.25-06 Ackley Improved

Loads for a Custom Mauser 98

feature By: R.H. VanDenburg, Jr. | February, 17

Parker O. Ackley was a custom gunsmith and an exceptionally active experimenter. Prior to World War II, he operated out of Trinidad, Colorado, but his most known address in the postwar era was Salt Lake City, Utah. He had more cartridges with his name attached than any other known wildcatter in his era. Despite the distance of time, some of his developments – notably the .30-30 Ackley Improved, the .257 Roberts Ackley Improved and the .280 Remington Ackley Improved – enjoy considerable popularity today.

A wildcat cartridge is one that is not chambered by major manufacturers nor is loaded ammunition available from major

The second category includes the “improved” cartridges. Here a parent cartridge has its chamber opened up to reduce the original body taper and to sharpen the shoulder angle. The parent cartridge is then fired in the improved chamber, resulting in a new wildcat cartridge. All of Ackley’s cartridges were formed in this manner, including the .25-06 Ackley Improved.

The third category involves the re-forming of an existing case. A parent case is selected, usually shortened, expanded, the shoulder, if there is one, set back and the neck sized to the appropriate diameter. Frequently special forming dies are required to establish the desired case shape in stages. Neck thickness may have to be reduced through reaming. Among the many cartridges developed by individual wildcatters or factory ballisticians employing this practice are the Weatherby cartridges smaller than the .300 Weatherby Magnum. All are based on a shortened and modified .300 H&H Magnum belted case.

After all these efforts, cases must still be fireformed in the new chamber and often creative methods must be established to secure the case head firmly against the breech before firing. To make matters more complicated, often there is little to go on with respect to the appropriate powder or powder charge. All in all, the category is not for the faint of heart, the light of pocketbook or the foolish.

Should a wildcat cartridge gain factory acceptance, of course, normal factory case forming dies are developed to produced finalized cases without any of the intermediate steps.

The .25-06 cartridge was introduced circa 1920 by Adolf O. Niedner. Niedner was a gunsmith, manufacturer and experimenter. Originally located in Massachusetts, he later moved to Dowagiac, Michigan. The cartridge modification consisted of simply necking the .30-06 case down to accept a .257-inch bullet. The original .30-06 shoulder angle of 17 degrees, 30 minutes was retained as was the original body taper, a perfect example of the “category one” wildcat cartridges described above.

Wildcatters began pulling at the threads of the cartridge almost immediately. The general course was to “improve” it by reducing body taper and sharpening the shoulder angle. Few improvements were considered successful. Even Ackley himself seemed to question the efficacy of improving the cartridge any further. In the 1962 Gun Digest in his article “Are Wildcats Dead?” Ackley stated, “. . . there have been numerous blown out or improved versions of the .25-06 but in the writer’s experience none compare to the original.” Ackley went on to include his own version in this critique.

That is only part of the story, however. In the article Ackley gave a list of load data for 87-, 100- and 120-grain bullets using various powders for the Niedner-standard .25-06. For the 120-grain bullet, his maximum 4831 powder charge was 57.0 grains for 3,101 fps. His maximum load for 4350 was 50.0 grains for 2,935 fps. These same loads and velocities appeared in the Speer Manual for Reloading Ammunition, Edition 7 (1966) and 8 (1970) as having been derived from a 25-inch barrel using government issue (.30-06) cases and CCI 200 primers. In the 9th Edition (1974), five years after Remington had legitimized the cartridge, Speer had cut the 4831 maximum load to 50.0 grains for a velocity of 2,971 fps from a 24-inch barrel, using Remington cases and Remington 91⁄2 primers. At the same time, the 4350 load had been cut from a previous maximum of 52.0 grains for 3,042 fps in Editions 7 and 8 to 48.5 grains for 2,960 fps.

All this was explained in Handloader No. 43 (May-June 1973) and No. 107 (January-February 1984) in Ken Waters’ “Pet Loads” on the .25-06 Remington. Prior to 1973, the only 4831 powder available to handloaders was that from Hodgdon. In that year, DuPont introduced its IMR-4831 in canister grade. Prior Speer manuals had used Hodgdon’s 4831; in the 9th Edition, Speer switched to the faster-burning IMR-4831. Also, the earlier editions had been developed in a Model 70 Winchester with a long-throated chamber designed to seat the 120-grain Speer softpoint bullet with its base even with the base of the neck. The now-standard SAAMI-approved dimensions demanded such a bullet be seated deeper into the case body. In its 9th Edition, Speer employed a standard-dimensioned Remington Model 700. The Winchester had a 25-inch barrel; the Remington, a 24 inch.

So where does all this leave us? Is the .25-06 Ackley Improved really an improvement over the standard .25-06 Remington? It seems to me it depends on where you start. In testing I easily got 200 fps or more out of the improved cartridge, but you need to understand how I did it.

Let’s go back to Waters once more. In Handloader No. 184 (December-January 1997), a reader wondered why there were so little .25-06 Ackley Improved load data. Waters responded by saying it was unnecessary. He explained the increased capacity of the improved case with some incorrect figures, such as stating the diameter of the improved case at the shoulder is .460 inch, when all Ackley Improved cases based on the .30-06 size case head are listed as .453 to .454 inch, depending on source. The essence of his reply, however, was spot on. He suggested the owner of the Ackley Improved version simply take the maximum load for a given bullet and powder in the standard .25-06 and, starting at 3.0 grains below it, increase charges one grain at a time until the listed maximum is reached, then by .5-grain increments, keeping in mind that a 2.5- to 3-grain increase is the ceiling. Somewhere in that -3 grains to +3 grains, the reader would find his rifle’s sweet spot.

A friend recently bought a custom Mauser Model 98 in .25-06 Ackley Improved. The receiver is pure 98 with “GEW98” on the left side rail. The barrel, unmarked, is 26 inches long. A Bell & Carlson synthetic stock and an old Redfield 3-10x scope complete the rifle. I’m told it was built by a student at the Colorado School of Trades. My friend purchased it from a neighboring ranch hand and offered to lend it to me for wringing out and developing this article. I immediately accepted.

The rifle came with several 50-round boxes of loaded and empty cases already fireformed to Ackley Improved chamber dimensions. Also included was one lonely .25-caliber neck sizing die. The loaded rounds consisted of Speer 87-grain TNT bullets over 60.5 grains of Reloder 22. A velocity notation was 3,600 fps.

My first step was to acquire a box of .25-06 Remington factory ammunition and 120-grain bullets. Remington lists these at 2,980 fps from a 24-inch barrel. Expecting to lose some velocity from firing in the improved chamber and to gain some because of the longer barrel, my recording of 3,002 fps seemed about right. When shooting those 87-grain loads that accompanied the rifle, I got 3,434 fps when shot over an Oehler Model 35P chronograph.

Next, attention was turned to measuring the increased capacity of the improved case. Remington cases are heavier, at 193.2 grains, suggesting less interior capacity than the Winchester cases weighing 180.5 grains, that were used throughout the testing.

In attempting to determine the actual increase in internal capacity of the Ackley case after fireforming, I concluded, with the 120-grain Speer bullet seated to a depth of .365 inch (overall loaded length of 3.200 inches), the improved case was larger by .021 cubic inch, or 8.8 percent. This translated to about 4.0 grains of IMR-4831, but that would not necessarily be a safe load.

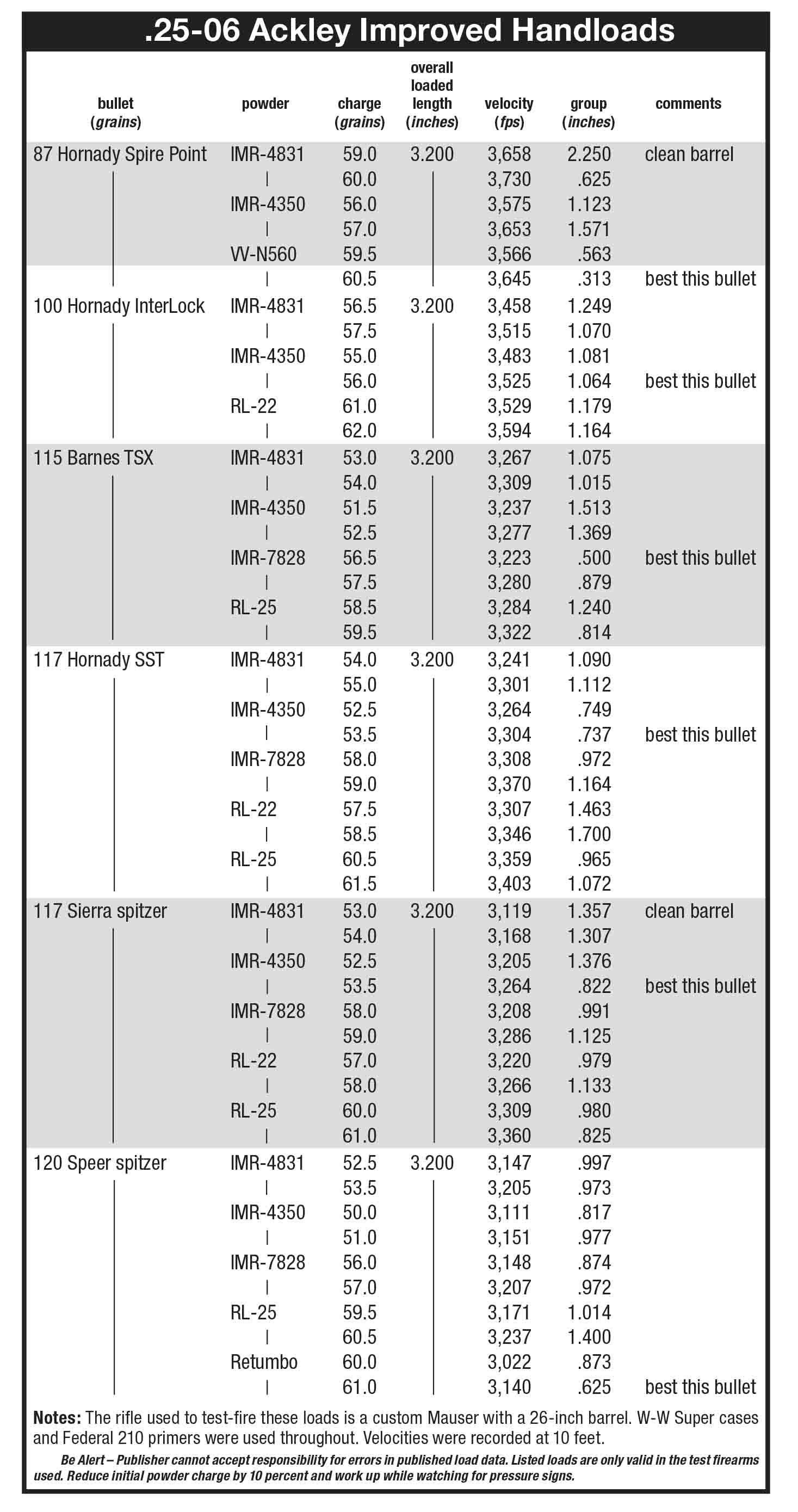

Following Waters’ suggestion, more or less, five rounds were loaded with IMR-4831 under the Speer 120-grain bullet with Federal 210 primers and powder charges that ran from 48.0 to 55.0 grains. Fifty grains of IMR-4831 is the maximum powder charge with this bullet in several manuals for the standard .25-06 Remington. I went as far as I did because of a lack of any excess pressure signs but eventually concluded that the sweet spot was 53.5 grains for a velocity of 3,209 fps and an extreme spread of 17 fps. This is close to Waters’ estimate and applies to my barrel only.

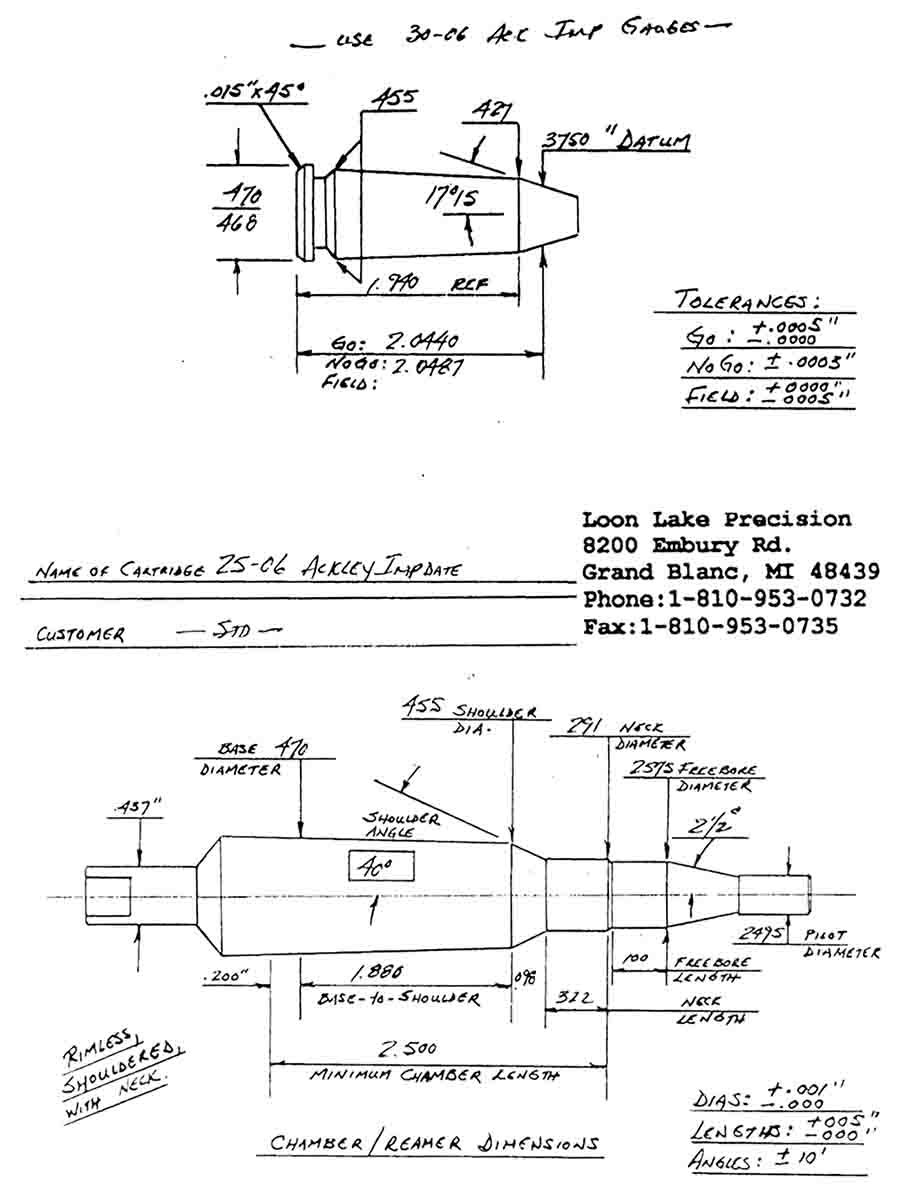

It troubled me a bit that the blown-out shoulder dimension of Ackley Improved cartridges based on .473-inch case head cartridges varied in the different reloading manuals, usually ranging from .453 to .454 inch. Troubling also was the fact that I did not know exactly what a .25-06 Ackley Improved chamber was supposed to look like. One day, perusing Brownells’ catalog revealed the company carries a large array of chambering reamers made by Dave Manson Precision Reamers. Going down the list, I don’t know what shocked me more, the absence of the .30-30 Ackley Improved reamer or the inclusion of the .25-06 Ackley Improved. I quickly called my contact at Brownells and asked if he had a dimensioned drawing of the cartridge chamber. He didn’t, but he put me in contact with Dave Manson’s company.

Upon explaining what I wanted, and why, the nice lady who answered the phone said it would be in the mail the next day. It was, and a picture of the drawing appears herein. As can be seen, the shoulder diameter is .455 inch with a tolerance of +.001 inch and -.000 inch. Normal contraction after firing should leave cases at .453 to .454 inch. Occasionally when measuring cases after firing, shoulder dimensions of .455 inch were noted. Whether this means my chamber is slightly oversized or some of the cases have been loaded often enough to lose some of their elasticity, I don’t know. Even without a full-length sizing die for the cartridge, at no time did I experience any difficulty in chambering loaded rounds. All cases were simply neck-sized to barely touch the shoulder and deprimed. Bullet seating was done with a .257 Roberts seating die.

The next area of concern was with the pressure ring. After firing factory .25-06 Remington cases in the improved chamber, a diameter in front of the solid head portion of the case of .472 inch was noted. The maximum .25-06 Remington loading manual recipe of 50.0 grains of IMR-4831 under a 120-grain Speer bullet loaded in a fireformed case and fired in the improved chamber produced a reading of .4735 inch. My best Ackley Improved load of 53.5 grains under the same bullet produced a diameter of .4745 inch. In the end, anything that did not exceed .4750 inch was considered acceptable; anything more was considered over maximum for my rifle and is not included in the accompanying table.

Another point of consideration was that the SAAMI pressure limitation for the .25-06 Remington is 53,000 CUP. The same case necked to accept .277-inch bullets (.270 Winchester) has a pressure limitation of 57,300 CUP. This seems to me to provide a modest safety margin when attempting to maximize performance without exceeding .25-06 pressures.

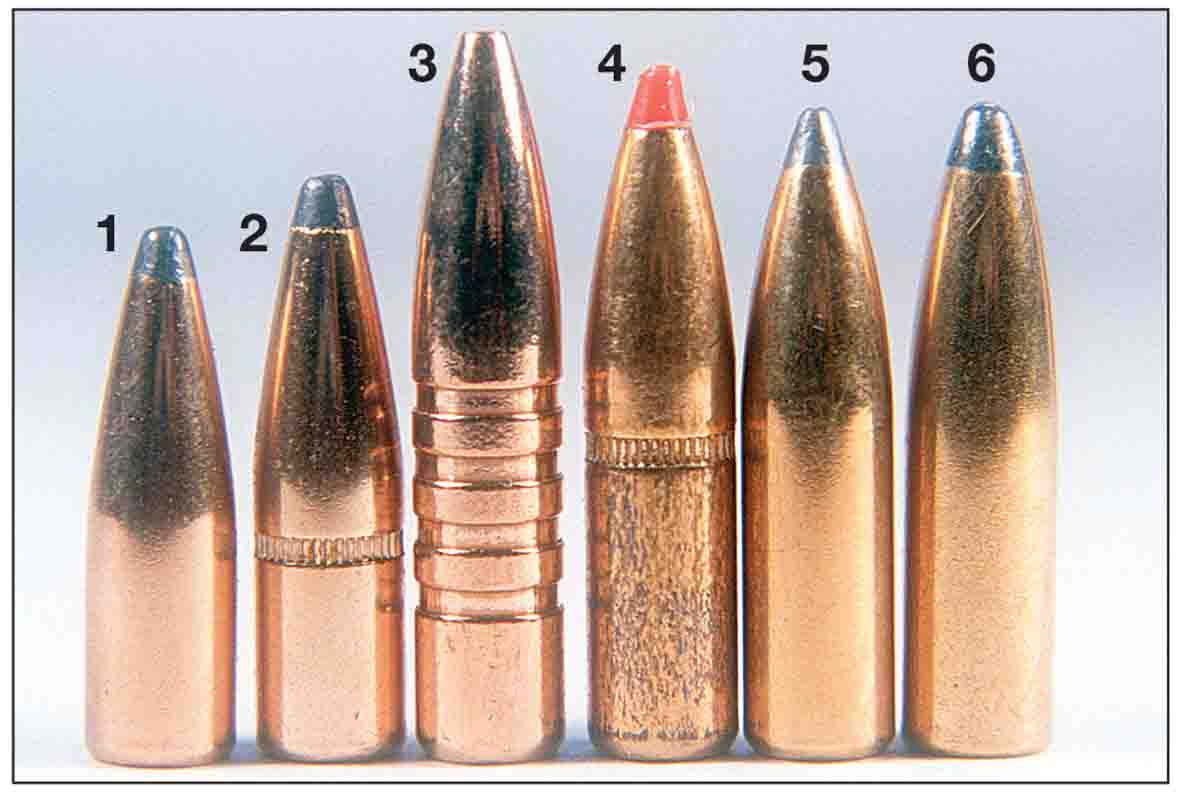

Several powders and a variety of bullet weights from 87 to 120 grains were worked with. Seeing the cartridge as best suited for our smaller big game, such as antelope and deer, sheep and goats, I concentrated on the heavier end of the bullet weight spectrum. That said, I know several people who consider the .25-06 Remington and, by extension, the Ackley Improved version, as ideal for long-range coyote hunting, which may explain the many loaded 87-grain rounds that came with the rifle.

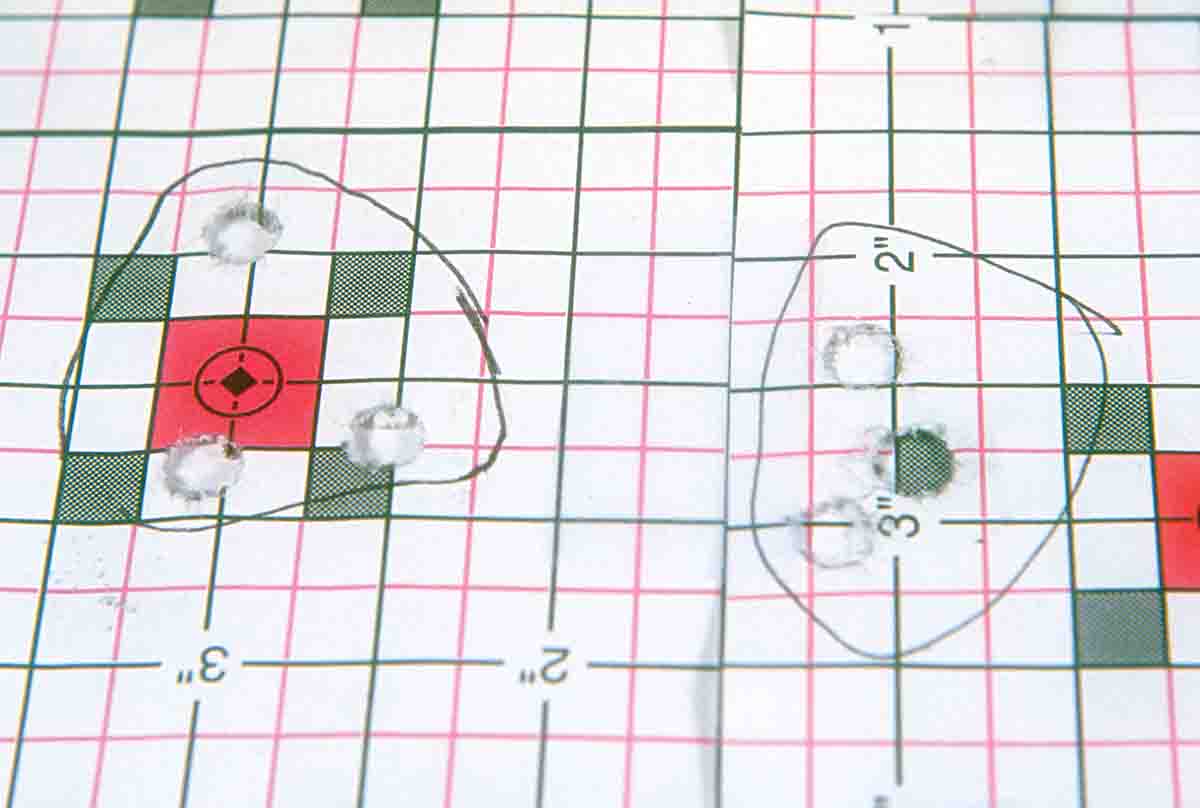

Of all the powders tested, none failed to produce sub-1-inch groups with at least one bullet. Likewise, no bullet failed to produce sub-1-inch groups with at least one powder. All were three-shot groups. For all that, if I had to restrict my .25-06 Ackley Improved powder selection to one, it would be IMR-4350 with IMR-4831 and IMR-7828 nipping at its heels. Alliant Reloder 22 and Hodgdon’s Retumbo would get serious consideration if limiting bullet selection to 115 to 120 grains. For 87-grain bullets, no powder surpassed Vihtavuori N560.

All this is offered with the realization that another rifle may have a different “sweet spot,” favorite powder or preferred bullet. Beginning low and working up carefully is still the accepted process.