Practical Handloading

Metallic Case Crimping

column By: Rick Jamison | February, 20

Another reason for a bullet to move in a rifle case is too much powder compression. This may not be noticed immediately after a bullet is seated, but after a few minutes a caliper may indicate that overall cartridge length has increased, again altering cartridge performance.

In a rifle or carbine with a tube magazine, heavy magazine spring tension or an extra hard push of a thumb while attempting to force another round into an already full magazine can move a bullet deeper within a cartridge case.

With a revolver, harsh recoil from big cases and heavy bullets may cause bullets to slide forward in the case, and bullets that move too far forward can jam a cylinder, preventing it from rotating. A semiauto pistol bullet not secured in a case mouth can also move during feeding and chambering.

These are a few of the reasons why bullets move in cases and why crimping may be required. I say “may” be required because there are other solutions. For example, I once had a .300 Winchester Magnum that favored Sierra 180-grain spitzers. However, with the dies I used, bullets were driven deeper inside cases under the force of recoil when they were bashed into the forward face of the magazine box. The bullet mentioned does not have a cannelure needed for crimping. I did not want to switch to another bullet, so after sizing fired cases normally, I removed the expander plug from the die and sized them again, thereby further reducing neck diameter and increasing case neck tension on the bullets. Bullets no longer moved during recoil.

Case neck tension alone is frequently all that’s needed to secure a bullet. A case full of powder also helps prevent a bullet from being pushed further into a case; just do not compress the powder too much.

Secondly, cases must be trimmed to the same length so that an equal amount of crimp is applied to all loads. A too-short case can prevent it from being crimped at all. A long case causes the mouth to be crimped excessively. An excessive crimp can produce a bulge or wrinkle in a case neck and prevent the round from chambering. A bullet can also be damaged by excessive crimping so that the jacket breaks off at the crimp line during expansion as when crimping without a cannelure.

Third, a crimp die must be adjusted so that the case mouth aligns with a bullet’s cannelure or relief groove. By “relief groove,” as opposed to “cannelure,” I refer to rifle bullets such as the Swift A-Frame or Barnes solid copper bullets. Because of the cannelure or relief groove location, there is little to no leeway on bullet seating depth.

If you are going to crimp, make sure when you buy bullets that the cannelure is in the proper location for your firearm. There are bullets that will not function in revolvers when the case mouth is aligned with a cannelure, and there are bullets with cannelures not located for proper feeding when loading for carbines or rifles.

Some bullets have dual cannelures to accommodate different cartridges or firearms. For example, the former 300-grain Speer .429-inch bullet for use in the .444 Marlin should be crimped in the front cannelure. The same bullet should be crimped in the rear cannelure when used in most .44 Magnum revolvers. Just make certain that such a cartridge is not too long for the revolver cylinder or chamber in use. Speer’s 350- and 400-grain .458 bullets are another example of bullets with dual cannelures for various firearms and cartridges. Hornady has also made bullets with dual cannelures. The above three requirements are limitations that can cause problems and are some of the reasons that a crimp is best avoided if possible.

Also, straight-walled and rimless cases popular in semiauto pistol cartridges headspace on the case mouth so that a handloader must take care and not alter headspace by over-crimping. In this situation, use a minimal taper crimp if crimping is necessary. A handloader can test loaded rounds to see if there is enough neck tension or crimp to secure a bullet by simply pushing the bullet of a sample round against the edge of a wood loading bench. If you cannot move the bullet with finger force, it is likely secure enough. Straight-sided pistol case walls taper internally and this also helps prevent a bullet being pushed too deeply into a case.

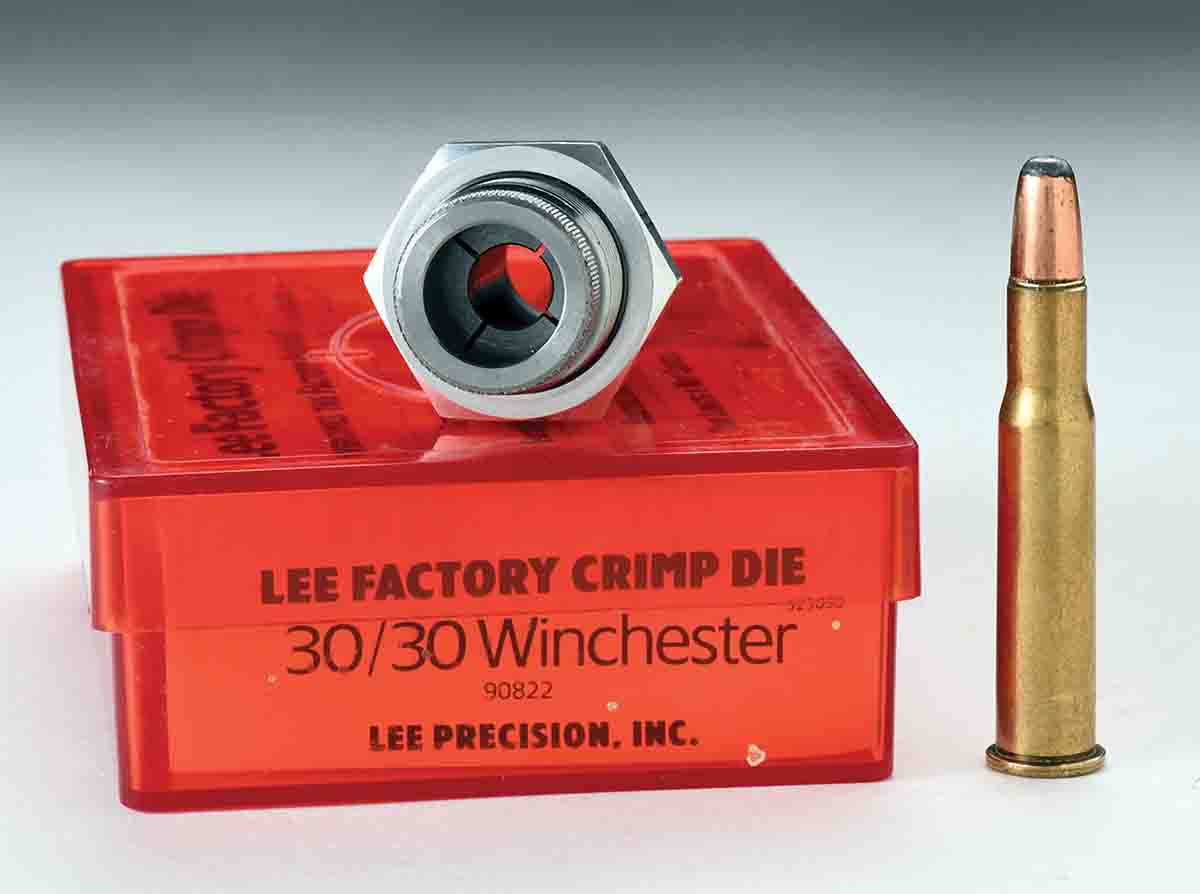

Most readers know that a beveled shoulder or step inside a die is what applies a crimp. Adjusting a die up or down in a press frame is the means to apply the proper crimp when a press ram is raised. As mentioned, a taper crimp is best for semiauto pistol cartridges and a roll (rounded) crimp is for revolver cartridges. Lee makes a Factory Crimp Die that utilizes a collet much like in a collet bullet puller. Redding even supplies a Micro Adjustable Crimp Die for several calibers.

There are arguments about applying a crimp while a bullet is being seated, as in a two-die rifle set. Some reloaders say a bullet must first be seated with no crimping applied, that a crimp should then be applied in a separate operation as with some three-die handgun cartridge sets. However, I have not found a problem with seating a bullet and crimping it simultaneously. Cartridges that need crimped cases (the .30-30 Winchester, .35 Remington, .44 Magnum, etc.) are not always intended for high accuracy shooting from precision firearms, and a shooter may not notice a difference in how a crimp is applied.