9x72R

A European Mystery

feature By: Terry Wieland |

Except for one thing: I have a rifle chambered for it, right here in my hand. It’s a J.P. Sauer & Sohn over/under hammer gun – an anomaly in itself – made in 1913, identified in the auction catalog as a 9.3x72R, but having a bore that measured .352 to .358 inch (9mm) rather than the typical .366 of a 9.3mm. It’s a puzzle, but a puzzle worth the effort to solve, because the gun itself is a honey.

This one is a masterpiece of German gun making. Not only is the mechanism ingenious, but it’s also as beautifully made as any gun you’ll ever see and it’s in lovely condition, considering it’s 110 years old. It may in the distant past have had some restoration but, if so, it was expertly done; the gun certainly appears original. The barrels are 28 inches, and the back-action locks allow a gracefully rounded frame. The rear trigger fires the shotgun, and the single-set front trigger the rifle. It weighs a neat 6½ pounds.

But back to the rifle caliber. A gun made in 1913 would have been subject to German proof, but the only marks on it relating specifically to the rifle barrel are the numbers “8.8” and “72,” and since 8.8mm is .346 inches, which suggests it’s the bore diameter. Yet the bore (by my measurement) is .352 (land) and .358 (groove.) This is almost exactly 9mm.

The 9.3x72R (.366 inch) was a standard German cartridge in the early 1900s, considerably less powerful than the more common 9.3x74R, the latter having a fatter case and more powder capacity. An RWS factory 9.3x72R cartridge will chamber in my rifle barrel, but a case with a handloaded .366-diameter, Hornady 286-grain bullet will not.

Probably, the factory RWS round will chamber because its bullet is dual-diameter, with a front section only .350 inch.

By a strange coincidence, I have a Johan Peterlongo (Austrian) SxS combination gun with what appear to be identical barrels – a 16-gauge shotgun and a rifle barrel of a caliber based on the same 9.3x72R case. The only difference is that the Peterlongo will accept the handloaded dummy cartridge with the .366 bullet.

In various sources, I found vague references to proprietary 9mm cartridges offered by both Sauer and Peterlongo, but no definite information and no ballistic data. I suspect I’ve come into possession of one of each. At any rate, I’m pursuing load development separately, beginning with the Sauer.

You now have all the facts I had when I started figuring out possible loads. Whether it would chamber or not, I was not about to pull the trigger on a cartridge with a .366 bullet in a rifle with a .358 bore. There is all sorts of information about this – and pseudo-information, opinion, speculation and outright guesswork – available online. Much of it is contradictory, and the inevitable conclusion is that there are a lot of different rifles out there, with different bore and chamber dimensions.

Finding all of this supremely unhelpful, I simply pursued a load using my own approach.

The first step was to pull out my trusty Powley Computer and begin measuring case capacity to see what powder it would recommend. For those not familiar with it, the Powley Computer is a cardboard “slide chart” calculator marketed in the 1960s. See “In Range” in this issue (page 66), and Handloader No. 290 (June-July 2014, page 64). It calculates the optimum load for any cartridge based on powder capacity, bullet diameter and sectional density.

When I say “optimum” load, this is neither a minimum nor a maximum; it is what Ballistician Homer S. Powley would regard as the most efficient. I went through all the steps – measuring case capacity in grains of water, determining the ratio of charge to bullet weight, and finally being pointed to the correct powder.

Being formulated in the 1950s, the Powley Computer used the most widely available powders at the time. These were eight IMR numbers from the fastest (IMR-4227) to the slowest (IMR-5010). With a 200-grain Hornady roundnose bullet, the Powley Computer indicated a load of 48 grains of IMR-3031. That struck my cautious soul as a tad on the lively side. But then I discovered something encouraging: The 9x72R has a case capacity, and bore diameter, identical to the 9x57 Mauser, a cartridge I’ve worked with in the past and even used as one example in the aforementioned Handloader article on the Powley computer.

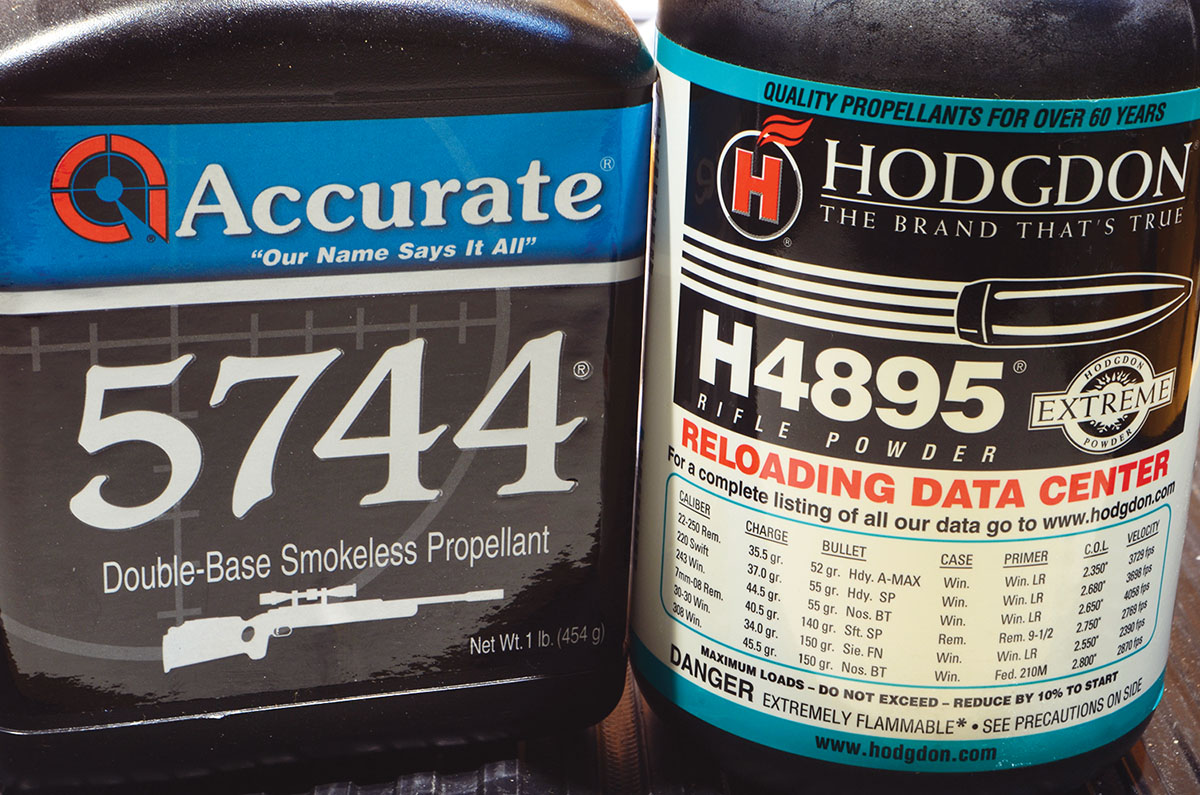

In 1965, Powley added an addendum to his user’s manual, stating that data for IMR-4064 and IMR-4895 could be used interchangeably. This is something to be approached with the utmost caution – powders have quirks – but useful to keep in mind. One of my best loads in the 9x57 used H-4895, so altogether I had a starting point.

For the sake of establishing a baseline, I tried some 5744 with cast bullets, first with a 158-grain bullet intended for the 38 Special, then with a 200-grain roundnose with a gas check. Both proved uneventful. So far, so good.

My next was 45 grains of H-4895 with the Hornady 200-grain roundnose. This delivered a very gratifying velocity of 2,191 feet per second (fps), with the fired cases simply dropping out of the chamber and no sign even of expansion, much less high pressure.

I then tried the same powder charge with Speer’s 180-grain Hot Core Flat Nose (HCFN). The average velocity was higher, so I dropped it back to 43 grains, erring on the safe side, resulting in a velocity of 2,338 fps and an astonishingly low (11 fps) Extreme Spread (ES).

Strangely, about every fourth or fifth shot, I would get an anomaly – a very low velocity, say 1,600 fps or, when shooting groups, a fifth shot that was an inexplicable flyer.

This was one of those occasions when the rifle’s sights dictated the load. Because the open sights have minimal adjustment capability, I had to try to formulate a load that would go where the sights were aligned and not really worry about bullet weight and velocity. With the 200-grain bullet, the rifle grouped about 4-inches high, and with the 180-grain bullet, it was 6-inches high. In both cases, however, the windage was almost perfect. The key to moving the group down, I figured, was either to reduce the powder charge, and hence velocity, or increase bullet weight.

I surmised that the original factory loading was probably a heavier bullet (the 9.3x72R uses a 286-grain bullet) so a heavier bullet at a lower velocity should bring the point of impact at 100 yards closer to the 80 meters engraved on the standing leaf sight. The folding leaf says “175,” but that is best ignored.

I finally decided the first load I tried, with the Hornady 200-grain roundnose, was probably the best I was going to get. The Hornady ballistic calculator told me that a group 4-inches high at 100 yards gave a zero of 190 yards and a 4-inch drop just shy of 225 yards – in other words, just about what I would set for such a rifle if I had a nice, adjustable Lyman aperture receiver sight.

Having settled that, I set about finding a low-powered load with lead bullets that would put the bullet at point of aim at about 50 yards – the usual range for armadillos and such in these parts. Going back to my original load with A-5744, I found that a 158-grain roundnose knocked over a 5-inch plate at 50 yards about four times out of five if I held on the bottom of the plate. Mission accomplished.

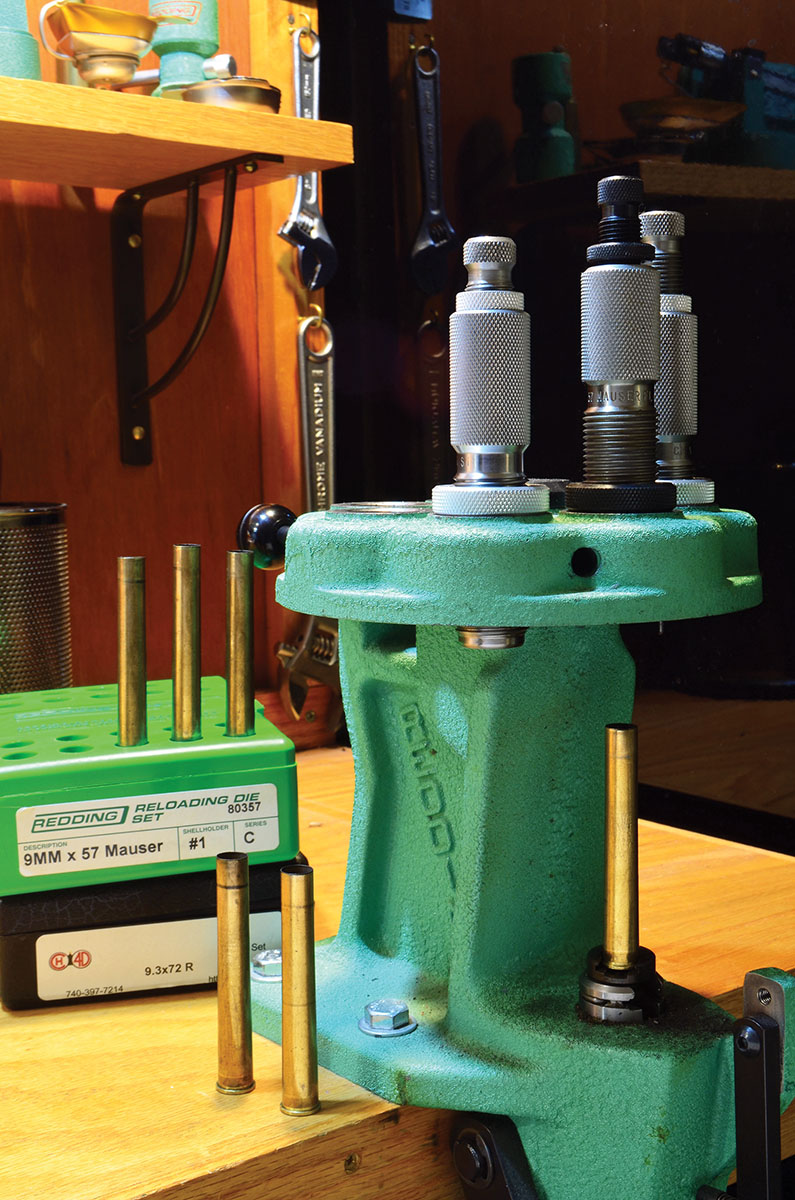

Loading my hybrid nine is not really difficult, but it requires some improvisation. A set of 9.3x72R dies does most of the work. By the way, when the fired case leaves the chamber, it measures exactly that of a 9.3x72, so a set of custom dies is not the answer even if I could get some during this time of strained production and long delays. Anyway, the 9.3 sizing die punches out the primer, and then running the case neck into a 9x57 sizing die far enough to reduce neck size results in a neat case with a shadow shoulder and a neck about .35 inch.

I use the 9.3x72R seating die to seat the bullet, then impart a crimp using a 9x57 seating die with the plug removed.

In this case, any number of .357-caliber dies might prove useful, including 358 Winchester, 350 Remington Magnum or 358 Norma.

Throughout the whole process, I did not encounter a single problem with the usual signs of adverse pressure, such as flattened primers or difficult extraction. Resizing the brass was effortless.

At some point, I may try to find an alternative load or two, but as long as I can get H-4895, I don’t see much point to it. I have a midrange big-game load with a bullet of proven value (200-grain roundnose) that will more than match the 35 Remington, and a short-range cast-bullet load with more power than a 357 Magnum.

Considering I started with a rifle in a caliber that, on paper at least, does not even exist, that’s a pretty good outcome.

.jpg)