Cartridge Board

7.7x58mm Japanese

column By: Gil Sengel | February, 24

The chronicles tell us that in the mid-sixteenth century, Dutch merchants brought matchlocks to one of the Japanese islands. When the guys in charge saw what the crude guns could do, they wanted more, along with being taught how to make them and how to produce gunpowder. The Dutch obliged. It was, as usual, the common folks who suffered.

It took a while to begin to change this situation because the country had no industrial base – everything was handmade. The state had never allowed common folks to own guns. They were expected to be born, work to support the elite and then die. Thus, there were no firearms designers, inventors, shooting clubs, target shooters or ranges – nothing relating to firearms. The Japanese had no choice but to import military muskets from Holland. This began about 1859, along with an industry in Japan to copy them.

The adoption of the first Japanese-designed long arm occurred in 1880. It was a single-shot cartridge rifle credited to Col. Tsuneyoshi Murata, though obviously “influenced” by the Mauser and Chassepot designs. The cartridge fired was known as the 11mm Murata, but was difficult to tell from the 11x59mm Gras (French) or 11.15mm Mauser without a micrometer. A 416-grain, .430-inch diameter bullet was loaded ahead of 85 grains of black powder in a drawn brass case. The round and rifle are often called the Type 13 or 11mm Meiji-13, indicating the thirteenth year of the reign of Emperor Meiji (1880). Also, with German help, drawn brass cases were being made in Japan by 1883.

In France, Paul Vieille produced the first commercially viable smokeless powder in 1886, which quickly led to the 8mm Lebel and 7.92x57mm military rounds. Surprisingly, the Japanese had a magazine rifle design by 1887 that used a tubular magazine like the Mauser and Kropatschek. It chambered a cartridge called the 8x53Rmm Murata, but was just the earlier 8mm Mannlicher. Since this was too early for smokeless powder to be available, it is assumed the early cartridges were loaded with compressed black powder like the 303 British. In 1889, the Japanese produced their first smokeless powder and began loading the 8mm Murata with it. The only ballistic data that could be found listed a 238-grain jacked bullet achieving 1,850 feet per second (fps) from a 29.5-inch barrel.

It is written that Japanese troops did not like the recoil produced by the 8mm Murata, or the rifle firing it. Superintendent of the Tokyo Arsenal, Col. Nariakira Arisaka, began work on a new design that would bear his name even though some references credit Col. Murata as the major contributor. The rifle was, however, basically a Mauser design.

At any rate, both the new rifle, titled Meiji-30 or Type 30, and the cartridge for it, called the 6.5x50mm Arisaka, began production in February 1899. The first loading pushed a very blunt roundnose bullet of about 160 grains to near 2,300 fps from a 30.5-inch barrel. Neither the rifle nor the original loading lasted very long.

By 1905, construction of the Type 30 bolt had been simplified and its title changed to Type 38 rifle (30.5-inch barrel) and Type 44 carbine (18.5-inch barrel). The loading of the 6.5mm Arisaka changed at the same time to a sharply pointed 137-grain bullet developing 2,500 fps from the rifle barrel.

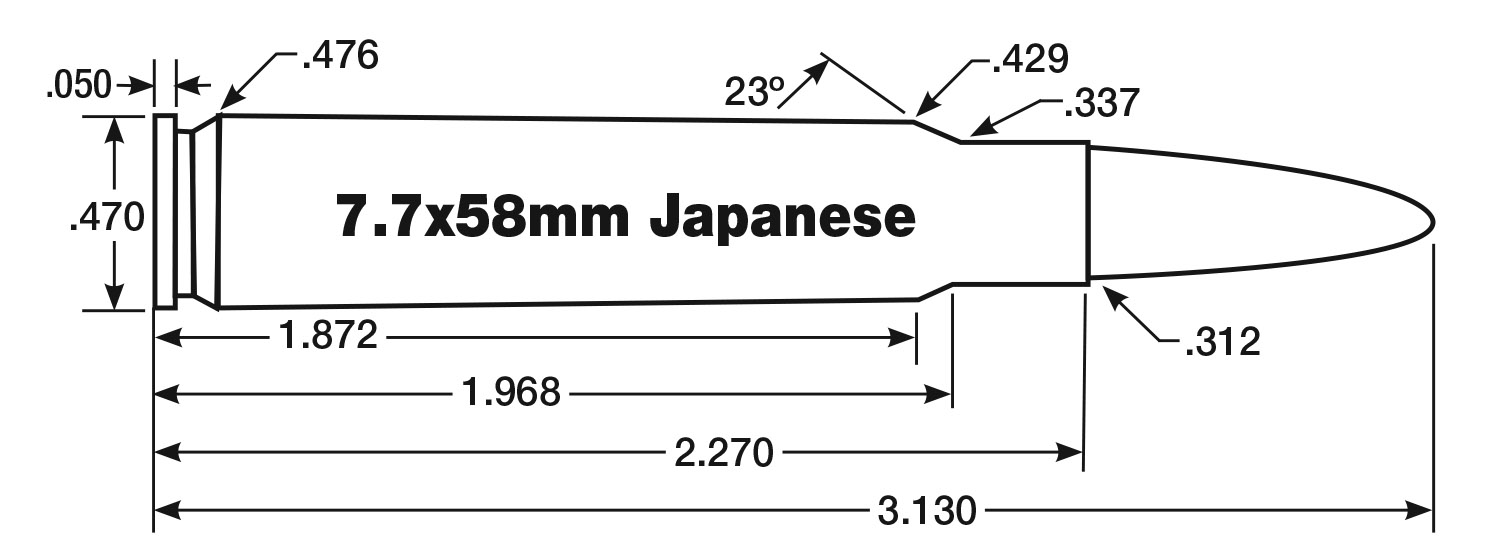

When Japan invaded China in 1937, combat experience showed the 6.5mm Arisaka Type 38 rifle and machine guns were totally inadequate. However, a more powerful round had been taken under development since 1929 for machine guns. This was the 7.7x58SRmm, (SR meaning semi-rimmed). By 1939, this round had lost its semi-rim and was a modern rimless cartridge known simply as the 7.7x58mm. Several machine guns and a new infantry rifle called the Type 99 with either a 30.75- or 25.2-inch barrel became available. The normal range of military loadings was produced (mostly for machine guns) including tracer, armor piercing, incendiary and explosive. The infantry rifle load was a 175-grain pointed full-jacket bullet reaching 2,400 fps from the long barrel.

Even though the Type 99 was technically Japan’s main battle during World War II, the Type 38 continued in production because the new rifle could not be made fast enough. The number of surviving M99s is not known since many were lost or abandoned in the jungles of the South Pacific, blown up with captured ammunition dumps, or sent to the bottom before issue courtesy of the U.S. Navy. Nevertheless, they were available on the surplus market for awhile and were seen as war trophies brought back by returning GIs.

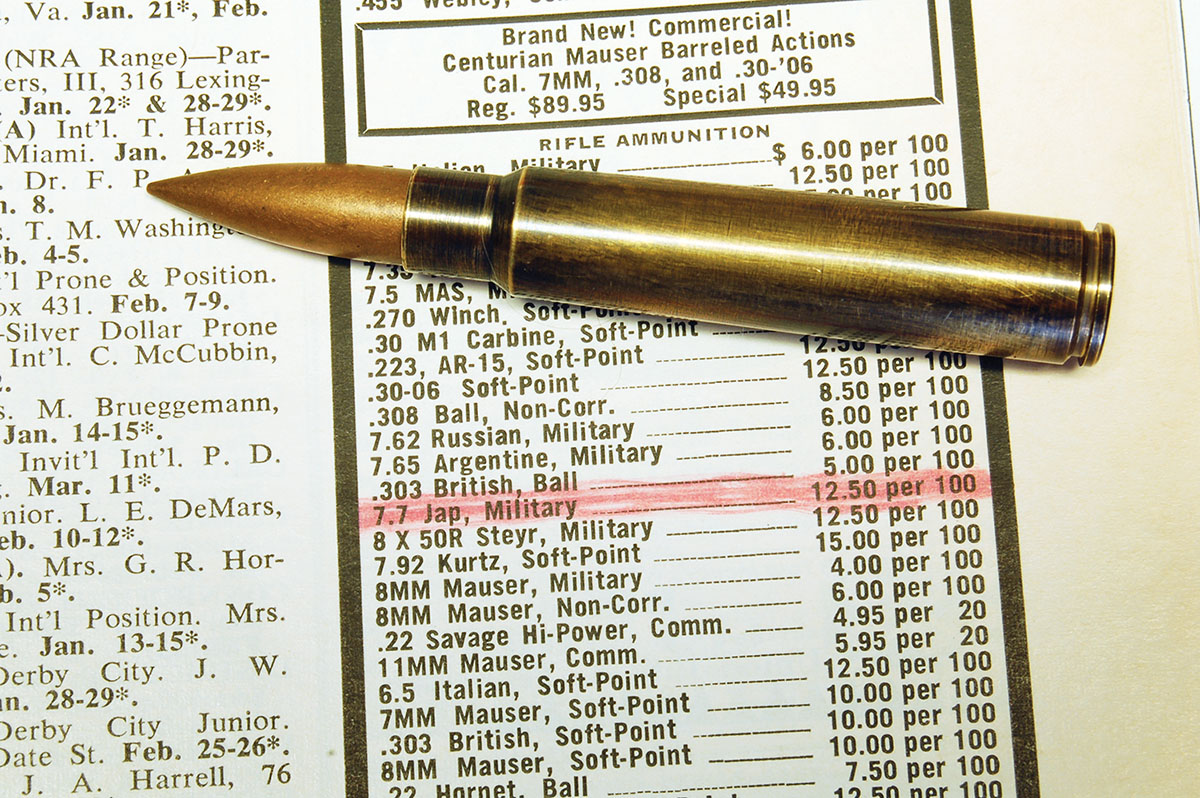

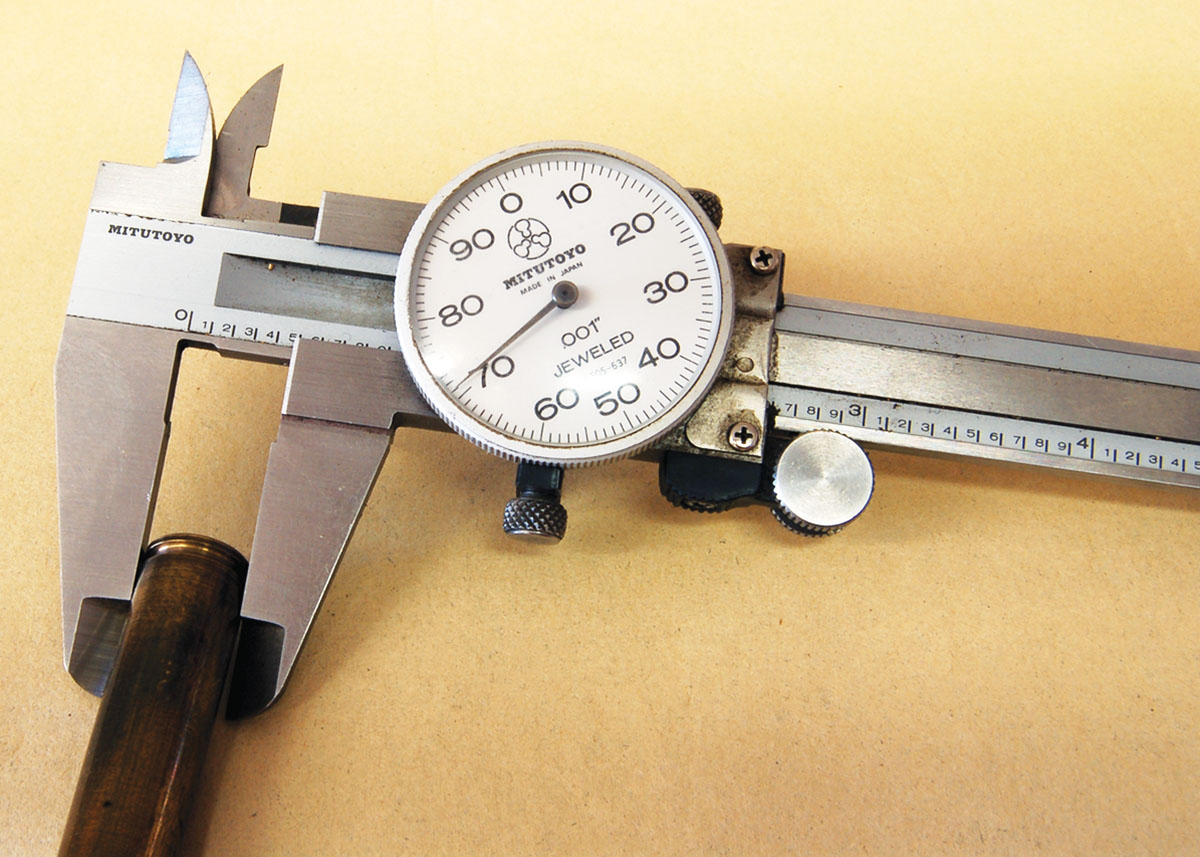

Many individuals today would like to shoot the Japanese Type 99 rifle if they could find one. Though surplus ammunition is long gone, Norinco, Prvi Partizan and Norma have recently listed ammunition and Prvi Partizan also offers empty cases. Since the 7.7x58mm has the same base diameter as the 30-06, cases can be formed from it, which is what I did more than 40 years ago. Today, some references warn against this, or even firing these rifles at all. They say sloppy war-time chambers cause case failure and rifle blow-ups. Maybe I was just lucky, but cases were loaded several times and were sold with the rifle.

The Type 99 Japanese rifle and its cartridge are of special interest to me because of its use in the savage jungle fighting of World War II. They are relics of a past that we are now being encouraged to forget but do so at our own peril.

.jpg)