Deer Bullets for the .45-70

Loading the Lyman Gould's 45-330 Express Bullet

feature By: John Haviland | April, 17

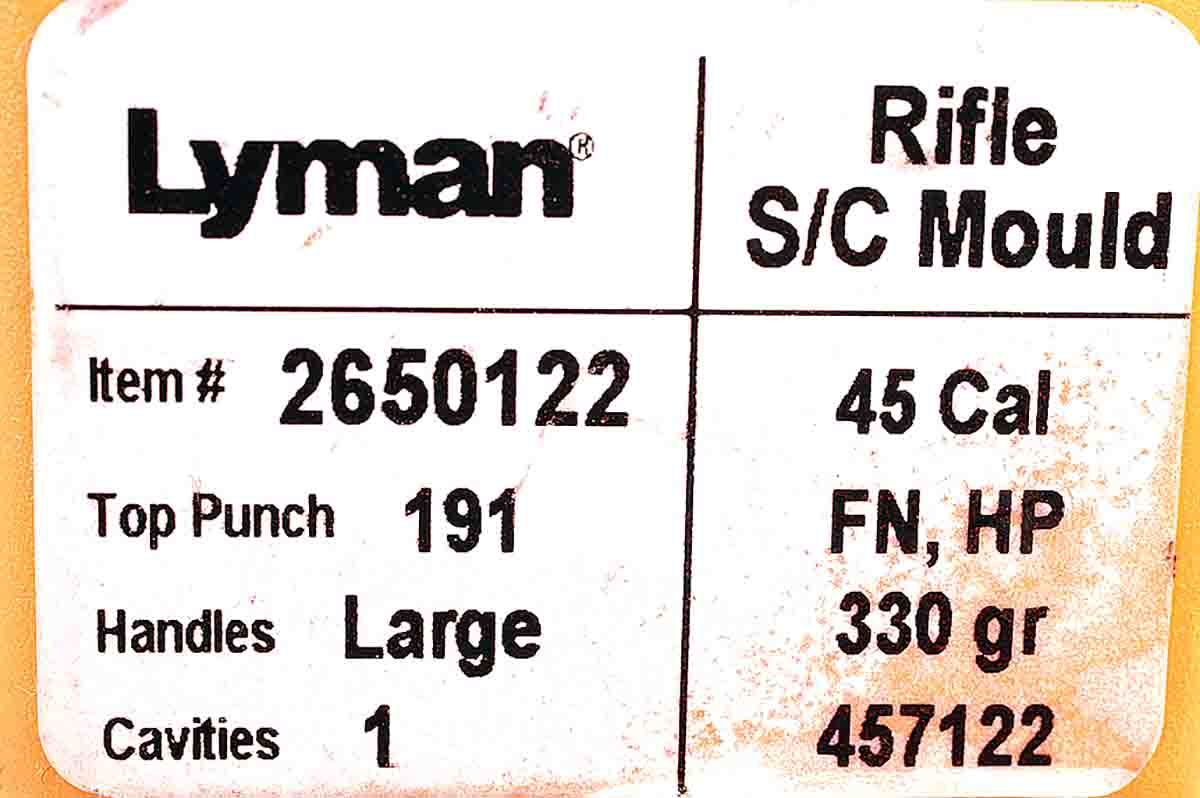

A few years ago my dilemma was solved by a cast bullet designed well over a century ago. Lyman sells its mould number 457122 for the bullet commonly known as the Gould’s 45-330 Express. A.C. Gould was the editor of Shooting and Fishing magazine in the late 1800s and set about to determine the best combination of bullet weight, velocity, trajectory, accuracy, manageable recoil and bullet expansion on game for the .45-70. In his book Modern American Rifles, published in 1892, Gould states:

I wrote the Ideal Manufacturing Co., of New Haven, Conn., to make me several moulds for bullets weighing 350, 330, and 300 grains, all with hollow points, and in due time received them. I found the tools were very carefully made, and the bullets, when cast, were apparently perfect. All of these bullets were tested in Winchester rifles, chambered for the .45-70 government

John Barlow, founder of Ideal Manufacturing, is credited with designing the Gould’s bullet. In his first Ideal Hand Book, Barlow states, “This bullet has given universal satisfaction as an accurate flyer and great killer of game. It has been used with equal success when shot from the various .45 calibre, 45-60, 45-70, 45-75, 45-85, 45-90 and 45-120.”

Only a few cycles of casting were required to bring the Lyman 457122 mould up to the proper temperature to create fully formed bullets. I slid out the hollowpoint pin, opened the mould and a bullet fell out of the mould. The Lyman Reloading Handbook 46th Edition (1982) and Lyman Cast Bullet Handbook (1999) lists a weight of 322 grains for the bullet cast of Lyman No. 2 lead alloy. However, the Lyman 50th Edition

The bullets could have been cast of a hard lead alloy, like Linotype, to better withstand higher pressure and velocity and produce better accuracy than wheelweight bullets, but the nose of the harder bullets might not expand on contact with game. If the Gould’s hollow nose did expand, the harder alloy would crack and break off, and only the shank of the bullet would remain. Wheelweight bullets are ductile, and as the hollow nose rolls back, it will remain attached to produce a wide diameter.

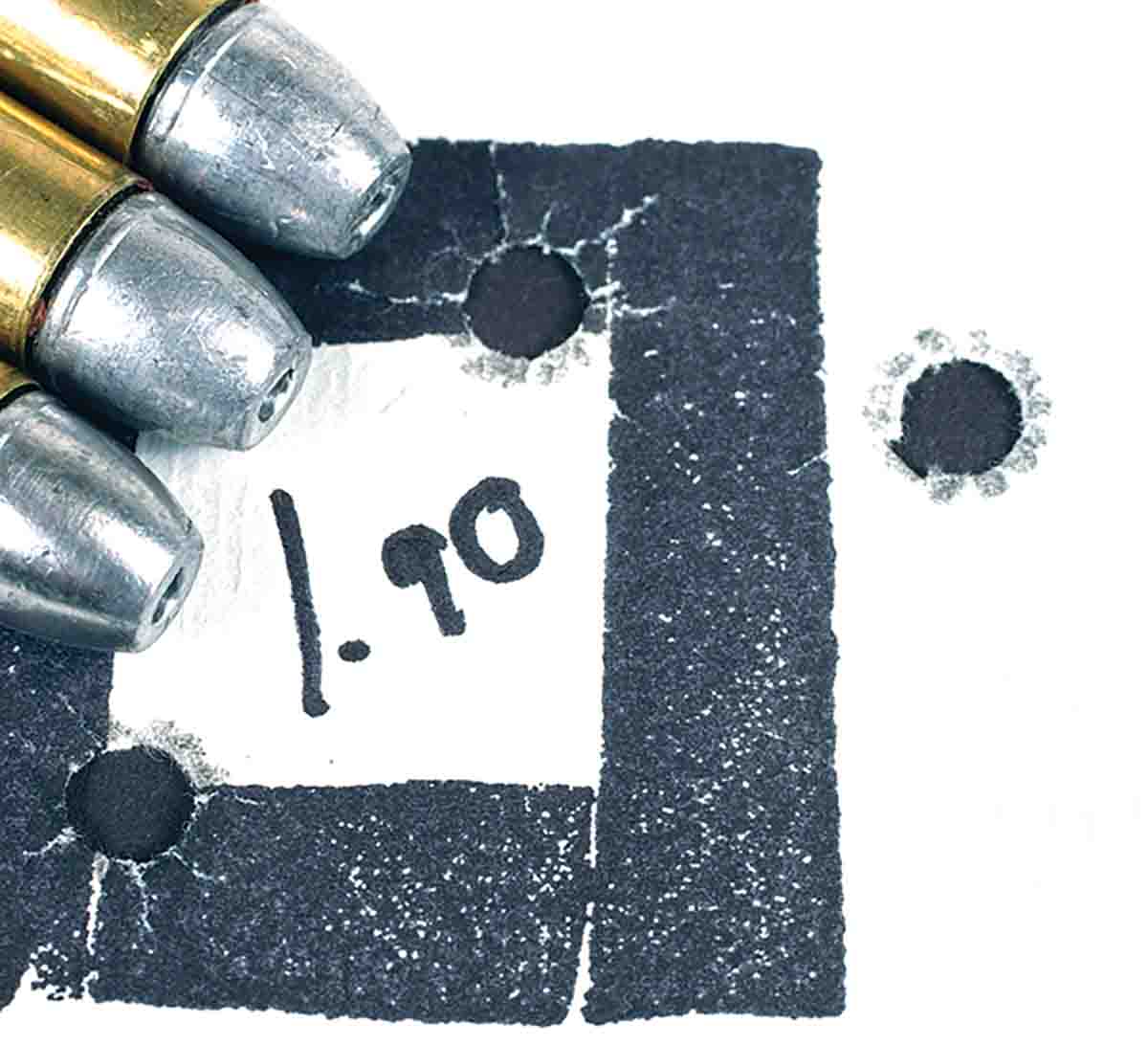

I fired wheelweight Gould’s bullets, with a striking velocity of 1,300 fps, into ballistic wax. The bullet’s deep, hollow nose really expanded, and recovered bullets were nearly mashed flat with a diameter of .622 inch. The bullets retained an average of 54 percent of their original weight. Penetration was relatively shallow at 7 inches, about half that of 407-grain flatnose bullets with an impact speed of 1,500 fps. The ballistic wax, however, is much denser than the ribs and lungs of a deer.

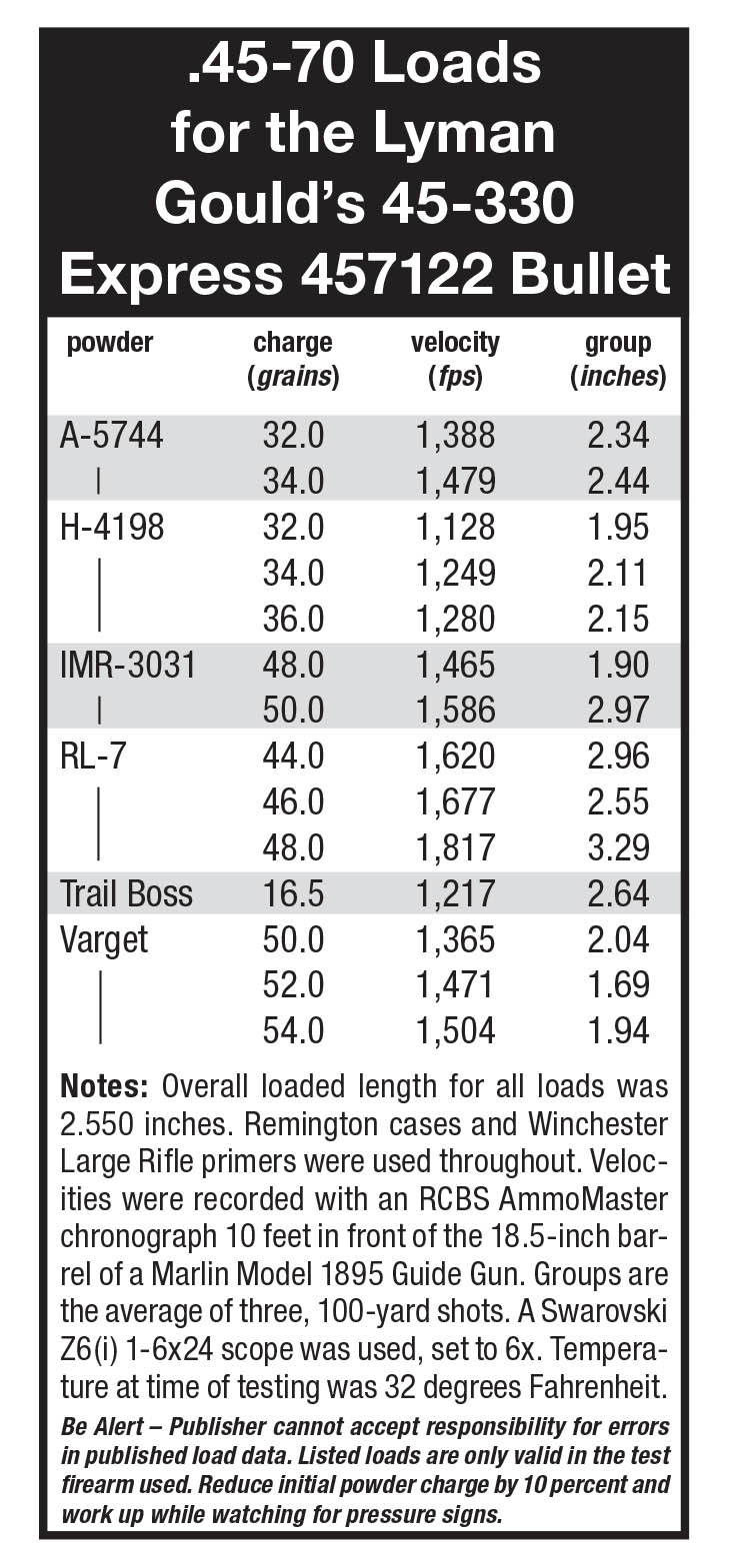

The next step was to find a level of pressure and velocity to produce acceptable accuracy and an adequately flat trajectory to

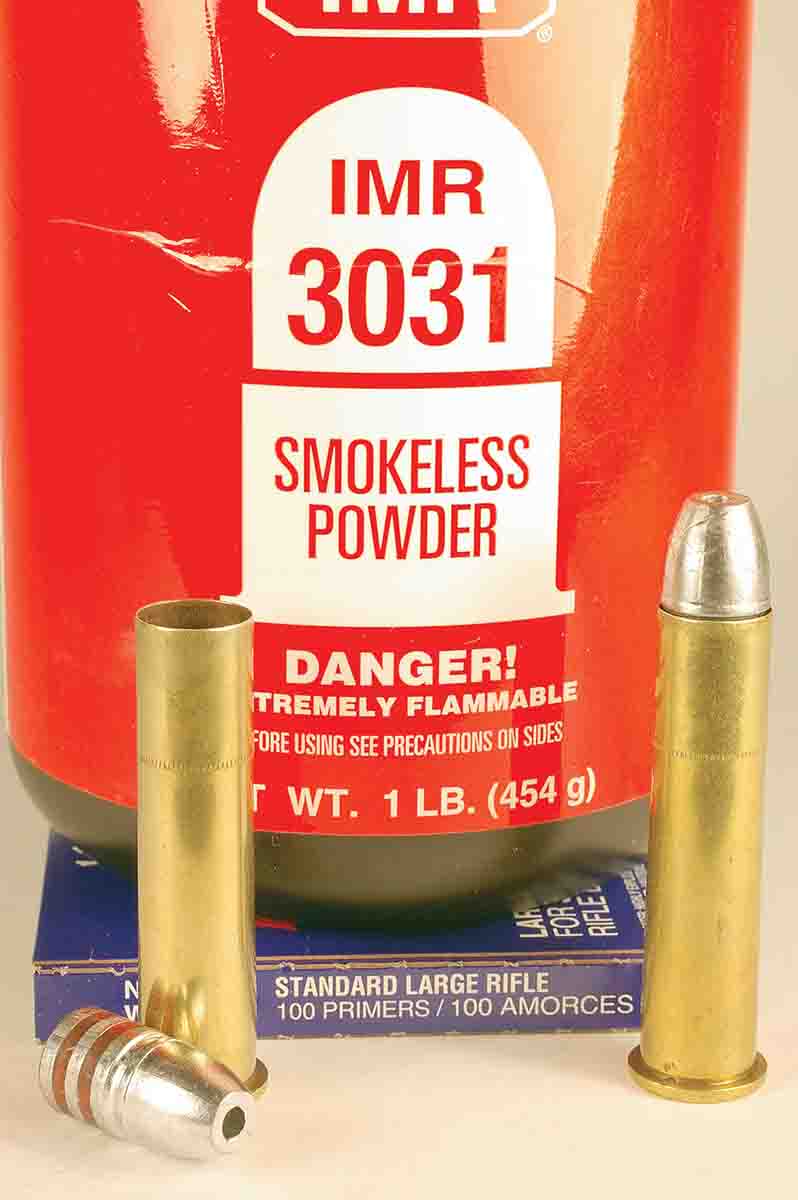

Preventing distortion of the plain base of the Gould’s bullet is an important step in attaining the best accuracy. Soft gas checks and case fillers were tried to protect the base of the bullets, but accuracy was poor compared to plain loads of the same powders. The Lyman handbooks fortunately list pressures with the various powders for the bullet. Choosing a powder that produces the desired velocity at a relatively low pressure should help avert deforming the base of the bullet. For example, the Lyman 50th Edition Re- loading Handbook lists the bullet’s velocity at 1,665 fps with 50.0 grains of IMR-3031 and 16,900 copper units of pressure (CUP). Conversely, about the same velocity was reached with 49.0 grains of H-322 at roughly 21,200 CUP.

I brushed the Marlin’s bore after shooting the loads with each powder. Patches pushed through the bore to wipe out fouling contained none to a very few flecks of lead. I looked into the Marlin’s bore with a Lyman borescope after shooting 10 bullets, some at over 1,800 fps. One spot at the start of the rifling had a slight wash of lead. The only other lead was two streaks on the lands near the muzzle.

Leading near the muzzle, according to the RCBS Cast Bullet Manual, “. . . appears to be consistent with alloy melting from frictional heat of high velocity. Remedial action is to decrease velocity or use a better grade lubricant.” So lead smears in the bore had nothing to do with the larger groups the Marlin rifle shot. Higher pressures that deformed the rather soft wheelweight bullets is what caused the wider groups.

For a deer hunting load, it was a toss up between 48.0 grains of IMR-3031 or 54.0 grains of Varget with the Gould’s bullet. I chose IMR-3031 for its even velocities. With a muzzle velocity of 1,465 fps, the bullet’s trajectory was 2 inches above aim at 50 yards, one inch high at 100 yards and 6 inches below aim at 150 yards. Recoil was a mild 15 foot-pounds in the 8-pound Marlin. That’s nearly one-third less than a .270 Winchester shooting 130-grain bullets from the same weight rifle.

I had a doe license in my pocket during the first season I hunted deer with the Marlin Guide Gun loaded with the Gould’s bullet. I peeked over a slight rise and saw a doe standing below about 50 yards away. The deer browsed along, facing away. I stepped over to a tree and leaned against it to steady myself and the rifle. When the deer turned slightly and showed its shoulder, I shot it behind the shoulder. The deer jumped at the shot and made a mad dash for 30 yards and fell over. Dressing the deer showed the bullet had hit at the rear of the lungs, plowed forward and exited the front of its far shoulder. The bullet had expanded well, with an entrance hole about the size of a 25¢ piece, and the exit hole was about the diameter of a 50¢ piece.

This past hunting season I sat on a stump for about an hour watching a timbered flat. A whitetail doe finally trotted out of a swamp, with a 10-point buck right behind it. The range was about 250 yards. If I had been carrying my .25-06 Remington, I could have taken a steady rest and shot the buck where it stood, but that shot for the .45-70 was too far.

The Gould’s 45-330 Express bullet had been easy and inexpensive to make and had expanded perfectly. The .45-70’s recoil had been mild enough that I watched through the scope as the buck fell. The bullet’s trajectory was a rainbow when compared to bullets shot from modern cartridges, and the shot required the close approach that keeps me enthusiastic about deer hunting.