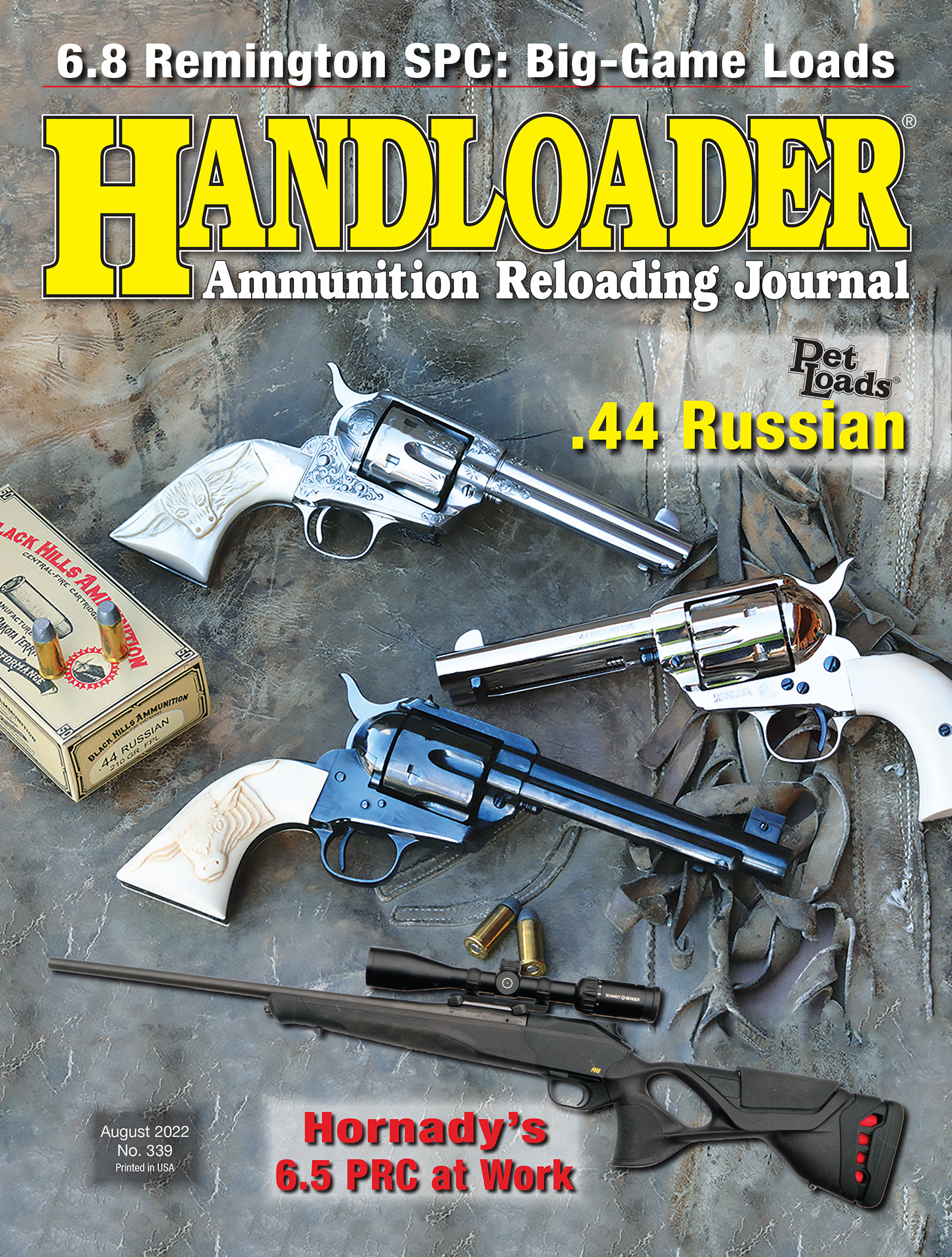

A Duo of Colt Frontier Six Shooters

Testing New Loads

feature By: Mike Venturino - Photos by Yvonne Venturino | August, 22

Early in 2021, a longtime quest of mine was fulfilled. That was a search for a fine condition, smokeless era, 1st Generation Colt Frontier Six Shooter with a 7½-inch barrel. For the unknowing, Colt Frontier Six Shooter in one version or another is how the manufacturer stamped “most” of its .44-40 Single Action Army revolvers between 1877 to 1941 when production ceased the first time. Early on, Colt acid etched “Colt Frontier Six Shooter” in small panels on the barrels’ left sides. Later, the marking was roll-stamped in several versions, with my new one dating from 1913 being marked “Colt Frontier Six Shooter.”

Also, it should be recognized that in 1877, the cartridge commonly known today as the .44-40 was then the .44 Winchester Centerfire (WCF) because it had been introduced in Winchester’s levergun Model of 1873. The double-digit designation of .44 for caliber and 40 for factory loaded grains of black powder probably first occurred with Marlin’s leverguns in the late 1880s and eventually became the round’s official name.

With Colt’s SAA reintroduction in 1976 after a two-year hiatus for retooling, the first 3rd Generation calibers offered were .45 Colt and .357 Magnum. Popular demand caused the .44 Special’s addition in 1978. In 1982, at the NRA Convention in Philadelphia, Colt’s news was that .44-40s were again available. I ordered one right there. A dozen more 3rd Generation .44-40s have passed through my hands in the nearly 40 years since that first one. Only three have stuck; two with 4¾-inch barrels and one with a 3-inch barrel. All have auxiliary .44 Special cylinders, and the shorter one gets used most with its special cylinder and shot loads for dispatching rattlesnakes around my property.

One day in the mid-1970s, a Montana friend approached with his father’s Colt SAA, asking if I had a few rounds of .44-40. His revolver’s serial number dated it as an 1882 production, but strangely, it had no caliber mark at all, nor the CFSS panel. I said, “How do you know it’s a .44-40?” His reply was, “Because Dad said it was, because .45 Colt’s wouldn’t go in and because I shot a few factory .44-40s in it.” So I loaded him a handful of .44-40s or at least tried to. In my inexperience, they carried a mild charge of smokeless powder, which I would never do now for such an old SAA. Bullet sizing diameter was .427 inch as was listed as nominal from several sources. Not one of those rounds would chamber. However, full-length sized cases fell into all chambers. Some research revealed that early .44-40 lead bullet factory loads contained .425-inch bullets, and modern jacketed bullet factory loads still use .426-inch bullets. A Lyman .425-inch lube/sizing die was ordered and the subsequent handloads chambered and fired perfectly. (Or at least they didn’t damage that old black-powder era Colt.)

At that point, I considered myself an old hand at .44-40 reloading, so at the very first Montana gun show attended in 1977, I hunted up a CFSS for myself. It was truly nice; fully nickel-plated, 4¾ inch barrel, black checkered, hard rubber grips and the magic “Colt Frontier Six Shooter” roll marked on the barrel. Made in 1892, it was a black-powder era Colt and still in my ignorance handloads for it again carried smokeless powders. This time, from the beginning, rounds loaded with .425-inch bullets fell right in the chambers, but to my puzzlement, accuracy was pathetic. Groups ran 4 to 6 inches at 25 yards. Slugging of barrel and chambers revealed the problem. By this time, Colt’s .44-40 barrels were nominally .426/.427 inch, but my cylinder’s chambers wouldn’t accept rounds loaded with bullets larger than .425 inch. Since those bullets were hard cast and powder charges (hence pressures) mild, bullets did not obturate to grip rifling. In other words, they were just wobbling through the barrel and landing hither and yon. Selling that handsome CFSS to a non-shooting collector wasn’t a problem.

Here follows the barrel/chamber dimensions of my CFSS duo with 7½-inch barrels. The 1913 one has all six chambers at .426 inch and barrel groove diameter also at .426 inch. To be perfectly honest, the .426 plug gauge is the tiniest bit loose in the chambers but a .427-inch gauge refuses to enter them at all. The CFSS from 2008 has four of its six chambers at .429 inch and two at .428 inch. Barrel groove measurement is .427 inch. Also checked were barrel-cylinder gaps. The 1913 gun is .006 inch. The 2008 gun is .005 inch.

Let’s first consider the array of .44-40 handloads chronographed through my CFSSs over a period of months. In this component shortage situation we are now experiencing, I did have suitable primers and powders on hand but nary a commercial cast bullet or any factory loads. Therefore, all bullets used herein were cast by me of 1:20 tin-to-lead alloy. Three designs were RN/FPs designed specifically for .44-40. Those were Lyman’s 427666, and two from RCBS: 44-200-CM and 44-200-FN. All three of those .44-40 designs are rated at 200 grains. Their actual weights from my moulds and alloy are listed in the load table. The fourth bullet is intended for .44 Special and is a copy of the Lyman 429478 mould, a 200-grain RN. They were cast in a four-cavity custom mould made for me by Dave Farmer at Hoch Moulds of Roswell, New Mexico. This latter bullet wouldn’t be suitable for use in magazine tube-fed repeating rifles but serves well in revolvers. All bullets were sized to .428 inch and lubed with DGL.

A word here about DGL is worthwhile. It was developed specifically for black-powder cartridge shooting and I have been aware of it for years. However, a young Idaho couple who are active in BPCR Silhouette bought the business in 2020, so I gave it a try. It works very well as a lube for both smokeless and black-powder cartridge bullets. In firing several hundred rounds of cast bullets from my Colt CFSS duo, I removed not a speck of lead from either barrel.

My primary goal was to compare two Colt .44-40 revolvers made 95 years apart. Both revolvers were new to me and had never been test-fired for accuracy while in my care. In the time of component plentitude, ideally, I’d test-fire 12-shot groups from the Ransom Pistol Machine Rest. That meant two rounds fired from each chamber. With shortages, I reduced groups to five shots. Since 20 groups were fired from each CFSS, I could still gain some insight on bullet and powder performance in each revolver.

Group measurements were rounded off to the nearest eighth of an inch of the two widest shots, and when fractions were converted to decimals, they were again rounded to the nearest hundredth of an inch. Also, every shot fired was counted. Once with the 1913 CFSS, an errant flyer caused a nice, 1½-inch or so cluster to expand to a 3½-inch five-shot group.

In regard to powders, Vihtavuori’s Tin Star won top honors. Eight groups were fired with each powder and its average was only 1.68 inches. Again, that single flyer made trouble. It caused Trail Boss’s eight-group average to hit 1.99 inches. Actually, looking over the averages per powder and per bullet, none performed badly. By my standards, they were all acceptable, with some downright fine. The same goes for those two .44-40 revolvers crafted by Colt 95 years apart. The 1913 gun averaged 1.99 inch for 20 groups fired and the 2008 gun was only a bit better at 1.79 inches.

Many years ago, the late Col. Charles Askins wrote that he saw no need for the .44 S&W Special to have been developed because the .44-40 already existed. Although there is some logic there, I don’t go so far as agreeing with that assessment. That said, I do handload and shoot many more .44-40s than .44 Specials.

.jpg)