Cartridge Board

.38 Long Colt

column By: Gil Sengel | August, 22

American cartridge handguns of .38 caliber have always been very popular. If we note that the 9mm Luger bullet is only .003 inch smaller in diameter than a .38 Special, .38 caliber becomes the most used size today as well.

There is, however, a small error here. No real, .38 caliber U.S. handgun cartridges exist! Not one, not ever. Most are .37 caliber or less. One, the .38-40 Winchester is .39 caliber or a bit more depending upon who made the barrel. Our cartridge featured this time gives an opportunity to discover how some of this silliness got started.

The story begins in 1858 with Smith and Wesson’s (S&W) .22 Short rimfire cartridge and its revolver. It was immediately obvious that when made in larger calibers, they would make the percussion revolver as obsolete as a war chariot – and apparently, they did. One was the .38 Long rimfire intended for new revolvers and converting .36-caliber percussion guns to fire cartridges by replacing the cylinder and altering the hammer face. But how can a .36 caliber become a .38 caliber without changing the barrel?

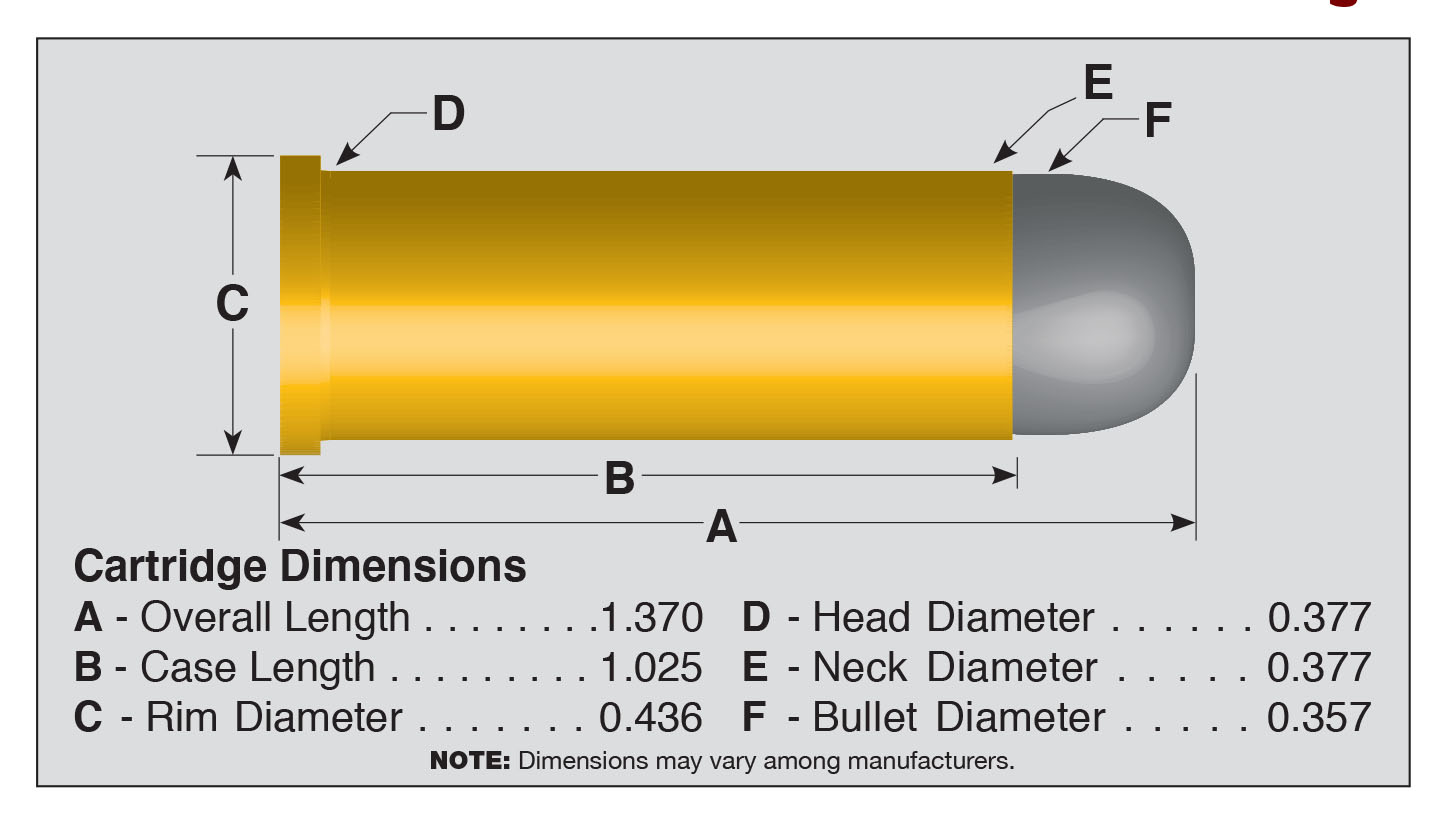

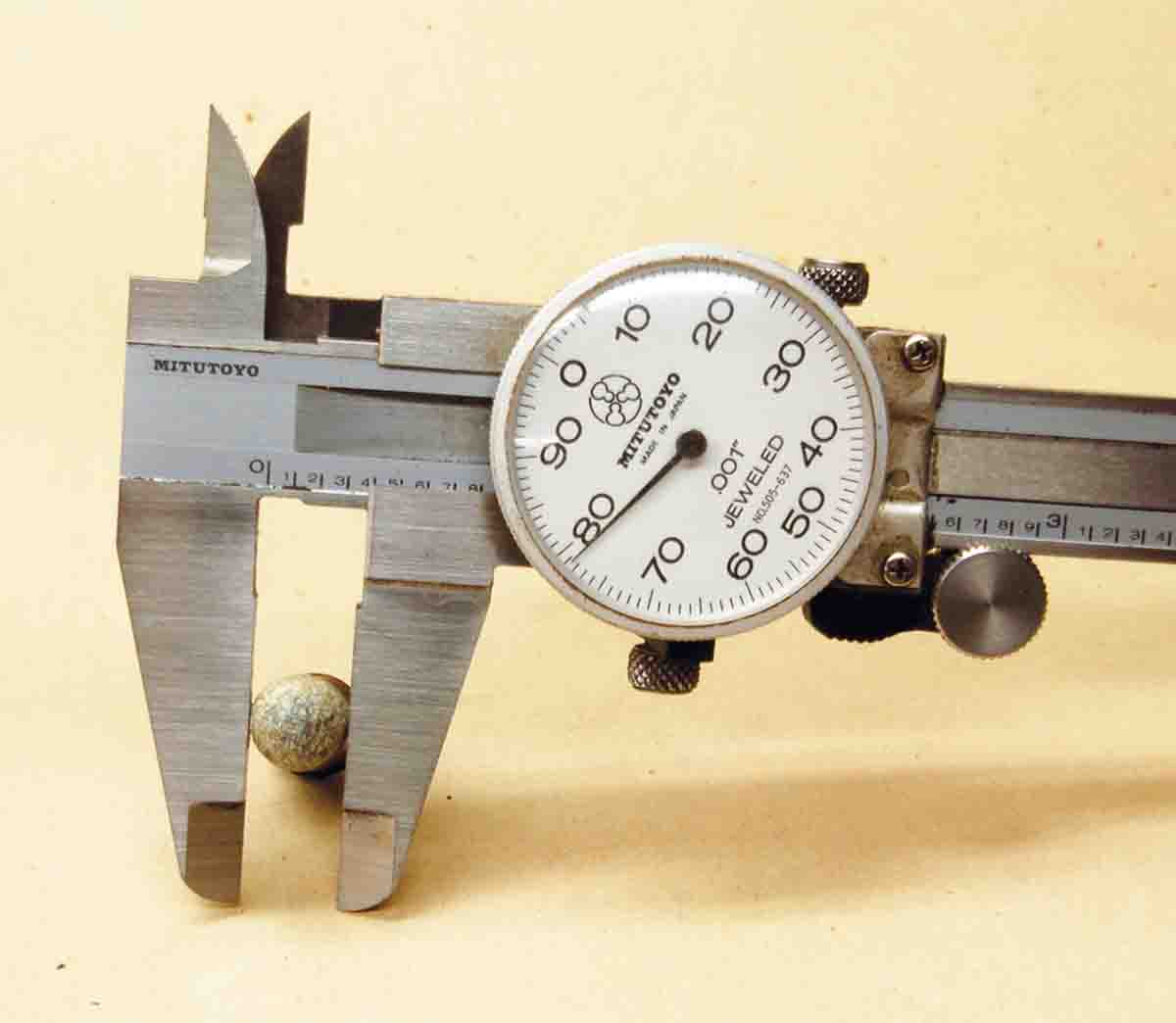

The word caliber is very old. It refers to the inside diameter of a hollow cylinder or inside diameter of a gun barrel before rifling and is also termed bore diameter. Percussion guns called .36 caliber use .375- to .380 inch roundballs. Bore diameter is thus about .370 inch or .37 caliber. The .38 Long rimfire used an outside lubricated bullet of about .379 inch, which makes bore diameter about .370 inch or .37 caliber!

Conversions worked fine, but folks had not done their homework. Smith and Wesson owned the Rollin White patent that covered a bored-through revolver cylinder. Obviously, this was mandatory for a cartridge revolver. No one could legally use this feature until the patent expired in 1872, by which time centerfire ignition had proven superior to rimfire.

Now was the time to correct the caliber inaccuracy. Cartridge confusion would have been impossible if one was rimfire and one was centerfire, but it didn’t happen. The .38 Long rimfire became the .38 Long centerfire in 1874. Then, the so-called .38-caliber cartridge world changed.

In 1876, Smith & Wesson introduced the .38 S&W, a centerfire using a then-modern inside lubricated bullet. Powder-wise, it held about three grains less than the .38 Long. Here was another chance to fix the caliber mistake, because true .38-caliber bullet diameter would mean a case diameter too large to fit in any other chamber. But no, bullet diameter shrunk to .359 inch; barrel bore to about .350 inch. Now we had a .35 caliber!

The .38 S&W came to dominate the “pocket pistol” market in both the U.S. and Europe. Colt was left with the old outside lubed .38 Long (sometimes called the .38 Colt Double Action) and its early double-action revolvers that had issues with reliability and parts breakage.

Then in 1889, for reasons known to absolutely no one, the U.S. Navy adopted a double-action Colt revolver chambered for the old .38 Long centerfire cartridge. Again, there was a chance to fix the caliber thing by creating a true .38-caliber round. But no, the old outside lubed cartridge remained, now called the .38 Colt Navy.

To make matters worse, the army also cashiered its Colt single-action revolver and cartridge. Officers said the old Colts’ “recoil was too great,” a “more modern” gun was needed and “other countries were doing the same thing!” Sound familiar? The sad part was that the army had tested – and its officers rejected – the finest combat handgun on the planet at the time, the .45 S&W Schofield. Why not just give the officers chrome-plated .22 rimfires to carry around and issue effective arms to the troops who needed them? It didn’t happen.

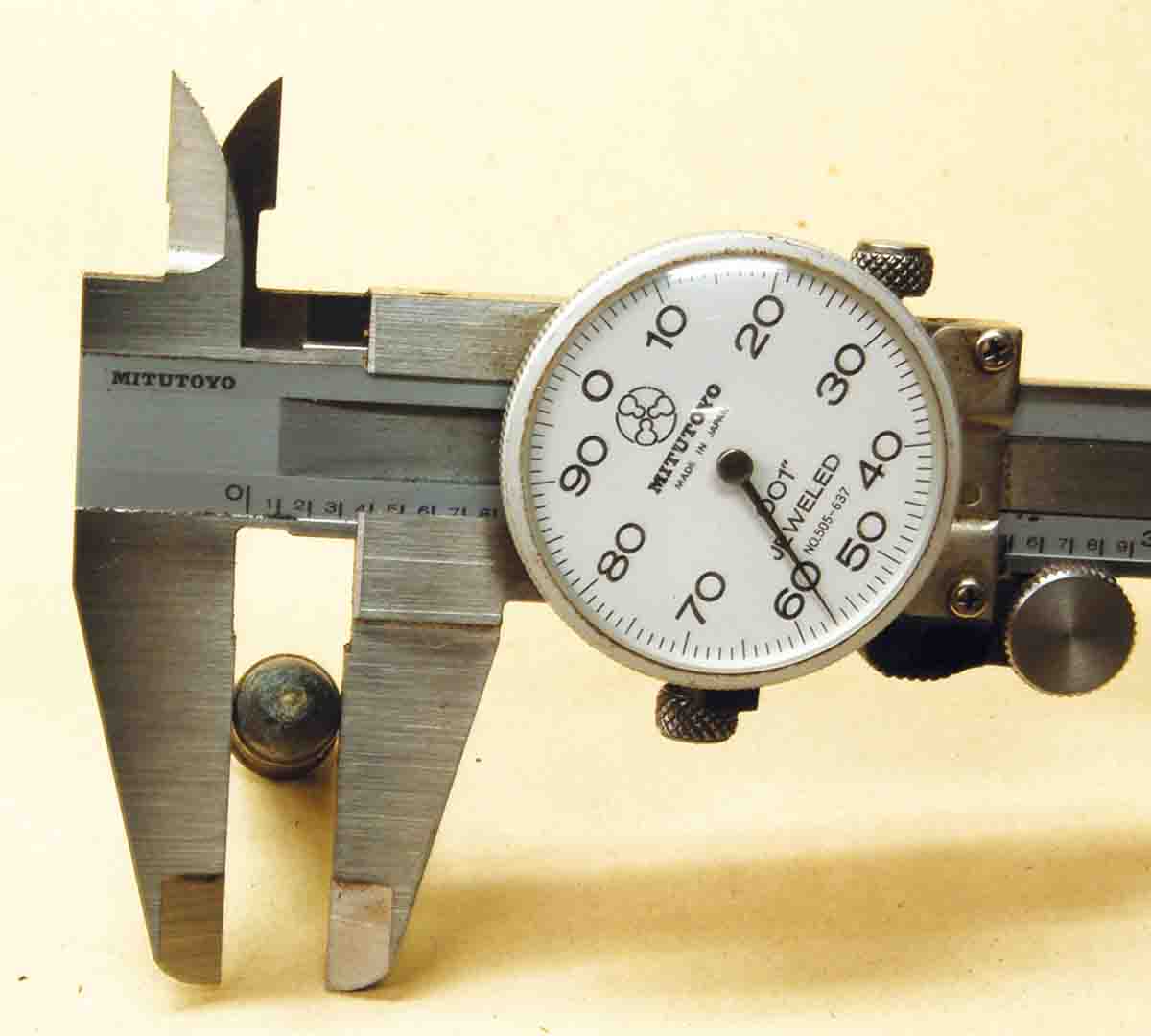

A Colt double-action revolver was adopted in 1892. Its cartridge was an inside lubed version of the .38 Colt Navy. Here was another chance to correct the caliber absurdity, but it was missed because the army round was also required to fire in the new navy revolver. U.S. Army specifications show a solid base (hollowbase was added in 1909) bullet having conventional square lube grooves. Diameter was .353 inch, though some references show .357 inch. How could accuracy possibly be acceptable from the navy revolver’s .378-inch groove barrel? Could black powder deform the bullet enough to seal the bore?

The bullet for the new army round was a 148-grain roundnose ahead of 15.4 grains black powder, resulting in about 750 feet per second (fps). Apparently, the round produced sufficient smoke, fire and noise to make the proper people happy. Reality would set in later.

The Army’s cartridge was mainly called the .38 Colt Army or .38 Army Double Action. Black-powder military loadings were issued for many years even though smokeless powder usage began in 1900. The powder was DuPont Bullseye in 3-grain charges. The bullet remained 148 grains. Velocity increased to 775 plus/minus 25 fps at the muzzle. Today, this is a .38 Special target load.

Hints that the new cartridge was inadequate for military use came in, but were ignored. Then, the Philippine Islands were ceded to the U.S. in the treaty that ended the Spanish-American War. Some Philippine residents didn’t like this much.

On certain islands, the people were Muslims (then called Moros). They considered it their duty to kill anyone who disagreed with them. The army was sent to stop the violence. Moro ambushes in thick jungle resulted in hand-to-hand fighting where they could absorb four, five, even six bullets from the .38 revolver and still fight its owner to death. The army troops demanded effective handguns and shotguns! This situation is covered in my column in Handloader No. 260 (June-July 2009).

The army’s handgun problem was eventually solved by issuance of the Colt M1911 and its .45 ACP cartridge. Yet, the .38 Army round didn’t quickly disappear because so many of the old revolvers had been chambered for it. The name, however, was generally changed to simply .38 Long Colt. The introduction of the .38 S&W Special (just a .38 Long Colt about .125 inch) in 1899 gradually caused the Colt round to become obsolete. Ammunition sales by Remington continued until 1977 and Winchester didn’t drop the round until 1985. The bullet in both makes was a 150-grain lead roundnose providing 730 fps for 175 foot-pounds of muzzle energy. That’s just under figures produced by the .380 Auto.

Anyone who owns one of the old Colts in working order today and wants to shoot it a bit will find producing handloads quite easy. World-famous cartridge case maker Starline (starlinebrass.com) sells properly headstamped brass. Dies are available and any 150-grain lead roundnose bullet of so-called .38 caliber will do fine. Duplicating the Winchester and Remington factory loads is the goal – nothing hotter in the old revolvers.

Having said all this, imagine for a moment if S&W had designed a real .38 caliber in the .38 Special. Its larger bullet would have made the round more powerful using black powder and given great possibilities as smokeless powder was developed. Then there is the .357 Magnum, which would have been the .388 Magnum. A heavier, .030-inch larger diameter bullet would have given enough power to make the .41 Magnum unnecessary. Revolvers could then… oh well, such is the strange world of cartridge history.

.jpg)