Tweaking Rifle Handloads

Details That Can Improve Accuracy

feature By: John Barsness | June, 20

Back then almost all hunting bullets were similar in construction, so-called cup-and-cores with a relatively thin gilding metal jacket swaged around a lead core. The first person I knew who handloaded Nosler Partitions – the only American-made controlled-expansion bullet then available – was a guy from “back East,” who came to Montana in the late 1960s as a hunting client of an outfitter I knew.

Most Montanans could not imagine paying that kind of money for either hunting or bullets. Resident deer and elk tags cost a buck apiece, and the .30-06 was the dominant “big” cartridge. It had worked fine for several generations with 180-grain cup-and-cores. This was also long before we realized slaying big game required sub-MOA accuracy, though some varmint hunters did prefer groups around an inch.

Apparently, many of today’s handloading hunters strive for sub-inch groups, and smaller is better, especially if we want to hold our heads up among our range buddies. One-inch groups can happen simply by trying different bullets, but today many hunters refuse to use whatever cup-and-core bullet shoots best. Today’s deer, whether white-tailed or mule-eared, apparently require controlled-expansion bullets capable of shooting lengthwise through a buck – and many hunters believe in only one specific brand. Many varmint shooters also prefer one brand, often with a plastic tip and a higher ballistic coefficient.

Such persnickety handloaders often refuse to try different bullets, though they are often willing to try several powders, partly because far more powders exist. When I started handloading at age 13, my Number 6 Speer Manual for Reloading Ammunition (1964) listed only eight powders for 180-grain bullets in the .30-06, half of which no self-respecting twenty-first-century handloader would consider. The Speer Handloading Manual Number 15 (2018), lists 20 powders for 180s.

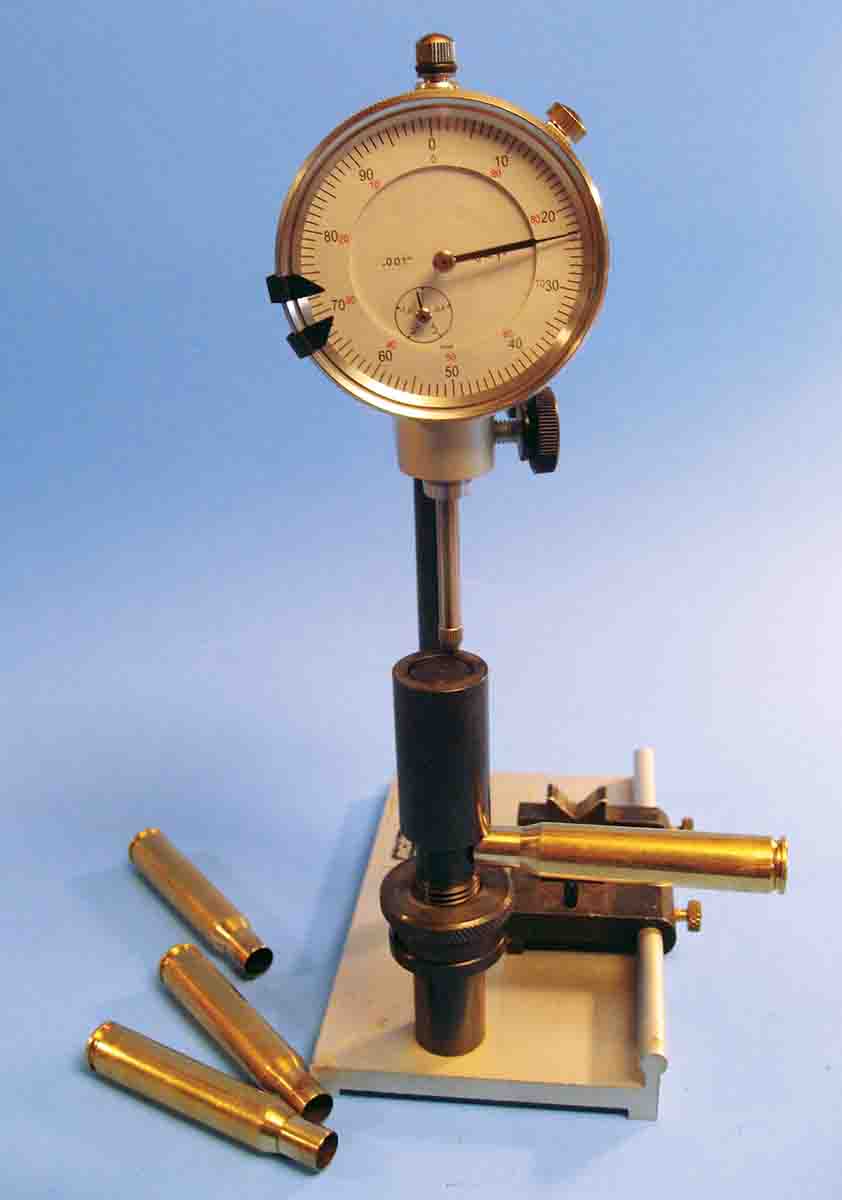

The primary problem with simply loading different bullets and powders and seeing how they shoot involves the first tweak, making sure the bullets are reasonably well aligned with the case. I cannot recall anybody mentioning this 50 years ago, whether locals or the “experts” writing for magazines subscribed to with paper route money, from American Rifleman to Outdoor Life.

There are various ways to reduce bullet runout, which can (and have) taken up entire magazine articles, including my “Rifle Die Design,” which appeared in Handloader No. 321 (August-September 2019). The main point, however, is checking and correcting runout is the first, basic step in tweaking rifle handloads.

Standard expander ball dies tend to pull the neck out of alignment with the case, but handloaders still may get lucky and end up with loads averaging an inch at 100 yards. However, even if the die works with cases having necks of very consistent thickness, they may not with a less precise brand of brass. Consistent neck thickness helps with any sort of sizing die.

A second often-mentioned accuracy tweak is neck sizing brass already fired in the same rifle. Supposedly, neck sizing positions each round precisely in the center of the chamber. Unfortunately, standard neck sizing dies use an expander ball, which tends to pull the neck even more out of line than full-length dies: The body section of the die is much larger than the case bodies, allowing cases to tilt more when pulled over the expander ball.

Fortunately, an inexpensive solution exists. Lee Collet neck sizing dies do not have an expander ball. Instead they use steel “fingers” to compress the neck around a mandrel/decapper of the correct diameter for holding seated bullets. This also reduces the need for sorting necks for consistent thickness.

The first Lee Collet die I ever used was for the .220 Swift, shortly after the collet dies appeared. The Swift was a Ruger No. 1B, and I had installed a Hicks Accurizer to stabilize the forend/barrel relationship. It shot pretty well, partly because I played with a full-length expander ball die to minimize neck misalignment, and used the die to only partially size the cases.

However, after hearing about the Lee die, I ordered one from MidwayUSA. After it arrived, I ran an experiment with the Ruger’s most accurate handload, using the standard die to load 15 rounds to fire three five-shot groups, and the Lee die to load another 15. You can see the results in Test 2.

Tests 3 and 4 involve changes in bullet seating depth. Most handloaders seat bullets close to the lands, having heard or read that is the most accurate seating depth. However, many of today’s bullets shoot best when seated a ways from the lands, at least in some rifles.

.jpg)

The two examples include the extremes found in my experimenting over the years. Test 3 uses my 6mm PPC benchrest rifle, which these days might almost be regarded as a “primitive weapon.” I bought it used in 2011, partly because it was built by well-known local gunsmith Arnold Erhardt, who has an excellent reputation for creating accurate rifles. It has a short Remington 700 action, stiffened by epoxying an aluminum “sleeve” around the receiver, a 25-inch Hart barrel and a “lay up” synthetic stock of unknown origin. (I asked Arnold, but he cannot remember the brand.)

The rifle was standing in the used rack at Capital Sports in Montana, with a price tag less than a quarter of a typical newly-built bench rifle. The very first five-shot group at 100 yards measured .37 inch, not close to competitive by today’s standards, but okay for starters.

The first experiments followed the traditional technique, trying various bullets and some popular 6mm PPC powders. The rifle did shoot better with a couple of custom bullets and the two most popular benchrest powders, Hodgdon H-322 and Vihtavuori N133. Instead it “liked” 65-grain Berger FB Target bullets and Hodgdon Benchmark.

The bullets were seated .03 inch off the lands, so I reduced seating depth, trying loads with the Bergers seated .02 inch from the lands, then touching the lands. The difference was dramatic, as the table shows.

The second test involved another customized Remington 700, originally a 7mm Short Action Ultra Magnum factory rifle. Kentucky gunsmith Charlie Sisk fitted a Bansner High-Tech synthetic stock, and fitted a No. 4 contour Lilja barrel chambered in 6.5 PRC, the Ruger Compact Magnum case necked down.

One slightly odd thing about the 6.5 PRC is the standard Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturer’s Institute (SAAMI) overall cartridge length of 2.95 inches, about .10 inch too long to fit in a typical short-action magazine, such as the 700’s. I decided not to fit a longer box until seeing how the rifle shot with bullets seated to fit in the magazine.

A charge of 60.5 grains of Hodgdon Retumbo produced the best accuracy with bullets around 130 grains. I retried the same charge with the bullets seated to an overall length of 2.860 – just short enough to fit into the 700 magazine, and almost .10 inch from the lands. This made no difference in accuracy with the other bullets, but groups with the 127-grain Barnes and 129-grain Nosler shrank considerably. I’ve shot the same handloads since then, and the average size of five-shot (not three-shot) groups is shown in the table. Both loads also shoot to about the same place at 100 yards, so can be used interchangeably.

Monolithic bullets such as the Barnes, and lead-cored bullets with very high ballistic coefficients, often shoot more accurately when seated further off the lands. Monolithics also tend to shoot well in Weatherby Magnums with long “freebore” throats, where bullets seated to fit in the magazine are always some distance from the lands. At least that has been my experience with several rifles chambered for various Weatherby Magnums, both factory and custom.

On the other hand, many flat-based lead-core bullets tend shoot best when seated close to the lands. However, this is just a general trend, the reason I always tweak seating depth if the old standby “close to the lands” does not shoot very well.

One handloading tweak I have yet to see make any measurable difference in typical factory hunting rifles, big game or varmint, is “uniforming” primer pockets, reaming them with one of the tools available from various manufacturers, and sometimes deburring the inside of the flash hole. For quite a while many handloaders have uniformed the pockets of all their cases – yet many of the same handloaders never bother to measure case neck thickness, which actually matters.

However, the specific primer can indeed make a measurable difference in accuracy. This is similarly ignored by many handloaders who never check neck thickness. In fact, many only use one brand and type of primer. For many years I was one of those guys, using CCI 200 Large Rifle or CCI 400 Small Rifle primers for all my rifle handloading, primarily because CCIs were always available in local stores. However, when the “Great Obama Shortages” occurred, I had to buy other primers – and of course test them to see if they worked as well. Sometimes they did not, but sometimes they worked better!

My tests indicate a specific primer usually makes the most difference in smaller cases, one reason I try several when handloading for rounds in the .22 Hornet to .223 Remington range. Primer choice tends to make the least difference in mid-capacity cartridges that work well with a wide variety of powders, such as the 6.5 Creedmoor and .308 Winchester. Cases from about .30-06 capacity upward often work better with magnum primers, particularly with spherical powders, where burn rate is controlled by powder coatings that delay burning to various degrees. Extruded powders, however, also use larger powder kernels to reduce burn rate, so it ignites more easily, and standard large rifle primers sometimes work best in the .30-06-sized rounds, and the short/fat magnums such as the .300 Winchester Short Magnum.

Test 5 shows the results from .17 Hornady Hornet and .22 Hornet handloads. In both rounds the CCI 450 Small Rifle Magnum primer resulted in the finest accuracy, though the difference was greater in the .17. This is contrary to common handloading wisdom, which suggests magnum primers are only required for larger powder charges.

Some people have also long used small pistol primers in the .22 Hornet, claiming better accuracy. That can be true with easily ignited extruded powders, but both the Accurate 1680 and Hodgdon Lil’Gun used in the pair of Hornets are spherical powders. In the thin Hornet case, they are also slower burning than suitable extruded powders, resulting in higher velocities at lower pressures, extending case life.

All of this is why I pretty much went straight to CCI 450s after buying a Brno .22 K-Hornet a few years ago – though I did try a couple of milder primers too, to compare to the 450 results. The powders included not just A-1680 and Lil’Gun, but Alliant Power Pro 300-MP, another spherical powder. (As the late Richard VanDenberg reported in Handloader No. 319, (April-May 2019) 300-MP is a slower-burning modification of Hodgdon H-110/Winchester 296.) Guess what? All three powders shot best with CCI 450 primers.

Often, however, somewhat larger cases, such as the 6mm PPC, group more accurately with extruded powders, the reason many benchrest shooters use either Federal 205 Match or CCI BR4 primers. Both are mild compared to CCI 450s.

However, once in a while even milder small rifle primers also work. When Western Powders introduced Accurate LT-32 a few years ago, I decided to try it in the 6mm PPC to see if a little more accuracy could be squeezed from my antique bench rifle. However, LT-32 did not shoot nearly as well as Benchmark with F205Ms, and not quite as well with CCI BR4s – but I had recently been playing with Sellier & Bellot primers made in the Czech Republic. Both S&B’s standard Large Rifle and Small Rifle primers had proven milder than most standard American primers, so I tried them with LT-32. Bingo! The average five-shot group shrank to .15 inch, slightly smaller than with Benchmark and F205Ms.

All of this tweaking may seem like a lot of trouble. It is, if you mostly handload for deer rifles never shot beyond 250 yards, but if you shoot at longer ranges, whether for deer or small varmints, or at steel gongs or simply shoot holes in paper, then tweaking certainly helps.