Frontier Ballistics

Tracing Traditional Loads

feature By: Mike Venturino | August, 19

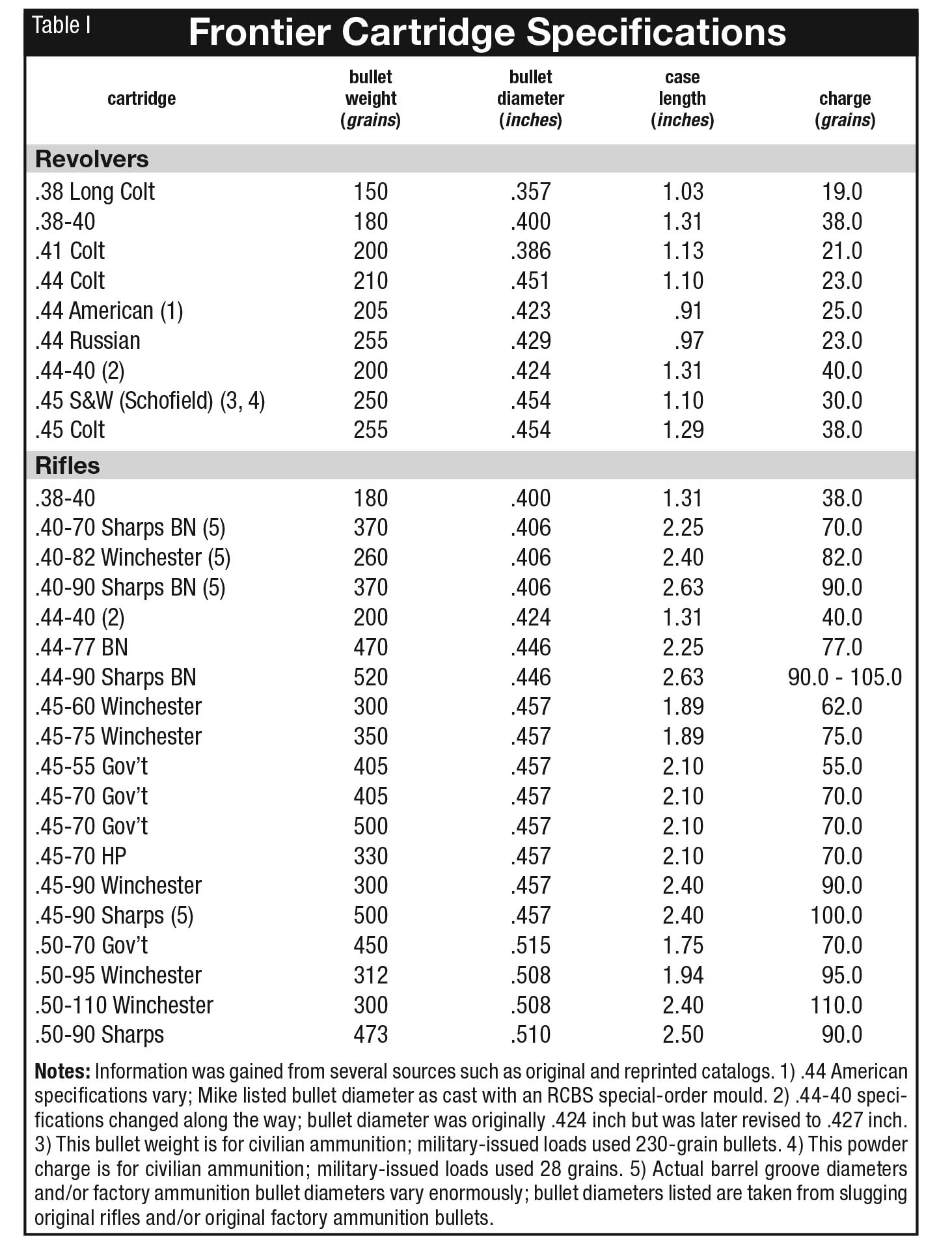

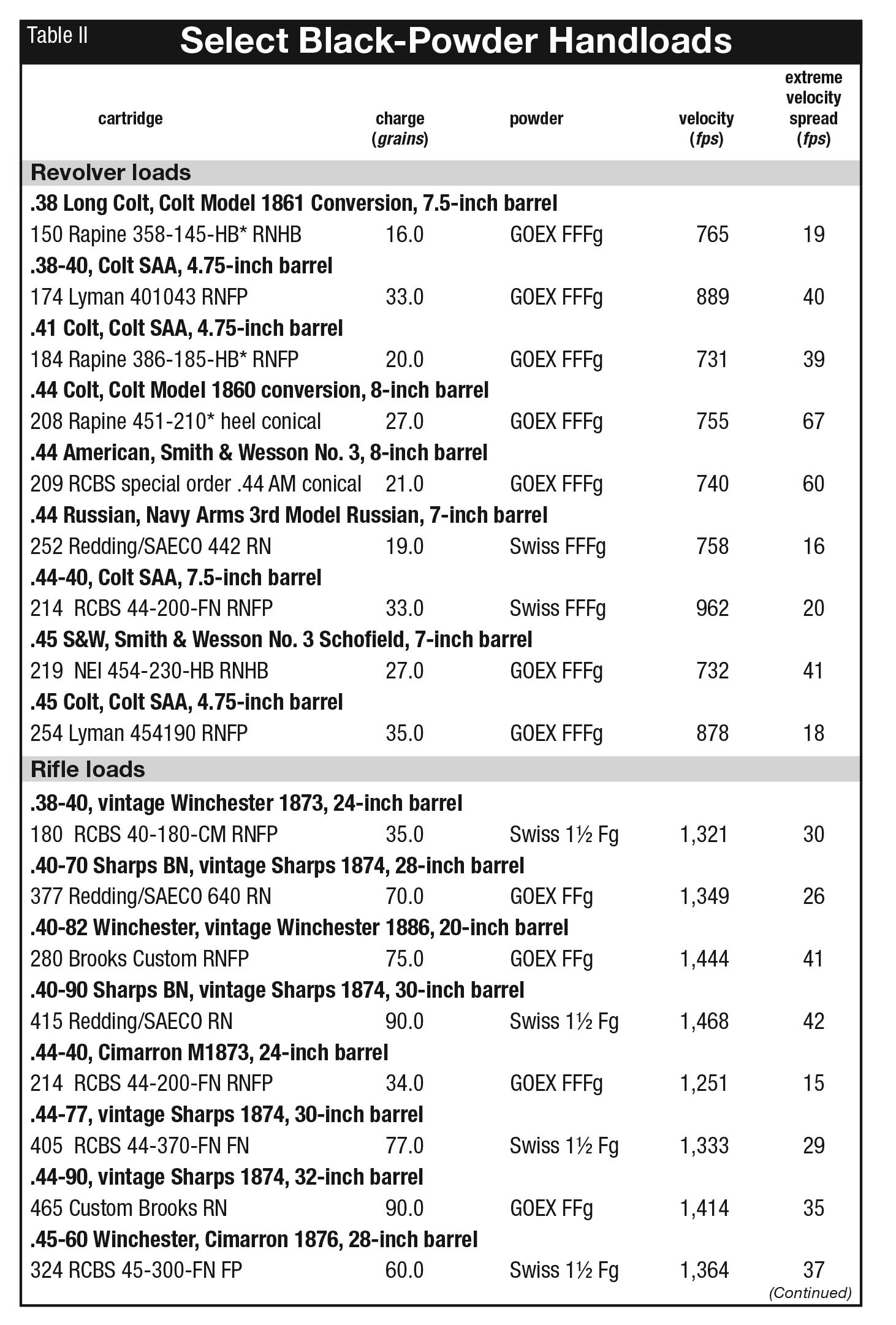

So, what was reality compared to make-believe? First let’s set some parameters for this article. I’ll start with metallic cartridge guns using black powder. That would have been the mid-1860s for rifles and 1870 for revolvers. Then I will quit circa 1890 before smokeless powders made their American appearance. By necessity, only centerfires will be covered; and by choice the sixguns that mostly rode in leather holsters unconcealed and rifles used for big game or combat. That quarter century saw so much use of black-powder metallic rifle and handgun cartridges that movies and books are still being produced about people from that era and the guns they used. Sometimes they are based on fact, and sometimes it’s legend.

Most early black powder metallic-cartridge guns were large, heavy sixguns, albeit weak in power. Here’s a brief summary of some examples: The .38 Colt, .41 Colt or .44 S&W American would not likely penetrate much wood because they didn’t push their soft lead bullets much in excess of 700 fps muzzle velocity.

Back in those early days of metallic cartridges, the only way to gain more power was to make bullets bigger and cartridge cases longer. As can be recognized in the accompanying tables, the earliest metallic revolver rounds used cases in the vicinity of one inch in length. When the truly powerful revolver rounds appeared, they used

Regarding rifle cartridges, I have separated them into two basic groups. One includes those that were also chambered in revolvers. There were four worthy of note: .44 Henry, .32-20, .38-40 and .44-40. The second set of digits in the last three denote their black-powder charge. The .32-20 and .44 Henry will be excluded here, the first being too mild according to my parameters, and the other due to its priming method. Winchester had a monopoly on repeating pistol cartridge leverguns from 1866 until Marlin introduced its Model 1889. In between, of course, was Winchester’s extremely popular Model 1873, of which about 750,000 were sold over a 50-year span.

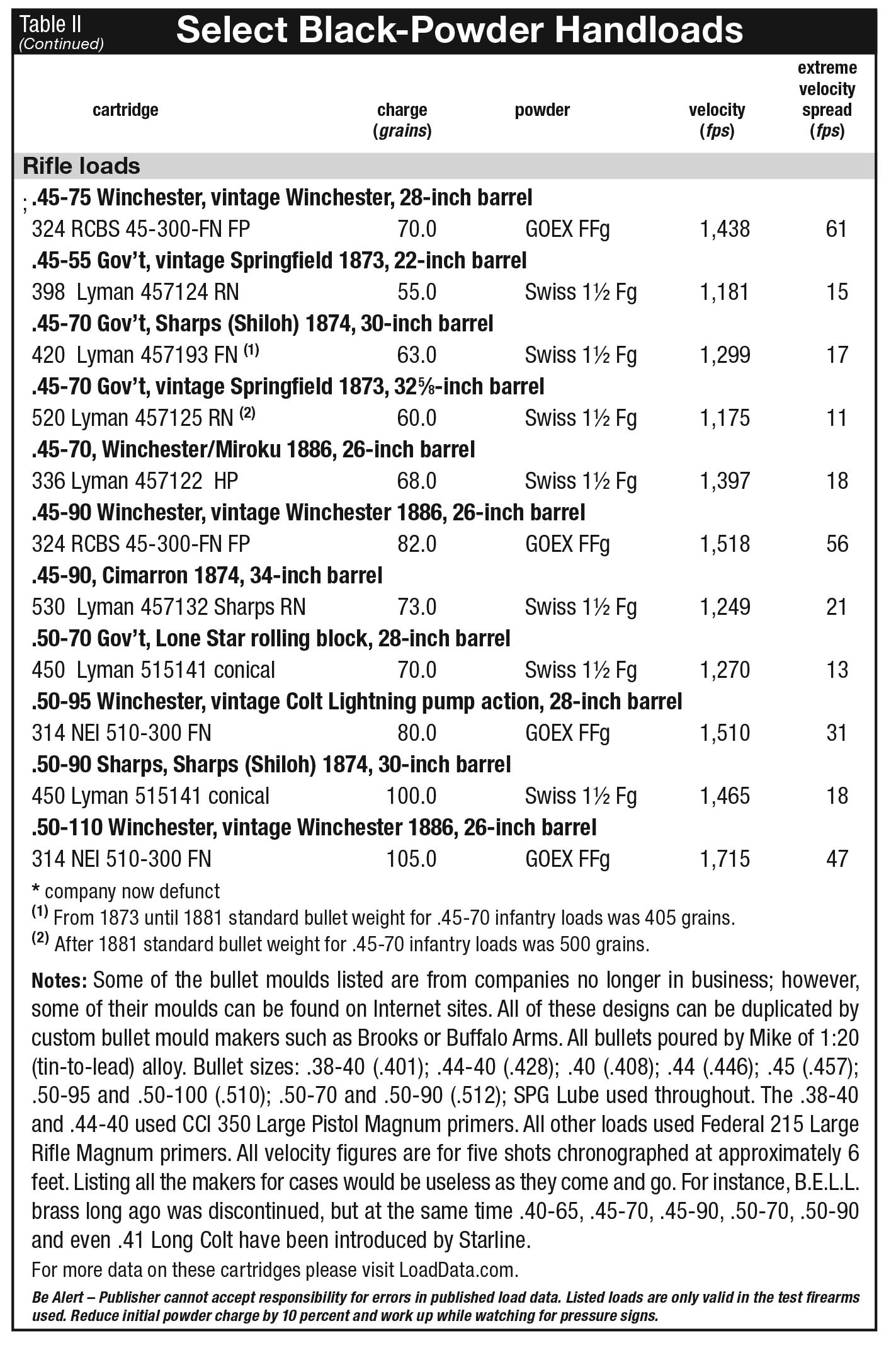

For the sake of simplicity, the following full-size rifle cartridges are noted by their modern colloquial names instead of those formally bestowed on them in the 1800s. Hence the .45 Government is the .45-70 and the .44 (2¼) Sharps BN is the .44-77, and so forth. This second group of rifle cartridges comprises so many that an entire volume would be needed to cover them all. So here the high points will be hit judging by popularity. First was the .50-70 in the Model 1866 developed by the U.S. government’s Springfield Armory. In several types of rifles and carbines, the .50-70 gained vast popularity “out west” with soldiers, Indians and buffalo hunters. Soon after the army adopted it, Remington chambered its No. 1 rolling blocks for this new centerfire cartridge. At this same time, the U.S. government was paying the Sharps factory to reline the barrels of its Models 1859 and 1863 percussion paper cartridge carbines from their original .52/.54 caliber to about .515 inch. They were then altered to centerfire from percussion ignition and chambered for .50-70. Then, in a strange move, those carbines were handed out to U.S. Cavalry troops and Indians alike.

The year 1873 was a banner one in firearms history, largely due to the .45-70. The cartridge was introduced in Springfield’s remodeled “trapdoor” Model 1873 infantry rifle and cavalry carbine. The carbine soon received a special load using only 55 grains of powder because troopers complained that the standard 70-grain charge’s recoil was excessive. After 1881 the army adopted a 500-grain bullet with a 70-grain powder charge for infantry use. The fact that .45-70 ammunition has been in constant manufacture since adoption while other “buffalo rounds” became extinct is testimony that the government did a fine job.

Winchester tried to rival the big single shots in 1876 with its new “Centennial Model.” Its first chambering was the .45-75, followed in the next few years by the .40-60, .45-60 and .50-95. Ten years later, the Model 1886 made its debut and pretty much put the ’76 Winchester out of business. New cartridges were introduced for the very strong ’86 until about 1903. The .40-82, .45-70, .45-90 and .50-110 will be covered here. The other six Model 1886 caliber options were either introduced too late to fit here, were not made in enough numbers to be significant or lacked power.

Shooting a mix of handguns at the baffle box was fun and interesting. First came a Kimber .40 S&W 1911 and a Les Baer .45 Auto 1911. Each of their FMJ bullets made it through eight planks. Board No. 6 was popular: .38-40, .44 Russian and .45 S&W pressed through it. The .38-40 was a bit of a disappointment. I expected it to equal or better .44-40 penetration, but in fairness I must say that the .38-40 bullet exited a 4.75-inch SAA barrel while the .44-40’s was shot from a 7.5-inch barrel. A surprise was the .44 American bullet, which planted itself in the seventh plank. I expect that slight bit of improvement was due to its pointed bullet and the fact that it was fired from an original Smith & Wesson No. 3 with an 8-inch barrel. The ninth plank had only two holes through it, one of which was from the flatnose .44-40 bullet. With no surprise, the best penetration of all was with the .45 Colt. Its 252-grain conical bullet lodged in the twelfth board. Its performance was also probably aided by the pointed nose shape plus being fired from a 7.5-inch Colt SAA.

Here are some details for this “frontier ballistic” testing, which extended over several years. Tens of thousands of rounds have been fired in a huge variety of original and replica firearms. Many were mine, and some were loaners from friends. If I could not get them to shoot with at least adequate accuracy, they were not included in the table.

Some components were used for all the black-powder handloads shown here. Primers were always CCI magnum strength for both small and large pistol loads. Most of the full-size rifle cartridges were primed with Federal 215 Large Rifle Magnum primers. Only SPG lube was used on cast bullets, which were all poured of 1:20 (tin-to-lead) alloy.

The 1870s especially, and the 1880s to a lesser extent, were the great trial years of metallic cartridges. The U.S. government and both large and small ammunition factories constantly experimented and tested new ideas. Even the Russians “colluded” in 1872 by insisting the .44s sold to them by Smith & Wesson used a bullet the full diameter of which set inside the case. Prior to that, most factory handgun loads featured heel-type bullets with a reduced diameter shank that fit inside the cartridge case while the full bullet diameter was same as the outside case diameter. By about 1890 most heel-type bullet factory ammunition was dropped in favor of the Russian method. Hence the .41 Colt ended up being loaded with .386-inch hollowbase bullets, and the .38 Colt ended up with .357 diameter hollowbase bullets. Those cartridges shot very well with those soft lead-alloy hollowbase bullets – expanding .014 to .016 inch to grip rifling. As said, it was a time of experiments and learning.