In Range

The Timeless Powley

column By: Terry Wieland | February, 24

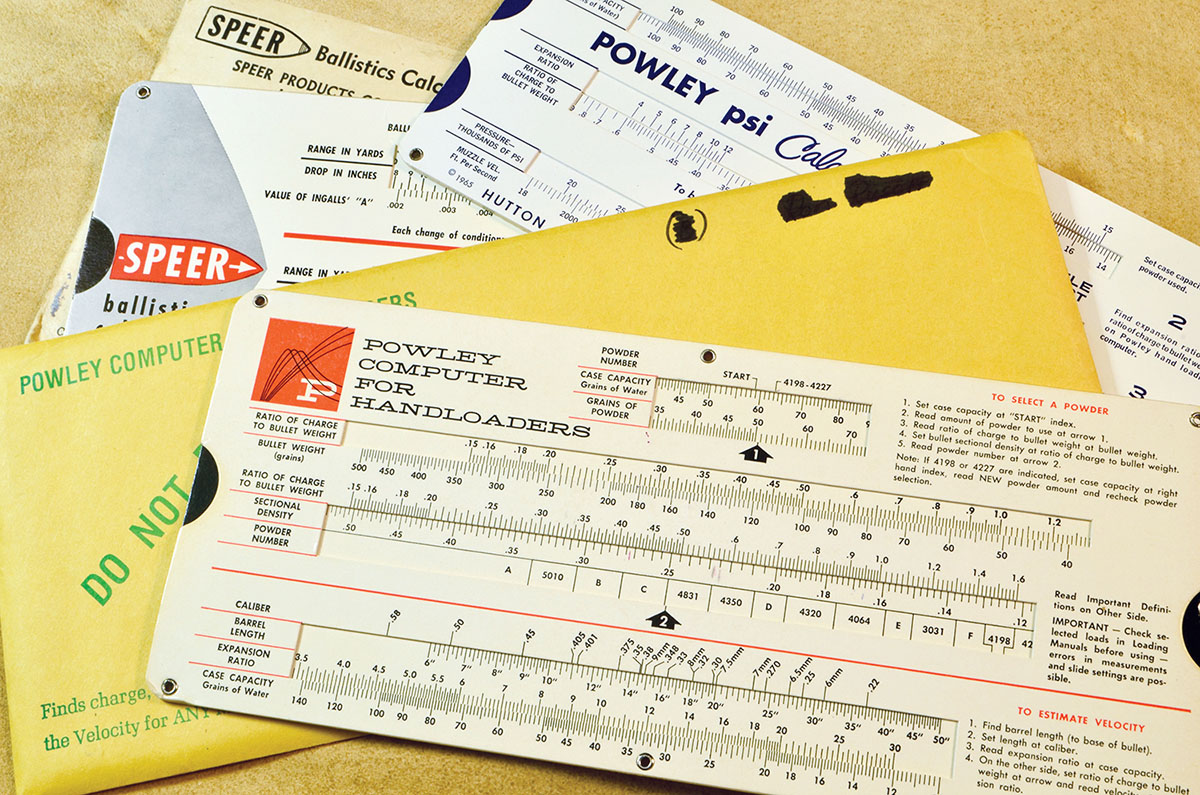

In the early 1960s, Ballistician Homer S. Powley perfected an idea for a handloader’s ballistics and powder-charge calculator using the principle of a slide rule, but made of high-quality coated cardboard instead of the usual wood or plastic. It was called a “slide chart.”

This consisted of a card inside a sleeve with windows, scales and various witness marks. Using cardboard would allow them to be mass produced cheaply, putting them within financial reach of any serious handloader. The device was called the “Powley Computer for Handloaders.”

Slide charts were not new; they were then in vogue for calculating everything from gas mileage to flower-planting schedules. In fact, a few years earlier, Speer had marketed one purported to give bullet drop and velocities, and that may have sparked Powley’s idea. More about that later.

To produce the computer itself, Powley went to a company that specialized in such things. By an extraordinary coincidence – here’s the serendipity – the company employed a guy named Bob Forker, an enthusiastic (not to say fanatical) shooter and handloader.

Forker contacted Guns & Ammo handloading writer Bob Hutton, who had a property in California called the Hutton Rifle Ranch. Together with Powley, they created a small company. Hutton’s wife, Marion, handled the marketing and the Powley Computer was on its way.

This all took place long before personal chronographs, or even handheld calculators, and the word “computer” was not associated with iMacs. It was a time of printed information and, in the case of some published handloading data, information that was often questionable and almost impossible to cross-check.

For handloaders today, multiple sources of information are almost a birthright. In fact, if anything, we have too much information, scattered anywhere and everywhere, and much of it is downright suspect. In Powley’s day, there were only two major loading manuals – Lyman-Ideal and Speer – whereas today, almost every bullet and powder manufacturer publishes one and Hodgdon has its softcover “annual manual.” This is not even to mention various online sources.

Despite this, there is still a need for basic information one can calculate without resorting to manuals. This is often the case with older cartridges, such as, say, the 30 Remington or 25 Remington, which are not listed in newer manuals because space is at a premium. Yet, if you find them in an old manual, they may call for powders that have been long-since discontinued.

Also, many European cartridges, chambered in rifles that have found their way to this country, may never have been listed at all, anywhere. What then?

The Powley Computer approaches the problem from the viewpoint of a professional ballistician interested in burning efficiency and optimal ratios rather than velocities or accuracy. Powley’s basic unit of information was not caliber or bullet weight but case capacity. Case capacity in grains of water, to the base of the bullet, allowed him to calculate the optimum powder charge. From there, moving the slide to accommodate bullet weight (giving the ratio of charge to bullet weight), you then position this ratio against the sectional density of your bullet, and another line tells what powder to use.

The powders, of course, were those available in 1960. That’s the bad news. The good news is that most of those old IMR powders – 4227, 4198, 3031, 4064, 4320, 4350, 4831 and 5010 – are still available and likely to be for a long time. Of these, 5010 disappeared long ago, and 4320 was only recently discontinued, but that still leaves a more than adequate selection.

The list requires a little clarification. The 4831 referred to is the original, now known as H-4831, since IMR-4831 was not introduced until 1973. While they are close in performance, they are most emphatically not interchangeable. Later, Powley informed us that 4895 could be substituted where the computer called for 4064. Since Powley did not say which 4895 he meant, we should assume it was Hodgdon’s, since IMR-4895 did not come on the scene until 1962. Only then did we see the use of the prefixes “H” and “IMR.” H-4895 is one of the most useful, versatile, and forgiving powders around, so this is very helpful, but it should still be approached with caution.

Something else to keep in mind is that case capacities can change, sometimes quite drastically, as cases are redesigned or produced by a new manufacturer. The 22 Hornet is a classic example. Its case was redesigned around 1950, but no one bothered to tell most of us. Often, such information is hidden in a footnote in a book we may not have. The Hornet was strengthened by giving it thicker walls, but capacity was reduced, leading to higher (!) pressures with loads that had been perfectly safe a decade earlier, but now might lock an action up tight as a drum, if not worse. (I experienced worse, with a 22 K-Hornet incapacitating a BSA Martini action.)

Had I used some of the new brass to calculate a starting load using the Powley Computer, the difference in case capacity would have been taken into account, which would have led me to a suitable charge, probably using IMR-4227 and all would have been rosy.

Alternatively, I could have used the Powley computer to cross-check the load I was using, which came from Philip B. Sharpe’s Complete Guide to Handloading, and dated from the 1940s. My guilty load, 11.5 grains of IMR-4227 with a 45-grain bullet, was two full grains less than Sharpe’s heaviest published load, which was not even identified as maximum. Yet, one shot locked up and damaged the action.

In that instance, having seriously reduced the load, I was sure I was on perfectly safe ground. I was wrong.

Admittedly, the Powley Computer is not simple to use. Unlike today’s programs online, you do not just punch in a bunch of numbers and have the information flash up on the screen. It does, however, come with a detailed instruction pamphlet that explains everything, unlike the earlier Speer calculator that is, frankly, to me, incomprehensible.

I asked Lane Pearce, another handloading writer who spent his career with NASA (to Lane, it really is rocket science) and he told me he bought the Speer computer 30 years ago, tried to use it, couldn’t understand a word, and put it away in a drawer, never to look at it again until now. This, is from an engineer!

The Powley Computer, on the other hand, he said he consults a half-dozen times a year. Nothing has ever come along to replace it.

Many shooters now use QuickLoad, which is part of a suite of computer programs offered by a German company. I tried it 15 years ago, even going to the extent of buying a Windows laptop for the purpose, since it will not run on a Mac. For whatever reason, I could never get it to work and finally gave up.

Lane doesn’t use it either because, he told me, he’s been given some QuickLoad powder/bullet combinations that, when he cross-checked with other sources, he found to be frighteningly high. Not all, but some.

This does not mean QuickLoad is not useful, but it’s one more reason to emphasize caution and cross-checking wherever possible and if cross-checking is not possible, redouble the caution.

A few years after the Powley Computer, the company produced a second slide chart, the PSI Calculator.

It required the use of a “desktop chronograph,” which is neither as easy nor as practically useful as its brethren, and its readings, I’m told, don’t really correspond to pounds per square inch as we measure it today. Still, good to have.

When I wrote about the Powley here first, a decade ago, you could find them on eBay, almost always in near-pristine condition with the instruction pamphlet, in the original mailing envelope. It seems buyers were neat, careful types who looked after things.

Anyway, I could get one for $10 or so; when I went looking last week, I found three, all asking $50 plus shipping. Worth the price? Absolutely.