The 44-40 Turns 150

Beloved for Its Storied Past

feature By: Wayne van Zwoll | June, 23

These developments left a braided trail, their paths meeting and diverging, influenced by people and events unique to the times.

At the century’s midpoint, Sam Colt had blessed citizenry, cavalry and law officers with cap-and-ball revolvers. But hunters and infantry used muzzle-loading rifles. The idea of self-contained cartridges loaded from the breech had inspired a flurry of inventions.

Winchester promptly hawked it to the Union Army. Few rifles entered the Civil War, but they made an impression.

The Henry’s value lay in fast repeat shots, not in its ballistic acumen. At 1,025 feet per second (fps), the 216-grain bullet caused less damage than a patched ball from an 1858 muzzle-loading Springfield. But Winchester boldly puffed the Henry. As did this testimonial: “It is certain death at 800 yards, and probable at 1,000 …. [I’ll shoot my Henry] against any living man at 1,000 yards with any other gun….” This sunny report was later traced to Winchester’s St. Louis agent!

Sharps percussion rifles were also converted for metallic cartridges, including the popular 45-70. When Christian Sharps died young of tuberculosis, the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Co. soldiered on with burly single-shot rifles for proprietary Sharps cartridges: six 40s, three 44s, four 45s and three 50s. The “big 50” used 90 to 110 grains of powder in a 2½-inch case to send a 473-grain, paper-patched bullet at 1,320 fps. The frothier 3¼-inch, 50-140 Sharps was late to the party in 1880, when remnants of the great buffalo herds were widely spaced and not profitable to hunt. Notably, Sharps rifles were often abandoned by hostiles who had killed their owners. Unless cartridges were also at hand, such a rifle was useless. More highly valued: Springfields in the ubiquitous 45-70, and Winchesters in 44-40.

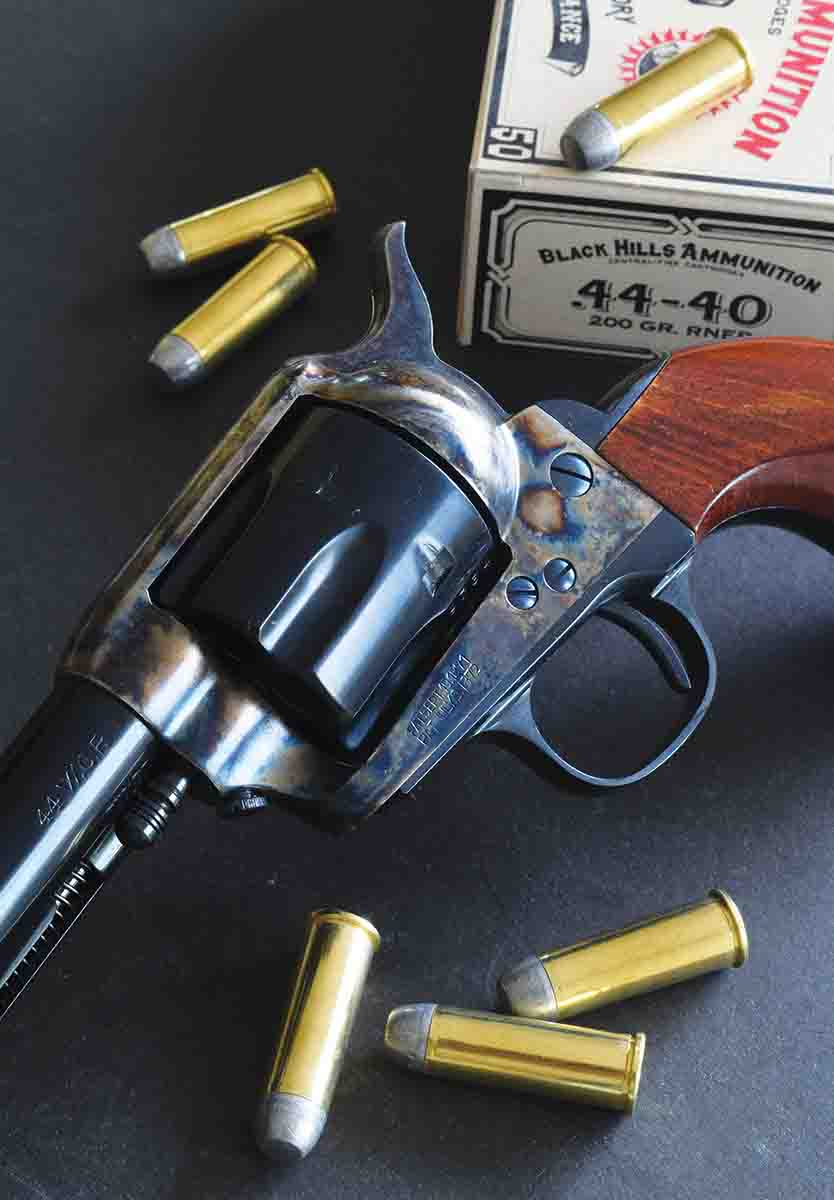

Brisk sales of Winchester’s 1873 spurred other gunmakers to offer rifles in 44-40. The 1883 Colt-Burgess lever-action chambered it, as did Colt’s slide-action 1885 Lightning. Sam Colt saw bright prospects for it in his 1873 Single Action Army revolver, introduced that year. From handguns, the 44-40’s 200-grain .427-inch bullet was no more effective than the 45 Colt’s slightly slower, 255-grain .452-inch bullet. But the 45 Colt was essentially absent in rifles. In 1878, Colt barreled its SAA to 44-40. Sales response was quick and gratifying – largely because the 44-40 absolved customers of buying different ammunition for rifles and revolvers.

The only fly in the ointment for the 1873 Colt and other solid-frame SAs was reloading. Clearing each chamber with the ejector rod was tedious. On horseback, it was also difficult – especially if bullets were flying. The top-break Smith & Wesson (S&W) Model 3 in 44 American and 44 Russian could dump a cylinder full of empties in 2 seconds. Poking hulls from an SAA took 26. Major George Schofield urged tweaking the S&W for cavalry. The army pointed out that while ammunition for a Schofield revolver would function in an SAA, the reverse was not true. Citing inevitable mix-ups in battle, it awarded contracts to Colt.

Winchester’s follow-up to the ‘73 was the similar but larger iron-framed 1876 for the long 45-75 W.C.F. cartridge. It lasted a decade. A better lever-action design appeared incidentally after a salesman traveling in the west brought to Winchester Vice President Thomas Bennett a secondhand rifle.

The stout, dropping-block, single shot would chamber the likes of the 45-70 and compete in a market then-owned by Sharps and Remington. Bennett traced the rifle to a Utah gun shop and bought a train ticket to Ogden. The shop was staffed by four brothers barely into their 20s. The eldest was John Moses Browning.

Son of a frontier gunsmith, Browning had fashioned his rifle without blueprints, using only basic tools. But Bennett was no fool. He recognized the value and wanted all rights to the single-shot rifle. Browning was no rube either. He pitched a price of $10,000 – a fortune in 1883! Bennett countered at $8,000, and on his return to New Haven, slated the rifle for production as Winchester’s Model 1885. During the next 17 years, John Browning sent 44 firearm designs to Winchester. Bennett bought them all. The lever-action Model 1886 rifle, with the vertically sliding lugs of his single shot, netted John $50,000.

Reportedly, Bennett offered Browning $10,000 for a short-action rifle like the ’86 “…if you finish it in three months.” John’s reply: “The price is $20,000. You’ll have it in 30 days, or it’s free.” The Model 1892 arrived early, a 44-40 clearly superior to the 1873. Chambered also in 25-20, 32-20 and 38-40, it sold to the walls at $18. Winchester would list it until 1941. With Models 53 and 65 variants (in 1924 and 1933), more than 1,034,000 Model 1892s would ship.

Marlin’s side-ejecting lever rifles competed ably with Winchester’s as black powder gave way to smokeless. The Marlin 1894 was barreled to the 44-40 and its three W.C.F. siblings, and produced until 1934. So too, Remington’s slide-action Model 14½, announced in 1913 in 38-40 and 44-40. By 1938, the 44-40 had fallen off the chambering rosters for all rifles built stateside.

I feed Black Hills Ammunition Cowboy Action cartridges to my 44-40s: a Cimarron Model P revolver and an original Winchester 53 rifle. This Black Hills Ammunition features excellent Starline brass and perfectly formed flatnose lead bullets. Accuracy is as good as I can tap. Mild pressures baby the guns and make shooting fun.

But not all 44-40 buffs are so easily pleased. Royal Stukey is one.

In another life as a cowboy riding for Wyoming’s Padlock Ranch, Royal told me his first 44-40 was a Navy Arms reproduction of the Henry rifle. “It shot accurately with factory-loaded 200-grain half-jacket bullets,” he said. “Remington and Winchester, mostly. That was when standard loads had some zip; they weren’t lead-bullet Cowboy loads loafing off at 700 fps. The bullets hit hard. From the side, they punched big holes through deer and pronghorns, killing cleanly without damaging much meat. A bullet quartering to the off-shoulder would break it and stay inside. Neat holes through coyotes were the rule. I saved pails of fired cases, but that thin brass didn’t fare well in my loading press. About one in five split. Fortunately, factory ammo was easy to find and not terribly expensive.”

Ah, those days! When I started shooting, about a decade before Royal, a box of 50 factory-loaded 44-40 softpoints cost about $8, same as 44 Magnum ammunition. Unprimed cases listed at $74 per thousand, bullets $60. Both affordable, if you saved your dimes. But handloading also required a press. My Herters, weighty enough to anchor a small destroyer, set me back $15. I thought hard before sending that check.

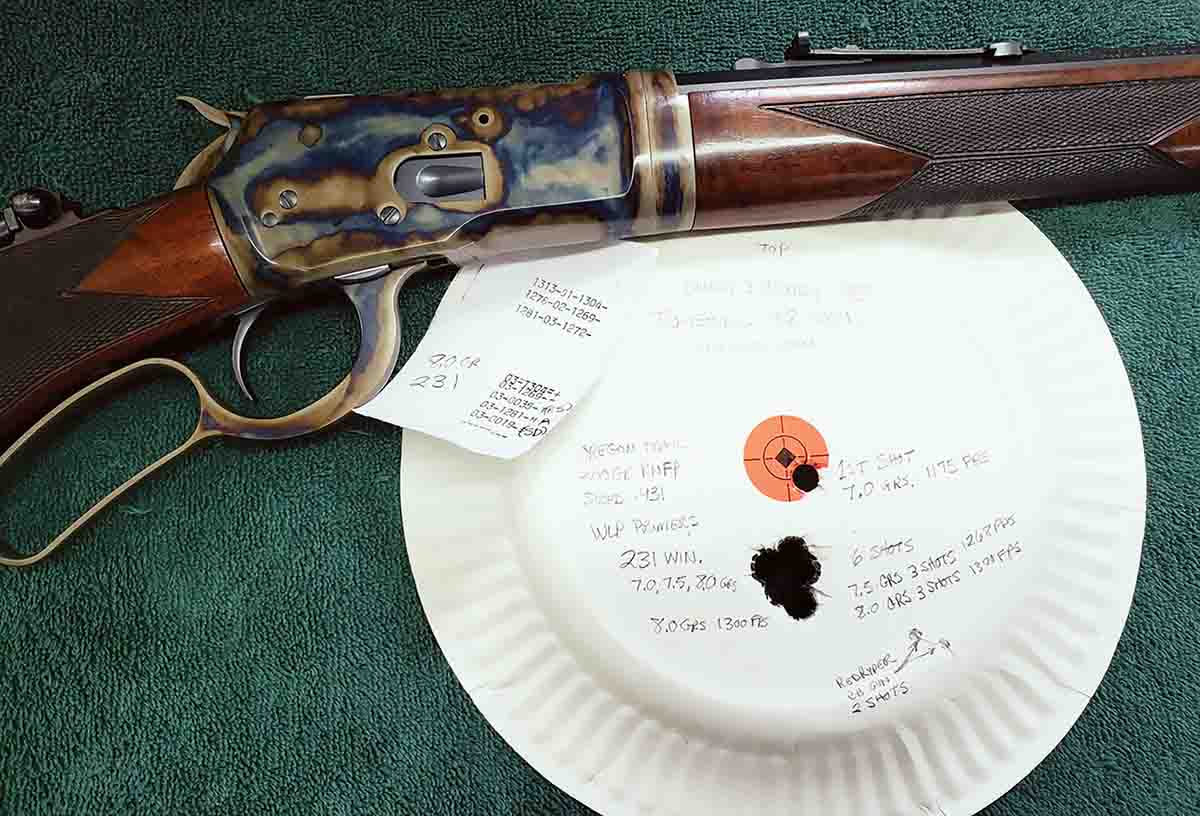

Like me, Royal now handloads for a variety of cartridges. Handloading is a natural extension of his real job – building superb shooting benches and adjustable rests for people obsessive about exceptional quality and wringing the most accuracy from their rifles. With his clients, he hugs carbon-fiber stocks to hurl skinny bullets through chassis-cradled, carbon-fiber barrels. But in unguarded moments, he confided to me that such rifles have the personality of gateposts.

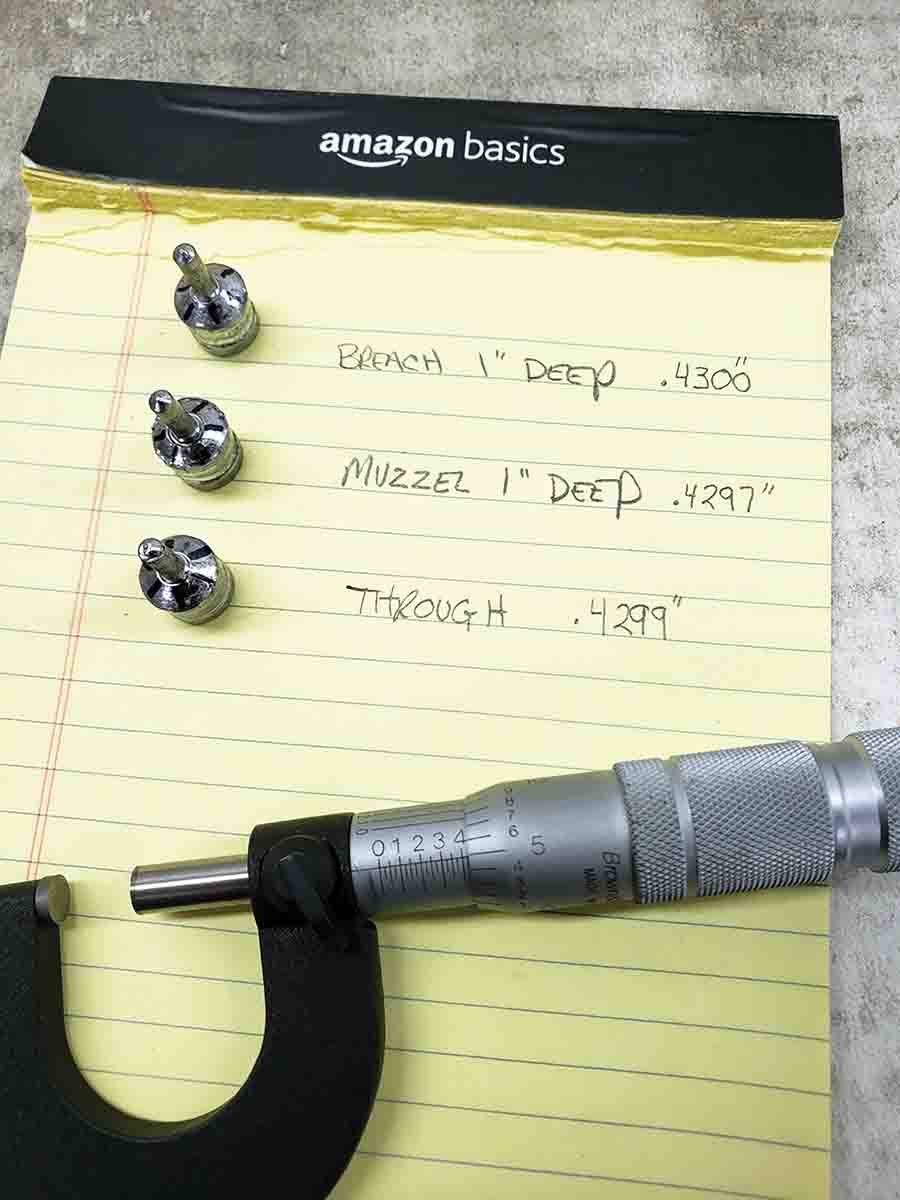

Royal then tapped Mike Venturino’s experience with black-powder cartridges. “Mike said 44-40 barrels he’d slugged mic’d .427 to .431 inch, and that to deliver good accuracy, bullets had to match the bore. Ideally, the hard-cast bullets I prefer would measure a thousandth over groove diameter.”

While a bore of .430 of an inch groove diameter can spin .428-inch lead bullets, they won’t seal it. Not only will accuracy suffer from skidding; hot gas skirting the shank will melt its surface, leading the bore and further impairing accuracy. Working backward from the bore to the cartridge case, Royal ordered .431-inch diameter bullets from Oregon Trail Bullet Co. “They were beautiful, though I noticed a shank-diameter lip ahead of the single crimping groove. Other 44-40 bullets I’ve used went right to the ogive ahead of that groove, or appeared to. A rifle must be throated for that lip, because the crimp won’t allow deeper seating for a short throat.”

Pressing a .431-inch bullet into new brass sized in a standard RCBS die, my pal produced a cartridge bulged by the bullet in front of the neck. The round chambered just fine, but when he extracted it without firing, he noticed deep rifling marks in the lead’s lip forward of the crimp groove. “That contact would be a problem if it tugged bullets free. Roll-crimped in the groove, the bullet was secure in recoil. But I feared a hard pull from the lands might stick it in the bore.” And so it did, after Royal cycled a few cartridges in and out. “A mess.”

Another challenge is sizing cases without overworking the brass. Reaming the neck of the sizing die to .440 reduced sizing compression on the brass, .0065 thick at the mouth, while permitting expansion to .428 of an inch with that figure in mind, and on Mike’s advice, Royal got a die set for the 44 Russian (which uses .429-inch bullets) and pirated its expander for his sizing die. “Result: A good grip on .431-inch bullets without squeezing the dickens out of fired cases.”

Loads from the tweaked tooling gave Royal a case that appeared almost straight. No bullet bulge. After firing, oddly enough, the case wore the 44-40’s slight shoulder. I concluded the Miroku’s chamber was generous. Royal agreed.

The bullet lip wasn’t a problem as long as every round chambered was fired. In fact, it may have contributed to the fine accuracy Royal is getting from that carbine. With enough Winchester 231 powder to send bullets at 1,280 fps, he’s stacking shots, tearing one ragged hole at 25 yards. But, he said, “That throat is about to get reamed. I’ll go just deep enough that my bullets don’t engage the lands – maybe an eighth inch. Then I won’t have to fret about pulling bullets when jacking out loaded rounds.”

His journey handloading for a 44-40 rifle with a .430-inch bore isn’t over. “Now that we’ve cleared all the hurdles,” he said, “This ’92 and I are gonna spend some time together. I bought 2,100 of those hard-cast .431-inch bullets, and they need to fly!”