspapers, and most of the coating remained on the shanks of the recovered bullets. After firing 20-some coated bullets through the .45, its bore was only slightly fouled, probably with primer residue.

Often when shooting plain cast bullets, you get a face full of smoke and a taste of lead when the wind blows in your face. Powder-coated bullets eliminated the smoke for sure, and perhaps some airborne lead.

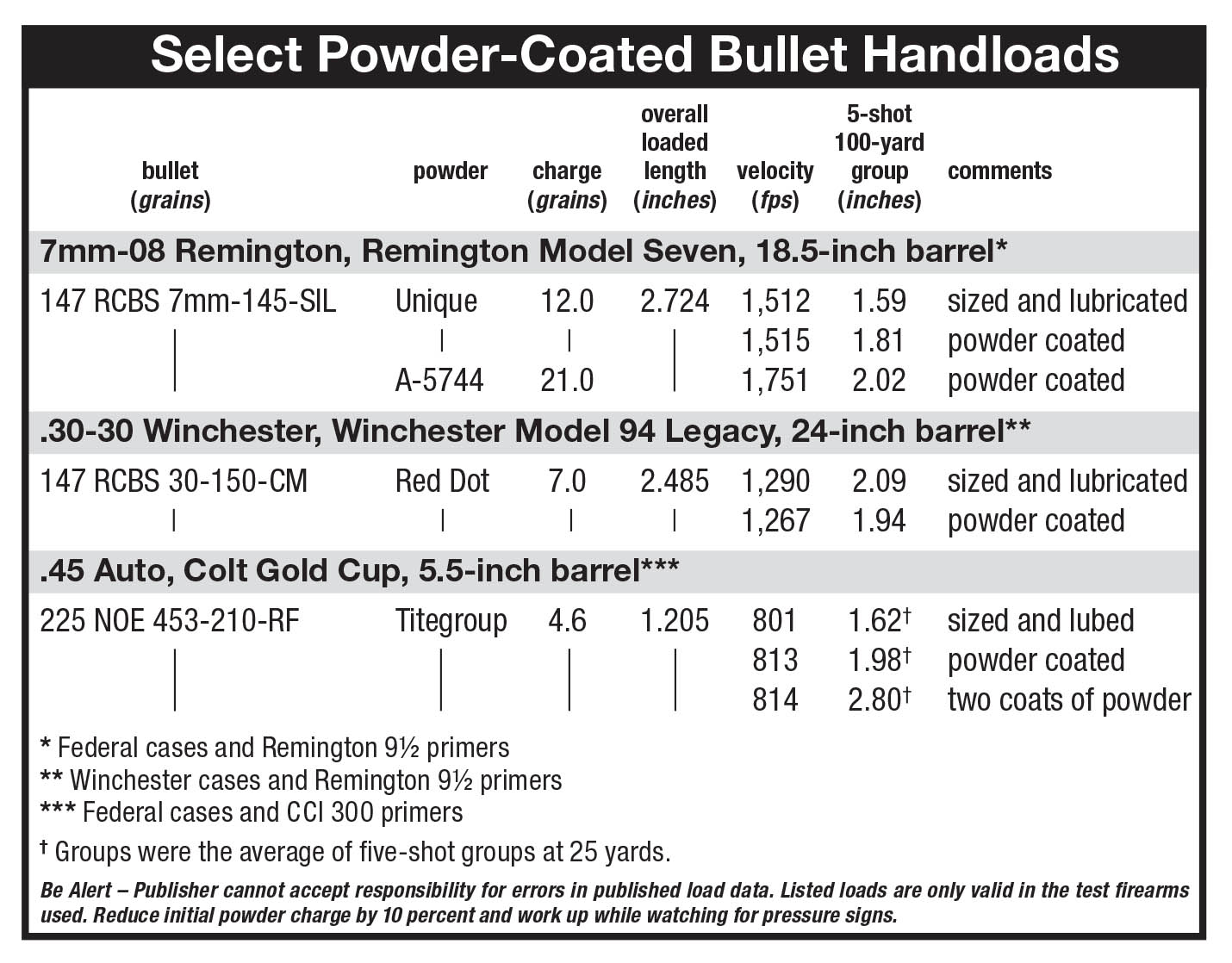

Powder coating does not strengthen a bullet’s lead alloy. Perhaps the coating does protect a bullet’s base somewhat from powder gas, but I’ve never seen where the plain base of cast bullets ever melted from the heat of powder gas. Pressure is what distorts a cast bullet and ruins accuracy. I shot RCBS 7mm-145-SIL bullets cast of wheel weights with gas checks through the worn bore of a Remington Model Seven 7mm-08. Fired with 12.0 grains of Unique, the velocity and size of five-shot groups was pretty much the same whether the bullets were lubed and sized or powder coated and sized. A borescope showed no streaks of lead in the bore. Increasing velocity to 1,751 fps using 21.0 grains of A-5744, groups widened a bit. After 10 shots, the borescope showed slight streaks of lead in a few spots in the bore. That was fairly well the bore’s condition after shooting sized and lubed bullets.

Powder coating bullets does require more time than the traditional method of running bullets through a sizer/lubricator press. Facing the daunting task of preparing a thousand .38 Special bullets, I would rather run the bullets through a sizer/lubricator press or choose bullets that drop from a mould the correct diameter, roll the bullets in a liquid lube and allow them to dry.

If the work of preparing cast bullets is pleasant and pleasurable for you, then the powder-coating process is a good investment of time and small expense of about $30. I’ll spend that time powder coating rifle bullets for hunting and target shooting so I don’t have to peer through a screen of smoke. Because they look so cool, I’ll even keep on hand some .30-30 and .45 Auto ammunition loaded with powder-coated bullets.