Hawkeye Borescope

Seeing is Understanding

feature By: Terry Wieland | February, 17

Even after the shot is fired, many of the areas we would most like to look at, to get some firm answers, cannot be readily scrutinized. Looking down the bore of a rifle reveals little beyond whether there are powder particles left in it, because what is seen is not the bore itself but the reflection of light off its metal surfaces. The same is true when examining the interior of a bolt to see if the walls are rough, or if oil has solidified to the point where it’s interfering with the striker fall.

Handloaders have their own problems in this regard. Much as we might like to examine the interior walls of a fired case to see whether there is corrosion, it’s awfully difficult to do. Shining a light in through the mouth of a bottleneck case, while manipulating it to see what the light is shining on, reveals about the same amount of information as holding a rifle bore up to a light and looking through it . . . which is to say, not much.

Forensic investigators section barrels and cartridge cases to study their surfaces under microscopes, which may be informative, but it’s pretty final. And, it doesn’t help much in analyzing why your own rifle is shooting poorly.

One particular bugaboo for those who play around with wildcats that involve fireforming, or using older rifles that might have generous headspace, is determining if a case is on its way to a head separation. For those who have never had the pleasure, a head separation on firing is one of the less edifying experiences. With a good bolt action, or even a strong levergun, it’s not necessarily dangerous, but on a target range it’s an inconvenience, and it could well ruin a hunting trip. Some years ago, hunting bison in Colorado, my companion was shooting a Winchester ’86 chambered for the .475 Turnbull. She

The .475 Turnbull cartridge in question was a handload of mine, and after the fact I managed to figure out what had happened to cause the separation. When I got home, I examined carefully all those cases, found others that were on their way to a separation and got rid of them. But – a big but – I should have done that before, not after.

About a dozen years ago, I invested in a Hawkeye borescope, an optical device for examining the interiors of rifle bores and similarly hidden surfaces. Made by Gradient Lens Corporation of Rochester, New York, the borescope has been marketed to shooters for about 20 years. I never felt I needed one until I ventured into benchrest-style shooting and wanted to check bores for lingering, stubborn cuprous fouling. At the time, the Hawkeye borescope was not cheap – something along the line of $500, as I recall – which is a lot of money just to check for cuprous fouling. I muttered something about the interests of journalism

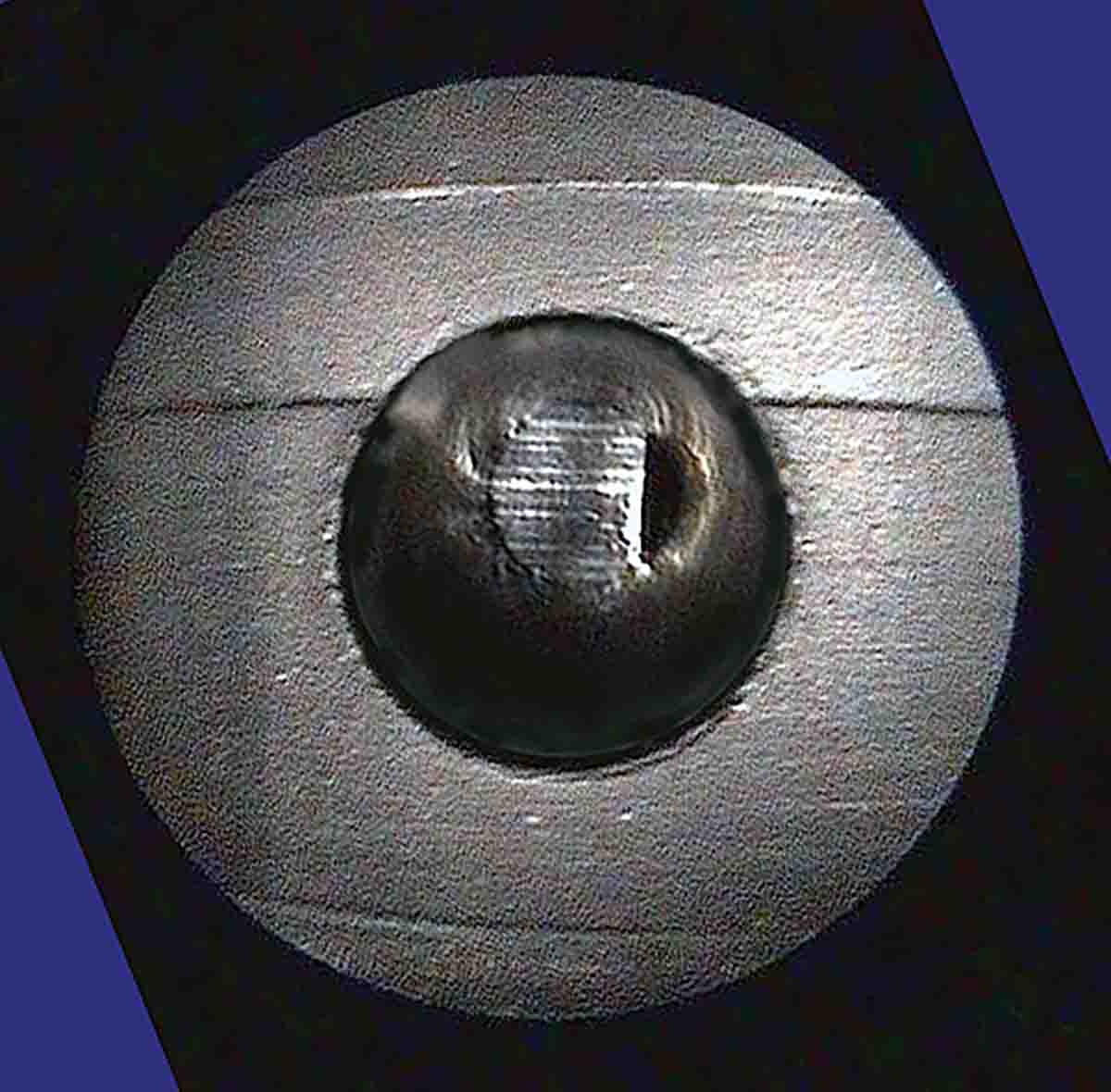

The Hawkeye borescope is a precision instrument, but it’s not awfully complicated, and, good news for the technophobes, it need not have any digital appendages. You don’t need to program it. If you conquered the use of a microscope in Grade 9 biology, you can master the borescope. It consists of a narrow (.175-inch) steel tube with tiny lenses, 17 inches long. It is, in effect, a miniature telescope, or maybe it would be more correct to call it an extendable microscope. It is focused by rotating the eyepiece. A flashlight attaches at right angles, and the light is reflected down the tube to illuminate the surface you want to examine. By looking through the eyepiece, you can directly study a surface, such as the web or flash hole of a fired cartridge. If you want to examine the side wall of a rifle bore, there is a slightly larger (.190-inch) tube, fitted with a tiny mirror, that slips over the smaller tube and allows a 90-degree view. There are other attachments, such as a right-angle viewer that makes for more comfortable use when looking at a rifle bore when the rifle is in a cradle.

Gradient Lens recently introduced a lower-priced version of the Hawkeye borescope intended specifically for shooters (the

When Gradient began in 1995, it offered only one model of borescope. Today, it has more than 80 different variations: rigid, flexible, with and without tiny video cameras and attachments to display results on video screens and computers. The company’s 32-page catalog (www.gradientlens .com) gives a range of accessories to satisfy even the most depraved of the gadget-minded, but the simple Shooting Edition of the borescope will handle almost anything you need to do.

Some applications for which I now use my borescope routinely are common to any shooter. One is examining the rifling just forward of the chamber, to check for erosion; another is looking at the neck of the chamber itself. The interior of a bolt, which was terra incognita for most of us before, can now be examined carefully for rough spots or caked lubricant that slows down striker fall, or causes misfires. There are also nooks and crannies in actions of every sort that can bear more scrutiny than they normally get.

Something that gets little or no attention is the interior of loading dies. Working with wildcats or case-forming obsolete cartridges can cause all kinds of unusual wear and tear, including little mishaps like torn-off rims that require dismantling the die and pounding out the offending case. This kind of activity, which is never recommended by the die manufacturer, can result in dies that are scratched inside and will later cause problems. It is best to find out before investing in a new batch of cases. I have even used the bore-scope to check for log-jammed primers in the expended-primer tube of my loading press. Believe me, it’s a lot easier than unbolting the press from the bench and up-ending it to clear them out later.

Earlier, the issue of examining cases for signs of incipient case-head separation was

The most common cause of this problem is case forming. My own worst experience with such case stretching has been in fireforming .256 Winchester brass, either from .357 Magnum or .22 Remington Jet brass. At times, depending on the method, wastage rates reached 50 percent. Examining the inside of the cases reduced that considerably.

There are so many possible applications for the Hawkeye bore-scope in handloading that it is impossible to list them all. One thing I’ve found, however, is that while the borescope reduces much of the mystery and replaces speculation with visual evidence, it does not reduce the fascination of the whole business one little bit. If anything, it works the other way around.