Reloader's Press

.44 S&W Special Versus .45 Colt

column By: Dave Scovill | February, 17

In the 30-odd years I have been writing about handguns, this is the column I thought about writing but chose not to, mostly because for many of those years, the .45 Colt, in terms of bullets, reloading dies and sixguns, was at somewhat of a disadvantage. The exception was in 1971 when Ruger came out with the Old Model Blackhawk .45s that were manufactured to closer chamber and throat tolerances than the age-old Colts. The Rugers were stronger too, making it possible to match velocity and energy numbers produced by a hopped-up .44 S&W Special in a Colt SAA using bullets, cast or jacketed, of similar weight.

By the late 1970s, about the only fair comparison between the .44 Special and the .45 Colt was limited to factory loads with a 246-grain roundnose lead bullet at roughly 760 fps and a 250- to 255-grain conical lead/alloy slug at maybe 800 fps. At the time, it wasn’t unusual for some scribe to show some respect for the older .45 Colt loads, especially the post 1880 UMC 40-grain, black-powder load that packed more punch than the .357 Magnum could muster post-1936, but the factory .44 Special load with the 246-grain roundnose lead slug was pretty much condemned all around for anything except target shooting.

Of course, the major difference between the .44 Special and .45 Colt was when it came to handloads, whereupon some claimed the former was the most accurate and powerful big-bore cartridge extant pre-.44 Magnum, while the latter rarely made honorable mention. The caveat, however, was that it was pretty routine for scribes to quote the legendary Elmer Keith regarding the potent .44 Special, to bolster accuracy and power comments, but were pretty much left to quoting their neighbor or a distant relative when it came to laudable comments regarding the older .45.

All the above is a brief summary of the situation regarding the .44 Special and .45 Colt as gleaned from the pages of various shooting magazines I managed to find in the PX on U.S. Naval bases scattered around the Pacific in the late 1960s.

Upon release from active duty, considering the almost cult-like status some writers bestowed on the .44 Special, it was likely a stroke of luck to locate two in the same pawn shop, a Smith & Wesson Second Model 44 Hand Ejector Target with a 6-inch barrel and a second generation Colt Single Action Army .44 Special with a 7.5-inch barrel. The Colt .45s, it seemed, had been gobbled up by collectors, and it took awhile to locate a .38 S&W Special that had been converted from some unknown – at the time – chambering years before. A gunsmith friend converted it to .45 Colt in early 1973.

Since I wasn’t set up to cast bullets in those days, jacketed bullets had to suffice until an order of Markell cast bullets from San Francisco was placed for Keith-Lyman type designs, 429421 and 454424, which I assumed were cast from Lyman No. 2 alloy but, in retrospect, were more like one to 16 (tin to lead).

Once my shooting skills were honed, a set of Smith & Wesson Magma stocks was filed down and sanded to fit my hand much better than the factory wood, and both Colts were fitted with slightly oversized stocks.

It really didn’t take all that much time or effort to get the Smith & Wesson Second Model 44 Target to shoot quite well, and for awhile at least, it was the first choice for hunting small game and varmints at ranges out to 100+ yards or so using Markell cast bullets. Later, my bullets cast from a Lyman mould 429421 using an alloy similar to Lyman No. 2 seated over 13.5 grains of 2400 in Winchester cases with Federal’s 150 primers proved to be the most accurate load in both the S&W and Colt .44s.

In comparison to the .44 Special, the .45 Colt proved problematic, mostly owing the oversized, .456- to .457-inch chamber throats that are common to Colts from 1873 to present day, with the exception of some early Model Ps with .450-inch throats. When Colt reduced barrel groove diameters from .454 to .451/.452 inch sometime after World War II, the situation didn’t improve much. To compound problems, it seemed folks generally resisted sizing bullets to fit, or at least come somewhat closer to, throat diameter than .452-inch cast or jacketed bullets provide. Then they complained about mediocre accuracy, especially with commercial hardcast bullets.

More importantly, all four loads were at the very least compatible with best accuracy produced by the S&W and Colt .44 specials, the former with .434-inch chamber throats and .429-inch barrel and the latter with .432- and .427-inch measurements, respectively, and share a common .005-inch difference with the .45 Colt at .456 and .451 inch, respectively. This is/was interesting since the oversized chamber throats in the .45 Colt sixguns receive most of the blame for mediocre accuracy, but from what I read in various gun-related periodicals, are generally ignored for the .44 Special.

So, what’s going on here? To begin, the first S&W .44 Special Triple Lock, or First Model, was among the finest revolvers ever produced, while the Colt Model 1873 was a bit of a clunker by comparison, especially in terms of trigger pull and sights. On the other hand, Elmer Keith’s No. 5 and Long Range Colts were among the finest of their breed and certainly competitive with the Triple Lock Target .44s and the long list of N-frame .44 Specials that followed. So, in factory condition, any comparison between the Triple Lock and Colt SAA is like apples to oranges.

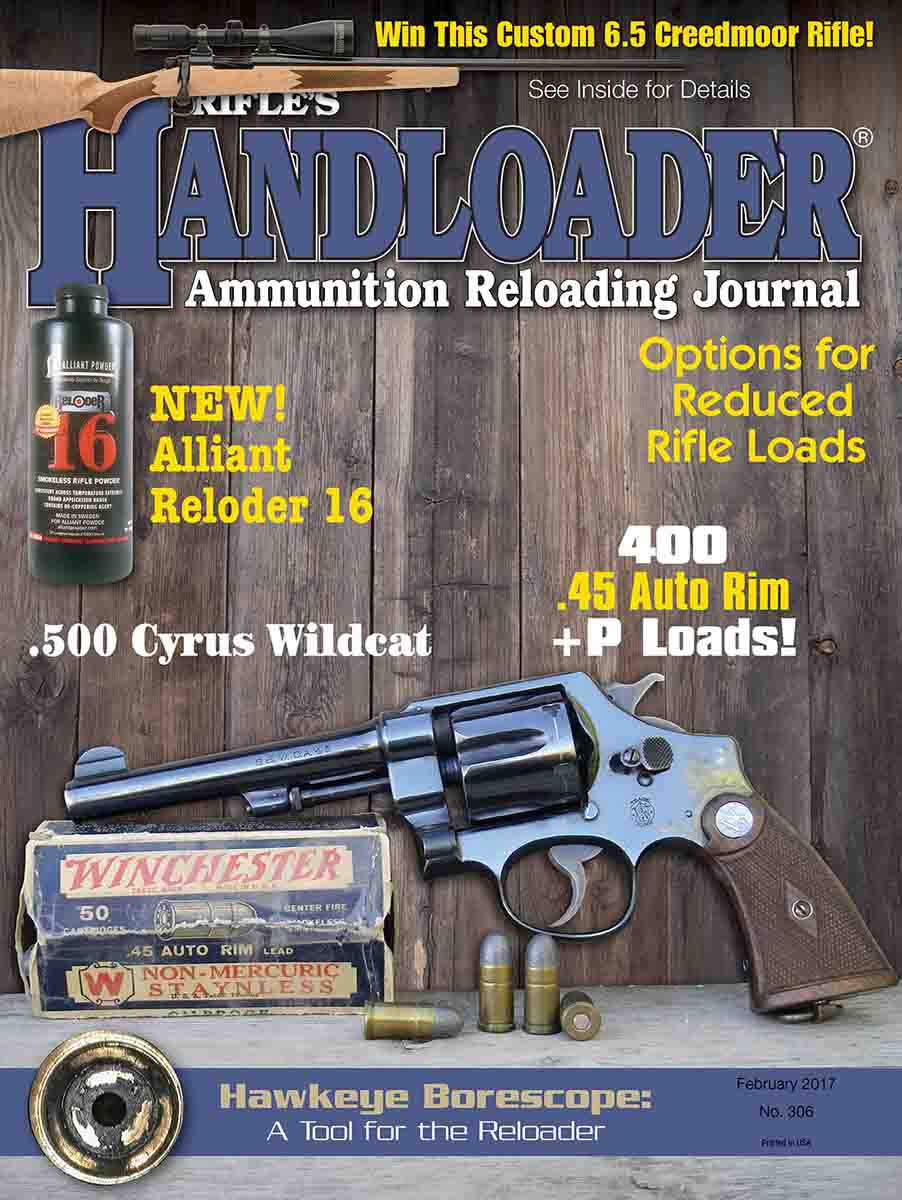

To keep the comparison closer to apples to apples, it makes more sense to compare the Colt New Service Target that was chambered for .44 Russian, .44 Special, .45 Colt and .455 Eley, among others, with the Triple Lock. Most were Russians, one of which made a world record 100-shot, 20-yard score in 1900, and another fired a world record perfect score in 1907. These accuracy standards, however, were never supplanted by the .44 Special, Colt or S&W. So where did the .44 Special get its reputation for accuracy? The answer is summed up with two words: Elmer Keith.

This was back in the days when .45 Colts still had .454-inch barrel groove diameters, averaging around .002 inch smaller than chamber throats, which likely tightened considerably any accuracy comparisons between the .44 Special and .45 Colt. So while the .45 Colt was largely considered a martial arm from 1873 until World War II that was designed to neutralize a two-legged assailant at relatively short distance, it wasn’t until the advent of shooting games, circa 1980s, with .451-inch barrels, that accuracy complaints began to surface by folks who insisted on using relatively hard cast bullets sized to within .002 inch of barrel diameter, vice using a more appropriate alloy like one in 16 (tin to lead) sized to fit chamber throats. Then too, some factory loads still have .455-inch cast and jacketed bullets that shoot quite well in most modern .45 Colt revolvers, foreign or domestic.

The disclaimer is that the .45 consumed nearly 1,100 rounds while the .44 fired just under 600 rounds, mostly because correspondence over 26 years as editor of Handloader suggests the .45 Colt is more popular than the .44 Special. This is interesting, since the reputation for overall accuracy associated with the .44 Special doesn’t necessarily translate into popularity. Apparently, the Colt SAA .45 Colt is a piece of history, accuracy or not, while the .44 Special is the cartridge Elmer Keith dropped like a hot rock in 1955/56 when the .44 Magnum came out.

***

(1935-2016)