Beginning Bullet Casting Part III

Casting Good Bullets

feature By: Mike Venturino | April, 17

Once a reader e-mailed, saying his goal was to produce home-poured bullets that looked as good as those in Yvonne’s photos. As pleased as I was for the compliment, my response pointed out two things: First was to remember that I got to cherry-pick the bullets in Yvonne’s photos, and second was that I had decades of experience. Rendered down to its most simple meaning, point number two indicates I have made most of the mistakes contributing to poor quality bullets and hopefully learned how to correct them.

Let’s determine what defects are found in cast bullets. Common ones are wrinkles, rounded bands where there should be sharp edges, plugs pulled from the bullets’ bases upon cutting the sprue, frosted bullets and, the most damning of all, rounded bases.

Wrinkled bullets can be caused by many factors and can be the easiest or hardest of all problems to solve. Generally speaking, most wrinkles in bullets are caused by the alloy and/or the mould not being hot enough. Determining which one is easy. Set the bullet mould on the edge of the melting furnace while it heats the alloy. Then cast 10 or 15 bullets. If the wrinkles don’t disappear, then the alloy is not hot enough. In all but the smallest calibers, the mould should be at perfect casting temperature after 10 to 15 bullets are poured. If not, the remedy is simple – turn up the lead pot’s heat.

What if the heat is corrected, the sprues are taking more than a few seconds to cool but the wrinkles persist? Then the problem is in the mould itself. Oil or some other contaminate may be in the mould cavity. Here the remedy is cleaning moulds with a degreasing agent. Many are sold in gun cleaning sections of sporting goods stores or even in automotive parts stores. When I get a new bullet mould, I degrease its cavity, block faces and block tops. That is usually sufficient. Some preservative grease or oil will remain on non-important areas, such as screw holes or the slots for handles alongside each block. It will smoke as the mould comes to temperature but is nothing to worry about.

Living in a low humidity area in Montana, never after that first cleaning do I oil a bullet mould again. Of course, aluminum and brass blocks don’t rust anyway, but iron moulds will rust quickly in humid areas. I know, for I lived in southern West Virginia until graduating from college. In summer, moulds would begin rusting nearly as soon as the lead pot was turned off. In fact, when I began leaving to work summers in the West, no matter how much moulds were oiled or greased there would be some rust on them come September. The last time they were left behind, I put them in a coffee can filled with motor oil. They certainly didn’t rust then but were a mess to clean.

The third reason bullets will fall from a mould with wrinkles is just about impossible to deal with: The alloy has become contaminated. If the bullet mould’s cavity is clean with alloy temperatures properly high and bullets are still wrinkled, the culprit is the alloy. This usually happens when economy-minded individuals throw in any alloy that looks like it is lead-based. Lead, tin and antimony mix well and can combine to produce astoundingly accurate bullets. Throw in some mystery metal, and the entire pot of alloy can be rendered into a blend good for nothing more than doorstops or paperweights. Know what alloy is going into your lead pot, and this third wrinkle reason will never be a problem.

In my experience, 99 times out of 100 that cures the problem. Just days prior to this writing I accidentally set a favorite bullet mould atop my heated lead furnace while dropping in some old bullet lube for fluxing. The greasy soot produced flowed into the mould cavity between the blocks and on the bottom of the sprue plate. I feared the mould might be ruined with so much greasy crud on it, so it was liberally sprayed with degreaser, carefully wiped off with a cotton patch and the process repeated. Then the mould was used. My fears grew worse as it heated to good casting temperature but most bands remained rounded. A last resort was the kitchen match treatment, and I’m happy to report that bullet mould is producing 560-grain, .45-caliber bullets as good as ever.

Another cause for both rounded bands and bases is that the alloy is not entering the mould with enough force. For instance, if

Mentioned earlier was the word cadence. To produce good quality bullets, the caster needs to develop a cadence – striving to fill the mould, allowing it to cool and cutting the sprue the same every time. My wife knows not to interrupt me while casting, and I never take a phone call during a run of 100 to 115 casts. One fellow I know even uses a kitchen timer at his casting bench in order to keep each bullet identical to the previous one.

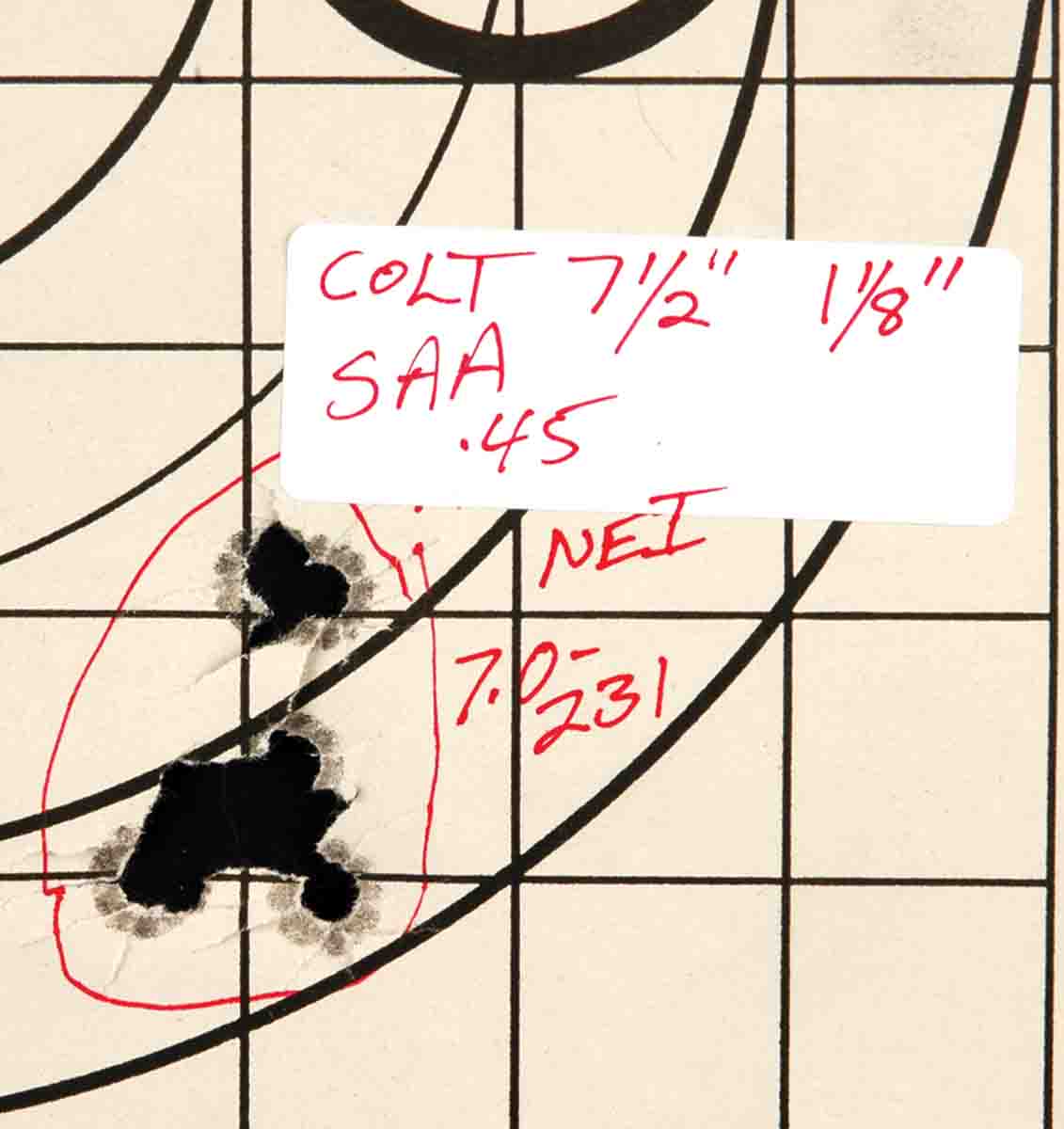

Now I’d like to contradict myself. The above paragraph refers to bullets used for competition, whether meant for 1,000-yard BPCR matches or 50-yard Bullseye pistol events. When casting casual shooting or speed competition bullets, I discard the cadence concept. Here we are talking more about quantity than quality. For many years I strove to make my handgun bullets just as perfect as my BPCR match bullets. Machine rest handgun testing of many thousands of rounds over a 40-year period convinced me that small wrinkles and minor imperfections in cast bullets make no difference whatsoever. In fact, for one test, some perfectly cast bullets and some visually imperfect ones from the same mould were loaded exactly alike and fired from an S&W Model 29 with 61⁄2-inch barrel at 25 yards in 12-round groups. The flawed bullets actually cut the smaller group by a minor amount.

This use of slightly flawed bullets carries over to rifles when speaking of shooting cast bullets in my collection of military bolt actions from 6.5mm to 8mm in caliber. Bullets are cast of straight Linotype in multiple-cavity moulds, gas checked when sized properly and then loaded. Most of my military rifles will put them in 11⁄4- to 2-MOA groups at 100 yards, depending on a given rifle’s bore condition and sighting equipment.

The key to getting away with casting quickly, and for quantity instead of quality, is to make sure bullet bases are perfect. Whereas minor wrinkles or flaws won’t matter except in precision competition, firing a bullet with a rounded base after one

A correlating factor here is the dreaded divot in a bullet’s base as the sprue is cut. Again, this is more damaging for precision bullets than those meant for speed competitions or for plinking. A plug pulled from the bullet base is caused primarily in two ways. It will happen if the alloy in the mould remains too hot when the sprue is cut. Not only will a plug get pulled from the bullet’s base, but alloy is also apt to get smeared across the block tops and even underneath the sprue plate. Another, more rare cause for plugs pulling from bullets’ bases can arise from a heavily used mould, and the edges of the sprue hole can become dull. Not many individual moulds suffer that affliction.

In order to speed up production and keep from getting divots in bullet bases and/or lead smeared across mould tops, I keep a high-speed manicurist’s fan to the left side of my lead pot. As soon as the mould is filled, it is set in front of the fan, which cools the sprue quickly. How many seconds a mould needs to be in front of the fan can only be determined by trial and error. Mine cool sufficiently in four to five seconds. This allows a smooth cut of the sprue plate.

The simple act of cutting the sprue plate is instrumental to good bullets. First off, the plate should be hit in the same plane as it swings. Hitting it with an up- or down-angled strike will cause warping. Most writings on beginning bullet casting recommend wood for striking the sprue plate. I have worn out several hammer handles or pieces of broken axe handles, but not

With all the above said, to end this segment, it should be stressed that while going to all the effort to cast good bullets – and plenty of them – there is no sense in ruining them during the handloading process. Therefore, the next and last chapter of “Beginning Bullet Casting” will consider that factor.