.41 Magnum (Pet Loads)

A Multi-Purpose Sixgun Cartridge

feature By: Brian Pearce | February, 20

At the 1963 NRA Annual Meetings Elmer Keith and Bill Jordan met with representatives from Remington, Smith & Wesson and Ruger to obtain commitments for them to work together to develop a new sixgun cartridge. Specifically, it would be a “.40 caliber…that would push a 200-grain bullet at around 1200 fps.” (This is identical performance to the original 10mm Auto as loaded by Norma in 1983.) The new cartridge was intended to fill the performance gap between the .357 and .44 Magnums. It would offer notably less recoil and muzzle blast than the .44 Magnum, which many shooters have difficulty mastering but it would still offer a large enough caliber and bullet weight to provide reliable performance for personal defense and law enforcement applications.

I knew Bill Jordan well and talked with him at length about the .41 Magnum in 1984. His idea was to have Smith & Wesson offer a “medium” frame revolver designed specifically for the .40-caliber cartridge. (The Smith & Wesson L-frame was developed in 1980, some 17 years after the .41 Magnum.) To permit fast follow-up shots, Jordan did not want more than 1,200 fps from the new cartridge. Jordan was responsible in convincing Smith & Wesson to produce a K-Frame .357 Magnum Combat Magnum that later became known as the Model 19. His law enforcement experience and fast draw feats on national television using live ammunition while hitting small targets all dictated a lighter gun.

Origins of .40-caliber revolver cartridges began with the Winchester Model 1873 rifle, first chambered during the middle 1870s for the .38 W.C.F., or .38-40 Winchester. For some unknown reason it was deemed a .38 caliber but actually utilized .400- to 401-inch bullets while the “40” indicated the black powder charge. Colt soon began offering the Single Action Army revolver in .38-40 (and later the New Service) then developed the .41 Long Colt (.41 Colt) in 1877 for the double action Thunderer and SAA revolvers.

The later cartridge had a rather limited powder capacity and performance capabilities. However, when the .38-40 was chambered in modern smokeless era SAA revolvers, it could take notably heavier loads for enhanced performance. The problem was that the comparatively thin bottlenecked case did not offer great strength and often split after just one or two reloadings, and the short neck limited bullet length and selection.

By 1932, Colt’s famous shooter J.H. “Fitz” Fitzgerald became aware of the cartridge and Colt contacted Remington for a special run of .41 Special ammunition with a 1.260-inch case length that would push a 210-grain bullet at 900 fps while a heavier loading would achieve 1,150 fps. (This original .41 Special cartridge should not be confused with the modern .41 Special that consists of a .41 Magnum case cut to 1.16 inches and is available from Starline.) For some unknown reason, Colt hesitated with the project, which was a mistake, as Smith & Wesson announced the .357 Magnum in 1935 and it remains a top-selling cartridge.

Colt responded by beginning development of a heavy .44-caliber load in its Single Action Army that would have essentially been a magnum to greatly overshadow the .357. That project was scraped when World War II erupted, and Smith & Wesson again beat Colt to the finish line with the .44 Magnum, but I digress.

The next notable .40-caliber experimenter was Gordon Boser. He too was fond of the many virtues of the Colt SAA and made lock work design changes in an attempt to increase its durability. The same as Eimer, Boser used the .401 Winchester case cut to 1.218 inches. He used 180-grain .38-40 jacketed bullets and 200-grain cast bullets of his design and called this wildcat the .401 Special. Boser had the advantage of the newly developed Hercules (now Alliant) 2400 powder developed in 1932 and resulted in notable velocity increases over previous wildcats.

Another notable .40 caliber was the .401 Herter’s Power Mag first offered around 1961 in a J.P Sauer single-action revolver. The cartridge was capable of pushing 180-grain jacketed bullets from 800 to over 1,400 fps, or 200-grain cast bullet at 1,300 fps. However, the gun had dimensional issues that limited accuracy, and neither was it an ideal service revolver. For several reasons, including the Gun Control Act of 1968, it became obsolete.

Elmer Keith was fully aware of Eimer’s and Boser’s .40-caliber wildcats but really wanted a heavy .44 Special load. Keith was pleased with the development of the .44 Magnum in 1955, after which he became an advocate of a lighter big-bore sixgun load that would duplicate Boser’s .401 Special with a 200-grain bullet at 1,200 fps for police use and would fill the gap between the .357 and .44 Magnums.

When Remington engineers began designing the specified .40-caliber cartridge, they immediately chose to increase caliber to .410 inch (groove and bullet diameter) to prevent the new round from chambering in .41 Long Colt revolvers that featured chambers that were bored straight through to accommodate both heeled and inside lubricated bullets with a hollow base. As a result, the case was not based on any previous case. Rather than choosing a “special” case length of 1.16 inches (approximately same as the .38 and .44 Specials), which would have had enough powder capacity to push a 200-grain bullet at 1,200 fps as requested by Keith and Jordan (and Skeeter Skelton), engineers chose a maximum case length of 1.290 inches, which is actually .005 inch longer than the .44 Magnum. Maximum average pressure was established at 43,500 CUP (same as the .44 Magnum), but today it has been changed to 36,000 psi.

This all resulted in the new .41 Magnum being housed in large frame revolvers. For example, the Smith & Wesson Models 57 and 58 were built on the N-Frame, which were externally the same as the Model 29 .44 Magnum but were actually heavier due to the .41’s smaller caliber. Ruger introduced the Blackhawk .41 Magnum that was likewise built on its large .44 Magnum cylinder frame. However, Ruger fluted and shortened the cylinder and used an aluminum XR3-RED grip frame to keep weight down.

Revolvers and ammunition began shipping in 1964. Initially, two Remington factory loads were offered that included a full-power version advertised to push a 210-grain soft point bullet at 1,500 fps and a 210-grain lead SWC (hollow base) at 1,050 fps from an 83⁄8-inch barrel, but real world velocities usually ran around 1,350 fps and 950 fps, respectively, from 6-inch barrels. The lighter load was intended for police use while the heavier load was for hunting or occasions when full power was beneficial.

Although some police agencies adopted the Smith & Wesson Model 58 Military & Police revolver, as indicated, it was heavy and the average officer found favor with lighter guns. In spite of being in the shadow of the .44 Magnum, it has gained acceptance among hunters. The difference in power between the two is not great. However, the .41’s recoil is notably less and many people shoot it more accurately. Back in the heyday of International Handgun Metallic Silhouette competition, the .41 Magnum earned notable respect due to its outstanding accuracy and enough power to reliably topple heavy steel ram targets at 200 meters.

I am fond of the .41 Magnum and have a good selection of Smith & Wesson and Ruger sixguns along with custom Colt SAAs and USFA guns and even a Marlin Model 1894FG. I have taken a considerable number of big game and small game with various .41 Magnum sixguns and consider it an excellent field cartridge. While it is relatively easy to duplicate and even exceed factory load performance with 210-grain jacketed bullets, its versatility can be notably improved through handloading. It performs well with heavy-for-caliber cast bullets (typically around 1,200 fps) that are suitable for deer, elk, black bear, etc., or it can push 215- to 225-grain cast bullets at a leisurely 800 to 900 fps with modest recoil and excellent accuracy.

Most .41 Magnum sixguns feature a .410- to .411-inch throat diameter while groove diameter is usually .410 inch. Commercial jacketed and monolithic bullets from Hornady, Nosler, Speer, Barnes, Cutting Edge and Sierra measure .410 inch while cast bullets are normally sized to .411 inch. This combination results in minimal bullet tilting, minimal base obturation and little deformation as bullets pass through the throats and into the forcing cone before fully engaging the rifling. As a result, most .41 Magnum sixguns offer outstanding accuracy.

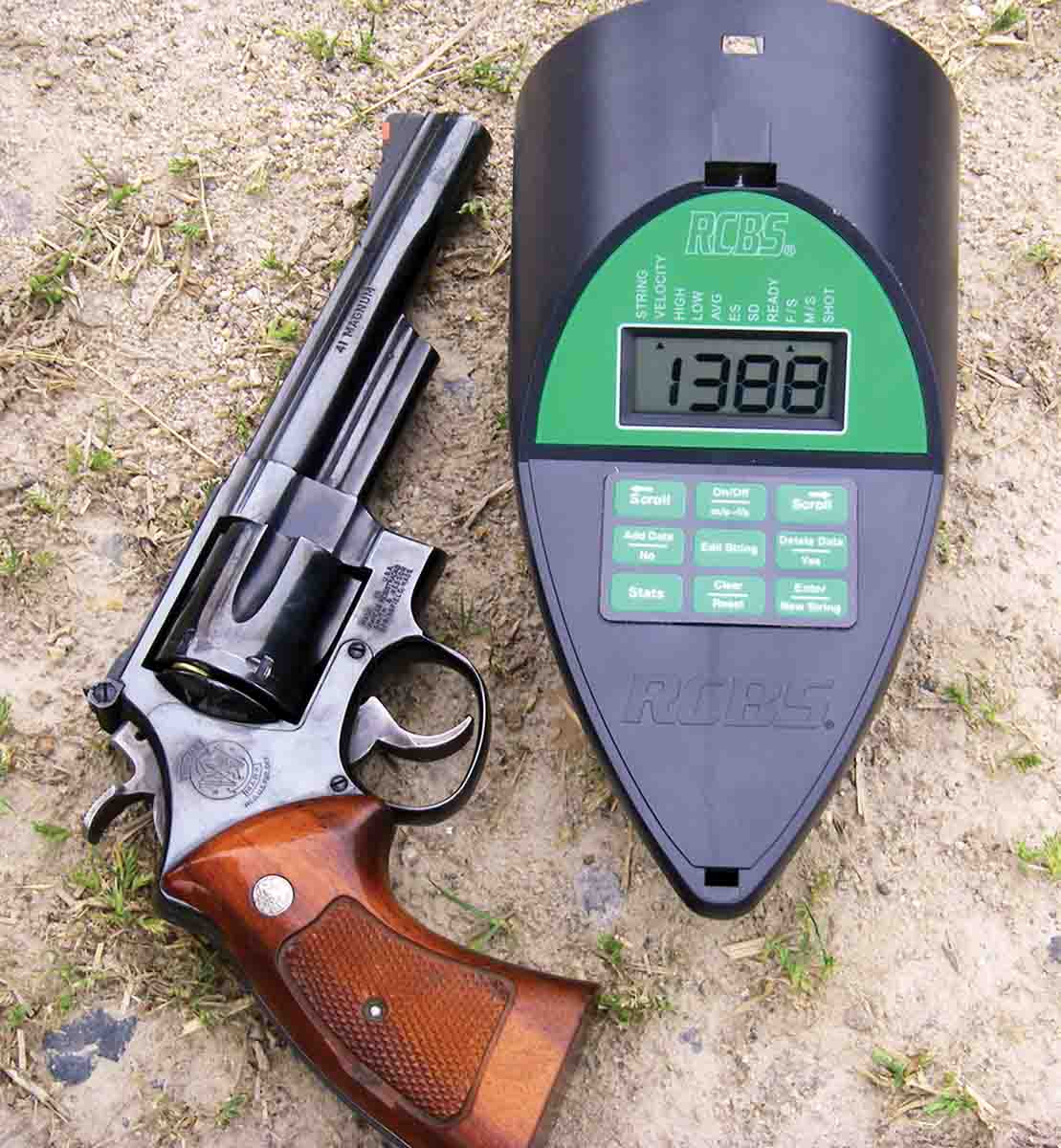

A Smith & Wesson Model 57-1 with a 6-inch barrel was selected to test the accompanying loads. I have had it for more than 30 years, and it has produced excellent accuracy with jacketed and cast bullets. The throats measure .410-plus while the groove diameter is .410 inch.

Industry maximum overall cartridge length is listed at 1.590 inches, and virtually all jacketed bullets feature a crimp cannelure that corresponds with that length. However, most U.S. made sixguns from Smith & Wesson, Ruger, Dan Wesson and the Freedom Arms Model 83 feature a long enough cylinder to accommodate longer cartridges, which becomes important when loading cast bullets that feature a nose length that exceeds industry specifications. Bullets so designed and seated out accordingly serve to increase powder capacity (and therefore velocity) but also position the bullet into the throat for better alignment with the bore. They also benefit from a shorter “jump” from the case to the rifling, all of which generally increases accuracy.

A few examples include the 221-grain Lyman/Keith mould 410459 seated at 1.695 inches, 223-grain Hensley & Gibbs Keith 258 at 1.698 inches, 226-grain Redding mould 410 at 1.674 inch and others. The Taurus Tracker and Freedom Arms Model 97 feature short cylinders and will require ammunition that is within SAAMI specification lengths.

With a straight wall case, the .41 can be used in conjunction with a carbide sizing die, with RCBS dies used to develop accompanying data. Full-length sizing is suggested to allow easy re-chambering. While bullets can be crimped during the seating process, I always suggest to first seat the bullet to the correct depth, then as a separate step apply a heavy roll crimp. This usually results in more uniform crimps, less bullet deformation and increased accuracy. For the accuracy-minded shooter, cases should be of one lot number and trimmed to a uniform length. Starline cases were used to develop the accompanying loads.

.jpg)

Most powders can be reliably ignited with standard large pistol primers, with CCI 300 primers used to develop most of the accompanying data. Some spherical powders, such as Hodgdon H-110, are better served in all temperatures with magnum primers such as the CCI 350. Accurate No. 11FS is a relatively new spherical powder that is flash suppressed and more or less duplicates the burn rate of H-110. While a CCI 300 primer was used with that powder, it might require a magnum primer for reliable ignition in cold temperatures.

Classic magnum revolver powders include Alliant 2400, Accurate No. 9 and Hodgdon H-110/Winchester 296. However, some newer propellants are worthy of consideration, such as Accurate No. 11FS, TCM, A-4100, Ramshot Enforcer, Alliant Power Pro 300-MP, Hodgdon Lil’ Gun and Shooters World Heavy Pistol. Some of the most accurate loads were obtained with powders offering more of a medium burn rate, including Hodgdon Longshot, CFE Pistol, Ramshot True Blue, Accurate No. 5, Alliant Power Pistol and Vihtavuori N-340. These powders often duplicate, or nearly duplicate, factory load velocities but produce notably lower extreme spreads, reduced muzzle report and good accuracy. For light target loads using standard weight cast bullets, Hodgdon Titegroup, Alliant Red Dot and Accurate No. 2 are excellent choices.

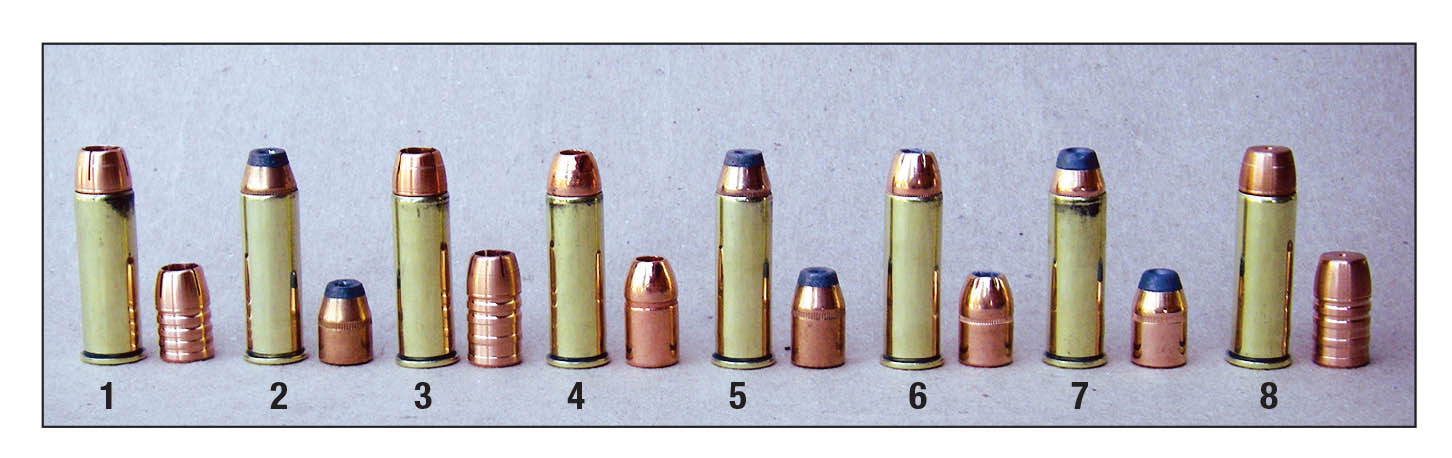

Bullet selection for the .41 Magnum includes popular 210-grain JHP bullets from Hornady, Nosler and Speer that offer reliable expansion at velocities above 900 fps and are good choices for general-purpose use and hunting deer-sized game. Cutting Edge offers its monolithic hollowpoint Raptor in 135- and 180-grain weights that gave an interesting blend of rapid expansion, deep penetration and outstanding accuracy with 25-yard groups often hovering between .5 and .75 inches. Cutting Edge also offers a 220-grain solid that is an excellent choice when hunting tough game such as bear, or when maximum penetration is needed, but it also gave one ragged hole accuracy.

Cast bullets and big-bore sixguns are a proven combination at velocities ranging from 800 to over 1,300 fps. For handloaders wanting to use the original Keith bullet, try the Hensley & Gibbs 258 (223-grains), which works well for light target to full house magnum loads. I have used this bullet on game and its performance is always reliable. For a heavyweight cast bullet, the 265-grain Oregon Trail WNFP GC (available under new ownership at oregontrailbullets.com) is a good choice that can be pushed to 1,300 fps with select powders.

Select loads were fired in a Marlin Model 1894FG with a 20-inch barrel. In its factory form this rifle feeds best with cartridges that are within the industry-specified 1.590 inch. With its relatively slow 1:38 rifling twist rate, the best accuracy was obtained with full power loads.

I have experimented extensively with the .41 Magnum. A few years back I had an experience that is worth sharing. While developing a number of handloads for a Smith & Wesson Model 57 with a 4-inch barrel, as powder charges were increased the velocity of the Hornady 210-grain XTP-HP bullet actually decreased by 20 to 30 fps with each half grain of powder increase. As maximum powder charges and pressures were reached, velocities jumped up to a more normal or expected figure. This was observed with Accurate No. 9 and Alliant 2400 powders. Knowing the oddity of my results, all loads were tested again and gave more or less identical results. While I have a theory of why this occurred, until I can prove it through additional testing, I will not state the reason. However, this occurrence is mentioned to illustrate the importance of load development and the value of a chronograph.

The .41 Magnum is an excellent cartridge. With more guns and factory loads available now than at any time in its history, it is clearly more popular than ever.

[For exclusive content on Elmer Keith’s Ruger Blackhawk .41 Magnum, visit handloadermagazine.com.]

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)