The Ruger LCR in 357 Magnum is a fine example of a modern snub-nose revolver. A mix of steel and polymer, the little revolver carries easily and hits hard on both ends.

Several years ago, I was hired by the defense team of a man accused of homicide. The victim had been killed by a single gunshot wound to the head. The bullet had entered the victim’s eye near the tear duct, traveled through the brain and struck the occipital bone hard enough to cause a fracture but not exit the cranium. X-rays clearly showed the outline of a nearly pristine .357-caliber bullet resting between the occipital lobe and the cerebellum. Based on powder tattooing, a telltale sign of a close-range shot, the crime lab had placed the range at approximately 18 inches.

A foreign-made revolver with a 2-inch barrel had been found near the scene. It contained one fired casing and five loaded rounds in the cylinder. All of the cases were headstamped “357 Mag CBC” and displayed the distinctive “C”-stamped primers manufactured by CBC Global Ammunition. The cartridges were identical to a partially-filled box of Magtech factory ammunition found at the scene. The handgun was known to belong to the victim and was usually hidden in a location known to family members for self-defense.

Most testing was done in the late winter and early spring. Cold conditions made for long days at the range, but the view from the office was always fantastic.

A test bullet fired by the crime lab and compared to the one recovered from the victim indicated that the fatal bullet’s hallmarks were consistent with the revolver found near the scene. This is a step below an absolute match between a firearm and the recovered bullet. This level of match included the firearm as a possible source of the bullet based on the larger hallmarks left by the lands and grooves of the barrel.

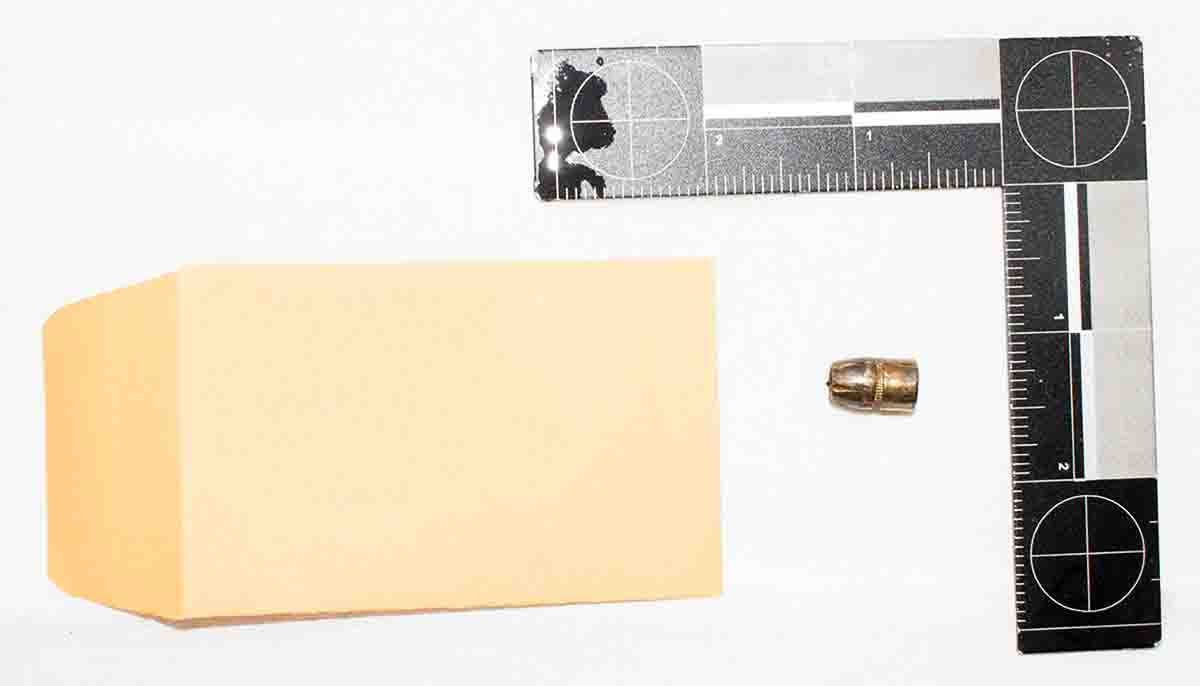

The recovered bullet matched the others found in the cylinder by manufacturer, weight and shape. It showed little deformation, which in combination with its apparent lack of performance led the defense team to a surprising conclusion.

The attorneys were concerned by an apparent lack of energy and penetration as evidenced by the bullet’s failure to exit the skull. They felt that a magnum-type cartridge should have done more damage. Based on his personal knowledge of the 357 Magnum cartridge and evidence provided by the autopsy, one of the lawyers had formed a theory of the case involving a government assassin. If you didn’t see that one coming, you’re in good company. I didn’t expect it either.

Based on personal knowledge garnered from a documentary, he told me that assassins often removed some of the powder from cartridges to limit the muzzle report. He believed that since the victim had been involved in covert activities during the Vietnam War, it was possible that a governmental agency had decided to have him eliminated. The defense team was hoping that I could prove or disprove that there was energy missing from the shot that had taken the victim’s life. Lawyers can be a squirrelly bunch.

The area around the entry wound exhibited greenish-yellow granules along with the expected darker spots typical of powder tattooing. These granules were also present on the victim’s clothing. The lawyers were interested in these as well and had asked me to identify them if possible. The presence of these tiny particles offered a significant clue regarding the bullet’s apparent lack of energy.

A forensic examiner displays the five unfired cartridges and one fired case of the snub-nose revolver found near the homicide scene. Later ballistic comparisons would find that the bullet taken from the victim was consistent with this firearm.

Under ideal circumstances, smokeless powder will burn almost completely while under pressure and in close proximity to other burning-powder grains. In ballistics, this process is called propagation. Slower-burning magnum pistol powders take longer to reach peak pressure in comparison to faster powders and also maintain peak pressures for a longer span of time. This is why magnum handgun charge masses can be so large and still operate at moderate pressures. These larger charges create more propellant gas, which is available to effectively accelerate a bullet over a longer period of time. If the firearm is unable to provide a pressurized environment long enough for the powder to propagate effectively, declines in velocity are a natural result.

When a double-base powder fails to ignite, often only the deterrent layer (the portion of the powder molecule that controls its burn rate) is burned off. The energetic component of the powder fails to ignite and instead is forced out of the barrel along with the bullet. These unburned molecules often exhibit a distinctive color pattern that runs from golden to greenish yellow. The presence of these molecules is a sign of inefficiently burning powder.

I purchased a box of Magtech 357 Magnum ammunition and was disappointed, but not surprised to find that it was from a different production lot. Since ammunition from the crime scene was not available to the defense for testing, this other lot was the best option available. I pulled a handful apart and weighed them to find the average charge mass. A comparison of the known charges of powder to loading data indicated that the propellant was probably an Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) variant of Winchester 296.

These golden granules found on the victim’s body were of great interest to the defense team. The presence of these unburned grains of propellant provided insights into the lack of penetration shown in the autopsy report.

The obvious step next was to test a 357 Magnum snub nose over a chronograph and measure the results. The main problem with this idea is that the court system is not the real world. I was concerned that the prosecution would simply point out that the test revolver was not the one found at the scene, rendering any test data flawed. I will also admit that I expected one of the lawyers on our team to use this point to protect his alternative theory of the crime.

Instead, I used an internal ballistics program designed to predict pressure and velocity. Based on the charges used in the Magtech rounds, it became evident that performance dropped dramatically when a 2-inch barrel was used. The slower burning magnum pistol powders used to give the 357 Magnum its impressive muzzle velocities and energies in longer-barreled firearms simply did not propagate as well in very short barrels. Faced with my report, the defense attorney was forced to drop his theory of the case and move to a more conventional defense of his client.

With a 1.87-inch barrel, the LCR necessarily has a short sight radius, but the sights were well regulated. At the ranges the revolver was designed for, they are more than adequate.

Flash-forward a handful of years and now I find myself the happy owner of two Ruger LCR revolvers one in 38 Special and another in 357 Magnum. They are lightweight, carry easily and boast very nice double- action-only triggers. The little 357 seemed a good companion for flyfishing trips here in Idaho, which has a liberal helping of wild things that bite. Now armed with a 1.87-inch barreled LCR and with no lawyers to interfere, I decided to see what snub-nose 357 Magnums do in the real world.

I am a strong proponent of factory ammunition when it comes to self-defense, but I am more likely to be carrying the little Ruger while hiking or fishing. My goal was to find a load that operated with enough velocity to justify the Ruger’s recoil and muzzle flash. I wanted it to be a magnum. As a control, I tested a 4-inch Ruger Security Six to compare velocity shifts.

All of the factory loads I tested performed better than I had expected. All three of the 158-grain loads exceeded 1,000 feet per second (fps) from the little Ruger with an average energy of 384 foot-pounds. The 4-inch Security Six produced only about 10 percent more velocity delivering an average of 1,143 fps.

Compact as it is, the LCR is approximately the same size as the 10-shot Glock 26. In testing, 9mm Luger loads from the Glock compared well against the short-barreled 357 Magnum.

Three lighter factory rounds were also tested. Remington’s 125-grain JSP at a published velocity of 1,450 fps is typical of the performance expected from 357 Magnum cartridges. Hornady’s Critical Duty 135-grain loads at a published 1,275 fps represented a good compromise between bullet weight and velocity. The FTX bullet design has a good reputation for consistent expansion at lower velocities and seemed a good match for the LCR. Finally, in the mix were Federal Personal Defense 38 Special +P using 120-grain Punch bullets. The results were interesting.

This group, far and away was the best one shot in testing, was the product of 158-grain Speer Gold Dot bullets and Ramshot True Blue. This load combination proved the most accurate in the LCR.

Using 38 Special +P ammunition in a 357 Magnum is a common approach to mitigating recoil in smaller revolvers. I’ve heard it said that the 38 Special +P doesn’t give up much to the 357 Magnum when fired from snub barrels. It actually gave up quite a lot. The 357 Magnum LCR averaged 915 fps and compared rather favorably to the Security Six that averaged just 47 fps faster. Fired through my 38 Special LCR, the Punch bullets averaged 931 fps.

The 357 Magnum Remington 125-grain JSP loads averaged 1,208 fps from the short-barreled Ruger and 1,329 fps from the Security Six. Hornady’s heavier 135-grain bullet was very consistent throughout testing and produced an average of 1,200 fps. There is a definite ballistic advantage to magnum loads in the little Ruger, but it came at the cost of increased recoil and muzzle blast.

Factory ammunition shot well in the LCR producing both reasonable accuracy and velocity. This group, made by Hornady Critical Duty 135-grain loads, was fairly typical of the accuracy of the factory loadings.

When I moved on to handload testing, recoil and muzzle blast became my constant companions. After the first day of range testing, I came home feeling like I had lost a giant pillow fight hosted by professional football players. The little Ruger is quite light, tipping the scales at 17.1 ounces empty. Even with the well-designed Hogue Tamer grips, recoil is noticeable.

This is a very accurate revolver for its type, but the amount of punishment it dealt out eventually impacted my ability to shoot it well. I ruined a lot of groups with fliers that can only be explained as shooter induced. My plan had been to develop loads at 9 yards, the closest testing position at our range, and then develop the most promising ones for testing at 25 yards. I discontinued that plan on the second day of shooting. I’m sure other shooters could make this little magnum shoot like a target pistol, but for me it is going to have to remain a short-range defensive tool.

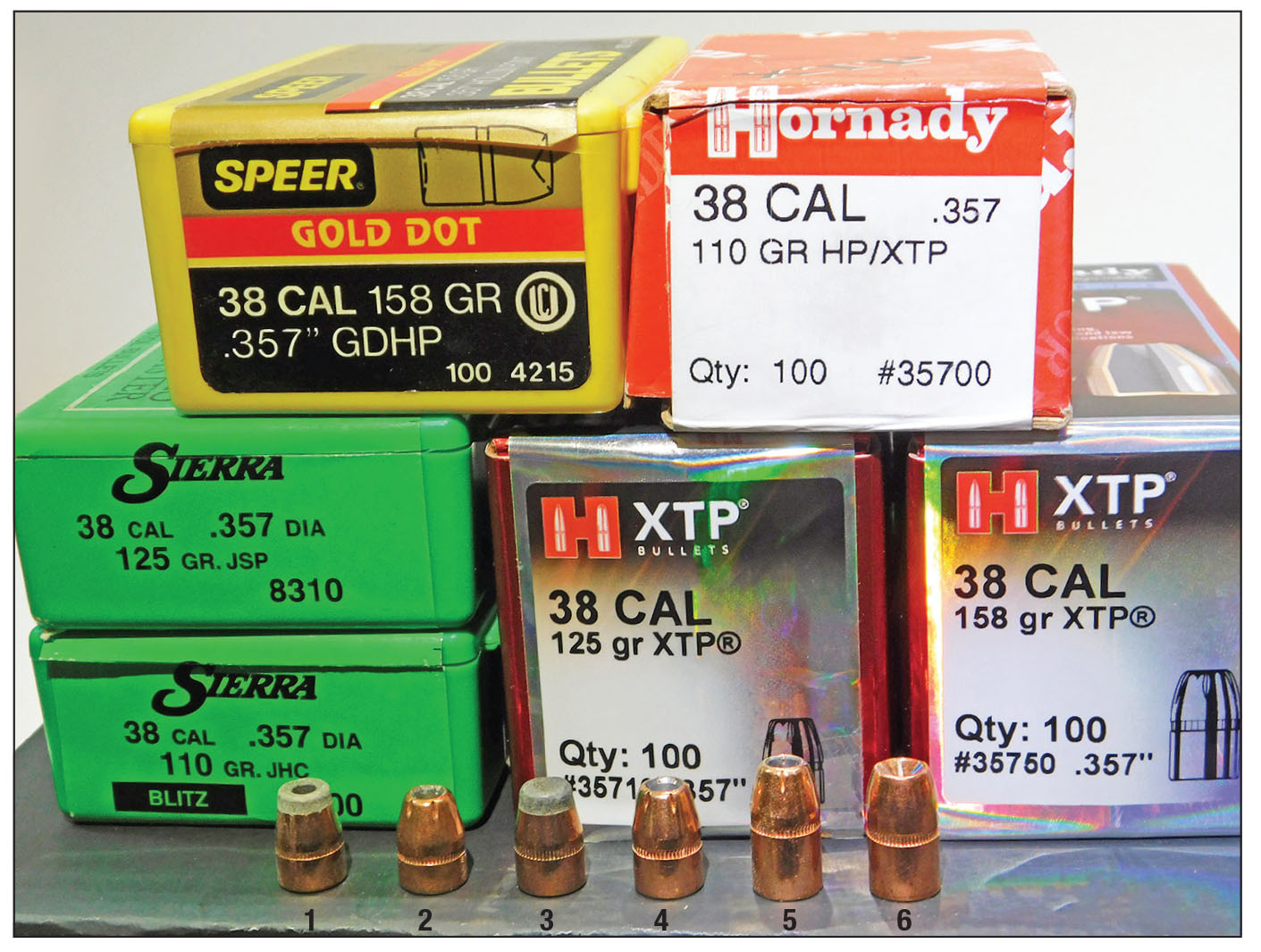

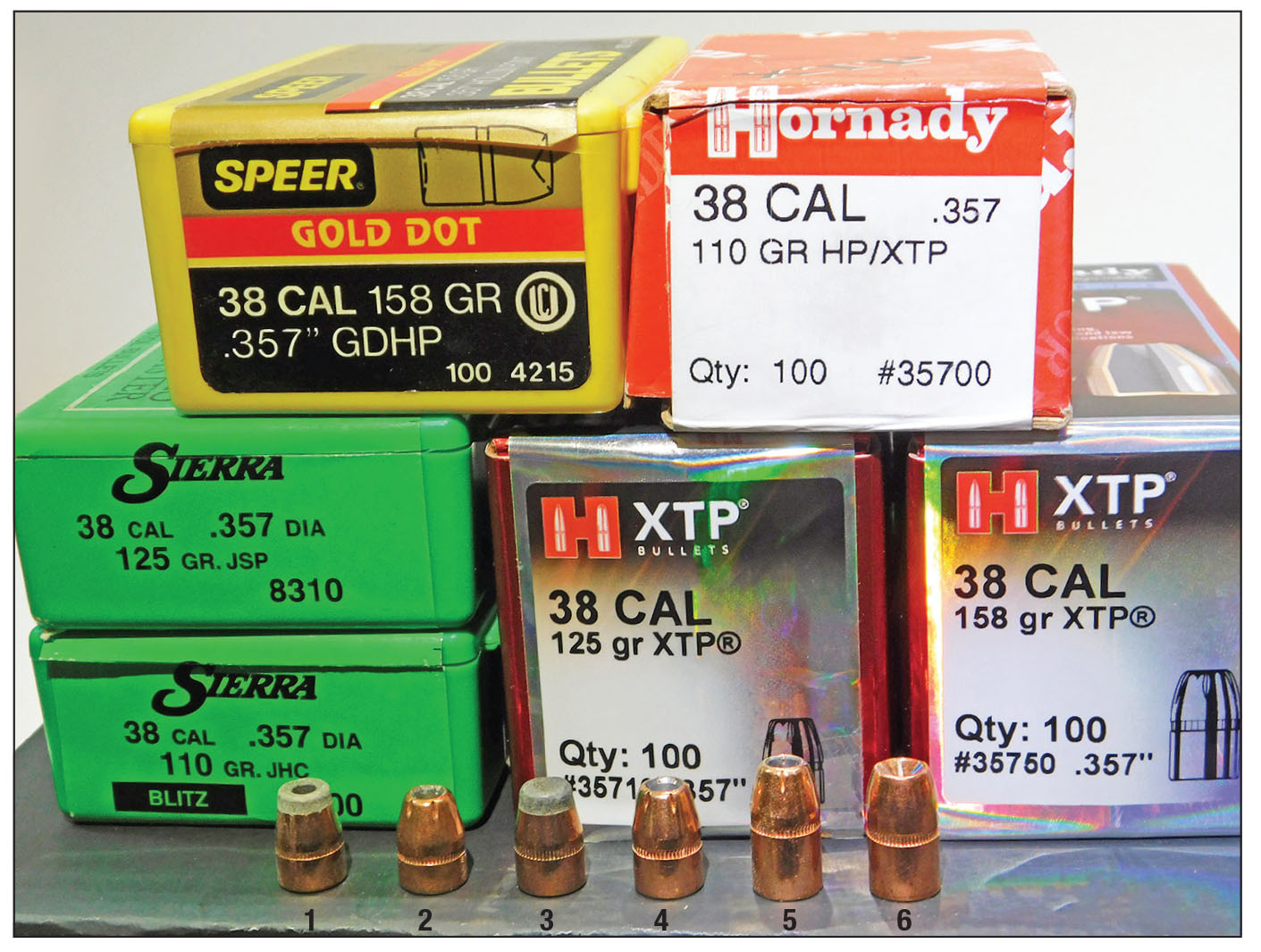

These six .357-caliber bullets were tested for performance in the LCR: (1) Sierra 110-grain JHC, (2) Hornady 110-grain HP/XTP, (3) Sierra 125-grain JSP, (4) Hornady 125-grain XTP, (5) Hornady 158-grain XTP and (6) Speer 158-grain GDHP.

When I set out to look at 357 Magnum performance in short barrels, I was looking for two things. I wanted to see if my research in that homicide case would be reflected in real-world shooting. I also wanted to have 357 Magnum-type performance that I could carry in my back pocket or fly-fishing vest. What I found was a middle position, which is often the answer in the tricky world of ballistics.

Exterior ballistics on the LCR put it in a class above 38 Special snub-nose revolvers if only velocity and energy are considered. The 38 Special +P at a Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) maximum of 20,000 psi simply did not have enough pressure to compete with the 357 Magnum. Performance in short-barrel revolvers comes down to a combination of powder burn rate and pressure. There is another short-barrel contender out there to consider.

Six factory loads were tested in the LCR. The 38 Special +P ammunition was included in testing because it is commonly chosen to help mitigate recoil in smaller 357 Magnums. The loads were very easy to control but lacked performance when compared to 357 Magnum loads.

The 9mm Luger and the 357 Magnum have the same SAAMI pressure specifications. Both are set to a pressure limit of 35,000 psi. The 357 Magnum is able to exceed the 9mm Luger’s velocity because its case capacity allows for larger charges of slower-burning magnum pistol powder. It is notable that the LCR using smaller charges of faster powders often matched or exceeded the velocities of much larger charges of slower powder. These trends were usually reversed when the 4-inch Security Six was shot for comparison. Larger charges of slower powder often contributed to notable increases in velocity. When the Security Six was fired using smaller charges of fast powders, there was a velocity increase over the LCR, but it was much less marked.

Handloads using these faster-burning powders were used to test performance in the short-barreled LCR. These powders often outperformed much larger charges of slower-burning propellants.

Comparing the LCR to a subcompact 9mm Luger is an interesting exercise. It’s an article of faith that the 357 Magnum is powerful and the 9mm Luger is relatively anemic. In this instance, the 9mm stands up rather well to the 357 Magnum. Physically, a Glock 26 is similar in size to an LCR. Ballistically, SIG Sauer 124-grain V-Crown ammunition averaged 1,197 fps out of the Glock’s 3.43-inch barrel. Compared to factory Remington 125-grain JSP loads in the LCR, the little baby gave up .002 inch in diameter, 1 grain of weight and 11 fps.

If I carry the LCR as a defensive pistol, it will be loaded with Hornady Critical Duty 135-grain ammunition. That load is capable of bringing magnum-type performance to the LCR. More likely, it will be loaded with a combination of snake shot and 158-grain Gold Dots pushed by a stout charge of Ramshot True Blue for outdoor adventuring. Finally, this testing tended to validate what I told those lawyers all those years ago. It was simple internal ballistics rather than a shadowy assassin.

These slower-burning powders are all top performers with 357 Magnum loads in longer- barreled firearms. When fired from the little Ruger’s shorter barrel, some came up lacking in performance.

.jpg)

.jpg)