Everyman's Cartridge

Shooting the .308 Winchester/7.62 NATO

feature By: Mike Venturino | February, 20

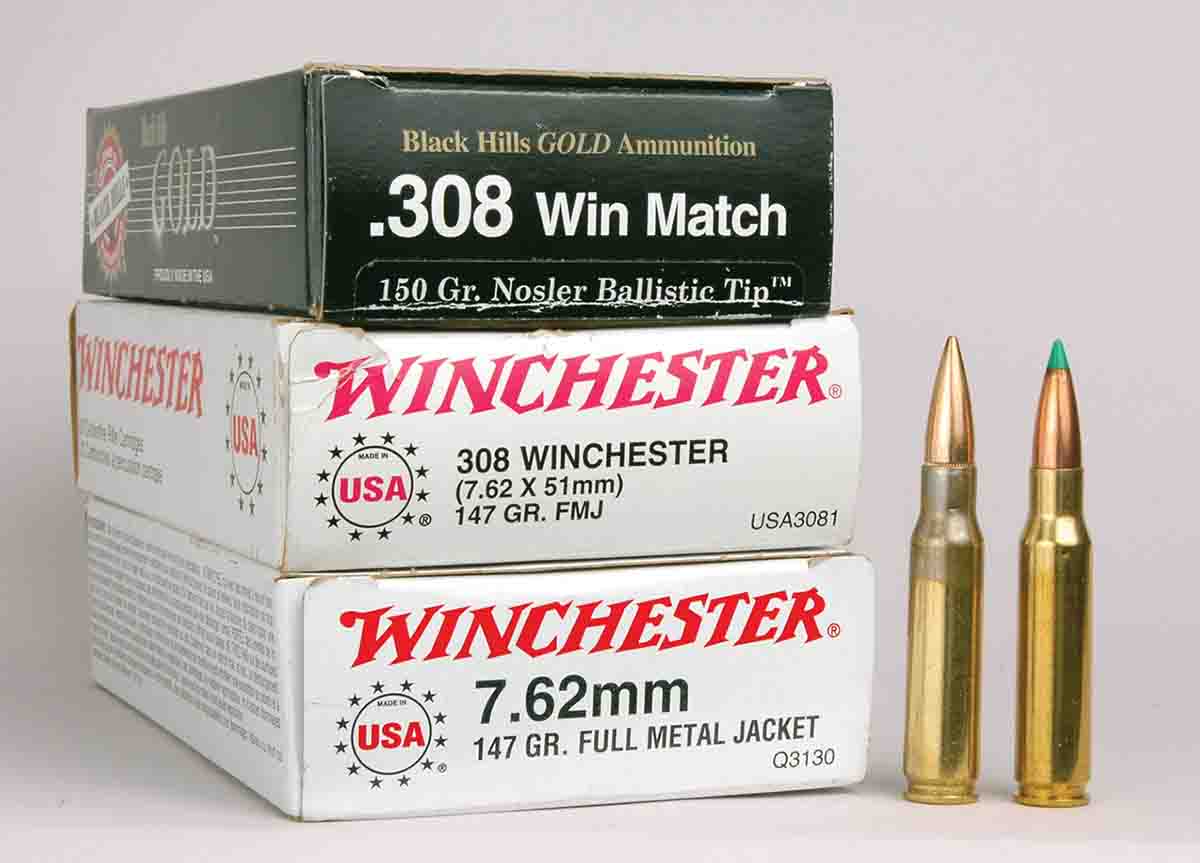

As readers undoubtedly know, the .308 Winchester was the civilian version of the U.S. Government’s 7.62x51mm NATO. However, it is less well known that Winchester beat the government by introducing its version in 1952. M14 7.62mm NATO rifles were not issued to troops until 1957. Dimensionally, the two rounds are the same and both will chamber in rifles labeled .308 Winchester or 7.62mm NATO. Whereas warnings abound that one should be careful in mixing .223 Remington and 5.56mm rifles and ammunition, I’ve looked for and not found warnings about the mixing the two types of civilian and military loads discussed here. In fact, as one of my photos shows, some ammunition boxes are labeled with both cartridges.

Another little known fact is that government testers actually started with the .300 Savage as their T65 (T meant experimental) and eventually, with several developmental changes, came up with the T65E3. It was adopted by NATO on December 15, 1953. Several other nations offered their own cartridge designs for NATO testing, but the U.S. was adamant that its cartridges should be picked. It’s easy to see why. The .30-06 served admirably in Model 1903s, Model 1917s and M1 Garands for a half-century. The new 7.62x51mm was simply the ’06 packaged in a shorter case (2.494 versus 2.015 inches). Military specifications called for a 150-grain FMJ bullet at 2,750 fps – almost exactly the same as .30-06 M2 Ball.

Even after both the U.S. Army and U.S. Marine Corps infantry were equipped with M16s, the latter outfit’s snipers used a 7.62mm NATO military version of Remington’s bolt-action Model 700V called the M40, and the U.S. Army scoped some M14s and called them M21s. If the 7.62mm NATO was so good, why did the U.S. go to the 5.56mm? M16s were 2 to 3 pounds lighter than M14s, and a 20-round magazine of 5.56mm weighs half of a like capacity 7.62mm magazine. Perhaps most importantly, an M16 full-auto firing a 55-grain bullet is far more controllable than an M14 firing a 150-grain bullet.

My .308 Winchester handloading began with hunting rifles, Browning BLRs and a Remington Model 600. With those lightweights (actually carbines), 150-grain bullets were favored due to the recoil factor. With 180-grain bullets that little Remington’s forearm would jump off the sandbag several inches. In 1980, I finally found a .308 sporter that suited me and it’s still here.

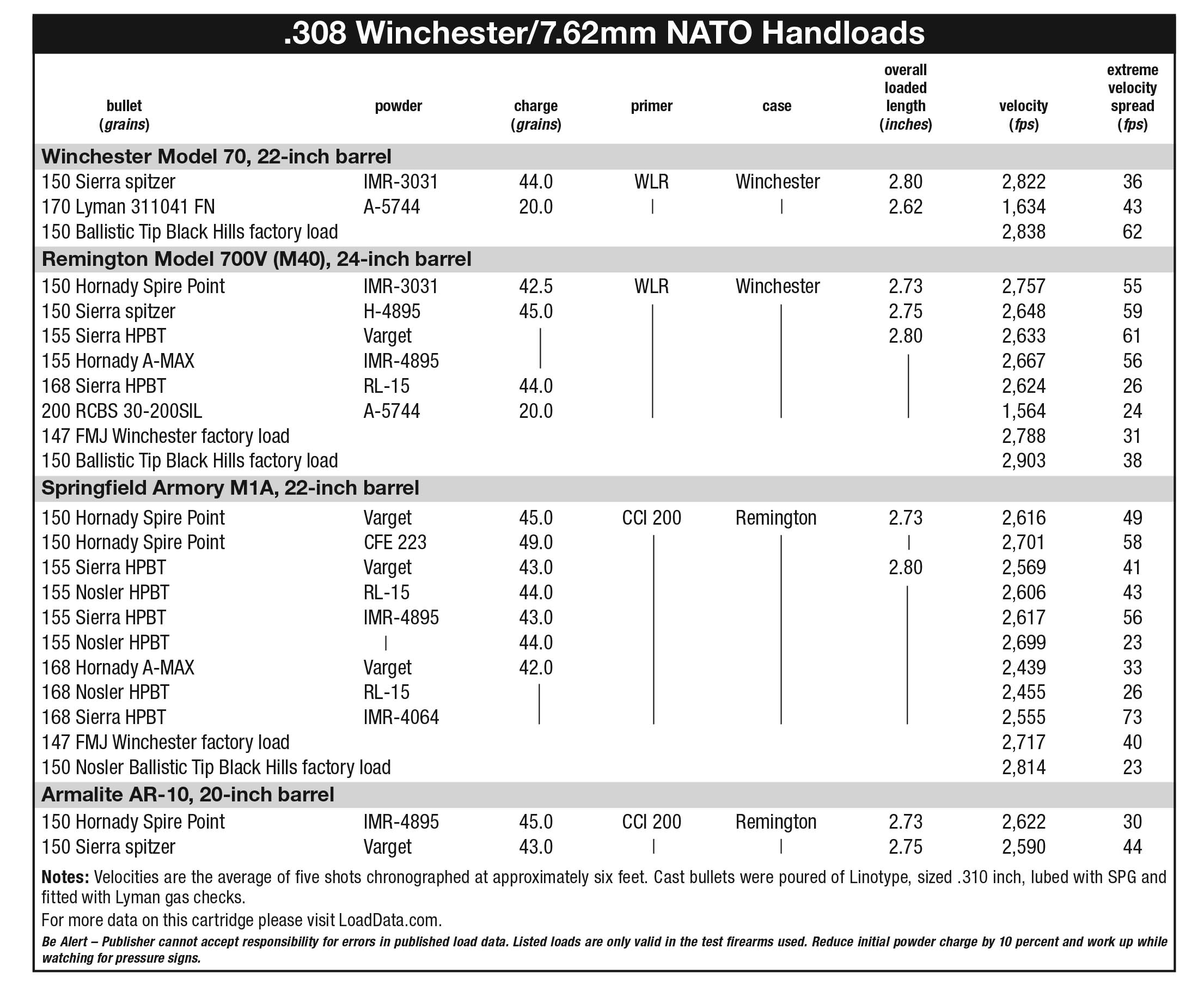

It was on a used-gun rack in a Bozeman, Montana, store. Someone had restocked a Winchester Model 70 Featherweight in Mannlicher style with straight grain walnut ending with a steel cap on one end and a rubber recoil pad on the other. Its serial number dated it as 1952 production, making it one of the first .308 Winchesters. Hunting season had already started, so quickly a good load was found. That was 44 grains of IMR-3031 with 150-grain Sierra spitzers and unremembered primers. Velocity exceeded 2,800 fps. Three shots often provided MOA accuracy, and five shots usually clustered into 1.5 MOA. Over the decades, primers and bullets have varied, but three things have been consistent: Winchester brass, 44 grains of IMR-3031 powder and a bullet weight of 150 grains.

One day when chronographing .308 loads, a friend visited. After watching a bit, he said, “If that Winchester wasn’t a .308 I’d try talking you out of it.” My answer was “Why not a .308?” He didn’t think the cartridge would be adequate for elk. That afternoon he had brought a sporterized Springfield Model 1903A3. His loads used the same Sierra 150-grain spitzers loaded over 59 grains of IMR-4350. We chronographed our loads side by side. His barrel was 24 inches long; mine was 22 inches. My spitzers were shooting over 50 fps faster than his, so we both learned a lesson.

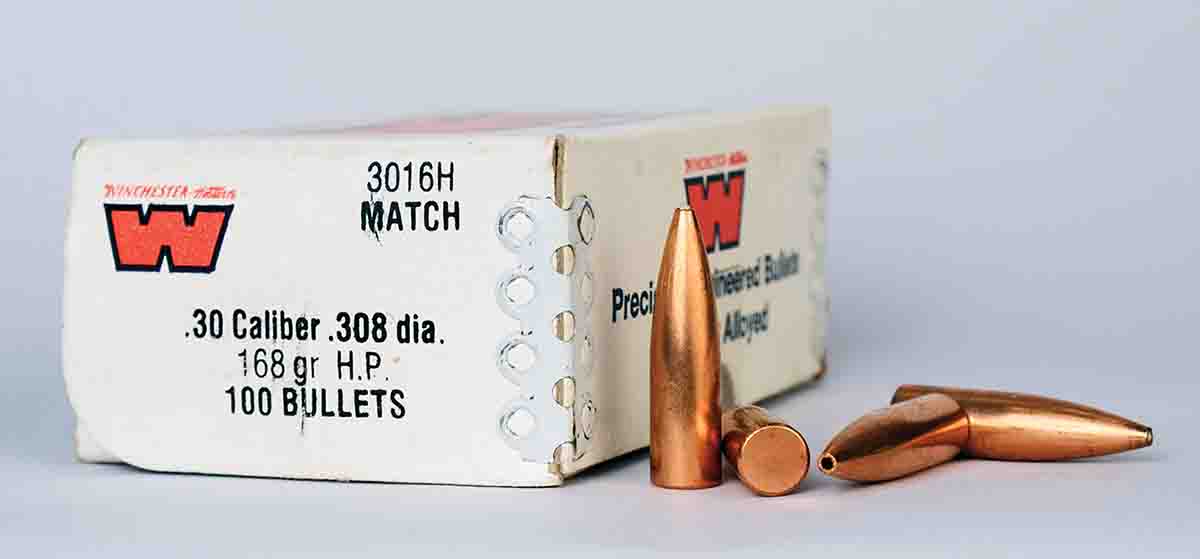

During this time my .308 interest expanded to target rifles. Desiring one capable of tiny groups, I had a nice custom Mauser 98 target weight .30-06 with a badly pitted barrel rebarreled with a Shilen blank. It was of course chambered .308, was about 11⁄8 inch in diameter and 27 inches long. The Sierra manual I had at that time mentioned the company’s .308 test load with 168-grain HPBTs was 37 grains of IMR-3031. I copied it directly and got .5-inch to slightly larger groups for five shots at 100 yards. Back then Winchester sold bullets for handloaders in distinctive white boxes. Its 168-grain target bullet was a flat base. To my surprise it would usually group under a half-inch with no other changes. I probably wasn’t the only handloader heart-broken when Winchester discontinued its bullet line.

My interests in .308/7.62mm began to expand into the area of military style semiautos. Up to this point, .308 handloading had been easy. For the heavy-barreled target rifle, cases were only neck-sized and never needed trimming. Even though that Model 98 had a magazine it was only used as a single shot. Therefore, overall cartridge length was ignored. Bullets were seated as far out as possible, short of being jammed into the rifling.

More recently I acquired an Armalite AR-10 and a DS Arms FN FAL SA58. Some of those military style 7.62mm NATO semiautos fed and functioned perfectly with cases sized full length as used in my Model 70, and some did not.

That was immediately evident when a handload stuck in an M1A’s chamber. It wouldn’t enter enough to fire and getting it free safely required two sets of hands. One set held the rifle pointed safely (outdoors) while the other set of hands held a block of wood on the operating rod handle and tapped (whacked) it with a hammer to free the cartridge. A small base sizing die was the solution, and semiauto .308/7.62mm NATOs have never given a bit of trouble since.

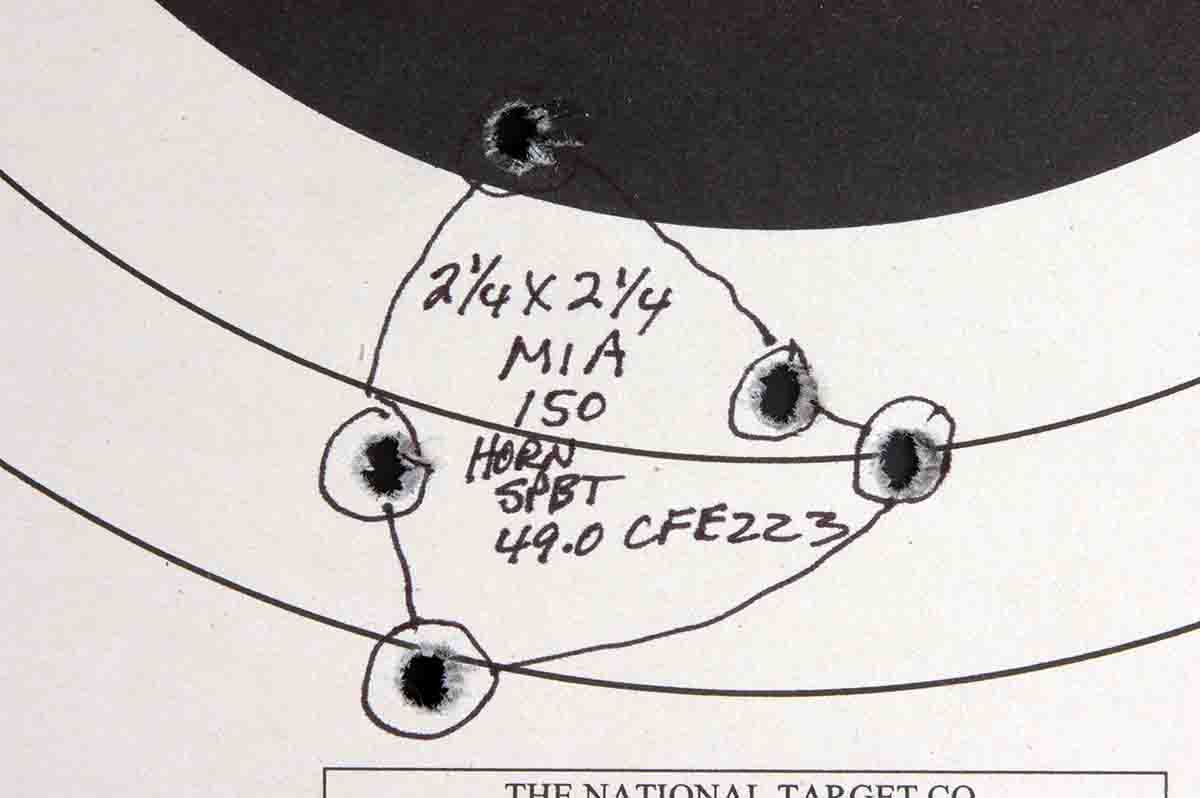

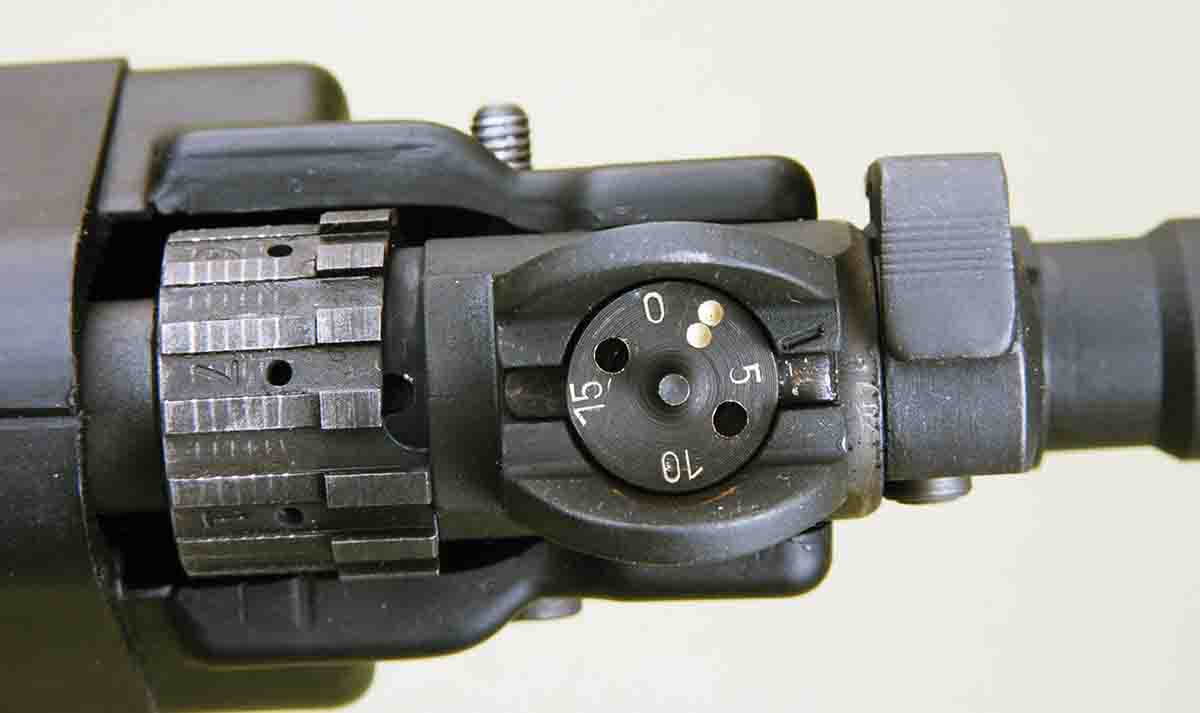

Some of my military .308/7.62mm NATO rifles shot very well. When scoped, I’ve received 100-yard groups under 1.5 inches. Iron sighted, they have been more in the 2- to 3-MOA range. With their iron sights, the AR-10 and FN FAL have usually grouped into 3 or 4 MOA, and occasionally slightly less. They all functioned perfectly with proper handloads and all factory loads, including some military surplus. The FN FAL is interesting in that its gas system is easily adjustable externally. That feature probably came in handy because about 70 nations adopted them at one time or another, and 7.62mm NATO military ammunition has been made pretty much worldwide. There had to be pressure and velocity differences. An adjustable gas system had to be a boon.

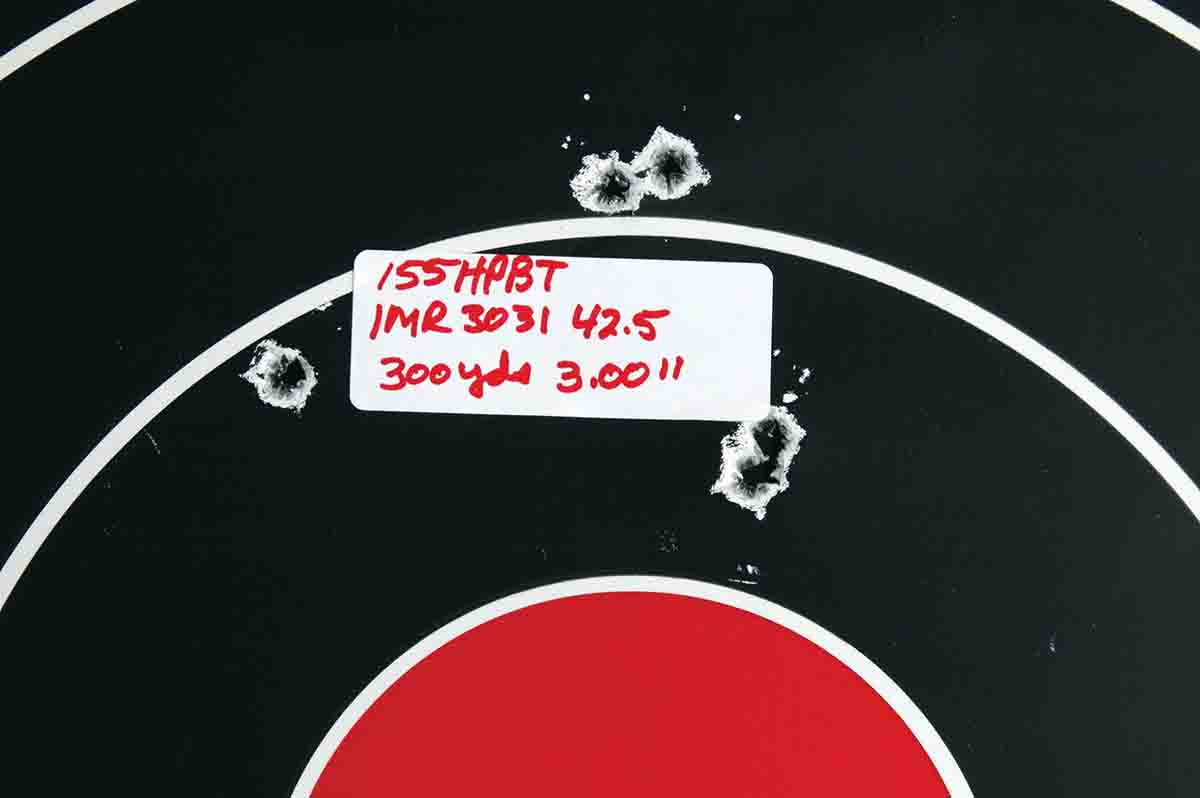

Thus far readers may have noticed that all my early .308 Winchester handloads for bolt actions were built upon only one powder. Nowadays, there are many more available. Therefore, with the semiautos newer propellants have been tried along with some old timers. Propellants tried have included Varget, CFE 223, Reloder 15, IMR-4064 and both IMR and Hodgdon 4895. It would be hard to choose one above the other for semiauto use. All are in the proper burning rate range. Considering they have been fired in several different rifles, I’d venture that on the average their groups have been more or less equal.

My .308/7.62mm NATO handloading efforts have focused mostly on 150/155-grain bullets but with some attention paid to 168-grain HPBTs. A point of note is that while .30-06 military rifles had rifling twist rates of 1:10, the .308 Winchester/7.62mm NATO has used one turn in 12 inches (1:12). With iron sighted military style rifles, no difference seems to arise between common hunting bullets and HPBT target bullets. However, both of those types beat FMJs in group shooting.

If there was an “everyman’s” title given to a cartridge, it would have to be the .308 Winchester/7.62mm NATO. It fills quite a few niches for riflemen, from cast bullet shooters to big-game hunters to target competitors.