.257 Weatherby Magnum

Newer Bullets and Powders

feature By: John Barsness | August, 22

Its acquisition coincided with the introduction of the Barnes Triple Shock X-Bullet, which seemed to fit the characteristics of Roy’s .257. Monolithic bullets tend to kill quicker when driven at higher velocities, yet also tend to ruin less venison than lead-core bullets. The TSX also solved the copper-fouling problem of the original, ungrooved X-Bullets, and occasional poor accuracy when an X-Bullet’s diameter did not precisely match a specific barrel’s bore/groove diameter.

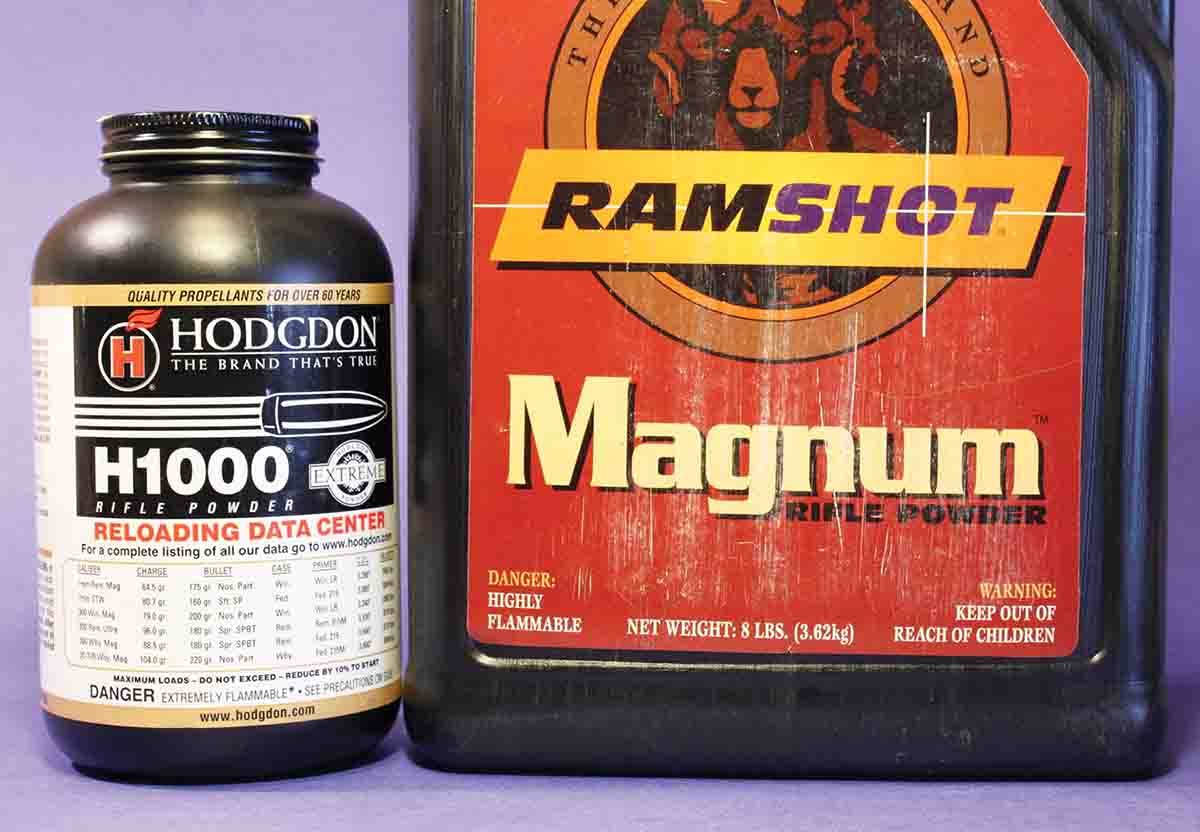

This also occurred shortly after the appearance of a new powder that worked very well in other rounds, Ramshot Magnum. My handloading notes indicate no other powder was tried, probably because the rifle didn’t arrive until October 1, when fall rifle seasons were already opening.

At the time, Ramshot had no data for the .257 Weatherby, but its pressure-lab folks offered some suggestions. The test-shooting began with Hornady 100-grain Spire Points (now apparently discontinued), starting with 71 grains and working up to 76 grains, which grouped well at a little over 3,400 feet per second (fps) from the Vanguard’s 24-inch barrel. With the same powder charge, 100-grain TSXs chronographed just over 3,500 fps – about what various loading manuals suggested as top velocity for 100-grain bullets with other appropriate powders.

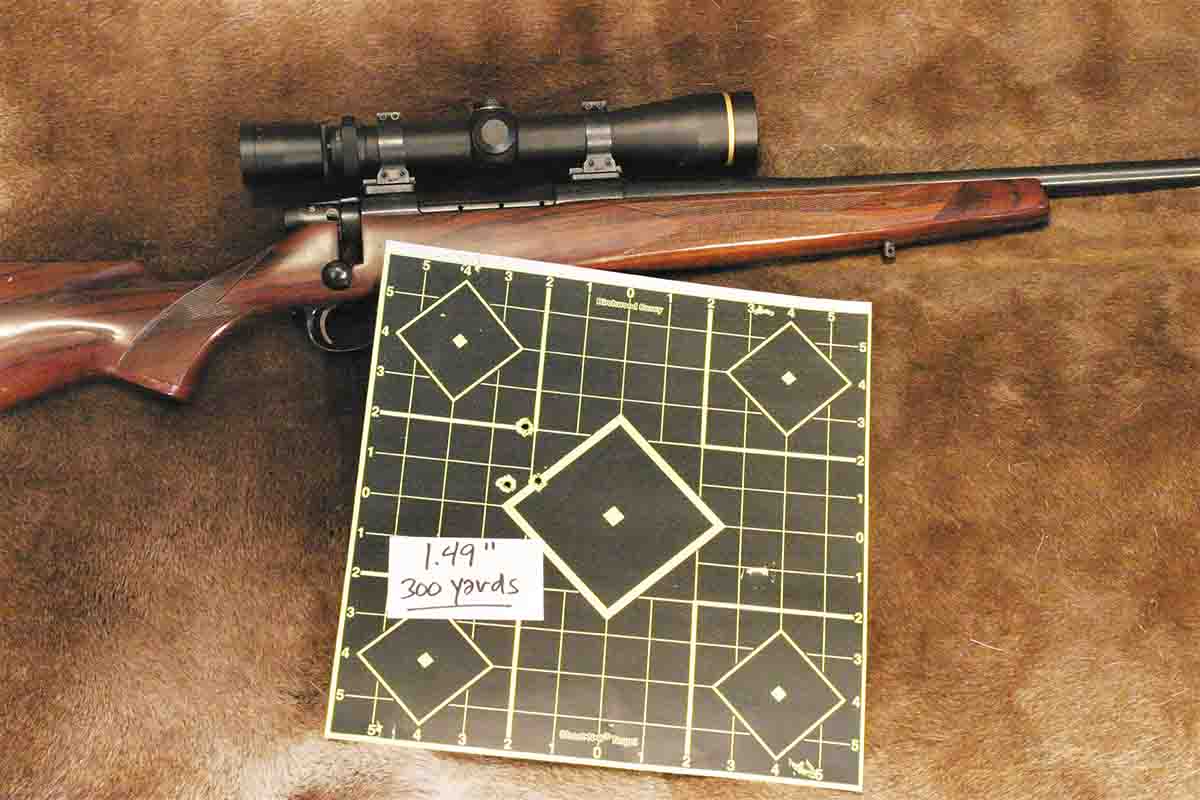

With the rifle sighted-in at 2.5 inches high at 100 yards, when range-tested at 5,000 feet above sea level, the TSXs landed about an inch high at 300 yards, where a three-shot group fired measured 1.49 inches. Point of impact was about 6 inches low at 400, but the first animal killed that far away (a pronghorn buck with 16-inch horns) lay bedded on a steep slope above me, which would cause the bullet to land a little higher. With the reticle held on the center of the chest, the TSX landed high in the lungs and cracked the bottom of the spine.

Of course, today such a flat trajectory supposedly isn’t required for longer-range hunting, due to scopes with very repeatable adjustments. The elevation turret can be twirled to compensate for the trajectory curves even of moderate-velocity cartridges such as the 6.5 Creedmoor – the round loved or hated by those hunters caring enough to have an opinion.

In 2007, I acquired another .257 Weatherby, a New Ultra Light Arms Model 28 made by Melvin Forbes. While some .257 Weatherby fans believe the cartridge requires a long barrel “to burn all that powder,” the 24-inch barrel on the Vanguard pushed 100-grain bullets far faster and flatter than any of my other .25-caliber rifles, including a custom .25-06 with a 26-inch barrel, so I asked Melvin to fit a 24-inch, No. 2 contour Douglas stainless barrel.

The NULA was ordered due to finding the Weatherby a little ponderous for some hunting. With a scope, sling and three rounds in the magazine, it weighed nearly 10 pounds – easy to shoot, but not ideal for, say, hunting the steep Missouri Breaks. The NULA weighs a couple ounces over 7 pounds with a 13-ounce scope in the aluminum rings that came with the rifle, an Uncle Mike’s Mountain sling and full magazine.

At first, I thought it might be handy to own both the heavy and light .257 Weatherbys, but within a couple years I never hunted with the Vanguard again, partly because the NULA was even more accurate. Since then, the NULA has also been used as a “test platform” for newer bullets and powders – but relatively few .25-caliber bullets have appeared due to the “fast-twist” 6mm and 6.5mm trend. Most factory .25-caliber rifles still come with 1:10 rifling.

My edition of Phil Sharpe’s Complete Guide to Handloading appeared in 1953 and contains Roy Weatherby’s early loading data for his

Roy probably did get 3,750 fps, because one basic ballistic rule with single-base powders like IMR-4350 is velocity increases at the same rate as the powder charge. Dividing 69 grains by 61 grains results in 1.13, and multiplying 1.13 times 3,364 results in 3,801 fps. However, Sharpe’s book does not list any pressures for Weatherby handloads, probably with good reason.

Hodgdon eventually quit printing hardcover loading manuals and now publishes data on the internet and in yearly magazines. The .257 Weatherby data in the Hodgdon 2022 Annual Manual lists nine powders for two 100-grain bullets, the Speer SPBT and Swift A-Frame. The top velocity is 3,575 fps from a 26-inch barrel, using the Speer bullet and 78 grains of Hodgdon H-1000.

While testing the NULA with newer powders and bullets, I contacted Ron Reiber, the long-time ballistic honcho at Hodgdon, who retired a couple years ago. Ron suggested Hodgdon H-1000 as the best all-around performer, and it worked very well, especially with the Nosler 100-grain E-Tip, which at the time had the highest listed ballistic co-efficient of any monolithic 100-grain, .25-caliber bullet. Even from the NULA’s 24-inch barrel, 76 grains of Hodgdon H-1000 got around 3,550 fps.

While the load table lists average three-shot groups at .47 inch, the last three fired to check the rifle’s zero went into .27 inch. To see if that was a fluke, after marking the target, I fired another round, which widened the group to .47 inch, so the average also includes one four-shot group. (This fine accuracy was probably due to very calm wind conditions – at least for Montana.) For the past several years, the rifle’s scope has been a Burris Fullfield II 3-9x 40mm with the Ballistic Plex reticle. The trajectory is maybe an inch flatter at 400 yards than the TSX in the Vanguard at typical pronghorn-hunting temperatures.

In the so-called “real world,” when started at 3,500 fps, any of these bullets will have a very similar trajectory out to 400 yards. Two different ballistic calculators showed a difference of less than 1.5 inches, at 50 degrees and 5,000 feet above sea level.

The same calculators also showed that there isn’t much difference in wind drift between the 100-grain E-Tip in the .257 Weatherby and the Hornady 143-grain ELD-X started at 2,700 from the 6.5 Creedmoor. In a 10-mph, 90-degree wind, the drift is essentially identical at 400 yards, and at 500 yards, is 1.8 inches less for the high-BC ELD-X, not enough to worry about. (The 143-grain ELD-X is cited because I have plenty of range and field experience with it in the Creedmoor, and 2,700 fps is the listed muzzle velocity of Hornady’s Precision Hunter factory ammunition – and also close to average with handloads for bullets in the 140-grain range.) This isn’t meant to put down the 6.5 Creedmoor, since my opinion tends toward the “like” side. However, it does demonstrate that high-muzzle velocity reduces wind drift considerably at “normal” hunting ranges, even with relatively low BC spitzers.

If you are among the vast majority of hunters who never shoots at big game beyond 500 yards, the only real downside of the .257 Weatherby is somewhat heavier recoil than the 6.5 Creedmoor. Another computer calculator indicates an 8-pound 6.5 Creedmoor with the 143 ELD-X load develops about 14 foot-pounds of recoil energy. An 8-pound .257 Weatherby with a 100-grain bullet at 3,500 goes about 21 foot-pounds – not what most hunters consider “magnum” recoil, since it matches 150-grain bullets at 2,900 fps from an 8-pound .270 Winchester. The remains quite ignorable even in the NULA, even for a hunter of my advanced age.

Of course, the .257 Weatherby handles bullets heavier than 100 grains and they also work well. I have used the listed Nosler 120-grain Partition with Ramshot Magnum out to 300 yards on pronghorns, and it tends to kill even faster than monolithics at 3,500 – and some hunters have found it works even on much larger game.

A decade ago, I hunted elk with three friends on a local ranch, and Tim Frampton killed a mature 6x6 bull with a single 120-grain Partition placed behind the shoulders with his Weatherby rifle. Now, the bull did run a few seconds before falling – or rather crashing – down the very steep slope, but apparently died on its feet before running head-on into a big Douglas fir. Oh, and the bullet exited. (Another friend recently killed a mature bull nilgai in Texas with a single Barnes 100-grain TTSX, which also exited. Come to think of it, I have never recovered a bullet from either of my .257 Weatherbys.)

Some real handloaders may notice the overall cartridge lengths listed in the handload table exceed the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) .257 Weatherby limit of 3.209 inches. This short overall loaded length puzzled me for a while, until realizing the cartridge came along shortly before the era when zillions of “war surplus” 1898 Mauser military rifles appeared in the U.S. at very low prices. This resulted in a major remodeling industry, with many being transformed into various degrees of “hunting rifle” – and the magazine length of some military 98s is a little over 3.2 inches. (However, this does not explain why the SAAMI maximum length for the .270 Weatherby is 3.295 inches, and 3.360 inches for the 7mm Weatherby – but there many mysteries in SAAMI standards.)

Some handloaders whine about the price of Weatherby brass, though it has been made by other companies. My ammunition supply, for example, includes a box of Federal .257 Weatherby factory ammunition, a gift from a friend, but I am also still using the same batch of Weatherby brass obtained along with the Vanguard in 2004. Annealing after every fourth firing keeps it working fine.

However, for those who prefer to handload for less money – or cannot find Weatherby brass, which is not uncommon during the increasingly frequent “shortages” in components – a simple solution exists: Cases for the ever-popular 7mm Remington Magnum can be easily converted by simply running them into a full-length .257 Weatherby die. I have done this several times with various brands, and none of the case necks became too thick for firing in standard .257 Weatherby chambers. Even cheapskates can afford that!

.jpg)