The Heavyweight .358 Norma

A Magnum Cartridge That Pulls No Punch

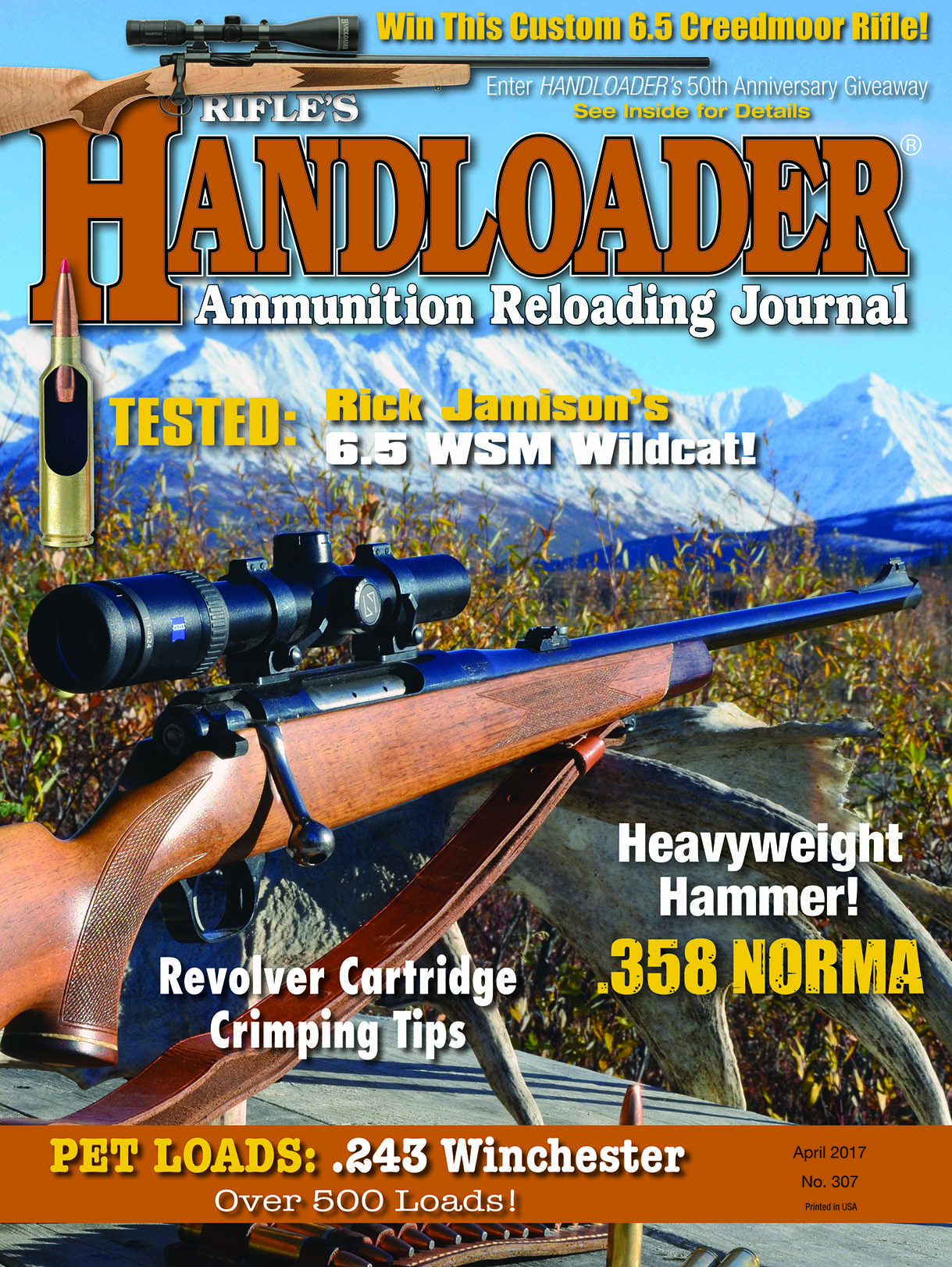

feature By: Terry Wieland | April, 17

By coincidence, in that same year, Norma Projektilfabrik of Sweden introduced its own heavyweight champion, the .358 Norma Magnum. For the next year, comparisons were inevitable between Johansson’s “Hammer of Thor” and the .358’s powerful 250-grain bullet. As it turned out, having a great punch was not enough for either one. There’s more to success than merely landing a good one on the chin.

In Johansson’s case, disdain for serious training left him vulnerable when the superbly conditioned Patterson came back a year later, gave him a dazzling boxing lesson and reclaimed the title. Meanwhile, the .358 Norma fizzled, for lack of a better term, because rifles were not readily available, ammunition was expensive and hard to get, and it found itself in direct competition with one of the great American cartridges of the twentieth century, Winchester’s .338 Magnum. In cartridges, as in boxing, what goes on behind the scenes often determines the outcome.

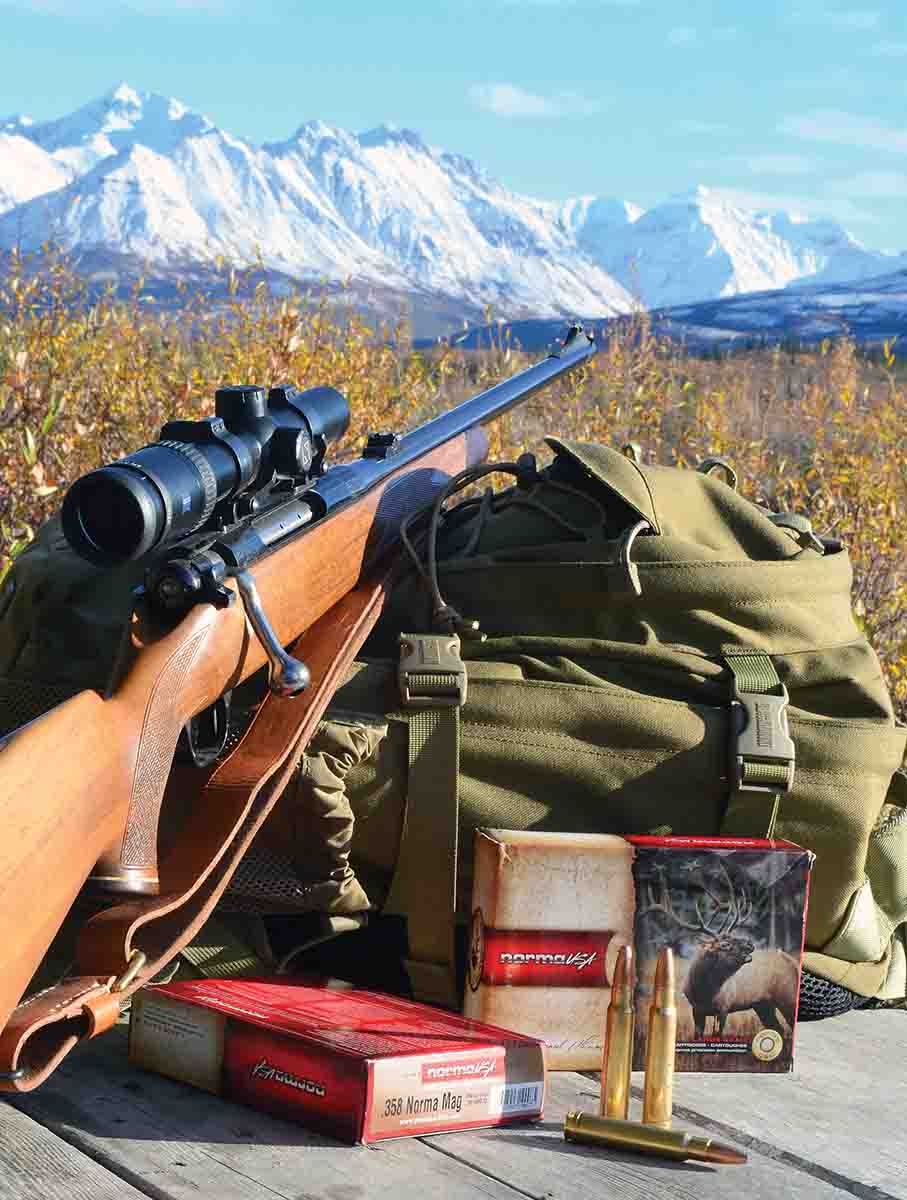

In any mass-production rifle, either the .375 or .338, or both, will be found as a standard chambering. Not so the .358 Norma. Today, it is strictly a custom proposition unless one of the original rifles chambered for it can be found. These were, primarily, the Schultz & Larsen (Denmark), the Husqvarna (Sweden) and a few Browning High Powers made by FN in Belgium. This list gives some idea of the .358 Norma’s status today: Those rifles rarely seem to come on the market. The fortunate few who own them want to keep them, and these are the core admirers who make it worth Norma’s while to continue offering brass and loaded ammunition.

It’s also worth noting that, in spite of its relative obscurity, the cartridge appears in many of the most recent loading manuals, including Norma’s own, a worthwhile addition to anyone’s reloading library. In the entry on the .358 Norma, it maintains that, had Norma convinced a major American riflemaker to offer the chambering in the early years, it could have become one of the greats. It also notes that the reconstituted Schultz & Larsen company is offering the chambering in its Model 97 takedown rifle. Alas, to the best of my knowledge, it’s not imported to the U.S.

This raises the obvious question: Why, with so many modern cartridges around of more or less equal power, chambered in readily available rifles, is there this lingering interest in, and loyalty to, the .358 Norma? What keeps it alive?

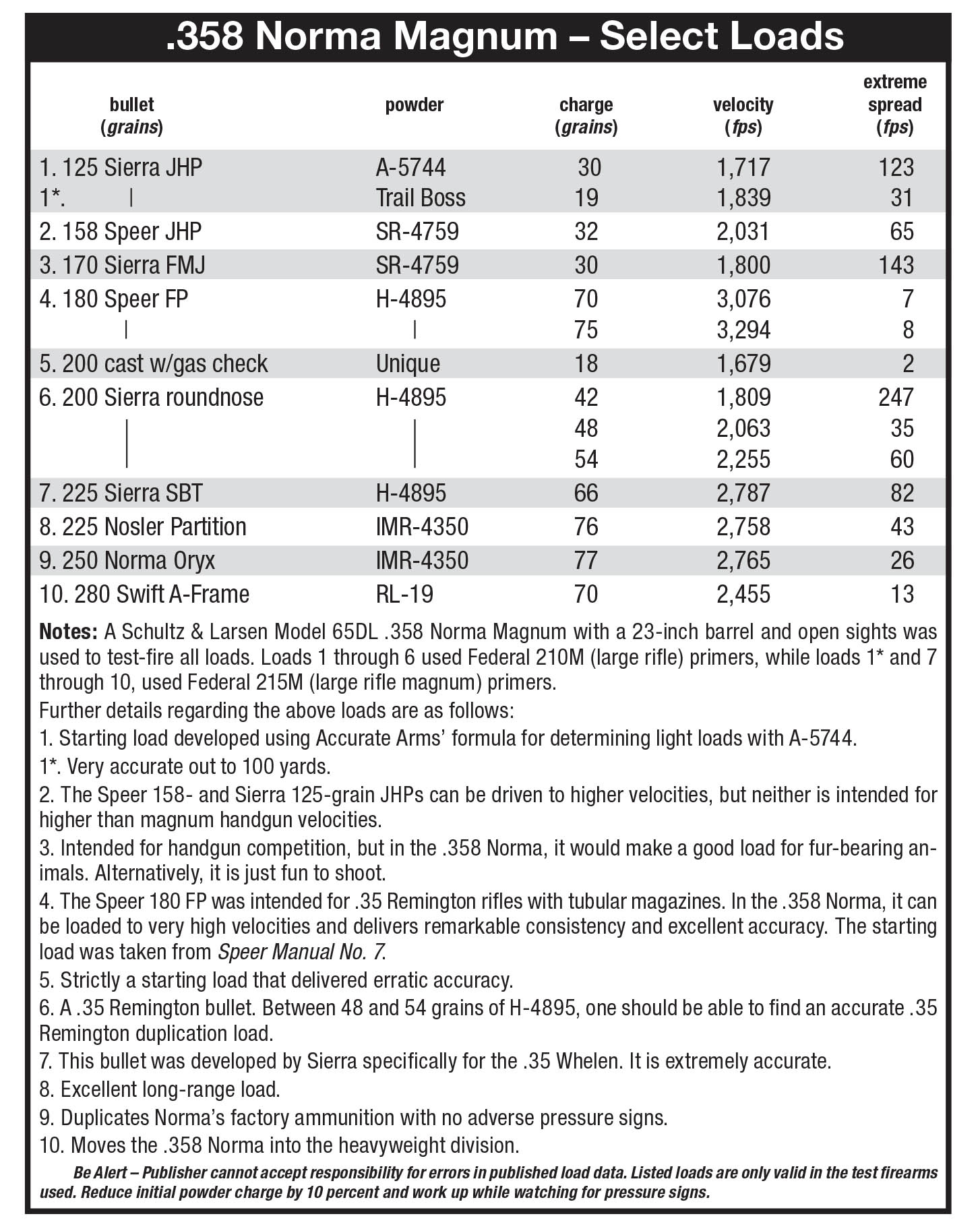

There are several reasons. First, it will do everything the .338 will, and a bit more. At the same time, it will do almost everything the .375 will but with vastly more versatility. For the handloader, as the accompanying table demonstrates, the .358 Norma Magnum provides an almost unbelievable range of possibilities, from loads light enough for gallery shooting to heavy enough

Unlike either the .338 or .375, the .35 (.358-inch) has been a standard American caliber since 1900. From the .35 Winchester (1903), .35 Remington (1906) and .351 Winchester Self-Loading (1907) to the later .358 Winchester (1955) and .350 Remington Magnum (1965), there has always been at least one .35-caliber cartridge in use. Griffin & Howe developed the semiwildcat .350 G&H based on the .375 H&H case, as well as pioneering the .35 Whelen.

The nearest of any to the .358 Norma was the .35 Newton, which it closely resembles. Throw a belt on the .35 Newton and you couldn’t tell the difference three feet away. The Newton was supposedly loaded, by Western Cartridge, to 2,975 fps with a 250-grain bullet, but I, for one, would want to see the chronograph reading. An earlier Western Cartridge load delivered 2,660 fps, which I suspect is closer to the truth. Either way, the Newton is the unbelted twin of the .358 Norma.

As a result of all this activity, .358-inch diameter jacketed rifle bullets are available in a wide range of weights and styles, from 150-grain semipointed to 200- grain roundnose, all the way up to 310 grains for the heaviest game. Not only that, many different bullet moulds were made for casting .358 bullets in some of the most fanciful shapes. Lyman lists 47 different moulds that were available at one time or another, ranging in bullet weight from 70 to 282 grains. Most were intended for .38-caliber handguns, but any bullet made for either the .38 Special or .357 Magnum can be loaded and shot in the .358 Norma Magnum with varying degrees of success. The better ones create mild gallery or small-game loads that are economical, quiet, virtually without recoil and – best of all – a lot of fun to shoot.

For anyone with an experimental or fanciful turn of mind, the .358 Norma and the many .358-inch diameter bullets are a gold mine. None of this can be said for either the .338 Winchester Magnum or the .375 H&H. In both cartridges, versatility is limited more by the narrow range of bullets available than by any other factor.

The first time I ever hunted with a .358 Norma Magnum, it was a custom rifle built on a Mauser Mark X action. I took it to Texas in 1989 and decked a nilgai at about 90 yards. The bullet went in behind the near shoulder, struck the far shoulder from the inside, and the blue bull hit the ground with a thud. It never got up. The guide professed to be dumbstruck: “I never saw a nilgai knocked down like that,” he said, “And we use some big rifles here!”

The bullet was the then-new Trophy Bonded 250-grain Bear Claw. As an experiment, I shot the nilgai five or six more times with different bullets, then hauled the carcass back to the cleaning station intact and carried out a necropsy. Of the bullets used, several performed extremely well, including the Bear Claw and a Nosler 250-grain Partition. The Norma factory load, with Norma’s own 250-grain bullet, performed poorly, coming apart in the chest cavity. It was recovered in bits and pieces. This was not the factory bullet from the 1960s, with its mild-steel jacket, but a later one. How it would have done on a live animal is impossible to say. Today’s Norma factory ammunition is loaded with the company’s excellent bonded-core 250-grain Oryx.

Among my own favorites for the .358 Norma are the Nosler Partitions in both 225 and 250 grains, Swift A-Frames (225, 250, 280) and various Woodleighs, including the unique 310-grain Weldcore. Any of these will handle just about any big game one might hunt with a .358 Norma, where you want to employ its ample knockdown power.

For more specialized uses, Speer makes a 180-grain flatpoint (semispitzer)that, with reduced loads, turns the .358 Norma Magnum into a pussycat for recoil but is easily capable of handling game such as black bears and white-tailed deer out to 250 yards or so. It can be the ballistic equivalent of the .30-06 with a 180-grain bullet or, pushed the other way, it can easily match the velocity of the .300 Weatherby Magnum with the same weight bullet. Sierra’s 225-grain spitzer boat-tail, designed for the .35 Whelen, is a stellar performer in the .358 Norma. As well, most bullet manufacturers produce soft, 200-grain roundnosed bullets intended for the .35 Remington, and these fit a wide range of uses.

With such a variety of bullets, you would think the sky’s the limit in terms of different loads, but there are other factors to consider. The major problem with light loads is getting enough pressure to provide a good gas seal. Powders such as IMR’s Trail Boss, Accurate’s 5744 and IMR’s discontinued SR-4759 all work with lighter bullets, and sometimes accuracy is very good, even if the gas seal is not. Since lack of a gas seal in a low-pressure load is more of a nuisance than a danger, it can be ignored if you don’t mind the soot.

With cast bullets, A-5744 and Trail Boss are usually the best choices, although H-4895 is a good powder for midvelocity hunting loads. Any listing you find for H-4895 can be modified by loading only 60 percent of the published minimum to create some very comfortable loads. From there, you can work up until you find a load that gives you the accuracy and velocity you want. The H-4895 load given in the table is not from any manual but was worked up with the assistance of Hodgdon ballistician Ron Reiber.

It’s safe to say that of all the .358 Norma Magnum rifles in existence, there are more custom than factory ones, and this makes it tricky to load for in another way. Original Schultz & Larsens had substantial freebore to keep pressures down, and Norma’s specifications for the cartridge called for it. That does not mean that any gunsmith who had his own ideas about velocity and accuracy might not include it or go completely the other way. For this reason, anyone acquiring a .358 Norma should start low with every load and work up slowly and carefully.

With such a wide range of both cast and jacketed bullets available, and today’s variety in powders, the .358 Norma has an embarrassment of riches when it comes to load possibilities. Short of a wounded elephant or Cape buffalo in thick cover, there is no game I can think of for which you could not concoct a load in the .358.

The original Schultz & Larsens were sold without iron sights, and they were installed on my rifle afterward. Frankly, I would not want to be without them. Being able to take off the scope and work with iron sights, using cast bullets or light jacketed bullets, adds an entirely new dimension to the rifle. In an age of ultra-specializatio in every field, and especially rifles, such versatility is almost an anachronism.

To return to our boxing analogy, the .358 Norma Magnum not only has the “Hammer of Thor,” but it also offers an excellent jab, a good hook, a wicked uppercut and a variety of feints. It can work in close or at a distance or dazzle you with footwork. Too bad Ingemar Johansson was not so well equipped. He, too, could have been one of the greats.