Cartridge Board

The .410 3-Inch

column By: Gil Sengel | June, 20

Western Cartridge Company owners Franklin W. Olin and his sons John M. and Spencer T. soon discovered they were also owners of a new pump shotgun design specifically tailored for the 21⁄2-inch .410 shell. Begun in 1928 by Winchester engineer William Roemer, it was slated for production in 1932, but was now delayed for a very important reason.

A new long-range shotshell called SUPER-X from Western Cartridge Co. was gaining much attention among duck hunters. Western’s home in East Alton, Illinois, was on the great Mississippi River. This made such a shell quite logical. However, there was not yet such a thing as plastic shotshell components. Improvements had to come from paper wad design, harder shot and new progressive burning powders.

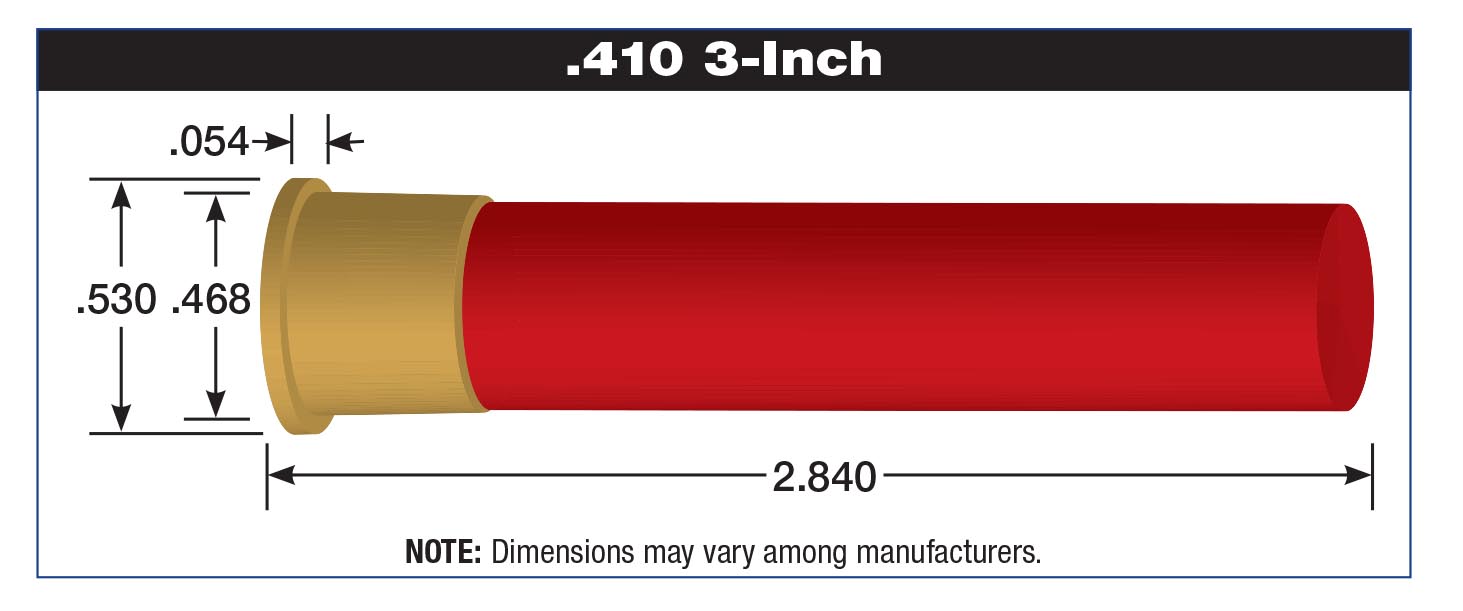

The chronicles tell us John M. Olin was an avid shotgunner who, along with some of his pals, thought the .410 should be improved for bird hunting. Thus Western Cartridge Co. lengthened the case to 3 inches, which upped the payload capacity to 3⁄4 ounce. Super-X technology was then applied to the round. It was announced in the 1934 edition of Western’s ammunition catalog. Shot sizes were numbers 4, 5, 6, 71⁄2, 8, 9 and 10. A 1⁄5-ounce roundball was also loaded.

The first mention of Winchester’s Model 42 for the 3-inch .410 was also in 1934. Marketing was different then. The gun and ammunition weren’t even called new until five pages into the description. The catalog then states, “. . . the gun with its new Winchester 3-inch Repeater Super Speed .410 gauge shell actually doubles the usual .410 gauge performance – a gun actually putting double the usual number of shot in a 20-inch circle at thirty yards – patterning more than the entire charge of other .410 gauge guns.” Exactly what did that mean? Why is there no mention of choke? Who knows, but it sounds good – I think!

Another gun was also available for the long .410 at this time. Iver Johnson produced a break-open single shot it called the Matted Rib Model starting in 1907. With the rib, excellent trigger, checkering and good stock dimensions, it was several cuts above any other single shot. It was immediately chambered for the 3-inch .410 and so advertised. The one I have kills doves every year, but the small effective pattern size leaves little room for error.

Even though the new round came out during the Great Depression, all makers of inexpensive, single-shot guns soon offered the longer chamber in their .410s. The reasoning was simple. Carrying a 3⁄4-ounce shot charge, the 3-inch .410 compared favorably to the standard 20-gauge load of 7⁄8 ounce – and a box of .410s cost ten to twenty cents less!

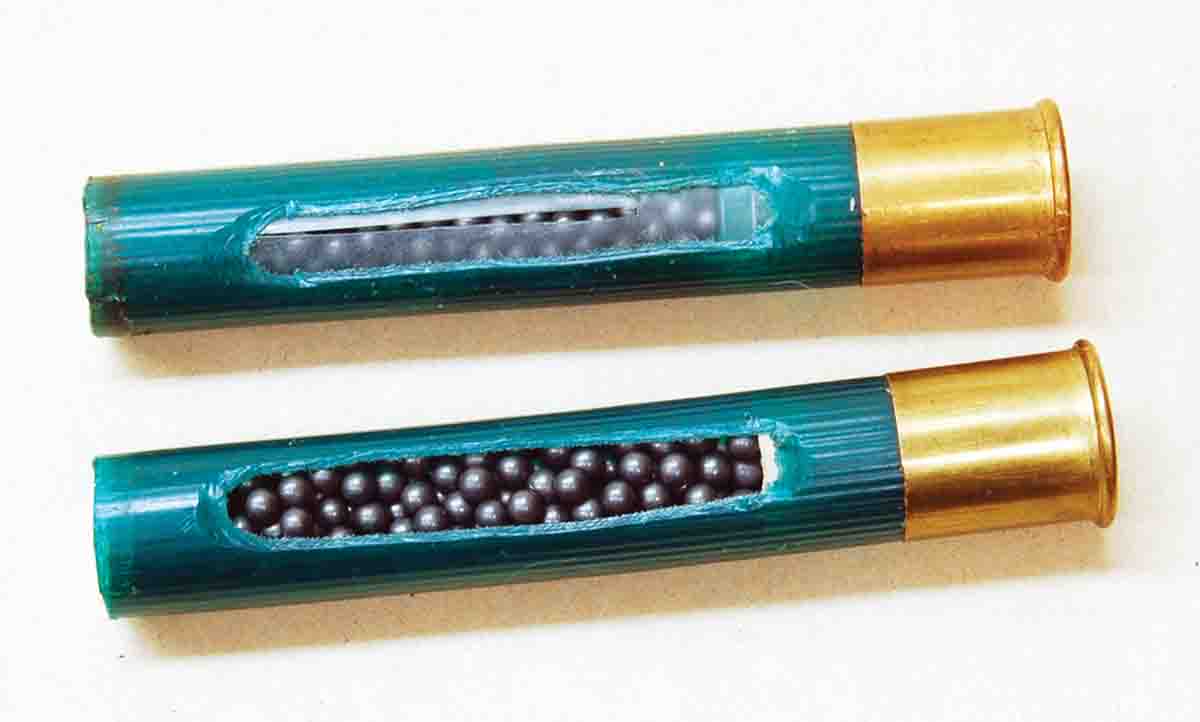

The great handicap of the long .410 is that for 30 years after introduction all shells had paper bodies, paper wads and a roll crimp. There were no cushion or filler wads, only a thin paper nitro wad over the charge of slow burning smokeless powder. Powder gas often escaped past the wad into the shot charge, fusing pellets together. Then the terribly long shot column rubbed against the narrow bore, damaging a large percentage of the shot, which then flew quickly wide of the main pattern. Dropping muzzle velocity could help, but it was already low at about 1,100 fps.

There was no change in the 3-inch .410 until the mid-1960s. Remington was first to replace the paper hull with plastic. A paper nitro wad and roll crimp remained. In 1972, the company announced the addition of a one-piece shotcup-type wad, but had to reduce the shot charge to 11⁄16 ounce to make room for it. Muzzle velocity was 1,135 fps. It is still available today in No. 4, 6 and 71⁄2 shot sizes along with one containing five No. 000 buckshot supposedly for self-defense.

Federal Cartridge Co. offered the 3⁄4-ounce load for years and even developed 3⁄8-ounce steel shot loads for the long .410 which are still available. A new load first listed in 2018 contains 13⁄16 ounce of No. 9 HEAVYWEIGHT TSS (Tungsten Super Shot). Pellets are 56 percent denser than lead. This load makes the 3-inch .410 into something totally unrecognizable – Federal illustrates it as a 40-yard turkey load. Unfortunately, cost is a major factor. Federal also lists two buckshot defense loads.

Western Cartridge Co. and Winchester likewise left the original cartridge unaltered until 1972, when its one-piece compression formed hull was adapted to the long .410. Some type of plastic shot protector (wad) must have also been employed, as the shot charge was dropped to 11⁄16 ounce. A load with five No. 000 buckshot came along in 2004. A steel shot round was developed and a 1⁄4-ounce rifled slug advertised at 1,800 fps appeared in the next few years. All are still listed today.

We now come to the obvious question of where the 3-inch .410 fits in today’s shotgunning. While the popularity of the .410 is stronger than ever, I can find no clay target competition that uses the long .410. Those buckshot loads for personal defense are a bit of a mystery. That leaves hunting. This is unfortunate because it is my experience that few owners pattern their .410s before taking them into the field.

Finally, no coverage of the 3-inch .410 is complete without mentioning the old quote, “The .410 is for beginners and experts only.” Personally, I wouldn’t let a new shooter anywhere near one. At least not for moving game. With excellent 3⁄4-ounce hunting loads available in 28 gauge and Claybuster’s 3⁄4-ounce wad for 20-gauge handloads, much better patterns are easily available than from the long .410. Handloaders can also vary 20- and 28-gauge velocities from about 1,125 fps to at least 1,250 fps. These gauges are available in the same single shots and youth model guns as the .410, so for beginners the choice is easy. That old quote is really only half true.

.jpg)