300 H&H Is No Pushover

But Barrel Length Is Important

feature By: Terry Wieland | August, 23

The Wimbledon win established the 300 H&H as superior to the 30-06 for long-range shooting, and the second made it readily available to the average rifle nut and big-game hunter. Unfortunately, as always happens with champions, it exposed the “Super 30,” as Holland’s initially dubbed its creation, to a legion of nitpickers and nay-sayers in the American sporting press. The nitpicking and nay-saying have continued to this day.

Admittedly, there are many 300s on the market today that deliver ballistics slightly to greatly superior: the 300 Winchester Magnum is the obvious one, but there is also the 300 Weatherby and the 300 Ultra Mag, and so many wildcats and lesser knowns that we’d run out of space before we ran out of names.

Conversely, though, there are just as many lesser 30s that continue to prosper, starting with the 30-06 Springfield and 308 Winchester, including the far-from-dead 30-30 Winchester and even the 30 Carbine. As anyone can see, there’s a vast range of performance in cartridges that take .308-inch diameter bullets. Each has its uses and each is suited to a particular type of rifle, and this is just as true of the Super 30 as it is of the 30-30 Winchester at one end and the 300 Weatherby at the other.

The case has a pronounced taper and a very long shoulder sloping to its neck – a shape that Ballistician Ken Waters likened to an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). Waters believed that this made it the most visually attractive of cartridges, which is a subjective judgment that means less than nothing to the average hunter or target shooter. But Waters had other reasons for his admiration, which we shall get to.

In England, big-game cartridges were powered by cordite, a type of smokeless powder extruded into long strands. The 300 H&H’s shape made it easy to load cordite, or so the story goes. More important, cordite is a hot-burning powder. Holland’s kept this in mind, along with the fact that its rifles and cartridges could be used everywhere from the sizzling plains of northern India, to the Kalahari Desert, to the Himalayan mountaintops.

Ease of feeding and, even more important, extraction, were major considerations. The Super 30s long, tapering form allows it to slide effortlessly from a box magazine and stuck cases are unknown. Since the case headspaces on its belt, the gradual shoulder presents no problem, real or theoretical, although one must be careful not to move the shoulder back with repeated reloads. But that gets us into a whole new area.

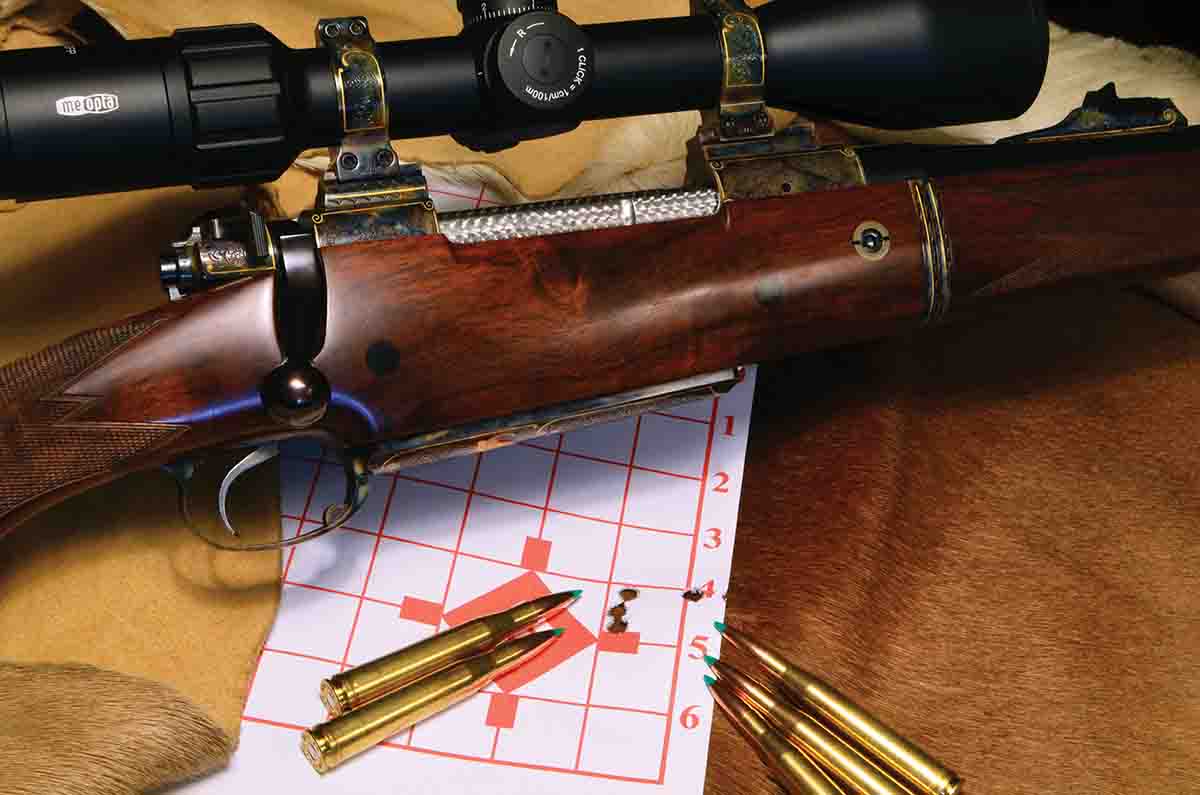

Inexplicably – to me, at least – he ordered a 24-inch barrel, the same as his Browning. Twenty-four inches was all you could get in the Browning High Power, but with the Holland he could have had 26 inches, or 28, for that matter. He never explained why, and this is puzzling because it had long since been proven that the 300 Magnums deliver the goods in 26 inches, but not 24. The Model 70 in its original form had a 26-inch barrel, and the accompanying table shows the difference in performance between the two lengths.

Jack O’Connor, the most respected rifle writer of his day, had scant regard for the 300 H&H. Like many others, he considered it a “loud, hard-kicking 30-06,” which is understandable if you are using heavy bullets and slow powders in a 24-inch barrel.

In The Hunting Rifle (1970), in his chapter on 300 Magnums, O’Connor told of buying a Model 70 in 300 H&H in 1950. Since he considered 26-inch barrels ungainly, he had it cut off to 23½ inches. This was the rifle that recorded the low velocity.

“To say I was dissatisfied by the performance would be an understatement,” he wrote. “About the only real differences I could see between the .300 H&H and the .30-06 when used in a barrel of the same length were that the .300 had more muzzle blast, and more recoil, used expensive ammunition, and had shorter barrel life.” That may well be true in a 23½-inch barrel but it certainly would not be if they were 26 inches. In that case, the 300 would display a significant advantage.

One could ask why O’Connor, who was a rifleman of vast experience even in 1950, would do that, but then one could also ask why Waters ordered a 24-inch barrel 30 years later.

We don’t know what bullets O’Connor was using, other than that they were 180 grains, and that can also make a difference. Or, how tight the chamber was on his 300 H&H.

What this minor controversy graphically illustrates is that you have to match the cartridge to the barrel length, the barrel to the rifle’s intended use, and the bullet(s) to both considerations.

Roughly speaking, the 308 Winchester bears the same relationship to the 30-06 as the latter does to the 300 H&H. The 308 is perfectly suited to its 1952 chambering in the original Model 70 Featherweight with a 22-inch barrel, ideally shooting bullets ranging from 130 to 165 grains. The 30-06 is best suited to a 24-inch barrel, shooting 150- to 180-grain bullets, and the 300 H&H to a 26-inch barrel and bullets from 165 to 200 grains. Certainly, you can go longer and shorter, lighter and heavier, in all three cases, but we are discussing what is best suited to what.

One reason for writing this article was to give the 300 H&H a chance to show what it could do with some of the newer powders, but here we run into the problem of published data. Because of its semi-obsolescent status, not every powder or bullet company is going to invest in a pressure barrel, and the time and money, to develop data for it. Shooters World, for example, has none whatsoever.

Other data, while it may exist, might include only powders that were available 30 or 40 years ago, some of which may not even be obtainable now. So, while we might like to be absolutely up-to-date with our loads, in some cases it’s simply not possible.

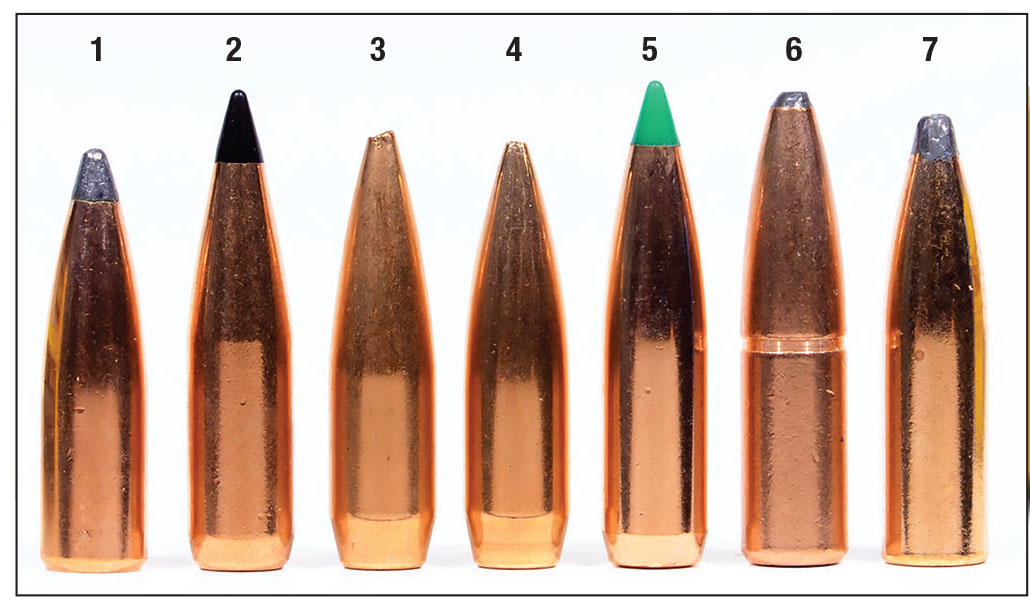

For this article, aside from the aforementioned problem load with 180-grain bullets, I chose to use only 165-, 168- and 200-grain bullets, which I consider the 300 H&H’s optimum weights for a wide range of game. I also tried to involve as many bullet and powdermakers as possible and use the newest data where it was available.

It’s interesting to note that most of the published data was developed with 24-inch barrels, but since for all the newest data these were special pressure barrels, with the tightest of tolerances, what they recorded and what you might get in your 1965-era Browning High Power, are two different things.

In the end, there are so many variables at play, all you can do is start at the bottom, develop some loads, chronograph them and then test for accuracy.

Because of Ben Comfort in 1935, I included two match bullets in the test, both 168 grains.

Hodgdon’s wonderful H-4350 got more exposure than any other powder because it comes so highly recommended for the 300 H&H from so many different sources, starting with Ken Waters and continuing with Nosler and several others. As the table shows, it lived up to its billing and would probably be my “one powder” if that ever came to pass.

H-4831 was omitted deliberately simply because so much data exists for it.

The Nosler Partition 165-grain at better than 3,100 fps in both rifles, along with its excellent accuracy, puts it solidly in the same class as the 180-grain Ballistic Tip.

Keep in mind, these are loads drawn from published data, not tailored to these rifles. I’d be willing to bet I could start with these and work up and down until I got much smaller groups.

I was hoping for better performance from a 200-grain bullet, but I was limited by what was logistically possible.

As mentioned, H-4350 did everything that was expected, and IMR-4350 was superb. Norma’s MRP was a disappointment, delivering low velocities, and Alliant’s RL-25 is, I believe, simply too slow for this case; either brand of 4350 is a better choice.

We are only a couple of years away from the 300 H&H’s 100th birthday and, contrary to all the reports of its demise, from 1960 onwards, it is still around. Rifles are still being chambered for it, factory ammunition is still being made, and first-rate brass is available from a number of sources. Also, in my opinion, it may well still be the best all-around choice in a 300 Magnum. Just be sure to get a 26-inch barrel.

.jpg)