Turnbull Commander Heritage

Testing a New 1911 .45 ACP

feature By: Charles Petty | February, 18

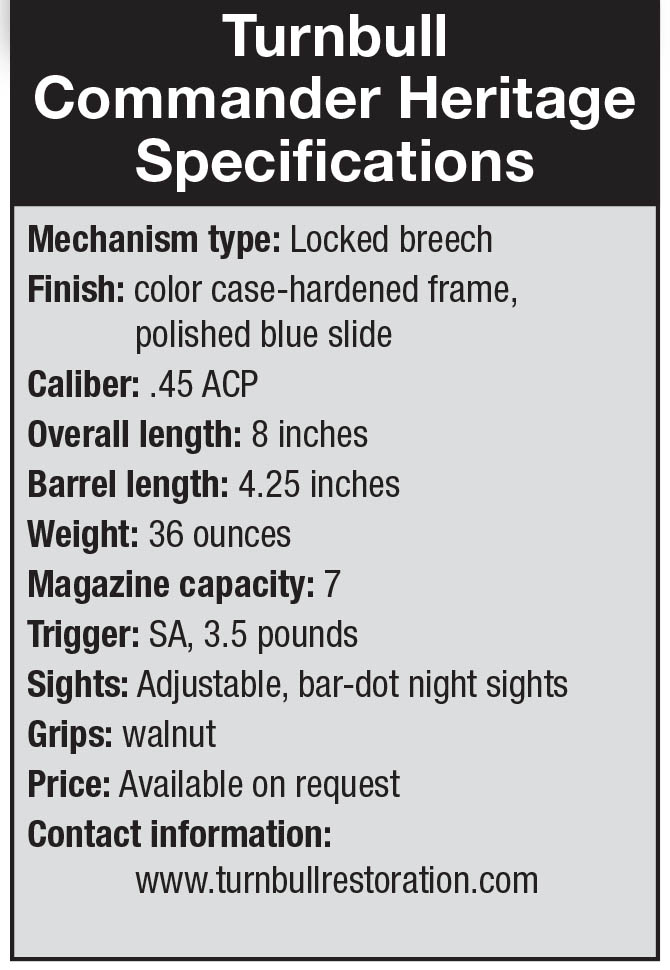

What struck me most was the simplicity of the Turnbull Commander Heritage. There are no frills, gee-gaws or eyewash that do nothing for the gun aside from driving up the cost. This is a prime example of understated elegance. There is a term, usually reserved for British Best sidelock doubles, that fits perfectly here: “Funeral Grade.” This term is applied to perfectly finished, black guns with little or no embellishment. A British-trained ’smith told me about these, saying they were very difficult to finish because of the long, flat surfaces.

Aside from the fact that the Commander Heritage is gorgeous, my gunsmith training took over for a thorough examination. There is no lateral or vertical movement of the slide. Pressing down on the chamber does not move the barrel. A bushing wrench is helpful but the barrel bushing moves easily enough. The barrel has a .5-inch segment that is 0.005 inch larger, which allows a better fit.

Turnbull’s barrel is a semi-drop-in style made to his specifications. Examination of the barrel shows evidence of light, precise fitting of the barrel hood with no gaps. For me the fitting of the bottom lugs was the most challenging part of an accuracy job, where one misguided swipe of the file could put you back at square one. With the Commander Heritage assembled it was impossible to feel any movement by pushing down on the barrel, and after shooting more than 500 rounds, there was light burnishing of the lugs.

Once upon a time the only source for 1911 parts was Colt, but largely due the growing popularity of practical shooting sports, a market and demand for parts was created and grew rapidly. Today it is virtually impossible to say who made what unless it is clearly marked. Detail stripping revealed an assortment of well-made, unmarked parts. The barrel mates nicely with the headspace cut in the slide.

When the pistol arrived, my first observation was an exceptional slide/frame fit with no wobble in any direction. The raw forging for the frame is purchased and finished by Turnbull, with special care in the case hardening process to avoid warping from the heat. The bar stock slide is finished in-house as well, and it bears the last four digits of the serial number. My suspicion is that

The front strap is checkered in two steps. First the pattern is laid out by machine but then finished entirely by hand. It has all the standard amenities such as checkering, a beavertail grip safety and extended thumb safety. The sights look like common tactical types, but they are fully adjustable Kensight night sights with a bar-dot pattern with two small bars on the rear and a single, larger insert on the front. Turnbull has reproduced the two-tone magazines – which were a signature of early Colt pistols – but without the toxic cyanide process of the originals.

Then I tried the trigger. I always complain about triggers . . . until now. It is a creepless, glass-rod breaking, consistent 3.5 pounds. Now that’s a trigger job. When I later had the time to detail strip the pistol, I saw why. When the sear and hammer pins are removed, they usually fall out, but these did not. They fit so well that it took a gentle punch to push them out. If the sear and hammer cannot wobble, that’s a good thing.

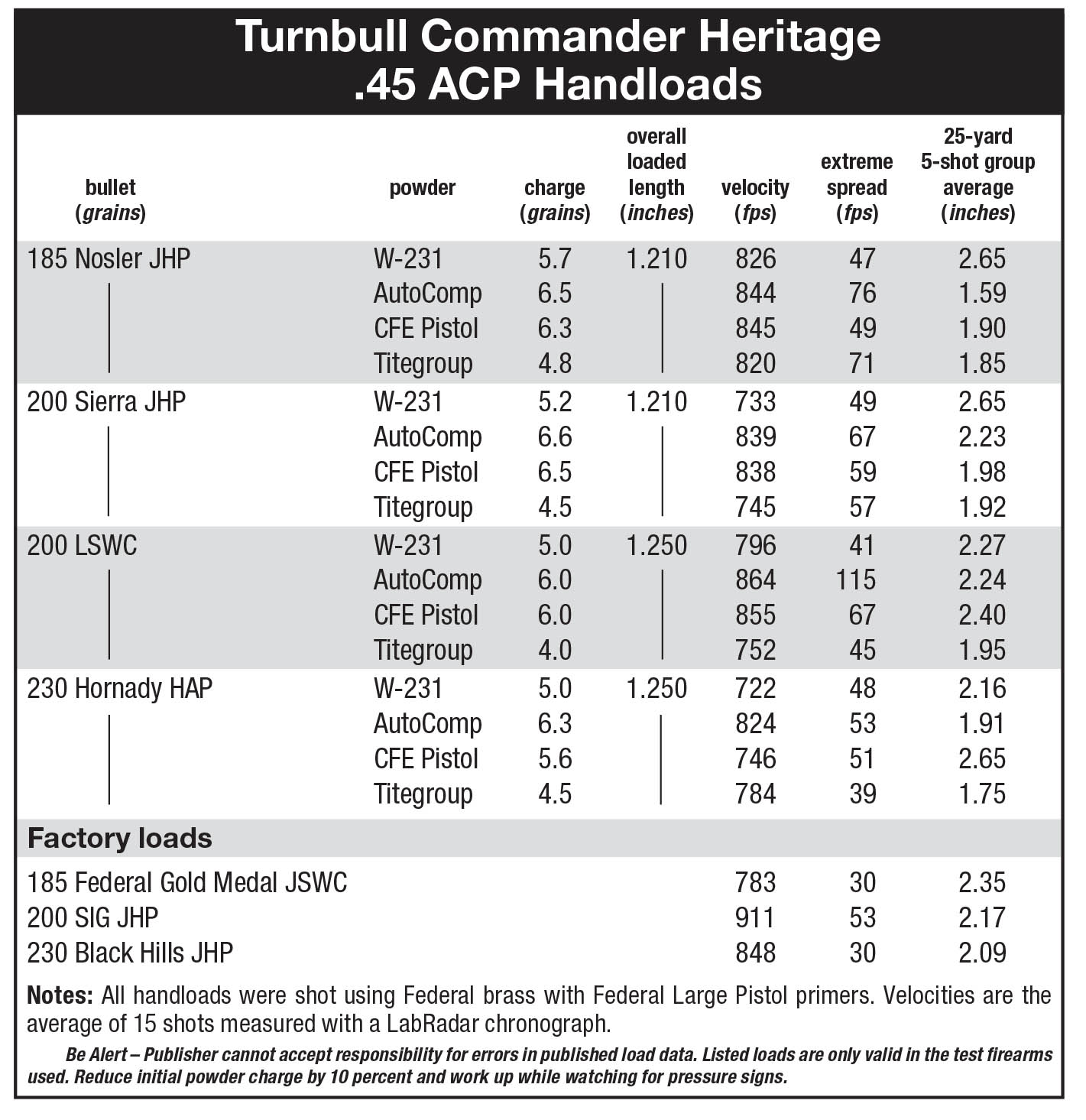

Any time a shooter embarks on testing a new gun he/she is faced with a nearly bottomless pit of decisions. That is especially true when handloads are intended to be used. Each element in the equation is a variable, and there simply is no way to study them all. So the first step was to eliminate less common bullet weights and styles. That left me with three weights: 185, 200 and 230 grains in jacketed hollowpoints, and one 200-grain lead semiwadcutter as a common plinking load. Brass and primers are also variables, but in most cases not big factors, with the exception of maximum loads, where it is prudent to follow the components used in the data source.

With any new pistol, testing begins with simple function shooting. There always seems to be a bunch of miscellaneous ammunition lying around, consisting of leftovers from previous efforts. They are an anonymous assortment of factory and handloads with bullets of every weight, type and shape. The Commander Heritage digested 50 of those without a hiccup.

Accuracy testing was next, following a pattern of 185-, 200- and 230-grain factory loads. Three, five-shot groups were fired at 25 yards from a benchrest, and velocities were recorded with a Lab-Radar chronograph.

Next came handloads. The loads used were chosen based on past experience with a group of powders that have performed well in the .45 ACP.

Whenever I look at accuracy data like this, my focus is finding the smallest and largest group, in this case 1.37 and 2.82 inches, respectively, but as I studied the table another thought appeared. Instead, I began to think about how similar they are. There are no shining stars or obviously awful loads. Within any group of five-shot strings, there could be well over an inch difference between the smallest and largest strings. It happens more often than most handloaders think. The bottom line here is that the accuracy of this Turnbull Commander Heritage is equal to, or better than, production guns that are not hard-fitted.